Category: Uncategorized

Graduate student fellowships at George Mason/Mercatus

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University is currently accepting applications for our graduate student programs for the 2020-2021 academic year, including several graduate student fellowships for students in any discipline and from any university. The application deadline is March 15, 2020.

The Adam Smith Fellowship is a one-year, competitive program for doctoral students interested in political economy and is co-sponsored with Liberty Fund, Inc. Fellowships are awarded to students attending PhD programs from any university and in any discipline, including economics, philosophy, political science, and sociology.

The Frédéric Bastiat Fellowship is a one-year, competitive program for graduate students interested in applying political economy to pressing public policy issues. Fellowships are awarded to students attending master’s, juris doctoral, and doctoral programs at any university and in any discipline, including economics, law, political science, and public policy.

The Oskar Morgenstern Fellowship is a one-year, competitive fellowship program awarded to doctoral students with training in quantitative methods who interested in applying these methods to issues in political economy. Fellowships are awarded to students attending PhD programs from any university and in any discipline, including economics, political science, and sociology.

Here is the overall fellowships page.

Thursday assorted links

1. A Bayesian approach to Bernie Sanders (show your work).

2. Should libertarians ally with Bolsonaro?

3. In which I interview Tom Kalil, Chief Innovation Officer at Schmidt Futures (other sessions too, scroll down for mine). And Phantom Tyler says solve for the equilibrium.

4. New British fast-track visa, aimed especially at scientists.

5. Taste for Indian food predicts Bernie Sanders support (NYT). But what does an interest in Pakistani food correlate with? In the United States, Pakistani food usually is better than Indian.

6. “A professor at one of China’s top universities has quit what many academics would regard as a dream job after he gained celebrity status through an online “knowledge-sharing” platform.” (former GMU student, 2008 Ph.d)

The vaccine makers have solved for the equilibrium

GSK has made a corporate decision that while it wants to help in public health emergencies, it cannot continue to do so in the way it has in the past. Sanofi Pasteur has said its attempt to respond to Zika has served only to mar the company’s reputation. Merck has said while it is committed to getting its Ebola vaccine across the finish line it will not try to develop a vaccine that protects against other strains of Ebola and the related Marburg virus.

Drug makers “have very clearly articulated that … the current way of approaching this — to call them during an emergency and demand that they do this and that they reallocate resources, disrupt their daily operations in order to respond to these events — is completely unsustainable,” said Richard Hatchett, CEO of CEPI, an organization set up after the Ebola crisis to fund early-stage development of vaccines to protect against emerging disease threats.

Hatchett and others who plan for disease emergencies worry that, without the involvement of these types of companies, there will be no emergency response vaccines.

Here is more from Helen Branswell, you can follow her on Twitter here on the evolving coronavirus situation, she is maybe the single best follow on that topic?

What I’ve been reading

Randy Shaw, Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America. A YIMBY book, with good historical material on San Francisco, Los Angeles, and other locales involved in the struggle to build more.

Conor Daugherty, Golden Gates: Fighting for Housing in America. Coming out in February, this is a very good book about the YIMBY movement and its struggles, with a focus on contemporary California, written by a NYT correspondent.

Jennifer Delton, The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American Capitalism. Why don’t more books fit this model: take one topic and explain it well?

Economists, Photographs by Mariana Cook, edited with an introduction by Robert M. Solow. Self-recommending. Interestingly, I recall an old University of Chicago calendar of economist photographs, still buried in my office somewhere, with pictures of Frank Hyneman Knight, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, and others. At least in terms of personality types, as might be revealed through photographs, the older collection seems to me far more diverse. Or is the homogenization instead only in terms of photograph poses?

Michael E. O’Hanlon, The Senkaku Paradox: Risking Great Power War Over Small Stakes. A very useful practical book about what options a U.S. government would have — short of full war — to deal with international grabs by China or Russia. There should be thirty more books on this topic (#ProgressStudies).

Christopher Caldwell, The Age of Entitlement: America Since the Sixties. This is both a very old thesis, but these days quite new, namely the claim that 1965 and the Civil Rights movement created a “new constitution” for America, at variance with the old, and the two constitutions have been at war with each other ever since. It will be one of the influential books “on the Right” this year, I already linked to this Park MacDougald review of the book.

