Category: Medicine

Sentences to ponder (there is a great stagnation)

Over the span of our data, health IT inputs increased by more than 210% and contributed about 6% to the increase in value-added. Virtually all the increase in value-added is attributable to the increased use of inputs…

Here is much more. Can anyone find an ungated copy?

Amy Finkelstein wins the John Bates Clark award

Sorry to be late on this one, but here is the AEA take on her contributions, many of which involve health care economics and the study of health insurance. I am not sure she was considered an obvious front-runner from the beginning, but in my view it is an excellent pick (without intending any slight to the billions who were passed over). She is trying to understand the real world, and she is showing that policy economics should not have lower status in academia. Obviously her major areas of study are topical today.

She does, by the way, have several previous mentions on MR and in retrospect she should have more. Sarah Kliff adds a bit more.

Relative to baseline forecasts, ACA and otherwise

Ruritania is fighting a war, and the status quo setting is that 90,000 lives will be lost each year. General Blythe comes up with a plan that increases the chance of winning the war, but is likely to cost 120,000 lives a year. He claims his plan costs only 30,000 lives a year, relative to baseline. General Smythe has a war plan which on net costs only 80,000 lives a year, so he argues that his plan saves 10,000 lives a year.

In comparative terms these claims are not incorrect, and there are obvious reasons why bureaucracies should draw up such estimates. Yet an anti-war group, SDS, argues that the real cost of the war is 90,000 lives each year, and that the one alternative plan costs 120,000 lives a year and the other 80,000 lives a year. If you are rethinking the entire war, the SDS estimates are relevant.

If we are going to keep at the war no matter what, the estimates of the Generals may be more useful. In the meantime, the generals get upset that SDS is stepping out of the framework of policy discourse and refusing to offer or accept numbers “relative to baseline.” Discourse fractures and names are flung.

To translate that into 2012, the “war” is the joint view — extremely common in America — that a) tax revenues are on an acceptable track, and b) we should spend more and more on health care each year at high rates, including in per capita terms.

If you think that dual project is sustainable, you may be relatively interested in estimates relative to baseline. If, like me, you think that project is like a failed and failing war, a success “relative to baseline” won’t much impress you. In fact it may scare you all the more to hear about success relative to baseline, as that can be taken as a signal that there is no really good plan behind the scenes. Here are a few factors which could radically upset current mainstream baselines:

1. Rates of growth stay in the range of 1 to 1.5 percent, see the work of Stock and Watson, top macro econometricians. Try redoing budget projections with those numbers.

2. Real rates of growth are higher than that, but they take the form of non-taxable pecuniary benefits.

3. Growth rates are acceptable, but more and more of economic growth is captured by private capital, which is difficult to tax for either mobility or political economy reasons.

4. The United States may need to fight a major war, or prepare to do so. (I do favor cutting the defense budget now, but we can’t be sure that cuts can last.)

5. The political economy of revenue hikes and/or spending cuts becomes or remains intractable. Buchanan and Wagner have been stressing this point for decades. A decision to borrow forty cents of a dollar spent, right now, may end up as more or less permanent, at least for as long as markets allow. Ezra’s excellent posts about how far “right” the Democratic Party has moved on taxes are along these lines.

6. Another major recession may arrive, perhaps from abroad.

7. Life expectancy goes up a few more years than we had thought, yet productivity for the elderly doesn’t rise in lockstep. You don’t have to think of that as “bad news,” but it still would be a major fiscal problem.

Maybe none of those are modal forecasts, but add them all up and I say the probability of being way off baseline is greater than 0.5, and possibly more than one of those problems will kick in. In expected value terms, the costs of those possible fiscal scenarios loom very, very large (yet suddenly the modern liberal desire to think in terms of “worst case scenarios” has diminished).

Imagine people sitting around in Spain, in 2006, debating various scenarios relative to the “baseline budget.” Maybe that’s America today, though we do not face the same particular problems or timing that Spain did.

Now enter Chuck Blahous, who wrote an article charging that ACA is likely to prove very costly, and that we are spending our cost savings on Medicare and other programs in advance, when we in fact need those cost savings to restore fiscal sanity. You will find responses here from Ezra Klein, Kevin Drum, Paul Krugman and there were many others, accessible through Google, Blahous counters here.

