Category: Philosophy

My excellent Conversation with Mary Gaitskill

Here is the audio and transcript. She is one of my favorite contemporary American writers, most notably in The Mare, Veronica, and Lost Cat. Here is part of the episode summary:

She joined Tyler to discuss the reasons some people seem to choose to be unhappy, why she writes about oddballs, the fragility of personality, how she’s developed her natural knack for describing the physical world, why we’re better off just accepting that people are horrible, her advice for troubled teenagers, why she wouldn’t clone a lost cat, the benefits and drawbacks of writing online, what she’s learned from writing a Substack, what gets lost in Kubrick’s adaptation of Lolita, the not-so-subtle eroticism of Victorian novels, the ground rules for writing about other people, how creative writing programs are harming (some) writers, what she learned about men when working as a stripper, how her views of sexual permissiveness have changed since the ’90s, how college students have changed over time, what she learned working at The Strand bookstore, and more.

It is perhaps a difficult conversation to excerpt from but here is one bit:

COWEN: You once quoted your therapist as saying, and I’m quoting him here, “People are just horrible, and the sooner you realize that, the happier you’re going to be.” What’s your view?

GAITSKILL: [laughs] I thought that was a wonderful remark. It’s important to note the tone of voice that he used. He was a Southern queer gentleman with a very lilting, soft voice. I was complaining about something or other, and he goes, “People are horrible. They’re stupid, and they’re crazy, and they’re mean, and the sooner you realize that, the better off you’ll be, the more you’re going to start enjoying life.”

I just laughed, because partly it was obvious he was being funny, and it was a very gentle way of allowing my ranting and raving and acknowledging the truth of it. Gee, I don’t know how anybody could deny that. Look at human history and some of the things that people do. It was being very spacious about it and just saying, “Look, you have to accept reality. You can’t expect people to be perfect or to be your idea of good or moral all the time. You’re probably not either. This is what it is.”

I thought that was really wisdom, actually.

I am very pleased to have had the chance to chat with her.

Against current conceptions of the equity-efficiency trade-off

I cited the current use of that trade-off as the thing that bugs me most about the economics profession. Here is my Bloomberg column, and here is one excerpt:

The equity-efficiency trade-off, in its simplest form, argues that economists should consider both equity (how a policy affects various interested parties) and efficiency (how well a policy targets the party it is intended to affect) in making policy judgments.

So far so good. I start getting nervous, however, when I see equity given special status. After all, it most often is called “the equity-efficiency trade-off,” not “an equity-efficiency tradeoff,” and it is prominent in mainstream economics textbooks. By simply reiterating a concept, economists are trying to elevate their preferred value over a number of alternatives. They are trying to make economics more pluralistic with respect to values, but in reality they are making it more provincial.

If you poll the American people on their most important values, you will get a diverse set of answers, depending on whom you ask and how the question is worded. Americans will cite values such as individualism, liberty, community, godliness, merit and, yes equity (as they should). Another answer — taking care of their elders, especially if they contributed to the nation in their earlier years — does not always show up in polls, but seems to have a grip on many national policies and people’s minds.

And:

I hear frequently about the equity-efficiency trade-off, but much less about the trade-offs between efficiency and these other values. Mainstream economists seldom debate the value trade-offs between efficiency and individualism, for instance, though such conflicts were of central concern to many Americans during the pandemic…

Surveys have shown that a strong majority of academic economists prefer Democrats. Yet most economists, including Democrats, should pay more attention to the values of ordinary Americans and less attention to the values of their own segment of the intelligentsia. That also would bring them closer to most Democratic Party voters, not to mention swing voters and many Republicans. Equity is just one value of many, and it is not self-evidently the value economists ought to be most concerned with elevating.

Damning throughout.

