When does a Bitcoin reserve make sense?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Now enter Bitcoin. Senator Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming has introduced a bill to have the Treasury create a $67 billion (at current value) stockpile of the cryptocurrency, and Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump supports the idea, saying it would be “a permanent national asset to benefit all Americans.” The bill may not be a serious piece of legislation — it is highly unlikely to pass — but it raises a serious question: Under what circumstances can governmental purchases of cryptocurrency be justified?

And:

To see one version of the case for government purchases of Bitcoin, consider Argentina, where past hyperinflation has made both dollars and Bitcoin very popular. Inflation rates are declining under President Javier Milei, but Argentina’s currency future will probably still feature both currencies. Milei even suggested as much recently.

El Salvador is another case in point. The country already is fully dollarized, and President Nayib Bukele has been taking steps to encourage crypto use and investment. So far his intended crypto revolution has not taken off, but the country does offer highly favorable terms for crypto users and investors. If crypto rises in importance, some of that financial activity may take place in El Salvador, if only for regulatory reasons.

In short, there might be a number of governments that use dollars and crypto as a significant part of their natural monetary base, along with the domestic currency (if it still exists). In fact, the more dollarization spreads, the more the demand for crypto and Bitcoin may rise.

Many countries are aware of the advantages to using the dollar, but they may also come to see crypto as a useful tool that weakens the ability of the US government to apply financial sanctions. The end result may be more dollarization — but with crypto as a complementary back-up financial system. Crypto also could give those countries more elastic money supplies, in case they find Fed policy too tight for their economy.

To bring it back to domestic US concerns: If crypto and the dollar are complements internationally, the US government might want to encourage crypto as a way to expand the reach of the dollar. The dollar truly would become further entrenched as the global reserve currency, boosting possible levels of US consumption.

But not yet.

The new Raj Chetty paper on changes in opportunity

Here is the paper, with co-authors Will Dobbie, Benjamin Goldman, Sonya R. Porter, and Crystal S. Yang. Here is the abstract:

We show that intergenerational mobility changed rapidly by race and class in recent decades and use these trends to study the causal mechanisms underlying changes in economic mobility. For white children in the U.S. born between 1978 and 1992, earnings increased for children from high-income families but decreased for children from low-income families, increasing earnings gaps by parental income (“class”) by 30%. Earnings increased for Black children at all parental income levels, reducing whiteBlack earnings gaps for children from low-income families by 30%. Class gaps grew and race gaps shrank similarly for non-monetary outcomes such as educational attainment, standardized test scores, and mortality rates. Using a quasi-experimental design, we show that the divergent trends in economic mobility were caused by differential changes in childhood environments, as proxied by parental employment rates, within local communities defined by race, class, and childhood county. Outcomes improve across birth cohorts for children who grow up in communities with increasing parental employment rates, with larger effects for children who move to such communities at younger ages. Children’s outcomes are most strongly related to the parental employment rates of peers they are more likely to interact with, such as those in their own birth cohort, suggesting that the relationship between children’s outcomes and parental employment rates is mediated by social interaction [emphasis added]. Our findings imply that community-level changes in one generation can propagate to the next generation and thereby generate rapid changes in economic mobility.

Here is NYT coverage, here is WSJ coverage.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Wolfgang Rihm, RIP (NYT).

2. Maduro at 82% to “win,” Polymarket puts this “under review,” however.

3. Fairfax County data center NIMBY uh-oh.

4. Higher inflation comes to Japan (NYT),

5. Rorschach test El Salvador prison video, interesting.

6. Thomas Sargent joins Cato as a visiting scholar.

7. Friend.com

Underreported news of the day

The attack affected online services of all major Russian banks, national payment systems, social networks and messengers, government resources, and dozens of other services…Carpet-Bombing Hack: #Ukraine’s Intelligence (#HUR) has completed one of the largest cyberattacks on Russia’s financial sector and government resources, Kyiv Post HUR sources reported.

Here is the link.

Cowen’s Third Law, illustrated

We further show that demographic and productivity factors do not represent convincing drivers of real interest rates over long spans.

That is from a new AER piece by Kenneth S. Rogoff, Barbara Rossi, and Paul Schmelzing. Here are less gated copies of the piece. Here are some MR posts on Cowen’s Third Law.

Are higher wages in wartime just capital consumption?

In the Austrian-Hungarian Empire during World War I:

In order to obtain the required manpower, the armaments manufacturers began to pay their workers higher wages. This had an almost instant impact on other businesses and firms, which could not compete with the wages of the armaments industry and were thus unable to find any workers. In the Wöllersdorf armaments factory, for example, the number of male workers increased five-fold from August to the end of December 1914, but a construction firm that was suppposed to build new aircraft engine hangars had to appeal to the War Ministry because it could no longer find any workers.

That is from p.202 of Manfried Rauchensteiner, The First World War and the End of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1914-1918. That is by the way an excellent book, gripping throughout despite its length.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is a very good movie. Romanian, bizarre, funny.

