Category: Philosophy

*Inventing Freedom*

That is the new book by Daniel Hannan and the subtitle is How the English-Speaking Peoples Made the Modern World.

Oh how one can mock those subtitles about the making of the modern world, heh heh! Yet this subtitle has a plausible claim to be…true. Even more shockingly, the subtitle accurately describes the book.

Every time my plane lands in England I shed at least a tear, maybe more, out of realization that I am visiting a birthplace (the birthplace?) of liberty. This is not a joke and during my trips there I never quite snap out of that feeling, though I am also well aware of all the problems those people have foisted upon the world as well.

I found many parts of this book to be superficial, or perhaps well-known. Yet often they were superficial and…true. Here is one excerpt:

To put it another way, the distinction was not between Catholic and Protestant individuals, but between Catholic and Protestant states.

Here is from an Amazon review:

Author Daniel Hannan is a person of English ancestry who was born and raised in Peru then relocated to the United Kingdom as an adult and made a career in politics, including becoming one of the U.K.’s representatives to the European Parliament. His global experience has shown him how unique is our “Anglosphere” heritage of representative democracy, protection of property rights, the sanctity of law, and the inalienable rights of the individual.

This is in some ways an important book, though I do not think it is a book which will satisfy everybody.

For the pointer I thank Daniel Klein.

*The Curmudgeon’s Guide to Getting Ahead*

That is the new forthcoming Charles Murray book and the subtitle is Dos and Don’ts of Right Behavior, Tough Thinking, Clear Writing, and Living a Good Life.

Murray by the way just published a review of Average is Over in the latest Claremont Review of Books which I enjoyed very much. It is not yet on-line but cited here.

For the pointer I thank Alex.

Why blame only the Republicans?

When I blame people for their problems, Democrats and liberals are prone to object at a fundamental level. One fundamental objection rests on determinism: Since everyone is determined to act precisely as he does, it is always false to say, “There were reasonable steps he could have taken to avoid his problem.” Another fundamental objection rests on utilitarianism: We should always do whatever maximizes social utility, even if that means taxing the blameless to subsidize the blameworthy.

Strangely, though, every Democrat and liberal I know routinely blames one category of people for their vicious choices: Republicans…

Personally, I strongly favor blaming Republicans. I think 80% of the blame heaped on Republicans is justified. What mystifies me, however, is the view that Republicans are somehow uniquely blameworthy. If you can blame Republicans for lying about WMDs, why can’t you blame alcoholics for lying to their families about their drinking? If you can blame Republican leaders for supporting bad policies because they don’t feel like searching for another job, why can’t you blame able-bodied people on disability because they don’t feel like searching for another job?

Democrats and liberals who expand their willingness to blame do face a risk: You will occasionally sound like a Republican! But why is that such a big deal? Maybe you’ll lose a few intolerant hard-left friends, but they’re replaceable. By taking a reasonable step – broadening your blame – you can avoid the vices of moral inconsistency and moral nepotism. To do anything less would be… blameworthy.

That is from Bryan Caplan. As Robin Hanson once opined, “politics isn’t about policy.”

My own view is to minimize blame in all directions, but of course Bryan is correct in pointing out this inconsistency. Most people are willing to blame those whom they seek to lower in relative status, though I can’t say I really blame them for that.

Markets in everything

Horse head squirrel feeder. Who could possibly want such a thing? Is that the result of a fixed point theorem? Aren’t fixed costs God’s way of keeping such nasty stuff away from us?:

You have a Creepy Horse Mask, why not the squirrels in your yard? It turns out it’s even funnier on a squirrel. This hanging vinyl 6-1/2″ x 10″ squirrel feeder makes it appear as if any squirrel that eats from it is wearing a Horse Mask. You’ll laugh every morning as you drink your coffee while staring out the window into your backyard. Now, if only the squirrels would do their own version of the Harlem Shake video. Hole on top for hanging with string (not included).

For the pointer I thank John De Palma.

What I worry about

LATimes: A 30,000-year-old giant virus has been revived from the frozen Siberian tundra, sparking concern that increased mining and oil drilling in rapidly warming northern latitudes could disturb dormant microbial life that could one day prove harmful to man.

The original research is here. Have a nice day.

New trend of people naming their kids after guns

Via Kottke, here is Abby Haglage:

In 2002, only 194 babies were named Colt, while in 2012 there were 955. Just 185 babies were given the name Remington in 2002, but by 2012 the number had jumped to 666. Perhaps the most surprising of all, however, is a jump in the name Ruger’s (America’s leading firearm manufacturer) from just 23 in 2002 to 118 in 2012. “This name [Ruger] is more evidence of parents’ increasing interest in naming children after firearms,” Wattenberg writes. “Colt, Remington, and Gauge have all soared, and Gunner is much more common than the traditional name Gunnar.”