The wisdom of Bono

I ended up as an activist in a very different place from where I started. I thought that if we just redistributed resources, then we could solve every problem. I now know that’s not true. There’s a funny moment when you realize that as an activist: The off-ramp out of extreme poverty is, ugh, commerce, it’s entrepreneurial capitalism. I spend a lot of time in countries all over Africa, and they’re like, Eh, we wouldn’t mind a little more globalization actually.

And:

Isn’t citing Thomas Piketty a little dicey for you, given what he says about fairer taxation?

Yes, he has a system of progressive taxation and I get it, but the question that I’m compelled to answer is: How are things going for the bottom billion? Be careful to placard the poorest of the poor on politics when they are fighting for their lives. It’s very easy to become patronizing. Capitalism is a wild beast. We need to tame it. But globalization has brought more people out of poverty than any other -ism. If somebody comes to me with a better idea, I’ll sign up. I didn’t grow up to like the idea that we’ve made heroes out of businesspeople, but if you’re bringing jobs to a community and treating people well, then you are a hero. That’s where I’ve ended up. God spare us from lyricists who quote themselves, but if I wrote only one lyric that was any good, it might have been: Choose your enemies carefully because they will define you. Turning the establishment into the enemy — it’s a little easy, isn’t it?

Here is the full NYT interview.

Classical liberalism vs. The New Right

It has become increasingly clear that the political Right in America is not what it used to be. In particular, my own preferred slant of classical liberalism is being replaced. In its stead are rising alternatives that don’t yet have a common name. Some are called “national conservatism,” and some (by no means all) strands are pro-Trump, but I will refer to the New Right. My use of the term covers a broad range of sources, from Curtis Yarvin to J.D. Vance to Adrian Vermeule to Sohrab Ahmari to Rod Dreher to Tucker Carlson, and also a lot of anonymous internet discourse. Most of all I am thinking of the smart young people I meet who in the 1980s might have become libertarians, but these days absorb some mix of these other influences.

I would like to consider where the older classical liberal view differs from these more recent innovations. I don’t so much intend a cataloguing of policy positions as a quest to find the most fundamental difference, at a conceptual level, between the classical liberal views and their New Right competitors. That main difference – to cut to the chase — is how much faith each group puts in the possibility of trustworthy, well-functioning elites.

A common version of the standard classical liberal view stresses the benefits of capitalism, democracy, civil liberties, free trade (with national security exceptions), and a generally cosmopolitan outlook, which in turn brings sympathy for immigration. The role of government is to provide basic public goods, such as national defense, a non-exorbitant safety net, and protection against pandemics.

In the classical liberal view, elites usually fall short of what we would like. They end up captured by some mix of special interest groups and poorly informed voters. There is thus a certain disillusionment with democratic government, while recognizing it is the best of available alternatives and far superior to autocracy for basic civil liberties.

That said, classical liberals do not consider the elites to be totally hopeless. After all, someone has to steer the ship and to this day we do indeed have a ship to steer. Most elites are intelligent and also they are as well-meaning as the rest of us, even if the bureaucratic nature of politics hinders their performance. We can entrust them with supplying basic public goods, and indeed we have little choice. Those truths hold even if the DMV will never be as efficient as Amazon, and even if sometimes our elites commit grave errors, for instance when the Johnson administration escalated the Vietnam War, to cite one example of many.

In the classical liberal view, the great failing of elites is that they do not keep society as free as it ought to be.

The New Right thinkers are far more skeptical of elites. They are more likely to see elites as evil and pernicious, and sometimes they (implicitly) see these evil elites as competent enough to actually wreck society. The classical liberals see checks and balances as strong enough to limit the worst outcomes, whereas the New Right sees ideological conformity and indeed collusion within the Establishment. Checks and balances are a paper tiger.