I have reread the Blahous article carefully, with an eye toward judging whether Blahous is simply playing “baseline games,” as some of the critics allege. I do not see that he is. He stresses that he is making economic, practical, causal, and public choice arguments, and that those trump baseline games in importance. He is trying to get us out of an obsessive focus on the baseline game, not play it in some misleading way.

To be sure, my view, or at least my emphasis, is different from that of Blahous in at least two ways. First, he is more worried about the political economy of Congressional responses when the trust funds are exhausted, whereas I am more worried about the list immediately above (that said, Blahous very clearly does discuss several other major concerns besides double-counting and he may well agree with these broader worries too). Second, my inclination is to focus on the entire budget, as a unified entity, and not so much stand-alone ACA (or Social Security, as in other debates) per se. I suspect Blahous may well agree with me, but as a more active budget analyst/specialist than I am he is forced into debates on stand-alone analyses, whereas I can play the role of aloof blogger. In any case, “fixing” this difference of emphasis would strengthen rather than weaken the overall thrust of his argument.

At the end of the day, I agree with the basic point of Blahous, which is that ACA, should it stand, is spending potentially available budget savings which we will need for other purposes. I also would argue, though I do not have space to do so here, that this has become standard practice in American politics, with Democrats too.

Here are some choice words from Steven Rattner, who worked at Treasury under Obama:

Given that context, the government’s accounting practice — counting $748 billion of cost savings and $259 billion of revenue increases toward both Medicare and the cost of the Obama plan — is particularly troubling. Moreover, this problem is largely hidden from public view.

Under Washington’s delusional rules, budget crunchers in both the White House and Congress credit this $1 trillion twice: once in calculating that the care law will generate more revenues than costs, and again in concluding that the Obama plan will chip away at the Medicare problem.

You can argue that Rattner isn’t quite correctly describing CBO procedures in his piece, but on the economic and causal arguments he, like Blahous, is essentially correct.

At the end of the day, economic models do not use a “relative to baseline” framework. The effect of “Delta G,” “Delta T,” or any other variable, depends on realized and expected values of that variable and others, and not that the size of that variable relative to what other people are proposing. As I mentioned above, “relative to baseline” does have legitimate bureaucratic and accounting uses. But we should not let it blind us to a) the divorce of that mode of reasoning from traditional economics, b) the likely unsustainability of our current fiscal path, and c) that the actual reality of ACA and other policies that we are spending “cost savings” as soon as we create them or even sooner.

Addendum: I am happy to call out the various Ryan budget proposals as unworkable fiscal disasters, most of all on the revenue side. I also refused to endorse the 43 Bush “tax cuts” at the time, though I was sent one of those pieces of paper to sign. No point in throwing the “Team Republican” charge, which in any case disrupts discourse rather than advancing it.

Toward a 21st-Century FDA?

In a WSJ op-ed, Andrew von Eschenbach, FDA commissioner from 2005 to 2009, is surprisingly candid about how the FDA is killing people.

When I was commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 2005 to 2009, I saw firsthand how regenerative medicine offered a cure for kidney and heart failure and other chronic conditions like diabetes. Researchers used stem cells to grow cells and tissues to replace failing organs, eliminating the need for expensive supportive treatments like dialysis and organ transplants.

But the beneficiaries were laboratory animals. Breakthroughs for humans were and still are a long way off. They have been stalled by regulatory uncertainty, because the FDA doesn’t have the scientific tools and resources to review complex innovations more expeditiously and pioneer regulatory pathways for state-of-the-art therapies that defy current agency conventions.

Ultimately, however, von Eschenbach blames not the FDA but Congress:

Congress has starved the agency of critical funding, limiting its scientists’ ability to keep up with peers in private industry and academia. The result is an agency in which science-based regulation often lags far behind scientific discovery.

Should we not, however, read the following ala Strauss?

The FDA isn’t obstructing progress because its employees are mean-spirited or foolish.

…For example, in August 2010, the FDA filed suit against a company called Regenerative Sciences. Three years earlier, the company had begun marketing a process it called Regenexx to repair damaged joints by injecting them with a patient’s own stem cells. The FDA alleged that the cells the firm used had been manipulated to the point that they should be regulated as drugs. A resulting court injunction halting use of the technique has cast a pall over the future of regenerative medicine.

A peculiar example of a patient-spirited and wise decision, no? And what are we to make of this?