Practical gradualism vs. moral absolutism, for immigration and revolution

After reading Alex’s post I was a bit worried I would wake up this morning and find the blog retitled, maybe with a new subtitle too. Just a few quick points:

1. There is a clear utilitarian case against open borders, namely that it will — in some but not all cases — lower the quality of governance and destroy the goose that lays the golden eggs. The world’s poor would end up worse off too. I wonder if Alex will apply his absolutist idea on fully open borders to say Taiwan.

2. Alex’s examples don’t support his case as much as he suggests. The American Revolution compromised drastically on slavery, among other matters. (And does Alex even favor that revolution? Should he? Can you be a moral absolutist on both that revolution and on slavery?) American slavery ended through a brutal war, not through the persuasiveness of moral absolutists per se. The British abolished slavery for off-shore islands, but they were very slow to dismantle colonialism, and would have been slower yet if not for two World Wars and fiscal collapse. Should the British anti-slavery movement have insisted that all oppressive British colonialism be ended at the same time? You may argue this one as you wish, but the point is one of empirics, not that the morally absolutist position is generally better.

3. Gay marriage is like “open borders for Canadians.” I’m for both, but I don’t see many people succeeding with the “let’s privatize marriage” or “let’s allow any consensual marriage” arguments, no matter what their moral or practical merits may be. Gay marriage advocates were wise to stick with the more practical case, again choosing an interior solution. Often the crusades which succeed are those which feel morally absolute to their advocates and which also seem like practically-minded compromises to moderates and the undecided.

4. Large numbers of important changes have come quite gradually, including women’s rights, protection against child abuse, and environmentalism, among others. I don’t for instance think parents should ever hit their children, but trying to make further progress on children’s rights by stressing this principle is probably a big mistake and counterproductive.

5. The strength of tribalist intuitions suggests that the moral arguments for fully open borders will have a tough time succeeding or even gaining basic traction in a world where tribalist sentiments have very often been injected into the level of national politics and where, nationalism, at least in the wealthier countries, is perceived as working pretty well. The EU is by far the biggest pro-immigration step we’ve seen, which is great, but we’re seeing the limits of how far that can be pushed. My original post gave some good evidence that a number of countries — though not the United States — are pretty close to the point of backlash from further immigration. Rather than engaging such evidence, I see many open boarders supporters moving further away from it.

6. In the blogosphere, is moralizing really that which needs to be raised in relative status?

Addendum: Robin Hanson adds comment.

And: Alex responds in the comments:

Some good points but only point number #5 actually addresses my argument. I argued that strong, principled moral arguments are most likely to succeed. Point #5 rests on mood affiliation. I know because having a different mood I read the facts in that point in entirely the opposite way. Namely that it’s amazing that although our moral instincts were built on the tribe we have managed to expand the moral circle far beyond the tribe. Having come so far I see no reason why we can’t continue to expand the moral circle to include all human beings. The open borders of the EU is indeed a triumph. Let’s create the same thing with Canada and then lets join with the EU.

Do not make the mistake (as in point #2) of thinking that the moral argument only succeeds when we make fully moral choices. It also succeeds by pushing people to move in the right direction when other arguments would not do that at all.

The Moral Is the Practical

Tyler concedes the moral high ground to advocates of open borders but argues that the proposal is “doomed to fail and probably also to backfire in destructive ways.” In contrast, I argue that the moral high ground is tactically the best ground from which to launch a revolution. In Entrepreneurial Economics I wrote:

No one goes to the barricades for efficiency. For liberty, equality or fraternity, perhaps, but never for efficiency.

Contra Tyler, the lesson of history is that few things are as effective at launching a revolution as is moral argument. Without the firebrand Thomas “We have it in our power to begin the world over again“ Paine, the American Revolution would probably never have happened. Paine’s Common Sense, the most widely read book of its time, is about as far from Tyler’s synthetic, marginalist argument as one can imagine and it was effective.

When in 1787 Thomas Clarkson founded The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade a majority of the world’s people were held in slavery or serfdom and slavery was considered by almost everyone as normal, as it had been considered for thousands of years and across many nations and cultures. Slavery was also immensely profitable and woven into the fabric of the times. Yet within Clarkson’s lifetime slavery would be abolished within the British Empire. Whatever one may say about this revolution one can certainly say that it was not brought about by a “synthetic and marginalist” approach. If instead of abolition, Clarkson had settled on the goal of providing for better living conditions for slaves on the voyage from Africa it seems quite possible that slavery would still be with us today.