Once you start seeing elites as so bad and also so collusive, many other changes in your views might follow. You might become more skeptical about free speech, because you view it as a recipe for putting a lot of power in the hands of (often Democratic-led) major tech companies. And is there de facto free speech if a conservative sociologist cannot get hired at Yale? You also might become more skeptical about immigration, not because you are racist (though of course there are racists), but because you see it as a plot of the Democratic Party to remake America in a new image and with a new set of voters (“you will not replace us!”). Free trade becomes seen as a line peddled by the elite, and that is an elite unconcerned with the social and national security costs of a deindustrialized America. Globalization more generally becomes a failed project of the previous elite.

The New Right doesn’t entirely reject the basic principles of free market economics, but it does try to transcend libertarian views with a deeper understanding of the current power structure. In each case there are sociological forces operating that are seen as more important than “mere” free market economics. In this regard the New Right has a more interdisciplinary worldview than do many of the classical liberals. The New Right thinkers regard most power as cultural in nature, rather than rooted in coercive government alone.

Using this kind of contrast, just about every classical liberal view can be redone along New Right lines. The policy emphasis then becomes learning how to use the government to constrain the Left and its cultural agenda, rather than ensuring basic liberties for everyone. The New Right view is that this obsession with basic liberties leads, in reality, to the hegemony of a statist Left, and a Left that will use its power centers of government, media and academia to crush and cancel the New Right.

There is also a self-validating structure to New Right arguments over time. You can’t easily persuade New Right advocates by pointing to mainstream media reports that contradict their main narrative. Mainstream media is one of the least trusted sources. Academic research also has fallen under increasing mistrust, as the academy predominantly hires individuals who support the Democratic Party.

Most classical liberals are uncomfortable with the New Right approaches, and seek to disavow them. I share those concerns, and yet I also recognize that hard and fast lines are not so easy to draw. The New Right is in essence accepting the original classical liberal critique of the state and pushing it a few steps further, adding further skepticism of elites, a greater emphasis on culture, and a belief in elite collusion rather than checks and balances. You may or may not agree with those intellectual moves, but many common premises still are shared between the classical liberals and the New Right, even if neither side is fully comfortable admitting this.

The New Right also tends to see the classical liberals as naïve about power (the same charge classical liberals fling at the establishment), and as standing on the losing side of history. Those aren’t the easiest arguments to refute. Furthermore, the last twenty years have seen 9/11, a failed Iraq War, a major financial crisis and recession, and a major pandemic, mishandled in some critical regards. It doesn’t seem that wrong to become additionally skeptical about American elites, and the New Right wields these points effectively.

While I try my best to understand the New Right, I am far from being persuaded. One worry I have is about how it initially negative emphasis feeds upon itself. Successful societies are based on trust, including trust in leaders, and the New Right doesn’t offer resources for forming that trust or any kind of comparable substitute. As a nation-building project it seems like a dead end. If anything, it may hasten the Brazilianification of the United States rather than avoiding it, Brazil being a paradigmatic example of a low trust society and government.

I also do not see how the New Right stance avoids the risks from an extremely corrupt and self-seeking power elite. Let’s say the New Right description of the rottenness of elites were true – would we really solve that problem by electing more New Right-oriented individuals to government? Under a New Right worldview, there is all the more reason to be cynical about New Right leaders, no matter which ideological side they start on. If elites are so corrupt right now, the force corrupting elites are likely to be truly fundamental.

The New Right also overrates the collusive nature of mainstream elites. Many New Right adherents see a world ever more dominated by “The Woke.” In contrast, I see an America where Virginia elected a Republican governor, Louis C.K. won a 2022 Grammy award on a secret ballot and some trans issues are falling in popularity. Wokism likely has peaked. Similarly, the New Right places great stress on corruption and groupthink in American universities. I don’t like the status quo either, but I also see a world where the most left-wing majors – humanities majors – are losing enrollments and influence. Furthermore, the internet is gaining in intellectual influence, relative to university professors.

The New Right also seems bad at coalition building, most of all because it is so polarizing about the elites on the other side. Many of the most beneficial changes in American history have come about through broad coalitions, not just from one political side or the other. Libertarians such as William Lloyd Garrison played a key role an anti-slavery debates, but they would not have gotten very far without support from the more statist Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln. If you so demonize the elites that do not belong to your side, it is more likely we will end up in situations where all elites have to preside over a morally unacceptable status quo.

