Category: Education

The power of “because”

Behavioral scientist Ellen Langer and her colleagues decided to put the persuasive power of this word to the test. In one study, Langer arranged for a stranger to approach someone waiting in line to use a photocopier and simply ask, "Excuse me, I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine?" Faced with the direct request to cut ahead in this line, 60 percent of the people were willing to agree to allow the stranger to go ahead of them. However, when the stranger made the request with a reason ("May I use the Xerox machine, because I’m in a rush?"), almost everyone (94 percent) complied…

Here’s where the study gets really interesting…This time, the stranger also used the word because but followed it with a completely meaningless reason. Specifically, the stranger said "May I use the Xerox machine, because I have to make copies?"

The rate of compliance was 93 percent.

That is from Bob Cialdini’s Yes! 50 Scientifically Proven Ways to be Persuasive; here is my previous post on the book. And here is why motivational posters don’t work.

The Price of Everything

Here is Ezra Pound’s Usura Canto, here is a link to Russell Roberts’s The Price of Everything: A Parable of Possibility and Prosperity, available for pre-order. Can you guess which one has the better economics? In fact Russ’s book is the best attempt to teach economics through fiction that the world has seen to date.

Here is Russ’s summary of the book. Here is Arnold Kling on the book.

The one hundred item challenge

Could you live with no more than one hundred possessions? A group of Americans have accepted this challenge. I found this passage insightful:

Walsh isn’t surprised that decluttering is so popular these days.

Between worrying about gas prices and the faltering economy, people’s

first reaction, he says, "is often, ‘I need to get some control over my

life, even if it is just a tidy kitchen counter.’"

And of course there are cheaters:

One of the trickier questions is what counts as an item. Bruno

considers a pair of shoes to be a single entity, which seems sensible

but still pretty hard-core when you’re trying to jettison all but 100

personal possessions. Cait Simmons, 27, a waitress in Chicago, takes a

different approach. Although she has pared down her footwear collection

from 35 to 20 pairs, she says, "All my shoes count as one item."

The pointer is to Jason Kottke.

The decay of gratitude

[Francis] Flynn asserts that immediately after one person performs a favor for another, the recipient of the favor places more value on the favor than does the favor-doer. However, as time passes, the value of the favor decreases in the recipient’s eyes, whereas for the favor-doer, it actually increases. Although there are several potential reasons for this discrepancy, one possibility is that, as time goes by, the memory of the favor-doing event gets distorted, and since people have the desire to see themselves in the best possible light, receivers may think they didn’t need all that much help at the time, while givers may think they really went out of their way for the receiver.

That is from Robert B. Cialdini’s fascinating Yes! 50 Scientifically Proven Ways to be Persuasive. Cialdini’s earlier Influence remains one of my favorite social science books. Here is a link to Flynn’s paper and related work.

Teaching

Roland, a loyal MR reader, sends me this quotation from Max Weber:

The primary task of a useful teacher is to teach his students to recognize ‘inconvenient’ facts – I mean facts that are inconvenient for their party opinions. And for every party opinion there are facts that are extremely inconvenient, for my own opinion no less than for others. I believe the teacher accomplishes more than a mere intellectual task if he compels his audience to accustom itself to the existence of such facts. I would be so immodest as even to apply the expression ‘moral achievement’, though perhaps that may sound too grandiose for something that should go without saying.

How long should you wait for an elevator?

Jason, a loyal MR reader, asks:

Google wasn’t able to help me here.

I figure that the longer you wait, the shorter the expected remaining waiting time.

However, in the worse case, if the lift has broken down, the waiting time could be infinite.

For an individual lift, one could, I suppose, collect some stats on average wait times, but I’m interested in the best strategy for an arbitrary lift.

The technical approach is to model the arrival of the elevator as a mathematical process, set up the problem, and solve it. The seat of the pants approach is to ask about your psychological biases. Are you, in the first place, more likely to spend too much or too little time waiting for elevators? In my view standing and waiting isn’t so bad, provided you have something to do or think about. So my advice is this: once you start waiting for an elevator, begin to think through some interesting problem you face. The ideal is that when the elevator arrives, you will be disappointed and of course that means you have hedged your risk in the first place. The question that people screw up is not how long they should wait but what they should do in the meantime.

If you’ve finished thinking about your problem and the elevator still isn’t there, take the stairs.