When in 1787 Thomas Clarkson founded The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade a majority of the world’s people were held in slavery or serfdom and slavery was considered by almost everyone as normal, as it had been considered for thousands of years and across many nations and cultures. Slavery was also immensely profitable and woven into the fabric of the times. Yet within Clarkson’s lifetime slavery would be abolished within the British Empire. Whatever one may say about this revolution one can certainly say that it was not brought about by a “synthetic and marginalist” approach. If instead of abolition, Clarkson had settled on the goal of providing for better living conditions for slaves on the voyage from Africa it seems quite possible that slavery would still be with us today.

In more recent times, civil unions have gone nowhere while equality of marriage has succeeded beyond all expectation. The problem with civil unions, and with the synthetic and marginalist approach more generally, is that even though it offers everyone something that they want, it concedes the moral high ground–perhaps there is something different about gay marriage which makes it ok to treat it differently–and for that reason it attracts few adherents. Moreover, the argument for civil unions doesn’t force the opposition to enunciate the moral arguments for their opposition and when the moral ground of the opposition is weak that is a strategic failure.

The moral argument for open borders is powerful. How can it be moral that through the mere accident of birth some people are imprisoned in countries where their political or geographic institutions prevent them from making a living? Indeed, most moral frameworks (libertarian, utilitarian, egalitarian, and others) strongly favor open borders or find it difficult to justify restrictions on freedom of movement. As a result, people who openly defend closed borders sound evil, even when they are simply defending what most people implicitly accept. When your opponents occupy ground that they cannot–even on their own moral premises–defend then it is time to attack.

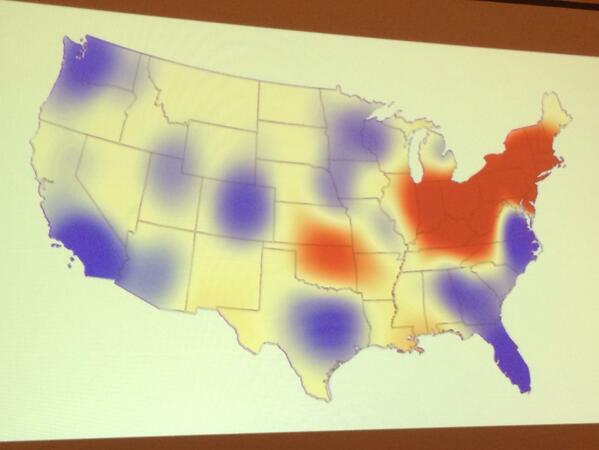

Personality by region

As indicated by words on blogs: red is high neurotic, blue is low. Highly speculative of course:

How beautiful is mathematics?

From James Gallagher of the BBC:

Mathematicians were shown “ugly” and “beautiful” equations while in a brain scanner at University College London.

The same emotional brain centres used to appreciate art were being activated by “beautiful” maths.

The researchers suggest there may be a neurobiological basis to beauty.

The likes of Euler’s identity or the Pythagorean identity are rarely mentioned in the same breath as the best of Mozart, Shakespeare and Van Gogh.

The study in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience gave 15 mathematicians 60 formula to rate.

Euler’s Identity is a particular favorite of mine, and indeed:

The more beautiful they rated the formula, the greater the surge in activity detected during the fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scans.

…To the untrained eye there may not be much beauty in Euler’s identity, but in the study it was the formula of choice for mathematicians.

Oh, and this:

In the study, mathematicians rated Srinivasa Ramanujan’s infinite series and Riemann’s functional equation as the ugliest of the formulae.

For the pointer I thank Joanna Syrda.

Why cosmopolitanism is utopian but useful nonetheless

On the topic of Swiss immigration restrictions, Bryan Caplan has an interesting (but I think quite wrong) recent post about the recent immigration vote in Switzerland. He writes:

The main hurdle to further immigration is insufficient immigration. If countries could just get over the hump of status quo bias, anti-immigration attitudes would become as socially unacceptable as domestic racism. Instead of coddling nativism with gradualism, we can, should, and must peacefully destroy nativism with abolitionism.

In other words, we should keep on letting more people in until nativist bias dwindles away into the dustbin of history. I say backlash will set in first, as I have never met a truly cosmopolitan Volk, the cosmopolitanites least of all. I would say Bryan has the moral high ground but not a practicable proposal. Nonetheless we can and should favor less nativism and more immigration at the margin.

Steve Sailer of course is far more skeptical about immigration and he serves up — repeatedly I might add — general strictures in favor of a particularist approach to policy and to immigration in particular. Try this bit from his discussion of Switzerland:

The Swiss, in contrast, put much value on what I call Citizenism. A Swiss Italian is expected to value the welfare of his fellow Swiss citizens more highly than his fellow Italian co-ethnics. And they do.

He expresses related ideas in other posts as well.

My perspective is a synthetic one. Citizenries will in fact always be Citizenist (surprise) and to some extent this is needed to encourage the production of public goods. Caplanian proposals to make citizens otherwise are doomed to fail and probably also to backfire in destructive ways.