The New Right (and the classical liberals I might add) also seem to neglect the many cases where American governance has improved over time. My DMV really is many times better than it was thirty years ago. New York City is currently seeing some trying times, due to the pandemic aftermath, but the city is significant better run today than it was in the 1970s. Social Security, for all of its flaws, remains one of the world’s better-functioning retirement systems. The weapons the U.S. military is supplying to Ukraine seem remarkably effective. The Fed and Treasury, for all their initial oversights, did forestall a great depression in 2008-2009. Operation Warp Speed was a major success and saved millions of lives.

It is missing the point to provide a counter-narrative of all of our government’s major and numerous screw-ups. The point is that good or at least satisfactory elite performance is by no means entirely out of our reach. We then have to ask the question – which philosophy of governance is most likely to get us there next time around? I can see that some New Right ideas might contribute to useful reform, but it is not my number one wish to have New Right leaders firmly in charge or to have New Right ideology primary in our nation’s youth.

Finally, I worry about excess negativism in New Right thinking. Negative thoughts tend to breed further negative thoughts. If the choice is a bit of naivete and excess optimism, or excess pessimism, I for one will opt for the former.

Perhaps most of all, it is dangerous when “how much can we trust elites?” becomes a major dividing line in society. We’ve already seen the unfairness and cascading negativism of cancel culture. To apply cancel culture to our own elites, as in essence the New Right is proposing to do, is not likely to lead to higher trust and better reputations for those in power, even for those who deserve decent reputations.

Very recently we have seen low trust lead to easily induced skepticism about the 2020 election results, and also easily induced skepticism about vaccines. The best New Right thinkers will avoid those mistakes, but still every political philosophy has to be willing to live with “the stupider version” of its core tenets. I fear that the stupider version of some of the New Right views are very hard to make compatible with political stability or for that matter with public health.

I would readily grant that my opinion of our mainstream elites has fallen over the last five to ten years, and in part from consuming intellectual outputs from the New Right. But I don’t long for tearing down the entire edifice as quickly as possible. That would break the remaining bonds of trust and competence we do have, and lead to reconstituted governments, bureaucracies, and media elites with lower competence yet and even less worthy of trust. If you yank out a tooth, you cannot automatically expect a new and better tooth to grow back.

The polarizing nature of much of New Right thought means it is often derided rather than taken seriously. That is a mistake, as the New Right has been at least partially correct about many of the failings of the modern world. But it is an even bigger mistake to think New Right ideology is ready to step into the space long occupied by classical liberal ideals.

A request about philosophy and two people

ymtmjl requested that I cover these topics:

An Effective Altruism mutual fund?

A few days ago I argued that believers in AGI should be “long volatility” in asset markets. Whether or not you agree with that exact prescription, why isn’t there an EA mutual fund, reflecting EA views of the world, whatever those may be? Maybe the fund would instead load up on semiconductor chips, in any case they could aggregate the debates from all those EA forums to make the better decisions.

Presumably EAers are morally obliged to set up such a fund? (I don’t mean that as sarcasm, maybe it really would be a good idea.) EA supporters then could invest in the fund and would over time have more resources to invest in other causes. The fund also could reflect their moral priorities, such as not investing in factory farms (I don’t think any real net loss of diversificatory power would be involved in such a decision.)

Alternatively, you might argue that EA has only moral insight, and no predictive superiority about what will happen at larger levels. That too is a plausible view, especially among non-EAers.

But it seems to me one of these should be true, either that there should be an EA mutual fund, or that EA has only moral insight, not predictive insight. Which is it going to be?