FDA scientists I have encountered do care deeply about patients and want to say “yes” to safe and effective new therapies. Regulatory approval is the only bridge between miracles in the laboratory and lifesaving treatments. Yet until FDA reviewers can be scientifically confident of the benefits and risks of a new technology, their duty is to stop it—and stop it they will. (emphasis added).

von Eschenbach ends with what sounds like a threat or perhaps, as they say, it is a promise. Unless Congress funds the FDA at higher levels and lets it regulate itself:

…we had better get used to the agency saying no by calling “time out” or, worse, “game over” for American companies developing new, vital technologies like regenerative medicine.

Frankly, I do not want to “get used” to the FDA saying game over for American companies but nor do I trust Congress to solve this problem. Thus, von Eschenbach convinces me that if we do want new, vital technologies like regenerative medicine we need more fundamental reform.

What if we live longer?

The IMF asks what would happen if life expectancy by 2050 turns out to be three years longer than current projected in government and private retirement plans: “[I]f individuals live three years longer than expected–in line with underestimations in the past–the already large costs of aging could increase by another 50 percent, representing an additional cost of 50 percent of 2010 GDP in advanced economies and 25 percent of 2010 GDP in emerging economies. … [F]or private pension plans in the United States, such an increase in longevity could add 9 percent to their pension liabilities. Because the stock of pension liabilities is large, corporate pension sponsors would need to make many multiples of typical annual pension contributions to match these extra liabilities.”

This is one reason (of several) why “doing fine against the baseline” does not much impress me as a fiscal standard. I hope to cover that broader topic soon.

Does low socioeconomic status have to bring poor health outcomes?

Maybe not, from Edith Chen and Gregory E. Miller:

Some individuals, despite facing recurrent, severe adversities in life such as low socioeconomic status (SES), are nonetheless able to maintain good physical health. This article explores why these individuals deviate from the expected association of low SES and poor health and outlines a “shift-and-persist” model to explain the psychobiological mechanisms involved. This model proposes that, in the midst of adversity, some children find role models who teach them to trust others, better regulate their emotions, and focus on their futures. Over a lifetime, these low-SES children develop an approach to life that prioritizes shifting oneself (accepting stress for what it is and adapting the self through reappraisals) in combination with persisting (enduring life with strength by holding on to meaning and optimism). This combination of shift-and-persist strategies mitigates sympatheticnervous-system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical responses to the barrage of stressors that low-SES individuals confront. This tendency vectors individuals off the trajectory to chronic disease by forestalling pathogenic sequelae of stress reactivity, like insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and systemic inflammation. We outline evidence for the model and argue that efforts to identify resilience-promoting processes are important in this economic climate, given limited resources for improving the financial circumstances of disadvantaged individuals.

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Young vs. old

Three of the top five symptoms searched for on Yahoo Mobile in January were early pregnancy, herpes and H.I.V. None of these symptoms showed up among the top searches on desktop computers, which are more likely to be used by older people.

The most popular symptom searches on PCs included gastroenteritis, heart attacks, gout and shingles, Yahoo said, adding that the encyclopedic medical symptoms checker on WebMD was the most popular site of its kind among PC users. On WebMD, the top symptoms searched for in January were muscle strain, gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome.

…“I do health searches all the time,” said Brittany Lashley, 20, who is majoring in Chinese at the University of Maryland at College Park. She surfs the Web on her iPod Touch for food and drinks that she hopes will increase her energy level and help her stay awake and sharp for late-night studying.

The article is interesting throughout.

Surprising Probability Estimate of the Day

The UK’s Office of Work and Pensions estimates that a child born today has a 30% chance of reaching the age of 100. In contrast, a person 80 years old today has only a 7.7% chance of reaching the age of 100. Indeed, a person today, according to these estimates, has to be about 96.5 years of age to have the same probability of reaching the age of 100 as a newborn.

You can find the data at The Guardian.

Hat tip: John Lanchester’s article on Marx in the LRB.

A future without ACA?

I think that path would look something like this: With health-care reform either repealed or overturned, both Democrats and Republicans shy away from proposing any big changes to the health-care system for the next decade or so. But with continued increases in the cost of health insurance and a steady erosion in employer-based coverage, Democrats begin dipping their toes in the water with a strategy based around incremental expansions of Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. They move these policies through budget reconciliation, where they can be passed with 51 votes in the Senate, and, over time, this leads to more and more Americans being covered through public insurance. Eventually, we end up with something close to a single-payer system, as a majority of Americans — and particularly a majority of Americans who have significant health risks — are covered by the government.