Readers, what do you advise? Is there a second best case to be made for "elevator waiting indecisiveness," or should you just have a simple time rule and stick with it? Is there a formula based upon the number of shafts and number of floors in the building? The frustrated look of the person standing next to you?

Should Harvard continue to accumulate an endowment?

Matt writes:

A university that rich [Harvard] ought to either embark on some kind of ambitious

expansion program and start educating substantially more students, or

else decide that it would unduly alter the character of the place to

expand that much and just close up the development department and enjoy

the luxury of being able to focus single-mindedly on the university’s

core teaching and research functions.

Taking this as personal advice, I agree: don’t donate your money to Harvard. But as a matter of public policy I would not disturb the current arrangement. First, a donation to Harvard is an act of conspicuous consumption by the rich, a bit like buying the watch that doesn’t tell time. In other words, the donors benefit, either through a warm glow or perhaps they receive networking opportunities. Like Bob Frank, you might think we need a new consumption tax on the rich (not my view) but even if so we shouldn’t single out Harvard as a starting target.

Second, the Harvard endowment earns a high rate of return, relative to the cost of raising the funds. Let’s say the fund nets 10 percent a year. There is some trickle down and furthermore even if you wish to confiscate those resources it is always better to do so later rather than sooner. The wise guy point here is to suggest that everyone give all their money to Harvard and arrange for some ex post compensating transfer. (I’ve heard by the way that Yale faculty sometimes demand that Yale money managers take care of their personal portfolios.) Obviously that’s not realistic but the point remains that ten percent is a very good return on investment. Let’s say Harvard earned forty percent a year: should this make us more or less likely to leave the current arrangement in place?

Public vs. private schools

No, this is not a policy question. Rather Jenny, a loyal MR reader, asks for advice:

As an economist, I was wondering if you could provide any insights to us parents evaluating public versus private elementary schools for our kids…By comparison [with the good private school], my public school education seems shoddy. But at $21,000 for kindergarten and a younger sister that would be joining him, this is a huge financial commitment, and takes away our flexibility to do anything but grind away for the next 15 years. My son is bright and curious – how do I know that he will get that much of an incremental improvement being in private school? And despite my very non-inspiring, and at times dreadful, public education, I can’t say that I’m any worse off for it today…I’ve been really struggling with how to evaluate this. Can economics shed any light?

I faced this same choice myself as a kid and I ended up telling my mother I was happy to remain in the public school. If nothing else I feared the commuting costs and not having friends’ homes be nearby. Furthermore at public school I met Randall Kroszner and Daniel Klein, among other notables. Natasha and I faced this choice again with Yana and she ended up in public high school. I can’t really cite economics here but if your public school is halfway decent that is the side I come down on.

Readers?

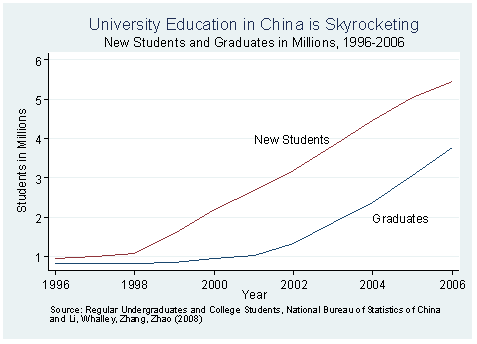

The Education Transformation of China

University education in China is skyrocketing. In 1996 China had less than 1 million freshmen, in 2006 there were over 5 million freshmen. The freshman class is continuing to grow and university graduates, of course, are just 4 years behind. About half of the entering students are in a hard science or engineering program. As a result, China today produces 3 times more engineers than the United States and will quickly overtake the U.S. in total graduates.

Many people worry about what the Chinese education explosion means for

the United States but I am optimistic. First, as China and other countries grow wealthy the

incentive to invest in R&D is increasing. If China and India were as wealthy as the U.S. the market for cancer drugs, for example, would be eight times larger than it is today – and a larger market means more new drugs for everyone.

Second, the growth in Chinese education is

increasing the supply of new ideas and that too is a benefit to people around the world.

Surprisingly, China’s education system is being

transformed to a

considerable degree by private forces. As late as 1999 the Chinese government

paid for most university education but from 2001 onwards tuition and

fees account for more than half of total educational expenditures.