The Invisible Hand Increases Trust, Cooperation, and Universal Moral Action

Montesquieu famously noted that

Commerce is a cure for the most destructive prejudices; for it is almost a general rule, that wherever we find agreeable manners, there commerce flourishes; and that wherever there is commerce, there we meet with agreeable manners.

and Voltaire said of the London Stock Exchange:

Go into the London Stock Exchange – a more respectable place than many a court – and you will see representatives from all nations gathered together for the utility of men. Here Jew, Mohammedan and Christian deal with each other as though they were all of the same faith, and only apply the word infidel to people who go bankrupt. Here the Presbyterian trusts the Anabaptist and the Anglican accepts a promise from the Quaker. On leaving these peaceful and free assemblies some go to the Synagogue and others for a drink, this one goes to be baptized in a great bath in the name of Father, Son and Holy Ghost, that one has his son’s foreskin cut and has some Hebrew words he doesn’t understand mumbled over the child, others go to heir church and await the inspiration of God with their hats on, and everybody is happy.

Commerce makes people traders and by and large traders must be benevolent, agreeable and willing to bargain and compromise with people of different sects, religions and beliefs. Contrary to what one naively might expect, people with more exposure to markets behave more cooperatively and in less nakedly self-interested ways. Similarly, in a letter-return experiment in Italy, Baldassarri finds that market integration increases pro-social behavior towards in and outgroups:

In areas where market exchange is dominant, letter-return rates are high. Moreover, prosocial behavior toward ingroup and outgroup members moves hand in hand, thus suggesting that norms of solidarity extend beyond group boundaries.

Also, contrary to what you may have read about the mythical Wall Street game versus Community game, priming people in the lab with phrases evocative of markets and trade, increases trust.

In a new paper, Gustav Agneman and Esther Chevrot-Bianco test the idea that markets generate more universal behavior. They run their tests in villages in Greenland where some people buy and sell in markets for their primary living while others in the same village still rely for a substantial part of their subsistence on hunting, fishing and personal exchange. They use a dice game in which players report the number of a roll with higher numbers being better for the player. Only the player knows their true roll and there is no way to detect cheaters on an individual basis. In some variants, other people (in-group or out-group) benefit when players report lower numbers. The upshot is that people exposed to market institutions are honest while traditional people cheat. Cheating is only ameliorated in the traditional group when cheating comes at the expense of an in-group (fellow-villager) but not when it comes at the expense of an out-grou member. More generally the authors summarize:

…We conduct rule-breaking experiments in 13 villages across Greenland (N=543), where stark contrasts in market participation within villages allow us to examine the relationship between market participation and moral decision-making holding village-level factors constant. First, we document a robust positive association between market participation and moral behaviour towards anonymous others. Second, market-integrated participants display universalism in moral decision-making, whereas non-market participants make more moral decisions towards co-villagers. A battery of robustness tests confirms that the behavioural differences between market and non-market participants are not driven by socioeconomic variables, childhood background, cultural identities, kinship structure, global connectedness, and exposure to religious and political institutions.

Markets and trade increase trust, cooperation and universal moral action–it is hard to think of a more important finding for the world today.

Hat tip: The still excellent Kevin Lewis.

Effective Altruism and the Repugnant Conclusion

Here is an excellent essay by Peter McLaughlin, here is one excerpt:

So, the problem is this. Effective Altruism wants to be able to say that things other than utility matter—not just in the sense that they have some moral weight, but in the sense that they can actually be relevant to deciding what to do, not just swamped by utility calculations. Cowen makes the condition more precise, identifying it as the denial of the following claim: given two options, no matter how other morally-relevant factors are distributed between the options, you can always find a distribution of utility such that the option with the larger amount of utility is better. The hope that you can have ‘utilitarianism minus the controversial bits’ relies on denying precisely this claim.

This condition doesn’t aim to make utility irrelevant, such that utilitarian considerations should never change your mind or shift your perspective: it just requires that they can be restrained, with utility co-existing with other valuable ends. It guarantees that utility won’t automatically swamp other factors, like partiality towards family and friends, or personal values, or self-interest, or respect for rights, or even suffering (as in the Very Repugnant Conclusion). This would allow us to respect our intuitions when they conflict with utility, which is just what it means to be able to get off the train to crazy town.

