Category: Science

The Schelling-Stapledon model of the Octopus

Octopuses have large nervous systems, centered around relatively large brains. But more than half of their 500 million neurons are found in the arms themselves, Godfrey-Smith said. This raises the question of whether the arms have something like minds of their own. Though the question is controversial, there is some observational evidence indicating that it could be so, he said. When an octopus is in an unfamiliar tank with food in the middle, some arms seem to crowd into the corner seeking safety while others seem to pull the animal toward the food, Godfrey-Smith explained, as if the creature is literally of two minds about the situation.

The full story is here and for the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Chromosomal clubs?

…a few months earlier, a newly available DNA test revealed that Samantha and Taygen share an identical nick in the short arm of their 16th chromosomes…

Some mutations are so rare that they are known only by their chromosomal address: Samantha and Taygen are two of only six children with the diagnosis “16p11.2.”

It turns out that individuals (and their parents) who share these diagnoses are meeting and exchanging information and forming mini-alliances. Here is the full story, though I am not entirely comfortable with the tone and selection of the article as a whole — only negatives, for one thing. Rare copy variations also may be a significant source of human progress and, for that matter, individual contentment.

For the pointer I thank Andrew S.

Markets in everything very good subtitles on the article

I liked this one:

Market forces govern a baby’s value among vervet monkeys and sooty mangabeys

The full article is here. I was not surprised to learn that a sooty mangabey is, indeed, sooty in color.

For the pointer I thank Kathleen Fasanella and Chris Valickas.

Claims I wish I understood — quantum Darwinism

The resulting theory of Quantum Darwinism is relatively straightforward:

1) Human measurements are only one, rather unusual, means of forcing decoherence of a superposed or entangled quantum state into simpler states. The primary mechanism causing decoherence is the many types of interactions that the quantum system has with its environment. Typically quantum systems experience a vast number of such environmental interactions selectively destroying entangled quantum states.

2) As a result these environmental interactions, or environmental monitoring, only a small minority of quantum states, called pointer observables, are able to survive and evolve for any sustained period of time in the deterministic, classical manner of axiom 5 above. Their prolonged survival is due to the peculiar property of these pointer states that interactions with the environment and the subsequent decoherence leave them largely unchanged. They alone are able to survive in the face of environmental monitoring.

3) As the pointer states are the only ones able to survive decoherence, and as interactions with the environment pass information concerning the quantum state to the environment, a quantum system's environment becomes heavily imprinted with redundant copies of information concerning the quantum system's pointer states. It is these environmental copies that we actually experience and from which we gain information concerning quantum systems in almost all cases. For instance quantum systems are in continual interaction with the vast number of photons in their immediate environment. When we observe an object visually we are actually accessing information that has been imprinted on photons during previous interactions with the quantum system under observation.

4) The redundant imprinting of information in the environment makes this information available to multiple observers and provides the basis for our classical concept of objectivity or the ability of numerous observers to access and confirm the same information.

While this process may explain the emergence of classical physics from quantum physics it may not be clear where the Darwinian part comes in. Zurek explains his motivation in naming Quantum Darwinism:

Using Darwinian analogy, one might say that pointer states are most fit. They survive monitoring by the environment to leave descendants that inherit their properties. Classical domain of pointer states offers a static summary of the result of quantum decoherence. Save for classical dynamics, (almost) nothing happens to these einselected states, even though they are immersed in the environment.

Trust the reactions of your peers more

Dan Gilbert, Tim Wilson, and co-authors have found:

Two experiments revealed that (i) people can more accurately predict their affective reactions to a future event when they know how a neighbor in their social network reacted to the event than when they know about the event itself and (ii) people do not believe this. Undergraduates made more accurate predictions about their affective reactions to a 5-minute speed date (n = 25) and to a peer evaluation (n = 88) when they knew only how another undergraduate had reacted to these events than when they had information about the events themselves. Both participants and independent judges mistakenly believed that predictions based on information about the event would be more accurate than predictions based on information about how another person had reacted to it.

The link to the article is here.

Anything but the election, part II

In The Journal of Cosmology, Rhawn Joseph, Ph.D. writes:

Humans are sexual beings and it can be predicted that male and female astronauts will engage in sexual relations during a mission to Mars, leading to conflicts and pregnancies and the first baby born on the Red Planet. Non-human primate and astronaut sexual behavior is reviewed including romantic conflicts involving astronauts who flew aboard the Space Shuttle and in simulated missions to Mars, and men and women team members in the Antarctic. The possibilities of pregnancy and the effects of gravity and radiation on the testes, ovaries, menstruation, and developing fetus, including a child born on Mars, are discussed. What may lead to and how to prevent sexual conflicts, sexual violence, sexual competition, and pregnancy are detailed. Recommendations include the possibility that male and female astronauts on a mission to Mars, should fly in separate space craft.

The piece has numerous flaws, which are some mix of sad, funny, and outrageous, depending on your point of view.

Hat tip goes to The Browser.

The mimic octopus

1:49 of wow.

You can read more here about the mimic octopus.

For the pointer I thank Chris F. Masse.