Robert H. Frank, Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work. From the Princeton University Press catalog: “Psychologists have long understood that social environments profoundly shape our behavior, sometimes for the better, often for the worse. But social influence is a two-way street—our environments are themselves products of our behavior. Under the Influence explains how to unlock the latent power of social context. It reveals how our environments encourage smoking, bullying, tax cheating, sexual predation, problem drinking, and wasteful energy use. We are building bigger houses, driving heavier cars, and engaging in a host of other activities that threaten the planet—mainly because that’s what friends and neighbors do.”

Wednesday assorted links

1. Those who advertise for those new service sector jobs.

2. The Discourse Initiative — a new support program from the Institute for Humane Studies.

3. Most influential books for Salim Furth.

4. Jerry Falwell Jr. favors Vexit.

My Conversation with Ezra Klein

Here is the audio and transcript. Yes we talked a great deal about Ezra’s new book on polarization, but much more too:

Tyler posed these questions to Ezra and more, including thoughts on Silicon Valley’s intellectual culture, his disagreement with Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory, the limits of telecommuting, how becoming a father made him less conservative, his post-kid production function, why Manhattan is overrated, the “cosmic embarrassment” of California’s governance, why he loved Marriage Story, the future of the BBC and PBS, what he learned in Pakistan, and more.

Here is one bit:

COWEN: We would agree that what is called affective negative polarization is way up — professing a dislike of the other side, not wanting your Republican kid to marry a Democratic wife, and so on. But in terms of actual policy polarization, what if someone says, “Well, that’s down,” and they say this: “Well, the main issue in foreign policy today is China.” That’s actually fairly bipartisan. Or if people don’t agree, they don’t disagree by party.

Domestic spending, Social Security, Medicare — no one wants to cut those. That’s actually consensus. The other main issue is how we deal with or regulate tech. America has its own system. It’s happened through the regulators. It’s not really that partisan. One may or may not like it, but again, disagreement about it doesn’t fall along normal party lines.

So the main foreign policy issue, the main substantive social issue — we’re less polarized. And then, domestic spending, it seems, we all mostly agree. Why is that wrong?

KLEIN: I’m not sure it is wrong. Two things I would say about it. One, the word main is doing a lot of work in that argument. The question is, how do you decide what are the main issues? I wouldn’t say domestic regulation of tech is a main issue, for instance. I think it’s important, but compared to things like immigration and healthcare, at least in the way people experience that and think about that — or if you ask them what are their main issues, domestic regulation of tech doesn’t crack the top 10.

And:

COWEN: But again, at any point in time, if positions are shifting rapidly — as they are, say, on trade — if you took all of GDP, even healthcare — that’s what, maybe 18 percent of GDP? But a lot of the system, a lot of people in both parties agree on, even if they disagree on Obamacare. Obamacare is part of that 18 percent. Over what percent of GDP are we more polarized than we used to be, as compared to less polarized? What’s your estimate?

KLEIN: I like that question. Let me try to think about this. I don’t think I have a GDP answer for you, but let me try to give you more of what I think of as a mechanism.

I think a useful heuristic here — people don’t have nearly as strong views on policy qua policy as certainly people like you and I tend to assume they do. The way that Washington, DC, talks about politics is incredibly projection oriented. We talk about politics as if everybody is a political junkie with highly distinct ideologies.

Political scientists have done a lot of polling on this, going all the way back to the 1960s, and it seems something like 20 to 30 percent of the population has what we would think of as a coherent policy-oriented ideology, where things fit together, and they have everything lined up. Most people don’t hold policy positions all that strongly.

What happens is that they do hold — to the extent they’re involved in politics — identity strongly, political affiliations quite strongly. They know who is on their side and who isn’t.

The pattern that I see here, again and again, is that when things are out of the spotlight, when they are not being argued about, when they are not the thing that the parties are disagreeing about, they’re actually quite nonpolarized. You’ll sit there in rooms of experts. There’ll be a panel here, George Mason, whatever it might be, and everybody will have some good ideas about how you can make the system better for everyone.

Then what will happen is, the Eye of Sauron of the American political system will turn towards whatever the policy issue is. Maybe it’s Obamacare, maybe it’s climate change. Remember, climate change was not that polarized 15–20 years ago. John McCain had a big cap-and-trade plan in his 2008 platform —

And:

COWEN: If you could engineer your own political temperament, would you change it from how it is? Mostly, we’re stuck with what we’ve got, I would say, but if you could press the button — more passionate, less passionate, something else? Goldilocks?

KLEIN: I think I like my political temperament. Probably for the era of politics we’re moving into, and for my job, it would almost be better to be of a more conflict-oriented temperament than I am. I think that we are moving into something that, at least in the short term, is rewarding or is going to reward those who really like getting in fights all the time, and I don’t like that.