Now, at the same time, Effective Altruists also want to emphasise the relevance of scale to moral decision-making. The central insight of early Effective Altruists was to resist scope insensitivity and to begin systematically examining the numbers involved in various issues. ‘Longtermist’ Effective Altruists are deeply motivated by the idea that ‘the future is vast’: the huge numbers of future people that could potentially exist gives us a lot of reason to try to make the future better. The fact that some interventions produce so much more utility—do so much more good—than others is one of the main grounds for prioritising them. So while it would technically be a solution to our problem to declare (e.g.) that considerations of utility become effectively irrelevant once the numbers get too big, that would be unacceptable to Effective Altruists. Scale matters in Effective Altruism (rightly so, I would say!), and it doesn’t just stop mattering after some point.

There is much more to the argument, recommended.

The End of History (of Philosophy)

Hanno Sauer on why philosophers spend far too much time reading and writing about dead philosophers:

Hanno Sauer on why philosophers spend far too much time reading and writing about dead philosophers:

What credence should we assign to philosophical claims that were formed without any knowledge of the current state of the art of the philosophical debate and little or no knowledge of the relevant empirical or scientific data? Very little or none. Yet when we engage with the history of philosophy, this is often exactly what we do. In this paper, I argue that studying the history of philosophy is philosophically unhelpful. The epistemic aims of philosophy, if there are any, are frustrated by engaging with the history of philosophy, because we have little reason to think that the claims made by history’s great philosophers would survive closer scrutiny today. First, I review the case for philosophical historiography and show how it falls short. I then present several arguments for skepticism about the philosophical value of engaging with the history of philosophy and offer an explanation for why philosophical historiography would seem to make sense even if it didn’t.

A devastating example:

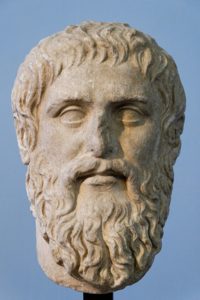

Consider Plato’s or Rousseau’s evaluation of the virtues and vices of democracy. Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of evidence and theories that were unavailable to them at the time:

- Historical experiences with developed democracies

- Empirical evidence regarding democratic movements in developing countries

- Various formal theorems regarding collective decision making and preference aggregation, such as the Condorcet Jury-Theorem, Arrow’s Impossibility-Results, the Hong-Page-Theorem, the median voter theorem, the miracle of aggregation, etc.

- Existing studies on voter behavior, polarization, deliberation, information

- Public choice economics, incl. rational irrationality, democratic realism

The whole subsequent debate on their own arguments…When it comes to people currently alive, we would steeply discount the merits of the contribution of any philosopher whose work were utterly uninformed by the concepts, theories and evidence just mentioned (and whatever other items belong on this list). It is not clear why the great philosophers of the past should not be subjected to the same standard. (Bear in mind that time and attention are severely limited resources. Therefore, every decision we make about whose work to dedicate our time and attention to faces important trade-offs.)

This is obviously true so I think the more interesting question is why do philosophers do this?

Hat tip: Jason Brennan

Who are the odious figures?

Tyler: But even that phrase, odious figures, I’m made uncomfortable by. Like okay, you can cite Hitler. Hitler’s odious. I think we make ourselves stupider. I like to ask this question: does this person favor price controls on prescription drugs? Well, they might, they might not. To me, that’s a terrible view that will kill many thousands of people, maybe more. But I don’t think of those people as odious. I think, they’re wrong about something. If someone’s called odious, I’ll just ask myself, well, are their views worse than the views of someone who wants price controls on prescription drugs? [laughter] Like, who’s odious? I know there’s the Hitler thing, and Godwin’s law, but we have got to mostly move past that, and just focus on the ideas and being more analytical.