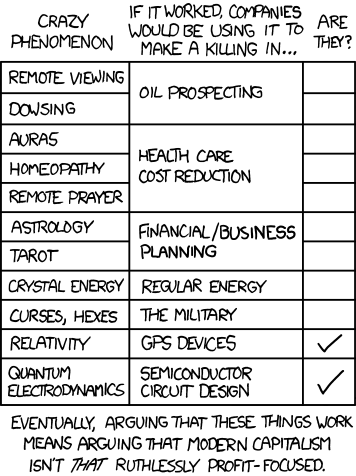

xkcd on Efficient Markets

Not to mention that there is an easy $1,000,000 lying on the sidewalk for the true practitioner of the paranormal, supernatural, or occult.

Hat tip: Brad DeLong.

Run for the Border

By perceiving state borders to be physical barriers that keep disaster at bay, people underestimate the severity of a disaster spreading from a different state, but not the severity of an equally distant disaster approaching from within a state. We call this bias in risk assessment the border bias.

More here. Amusingly, the authors show that making the border more salient by darkening the border lines on a map can make people feel even more protected.

Hat tip: Paul Kedrosky.

Benoit Mandelbrot has passed away at 85

Here are some reports, and here. He did critical work in topics such as fat tails and fractals and his stock as a thinker rose considerably after the financial crisis. Losing Allais, McKenzie, and Mandelbrot in one week is a significant decline in the number of fundamental thinkers.

Gay Sex Statistics

OKTrends has another great post, gay sex v. straight sex, analyzing data on millions of customers who use the dating site OKCupid. Here is one piece of the long post that I found surprising.

Another common myth about gay people is that they sleep around, but the statistical reality is that gay people as a group aren't any more slutty than straights.

- straight men: 6

- gay men: 6

- straight women: 6

- gay women: 6

Here's how the distribution curves compare:

- 45% of gay people have had 5 or fewer partners (vs. 44% for straights)

- 98% of gay people have had 20 or fewer partners (vs. 99% for straights)

It turns out that a tiny fraction of gays have single-handedly two-handedly created the public image of gay sexual recklessness–in fact we found that just 2% of gay people have had 23% of the total reported gay sex, which is pretty crazy.

Maurice Allais

French physicist and economic Nobel Laureate Maurice Allais has died at age 99. Allais is best known among American economists for the Allais paradox but Allais was a polymath with contributions (and JSTOR here) in a huge number of areas many of which were often overlooked because his work was not translated into english (an unfortunate fact which is still true today).

One thing that few people know about Allais was that he was a big proponent of the gold standard and Austrian business cycle theory, even citing Mises and Rothbard in some of his work. See in particular his paper in English, The Credit Mechanism and its Implications (1987) in Feiwel (ed), Arrow and the Foundations of the Theory of Economic Policy. See also here for further citations in french.

As might be expected from a polymath, Allais's views are difficult to pigeonhole. He was a strong proponent of private property and the market economy, for example, but to create the consensus necessary to produce such a society he also favored immigration restrictions and protectionism.

Amazingly, Allais also conducted ground breaking experiments on pendulums which earned him the 1959 Galabert Prize of the French Astronautical Society and which may have revealed an anomaly in general relativity that physicists refer to as the Allais effect.

How recognizable will humans be in five hundred years?

Alex reports:

Tyler and I argued recently about whether or not humans will be recognizably human in 500 years.

Let us assume that scientific progress continues. My view is that parents don't so much like "difference," unless it is very directly in their favor. Using technology, parents will select for children who are taller, smarter in the way that parents value, better looking, and perhaps also more loyal to their families. The people in the wealthy parts of the world will look more like models and movie stars, but they will be quite recognizable. These children may also be less creative and some of them will be less driven. It's a bit like the real estate market, where everyone wants their house to be special, but not too special, for purposes of resale or in this case mating and career prospects.

Assortative mating can increase the variance of appearance (and other characteristics), but a) assortative mating is not obviously a dominant effect, b) not necessarily doing much over the course of five hundred years, and c) future science is more likely to reverse the boost in variance than to support it. One short person could marry another short person, without having such short children because of genetic engineering.

People will in various ways be cyborgs, but more or less invisibly from the outside at least.

Dogs look different than they did five thousand years ago, but that is because humans controlled their breeding and opted for some extremes. How would they look today if the dogs themselves had been in charge of the process?

The Singularity is Near: Robot with Rat Brain

Tyler and I argued recently about whether or not humans will be recognizably human in 500 years. Some data is provided in this video from Wired Science and more discussion in this paper.

Perhaps most important to note is that the robot with rat brain was created by a proto-cyborg.

The pricing of in vitro fertilization

Robert G. Edwards has just won the Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on in vitro fertilization. So I searched for "economics in vitro" and found a recent paper on pricing IVF, by Anthony Dukes and Rajeev Tyagi:

This paper examines the economics of pricing practices at artificial reproductive clinics, which have introduced money-back guarantees (MBGs) for in vitro fertilization. We identify incentives for clinics to offer MBGs and evaluate the impact on couples' choices and on social welfare. Introducing MBGs allows a clinic to (i) segment couples simultaneously on their relative fertility and on risk preferences; (ii) offer quantity discounts to relatively infertile couples; and (iii) offer some risk-sharing to couples for this costly procedure, whose outcome is uncertain. Our results also show how the addition of MBGs can affect the overall social welfare.

In other words, price discrimination. (As it is applied, IVF succeeds one time out of five.) Low-fertility couples are made better off by the implied discount, some high-fertility couples may be worse off from the higher prices they face, and overall social welfare goes up from the money back guarantee, which also may signal provider quality.

Here is a recent critique, claiming that the money-back guarantee damages the nature of parenthood. Yet it is believed that four million people have been born, thanks to IVF.