I’m more consensus oriented. I like hearing people out. I probably have a little bit more of a moderate temperament in that way. But I wouldn’t really change that about myself. I think it’s a shame that so much of politics happens on Twitter now, but that’s the way it is. I wouldn’t change me to operate to that.

Recommended, and again here is Ezra’s new book on polarization.

Draining the swamp

From Jason Crawford, Emergent Ventures winner in Progress Studies:

…the surprising thing I found is that infectious disease mortality rates have been declining steadily since long before vaccines or antibiotics…

In 1900, the most deaths came from tuberculosis, influenza/pneumonia, and gastroenteric diseases such as dysentery. All of these were effectively conquered by antibiotics in the 1930s and ’40s, but were on the decline since at least the beginning of the century…

Indeed, digging further into the UK data from the late 1800s, we can see that TB was declining since at least 1850 and gastroenteric disease since the 1870s. And similar patterns hold for lesser killers such as measles, which didn’t have a vaccine until the 1960s, but which by then had already declined in mortality by more than 90% from its 1900 levels.

So what was going on? If you read my survey of technologies against infectious disease, you know that other than drugs and immunization, there is one other way to fight germs: cleaning up the environment.

I was surprised to learn that sanitation efforts began as early as the 1700s—and that these efforts were based on data collection and analysis, long before a full scientific theory of infection had been worked out.

There is much more at the link, including the footnotes for citations to the claims made here.

Tuesday assorted links

Daniel Gross on productivity

The longer you think about a task without doing it, the less novel it becomes to do. Writing things in your to-do list and coming back to them later helps you focus, but it comes at the cost: you’ve now converted an interesting idea into work. Since you’ve thought about it a little bit, it’s less interesting to work on.

It’s like chewing on a fresh piece of gum, immediately sticking it somewhere, then trying to convince yourself to rehydrate the dry, bland, task of chewed-up gum. Oh. That thing. Do you really want to go back to that? “We’ve already gone through all the interesting aspects of that problem, and established that there’s only work left”, the mind says.

Stateless Browser

One day someone will make a to-do product that lets you serialize and deserialize flow, like protobuf. Until then, my solution is to (somewhat counter-intuitively) not think about the task until I am ready to fully execute it. I do not unwrap the piece of gum until I’m ready to enjoy it in its entirety. I need to save the fun of thinking to pull myself into flow.

- I try and respond to emails the moment I open them. If it’s something that requires desktop work, I quickly close the email.

- I don’t write down ideas for posts until I’m ready to write the entire post.

- I write down a few bullets of what I need out of a meeting, and then refuse to think about it until the actual event.

There are many more points at the link. My classic line is simply “I’m not going to focus on that right now.”

Gabriel Tarde’s *On Communication and Social Influence*

This 19th century French sociologist is worth reading, as he is somehow the way station between Pascal and Rene Girard, with an influence on Bruno Latour as well. Tarde focuses on how copying helps to explain social order and also how it drives innovation. For Tarde, copying, innovation, and ethos are all part of an integrated vision. He covers polarization and globalization as well and at times it feels like he has spent time on Twitter.

It is hard to pull his sentences out of their broader context but here is one:

We have seen that the true, basic sources of power are propagated discoveries or inventions.

And:

The role of impulse and chance in the direction of inventive activity will cease to amaze us if we recall that such genius almost always begins in the service of a game or is dependent on a religious idea or superstition.

Or:

…contrary to the normal state of affairs, images in the inventor’s hallucinatory reverie tend to become strong states while sensations become weak states.

…When the self is absorbed in a goal for a long time, it is rare that the sub-self, incorrectly called the unconscious, does not participate in this obsession, conspiring with our consciousness and collaborating in our mental effort. This conspiracy, this collaboration whose service is faithful yet hidden, is inspiration…

He argues that societies in their uninventive phase are also largely uncritical, and for that reason. (Doesn’t that sound like a point from a Peter Thiel talk?)

He explicitly considers the possibility that the rate of scientific innovation may decline, in part because the austere and moral mentality of semi-rural family life, which is most favorable for creativity in his view, may be replaced by the whirlpool of distractions associated with the urban lifestyles of the modern age.

And:

Attentive crowds are those who crowd around the pulpit of a preacher or lecturer, a lectern, a platform, or in front of the stage where a moving drama is being performed. Their attention — and inattention — is always stronger and more constant than would be that of the individual in the group if he were alone.