Now enter the intellectuals, whom I call The False Cosmopolitanites. The intellectuals, for all of their failings, nonetheless see many of the defects and costs of Citizenism as we find it in the world. The intellectuals therefore should push for marginal moves toward a stronger cosmopolitanism, even though in a deconstructionist sense their inflated sense of superiority and smugness, while doing so, is its own form of non-cosmopolitanism. Sailer’s failing is to think or imply that the costs of The False Cosmopolitanites are higher, or more worthy of scorn, than the costs of Citizenism, and also the costs of other particularist doctrines, some of which are less savory than Citizenism by some degree. The comparison of where the major injustices are generated is not even close.

Both the Caplan memes and the Sailer memes can generate an unending supply of entertaining and indeed edifying blog posts. Caplan can point to the fallacies of the Citizenists, which are numerous, extreme, and which create high humanitarian costs, including through war and unnecessary immigration restrictions. Sailer can skewer The False Cosmopolitanites, who serve up a highly elastic and never-ending supply of objectionable, fact-denying, self-righteous nonsense. Blog post by blog post, either approach will appear to “work” in its own terms. And blog post by blog post, either approach will be susceptible to attack by outsiders who insist on the opposing perspective.

It is only the synthetic and marginalist cosmopolitan approach which sees its way through this thicket.

Embedded in all of this, Caplan is more particularistic than he lets on, embodying and glorifying a form of upper-middle class U.S. suburban culture of which I am personally quite fond. Sailer is de facto less on his actual professed side than his own writings will admit, and in fact a group of ardent Citizenists, if they were informed enough to apply their doctrines consistently, might cut him down some notches as a non-conformist and smart aleck who plays at the status games of The False Cosmopolitanites. Sailer insists on relativizing and deconstructing The False Cosmopolitanites, which is fine by me, but at the same time he overestimates their power and influence and thus he falsely imagines a need to take up common cause with the Citizenists, a group it seems he enjoys more from a distance.

You will find related ideas in my book Creative Destruction: How Globalization is Changing the World’s Cultures. And here are by the way are my previous posts on horse nationalism.

Gabriel Axel, RIP

He was the director of Babette’s Feast and he just passed away at age 95. What stuck with me most from that movie, and what is one of my favorite sentences ever, Axel himself cited upon receiving an Oscar:

Mr. Axel was a week shy of his 70th birthday when he took the podium in Los Angeles in April 1988 to accept the award. After saying his thank-yous, he quoted a line from his film: “Because of this evening, I have learned, my dear, that in this beautiful world of ours, all things are possible.”

The obituary is here.

Equilibrium vs. disequilibrium?

Adolfo Laurenti writes on Facebook:

Reminiscences from Tyler Cowen‘s macroeconomics class: “there are three ways to think about market equilibrium: (i) markets are always in equilibrium, (ii) markets are sometimes in equilibrium, and (iii) markets are never in equilibrium. And (i) and (iii) are much closer and alike than (i) and (ii) or (iii) and (ii).” Is this Tyler’s oral tradition only? I do not know if he put this down in writing anywhere. Anyone with a reference?

I meant that as a Quinean point of course.

Words of wisdom from Bryan Caplan

BC: Every economist who gives policy advise is implicitly relying on philosophy. Unfortunately, most economists want to rely on philosophy without really reflecting on it, so they’re usually just crude utilitarians (with a heavy bias toward the status quo and democratic fundamentalism).

And:

The certainty of the “New Atheists”

From the excellent Jonathan Haidt:

…I took the full text of the three most important New Atheist books—Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion, Sam Harris’s The End of Faith, and Daniel Dennett’s Breaking the Spell and I ran the files through a widely used text analysis program that counts words that have been shown to indicate certainty, including “always,” “never,” “certainly,” “every,” and “undeniable.” To provide a close standard of comparison, I also analyzed three recent books by other scientists who write about religion but are not considered New Atheists: Jesse Bering’s The Belief Instinct, Ara Norenzayan’s Big Gods, and my own book The Righteous Mind. (More details about the analysis can be found here.)

To provide an additional standard of comparison, I also analyzed books by three right wing radio and television stars whose reasoning style is not generally regarded as scientific. I analyzed Glenn Beck’s Common Sense, Sean Hannity’s Deliver Us from Evil, and Anne Coulter’s Treason. (I chose the book for each author that had received the most comments on Amazon.) As you can see in the graph, the New Atheists win the “certainty” competition. Of the 75,000 words in The End of Faith, 2.24% of them connote or are associated with certainty. (I also analyzed The Moral Landscape—it came out at 2.34%.)

There is more here, and for the pointer I thank Eric Auld.