That is from my podcast dialogue with Richard Hanania from a few weeks ago. Don’t forget that Columbia researcher Frank Lichtenberg calculates the average pharmaceutical expenditure per life-year saved (globally) at $2,837. Let’s spend more on this one! And in multiple ways. In the meantime, don’t be so obsessed with what other people think and write — focus on the issues themselves.

*Magnificent Rebels*

The author is the excellent Andrea Wulf and the subtitle is The First Romantics and the Invention of the Self. The focus is on the German group of thinkers who worked together in or near Jena, including the Schlegels, Novalis, Schiller, Goethe and Schelling, with a later cameo from Hegel. This is one of my favorite books of the year, but note it focuses mostly on their personal stories and not so much on their ideas. Perfect for me, but not the ideal introduction for every reader. And their ideas are hard to explain! Their emphasis on imagination and subjectivity has been so absorbed into the modern world it can be hard to grasp their revolutionary nature at the time. Context is that which is scarce. Recommended nonetheless.

The new Bryan Caplan book

The title has attracted a lot of attention and controversy, it is Don’t be a Feminist: Essays on Genuine Justice, description here. Bryan writes a letter to his daughter, telling her not to be a feminist.

To counter Bryan, many people are trying to cite the “official” definition of feminism, which runs something like:

feminism, the belief in social, economic, and political equality of the sexes.

Who could not believe in that? But here is a case where the official definition (which comes in varying versions) is off base. Many people do not consider themselves feminists but would endorse those conclusions or come close to endorsing those conclusions entirely (I’m not sure what “social” equality for the sexes is supposed to mean.) Or can’t you be a pretty radical fighter for women’s rights, without necessarily believing full equality (of which kind?) is possible? What if you thought women shouldn’t be drafted into the military for combat? Would that disqualify you? Could Mary Wollstonecraft qualify on that basis? Yet Wikipedia presents her as the founder of feminism.

Bryan’s preferred definition of feminism is:

feminism: the view that society generally treats men more fairly than women

That also seems off base to me. If you were a feminist, but all of a sudden society does something quite unfair to men (drafts them to fight an unjust and dangerous war?), does that mean you might have to stop calling yourself a feminist? Somehow the definition ought to be more weighted toward the status of women and remedies for women, rather than treating men and women symmetrically. It seems weird to get people thinking about all of the injustices faced by men.

I don’t go around calling myself a feminist. There is too much in “the other people who call themselves feminists” that I don’t agree with. And it seems to me too aggregative a notion, and furthermore an attempt to win an argument by putting forward a definition that other people will be afraid to countermand. Nonetheless here is a view I do agree with:

There is an important emancipatory perspective, one that would improve the lives of many women, and it consists of a better understanding of how social institutions to date have disadvantaged women, and a series of proposals for improvement. Furthermore large numbers of men still do not understand the import of such a perspective, one reason for that being they have never lived the lives of women.

Unlike Bryan’s definition, this puts the treatment of women at the center of the issue. And unlike some of the mainstream definitions, it does not focus on the issue of equality, which I think will be difficult to meet or even define. Do we have to let men play in women’s tennis? In women’s chess tournaments? Whether yes or no, I don’t think the definition of feminism should hinge on those questions.

If you want to call that above description of mine feminism, fine, but I am finding that word spoils more debates and discussions than it improves. I won’t be using it. By the way, John Stuart Mill’s On the Subjection of Women remains one of the very best books ever written, on any topic, and indeed I have drawn my views from Mill. Everyone should read it. He never used the word feminist either.

I also would stress that my definition does not rule out emancipatory perspectives for men or other gender categories, or for that matter other non-gender categories, quite the contrary. Freedom and opportunity are at the center of my conception, and that means for everybody, which allows for a nice kind of symmetry.

In the meantime, I will read Bryan’s book once it comes out Monday. I’ve seen its component pieces already in Bryan’s other writings, I just am not sure which ones are in the book.