Tarde argues that desires are intrinsically heterogeneous, and economics makes the mistake of reducing them to a near-tautologous “desire for wealth.”

Not all of it hangs together, but I would rather read Tarde than Durkheim or Comte, the other two renowned French sociologists of the 19th century.

You can buy the book here, here is Wikipedia on Tarde.

Monday assorted links

My chat with Brendan Fitzgerald Wallace

He interviewed me, here is his description: “My conversation with economist, author & podcaster Tyler Cowen covering everything from: 1) Buying Land on Mars (for real) 2) Privatizing National Parks 3) Setting up aerial highways in the sky for drone delivery 4) Buying Greenland 5) London post Brexit 6) Universal Basic Income 7) Why Los Angeles is “probably the best city in North America” 8) How real estate can combat social isolation & loneliness 9) Cyber attacks on real estate assets and national security implications. 10) The impacts, positive and negative of Climate Change, on real estate in different geographies. 11) Other esoteric stuff…..”.

Here is the conversation, held in Marina del Rey at a Fifth Wall event.

Evidence for State Capacity Libertarianism

The plots do not support the hypothesis that small government produces either greater prosperity or greater freedom. (In reading the charts, remember that the SGOV index is constructed so that 0 indicates the largest government and 10 the smallest government.) Instead, smaller government tends to be associated with less prosperity and less freedom. Both relationships are statistically significant, with correlations of 0.43 for prosperity and 0.35 for freedom.

Using SoG, the Cato measure of size of government, instead of SGOV, the IMF measure, does not help. The correlations turn out still to be negative and statistically significant, although slightly weaker.

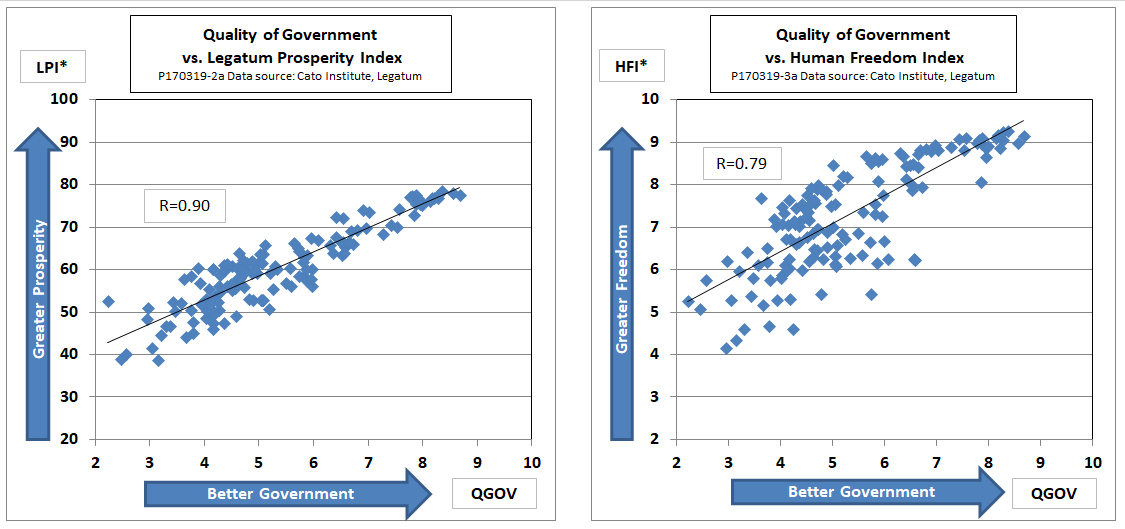

Let’s turn now to the alternative hypothesis that quality of government, rather than size, is what counts for prosperity and freedom. Here are those scatterplots:

This time, both relationships are positive. High quality of government is strongly associated both with greater human prosperity and greater human freedom. Furthermore, the correlations are much stronger than those for the size of government.

That is all by Ed Dolan, recommended, and by the way smaller governments are not correlated with higher quality governments.

Sunday assorted links

3. MIE: meat cleaver massage.

Coronavirus information and analysis bleg

What are the best things to read to estimate what’s going to happen from here?

In particular, what is the best way to think about how to make inferences, or not, from extrapolating current trends about case and death numbers?

What is “what happens from here” going to be most sensitive to in terms of potential best remedies? Regulatory decisions of some kind? Which features of local public health infrastructure will matter the most? Will any of it matter at all?

Which variables should we focus on to best predict expected severity?