One question is whether having both Medicaid and Medicare (and other programs) function as a “single payer” system, but that is arguably semantics. In any case the American system is likely to remain fragmented. I am also not sure if this process would take a decade, as sometimes a single election cycle can feel like an eternity. In any case, I see that as likely a superior outcome to the current ACA track. I have never thought that a mandate is workable in a fragmented system with employer-based care and high health care costs and high income inequality.

I also would not be surprised to see Romney, if elected, and if ACA is struck down, resurrect some version of the McCain health care plan with tax credits, maybe some more federalism, and less of a Medicaid extension than was in ACA. I don’t know if that would pass but I suppose I think not. I also don’t see much hope for a much-needed “supply-side” competitiveness plan.

The Golden Rule of Organ Donation

Here is Joseph Roth, president and CEO of New Jersey Organ and Tissue Sharing Network:

Caseworkers from our organization recently went to the hospital to visit the family of a woman who suffered a stroke. The woman was dead, but machines continued to keep her organs functioning. She was an ideal candidate to be an organ donor. Her husband, it turns out, was on the waiting list to receive a heart.

Our caseworkers asked the husband if he would allow his wife’s organs to be donated. The husband, to the shock of our caseworkers, said no. He simply refused. Here was a man willing to accept an organ to save his own life, but who refused to allow a family member to give the gift of life to another person.

…Cases like this are rare, thankfully, but are nonetheless troublesome.

Roth continues:

Our proposal — we call it the Golden Rule proposal — would permit health insurers in New Jersey to limit transplant coverage for people who decline to register as organ donors. It would be the first such law in the nation. No one would be denied an organ. But under the proposal, insurers could limit reimbursement for the hospital and medical costs associated with transplants of the kidney, pancreas, liver, heart, intestines and lungs.

I am not in favor of messing with the insurance system for this purpose but have argued for a more direct approach. Under what I call a “no-give, no-take” rule if you are not willing to sign your organ donor card you go to the bottom of the list should you one day need an organ. Israel recently introduced a version of no-give, no take which gives those who previously signed their organ donor cards points pushing them up the list should they need an organ transplant–as a result, tens of thousands of people rushed to sign their organ donor cards.

Hat tip to David Undis whose excellent group Lifesharers (I am an adviser) is implementing a private version of no-give, no take in the United States.

Here is my piece on Life Saving Incentives and here are previous MR posts on organ donation.

At the Frontier of Personalized Medicine

In an essay on frighteningly ambitious startups Paul Graham writes:

…in 2004 Bill Clinton found he was feeling short of breath. Doctors discovered that several of his arteries were over 90% blocked and 3 days later he had a quadruple bypass. It seems reasonable to assume Bill Clinton has the best medical care available. And yet even he had to wait till his arteries were over 90% blocked to learn that the number was over 90%. Surely at some point in the future we’ll know these numbers the way we now know something like our weight. Ditto for cancer. It will seem preposterous to future generations that we wait till patients have physical symptoms to be diagnosed with cancer. Cancer will show up on some sort of radar screen immediately.

An amazing paper in the March 16 issue of Cell illustrates the frontier of what is possible. Geneticist Michael Snyder of Stanford led a team that sequenced his and his mother’s genome. Then, over a two year period they used blood and other assays to track in Snyder’s body transcripts, proteins and metabolites. In the process they generated billions of data points and were able to watch in near real-time what happened as Snyder’s body fought two infections and the surprising onset of diabetes.

From a writeup in Science Daily:

…”We generated 2.67 billion individual reads of the transcriptome, which gave us a degree of analysis that has never been achieved before,” said Snyder. “This enabled us to see some very different processing and editing behaviors that no one had suspected. We also have two copies of each of our genes and we discovered they often behave differently during infection.” Overall, the researchers tracked nearly 20,000 distinct transcripts coding for 12,000 genes and measured the relative levels of more than 6,000 proteins and 1,000 metabolites in Snyder’s blood.

…The researchers identified about 2,000 genes that were expressed at higher levels during infection, including some involved in immune processes and the engulfment of infected cells, and about 2,200 genes that were expressed at lower levels, including some involved in insulin signaling and response.