By the way, I wonder if Bryan’s views on gender are fully consistent with his views on poverty. He advocates marrying, staying married, etc., that whole formula thing. But if men are treated so badly in society, maybe in many cases there just aren’t enough marriageable men to go around? What are the women (and the men) to do then?

*Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality*

Now on Amazon for pre-order, due out April 18, 2023.

By Dave Edmonds. I read an earlier version and it was just fantastic.

Is “imposter syndrome” a good thing?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Impostor syndrome is a positively good thing. When searching for talent, I look for people who feel they suffer from impostor syndrome. If you think you are not qualified to do what you are doing, it is a sign you are setting your sights high and reaching for a new and perhaps unprecedented level of achievement…

Another advantage to feeling like an impostor is that it gives you better insight into your fellow humans. Estimates vary, but up to 82% of people may suffer from some form of impostor syndrome. Even if that is on the high side, impostor syndrome is very common. On a professional level, if you want to be in better touch with your colleagues, maybe it is a good idea for you to try out some new and unfamiliar tasks, and they can too. It will make everyone more understanding and more sympathetic — especially important qualities for being a successful boss.

Recommended. And if you are not currently an impostor, perhaps you should try impersonating one!

Shruti Rajagopalan talks talent with Daniel Gross and Tyler

A Conversation, a special bonus episode, taped in San Francisco in front of a live audience, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is one bit:

RAJAGOPALAN: …Daniel, if you’re looking for talent in investing or finance, how does that look different from the talent in the start-up world?

GROSS: In the start-up world? What makes a good investor is very different from what makes a good founder. If you were to make a scatterplot of it, some of the attributes are completely diametrically opposed. For example, I think very good investors are the right degree of optimistic but also realistic, whereas founders are too optimistic, which they should be.

At the end of the day, start-ups are a very funny activity when you think about it from a probability standpoint. Most companies fail. Almost all companies fail, and yet, people seem to be seemingly doing this activity over and over. They’re jumping off the cliff over and over again. You look over the cliff, and everyone who jumped off of the cliff is just on the ground dead, but people keep on jumping off the cliff. Founders are almost too optimistic.

When you’re evaluating a business, especially at later and later stages, I think optimism can be your enemy. Often, you see when a lot of founders later on in life — and I’m such a person — who started a business, sold it, and became an investor, you actually have to be able to wear very different kinds of psychometric hats. One of them is this continuum of realism and optimism. I’d probably say that’s the starkest difference between what makes a good start-up investor and a good founder. There are probably many others, but that’s the main thing that you look for.

I later have a monologue on chocolate ice cream, but overall Shruti steals the show. Recommended.

In order:

1. Jeffrey Sachs is a brilliant and much underrated economist, here is my early CWT with him. His work on economic geography and development remains neglected, his “shock therapy” reforms in Poland worked, they didn’t listen to him in Russia, and the Millennium Villages project, while it did not obviously succeed, was a noble and impressive attempt. He deserves a Nobel Prize for that work. His marginal input in Bolivia was positive. That said, I find some of his recent comments on China/Lab Leak and Russia/Nordstream deeply objectionable and one can only theorize about what is going on there. In part he imbibed too much “New Left” foreign policy reasoning from the 1960s crew, but I don’t think that is the entirety of it by any means.

2. Is there any point in my mentioning the obvious famous figures such as Kripke, Bernard Williams, Latour, and so on? As for other favorites, see CWT! (Unlike Paul McCartney, most philosophers will in fact say yes to these dialogues.) I also would stress that a lot of the best philosophy is done by “drive-by commentators” on the internet, and what is philosophical is the dialogical internet mechanism as a whole, as a kind of epistemic computer above and beyond any individual’s contributions.

3. Most major philosophers are underrated, with the exception of Althusser, who strangled and murdered his wife.

4. Some individuals have been invited who still have not yet said yes. Not just Paul McCartney.