I have drawn much of the data in this post from a fascinating new paper, The Higher Educational Transformation of China and its Global Implications by Li, Whalley, Zhang and Zhao. The paper has much else of interest.

I will be traveling to China to give a talk at Yunnan University in late June and will report on the transformation as it looks on the ground.

How to read a vita

Ugo, a loyal MR reader, asks:

If you were in a tenure committee how

would you evaluate an assistant professor who, among other things, has

two papers in a top journal with the second paper showing that the result

of his/her previous paper is wrong.(a) Consider this situation has having

two publications in a top journal (the rationale for this is that you want

to give incentives to seek the truth and the two papers contributed to

our understanding of the problem, moreover the author showed to be able

to publish in top JNLs)(b) Consider this situation as having

one publication in a top journal (same as above, but you recognize that

the contribution is less than two papers with a true result).(c) Give zero value to the two papers

(because the results cancel each other).(d) Give negative value to the two papers

(because people wasted time on a wrong result).

The best way to read a vita is to think of it in terms of a portfolio. If all a person had on his vita was a single paper and then its repudiation, I would not think much of the combination. If the person is producing a stream of papers, as a whole pointing toward greater knowledge and fleshing out a coherent research program, I would view the revisions and repudiations as a sign of intellectual strength.

Most questions about how to read vitas can be clarified by this portfolio approach. For instance I am often asked how much a piece in Journal X is worth. The correct response is to ask whether that publication complements a broader research program or not and then to ask how valuable that research program will be.

Not From the Onion

FTC Wants to Know What Big Brother Knows About You

That’s the headline for a story in today’s Washington Post (about government regulation of internet advertising). I suspect the irony was lost on the editors or perhaps this is an Orwellian attempt to twist language.

Addendum: The irony was not lost on the ever-wise Arnold Kling.

Measuring Up

The subtitle of this excellent book, by Daniel Koretz, is What Educational Testing Really Tells Us. Here is one excerpt:

The distressingly large achievement differences among racial/ethnic groups and socioeconomic groups in the United States lead many people to assume that American students must vary more in educational performance than others. Some observers have even said that the horse race — simple comparisons of mean scores among countries — is misleading for this reason. The international studies address this question, albeit with one caveat: the estimation of variability in the international surveys is much weaker than the estimation of averages.

…We are limited to more general conclusions, along the lines of "the standard deviations in the United States and Japan are quite similar." Which they are. In fact, the variability of student performance is fairly similar across most countries, regardless of size, culture, economic development, and average student performance.

I was shocked to read this but the book is highly reputable and persuasive.

Economicwoman.com

That is the site address for a new blog on feminism and economics. Allison, the blogger, points us to a YouTube channel on feminist economics.

Here is Allison’s advice for economics undergraduates; feel free to add to it in our comments section.

I loved this question, and answer

Question for the day: what do libertarianism and the Many-Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics have in common? Interest in the two worldviews seems to be positively correlated: think of quantum computing pioneer David Deutsch, or several prominent posters over at Overcoming Bias, or … oh, alright, my sample size is admittedly pretty small.

…My own hypothesis has to do with bullet-dodgers versus bullet-swallowers.

And it ends with this:

So who’s right: the bullet-swallowing libertarian Many-Worlders, or the bullet-dodging intellectual kibitzers? Well, that depends on whether the function is sin(x) or log(x).

Read more here and can you guess who the pointer is from?

The Storm

The storm ravaged the city’s architecture and infrastructure, took

hundreds of lives, exiled hundreds of thousands of residents. But it

also destroyed, or enabled the destruction of, the city’s public-school

system–an outcome many New Orleanians saw as deliverance….The floodwaters, so the talk went, had washed this befouled slate

clean–had offered, in a state official’s words, a “once-in-a-lifetime

opportunity to reinvent public education.” In due course, that

opportunity was taken:…Stripped of

most of its domain and financing, the Orleans Parish School Board fired

all 7,500 of its teachers and support staff, effectively breaking the

teachers’ union. And the Bush administration stepped in with millions

of dollars for the expansion of charter schools–publicly financed but

independently run schools that answer to their own boards. The result

was the fastest makeover of an urban school system in American history.

That’s from The Atlantic just over a year ago. Guess what? It’s working. The storm is coming.