…The exercise was in stark contrast to the cursory workup most of us receive when we go to the doctor for our regular physical exam. “Currently, we routinely measure fewer than 20 variables in a standard laboratory blood test,” said Snyder, who is also the Stanford W. Ascherman, MD, FACS, Professor in Genetics. “We could, and should, be measuring many, many thousands.”

One side-note: the techniques that the authors use to analyze their time-series data seem (to me) to be behind the curve compared to the VARs used in econometrics. Impulse response functions are what they need! With applications from economics to medicine to marketing, the statistics of big data is the field of the future.

Addendum: Derek Lowe offers further thoughts and Andrew S. points us to this TED video on blood tests without needles.

The return of the house call

In the Netherlands, where else?:

In early March, the NVVE opened the world’s first euthanasia clinic. It’s called the Levenseindekliniek, the “end of life clinic.” It serves as a point of contact for all Dutch people who want to die but don’t have a primary care physician prepared to help them do so. The clinic has mobile euthanasia teams, each of which consists of a doctor and a nurse. When an individual qualifies for the program after passing a screening, one of the teams makes a house call to inject two drugs. One puts the patient into a deep sleep, while the other stops all breathing, leading to death.

The rest of the story is here. And there is this:

The sweets were distributed two years ago as part of a promotional campaign. At the time, her organization was calling for Dutch pharmacies to be allowed to sell lethal drugs to individuals with a prescription. Printed on the wrappers is the word Laatstwilpil, or “last will pill.”

What is the real source of the medical adverse selection problem?

Ray Fisman reports on the job market paper of Nathaniel Hendren, an MIT student on the job market this year. Here is an excerpt from Fisman’s piece:

…sufferers of heart disease and cancer have greater self-knowledge than healthy people in terms of what their likely medical care costs will be. The market for insurance unravels, in Hendren’s model, when patients have a clear view of their future health care costs and people who anticipate lower-cost futures self-select out of insurance coverage.

It’s not about knowing more about your state of health, it is about knowing more about how costly your treatment will be.

Is Medicare cost growth slowing down?

A lot is at stake here. Kevin Drum has a good summary of some recent work:

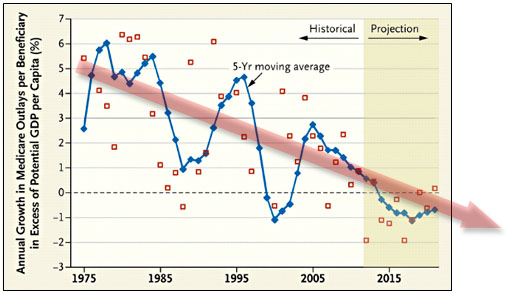

Via Sarah Kliff, a pair of researchers have taken a look at per-capita Medicare spending and concluded that it’s on a long-term downward path which is likely to continue into the future. Their claim is pretty simple: Although Medicare’s sustainable growth rate formula has been overridden year after year (this is the infamous annual “doc fix”), they say that other attempts to rein in spending have actually been pretty effective. This suggests that the cost controls in Obamacare have a pretty good chance of being effective too. Their basic chart is below, and since we’re all about the value-added around here I’ve added a colorful red arrow to indicate the trajectory.

(Note that their calculations are based on potential GDP, not actual GDP. I’m not sure why, but I assume it’s to control for the effects of recessions and boom years.)

Now, this calculation is per beneficiary, which means that overall Medicare costs will still go up if the number of beneficiaries goes up — which it will for the next few decades as the baby boomer generation ages. There’s really nothing to be done about that, though. Demographic bills just have to be paid. Nonetheless, if we can manage to keep benefits per beneficiary stable compared to GDP we’ll be in pretty good shape.

While I would say “too soon to tell” (for me only the post-2005 data points mean very much vis-a-vis the original question), I would not dismiss such reports out of hand.

Charles Murray’s policy proposals

To narrow the class divide, that is. I am almost completely in disagreement (how about more aid and opportunity, less attempted equalization?), the Op-Ed is here. In the form of a list:

1. Apply the minimum wage to internships for the young, so privileged children cannot so easily receive this training.

2. Replace the SAT with specific subject tests.

3. Replace ethnic affirmative action with socioeconomic affirmative action.

4. Sue to challenge the constitutionality of a B.A. degree as a job requirement.

He does admit these proposals will not do so much good in absolute terms, but he nonetheless praises them for their symbolic value.