3. How price elastic is charitable giving?

4. Claims correlated with dark oxygen claims.

5. The Brain Book (for children). Supports the Albanian language too.

Venezuela under “Brutal Capitalism”

Jeffrey Clemens points us to some bonkers editorializing in the NYTimes coverage of the likely stolen election in Venezuela. The piece starts out reasonably enough:

Venezuela’s authoritarian leader, Nicolás Maduro, was declared the winner of the country’s tumultuous presidential election early Monday, despite enormous momentum from an opposition movement that had been convinced this was the year it would oust Mr. Maduro’s socialist-inspired party.

The vote was riddled with irregularities, and citizens were angrily protesting the government’s actions at voting centers even as the results were announced.

The term “socialist-inspired party” is peculiar. The party in question is the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela) and it’s founding principles state, “The party is constituted as a socialist party, and affirms that a socialist society is the only alternative to overcome the capitalist system.” So, I would have gone with ‘Mr. Maduro’s socialist party’. No matter, that’s not the big blunder. Later the piece says:

If the election decision holds and Mr. Maduro remains in power, he will carry Chavismo, the country’s socialist-inspired movement, into its third decade in Venezuela. Founded by former President Hugo Chávez, Mr. Maduro’s mentor, the movement initially promised to lift millions out of poverty.

For a time it did. But in recent years, the socialist model has given way to brutal capitalism, economists say, with a small state-connected minority controlling much of the nation’s wealth.

Venezuela is now governed by “brutal capitalism” under Maduro’s United Socialist Party!??? The NYTimes has lost touch with reality. From the link we find that what they mean is that some price and wage controls were lifted, including allowing dollars to be used because the bolívar, was “made worthless by hyperinflation,” and remittances from the United States were legalized:

NYTimes: With the country’s economy derailed by years of mismanagement and corruption, then pushed to the brink of collapse by American sanctions, Mr. Maduro was forced to relax the economic restraints that once defined his socialist government and provided the foundation for his political legitimacy.

Lifting some controls does not make Venezuela a capitalist country. Moreover, the lifting of controls led to improvements:

…Seeing shelves stocked again has also helped ease tensions in the capital, where anger over the lack of basic necessities has, over the years, helped fuel mass protests.

…The transformation also brought some relief to the millions of Venezuelans who have family abroad and can now receive, and spend, their dollar remittances on imported food.

Of course, the improvements were not equally shared. If you want to call unequal improvements, “brutal capitalism”. Well, I don’t think that’s useful but if you do so be sure to note that “under Maduro’s administration, more than 20,000 people have been subject to extrajudicial killings and seven million Venezuelans have been forced to flee the country.” (Wikipedia.) That’s brutal socialism.

Lastly, I don’t expect, the NYTimes to keep up on the latest counter-factual estimation techniques so I won’t ding them too much, but it’s clear that the Chavismo regime never lifted millions out of poverty. At best, poverty fell during the good years at the rate one would have expected from looking at similar countries. It’s the later rise in poverty which is unprecedented, as the NYTimes previously acknowledged.

Britain fact of the day

But many of the phrases the English grew up with are fading away as younger generations plug into TikTok or other platforms where they learn to call each other “Karen” or “basic” like any other rando, instead of sticking with tried and tested indigenous slurs.

Nearly 60% of the Gen Z cohort haven’t heard the insult “lummox,” according to a study by research agency Perspectus Global. Less than half know what a “ninny” is, with only slightly more of them familiar with “prat” or “tosspot.”

What a bunch of plonkers.

There was a time when nearly everybody would sling about terms like “blighter” or “toe-rag,” and sometimes far ruder terms. That was when the British had more of a shared pop culture, often built around television comedies such as “Only Fools and Horses,” about a family of likable London con men. People would talk about them in the schoolyard or at work the next morning. Everyone knew what everyone else was talking about, even if it was a load of twaddle.

Here is more from James Hookway at the WSJ. How can those ninnies not know what a ninny is?

Global warming, and rate effects vs. level effects

There is a very interesting new paper on this topic byIshan B. Nath, Valerie A. Ramey, and Peter J. Klenow. Here is the abstract:

Does a permanent rise in temperature decrease the level or growth rate of GDP in affected countries? Differing answers to this question lead prominent estimates of climate damages to diverge by an order of magnitude. This paper combines indirect evidence on economic growth with new empirical estimates of the dynamic effects of temperature on GDP to argue that warming has persistent, but not permanent, effects on growth. We start by presenting a range of evidence that technology flows tether country growth rates together, preventing temperature changes from causing growth rates to diverge permanently. We then use data from a panel of countries to show that temperature shocks have large and persistent effects on GDP, driven in part by persistence in temperature itself. These estimates imply projected future impacts that are three to five times larger than level effect estimates and two to four times smaller than permanent growth effect estimates, with larger discrepancies for initially hot and cold countries.

Here is one key part of the intuition:

We present a range of evidence that global growth is tied together across countries, which suggests that country-specific shocks are unlikely to cause permanent changes in country-level growth rates…Relatedly, we find that differences in levels of income across countries persist strongly, while growth differences tend to be transitory.

Another way to make the point is that one’s model of the process should be consistent with a pre-carbon explosion model of income differences (have you ever seen those media articles about how heat from climate change supposedly is making us stupider, with no thought as to further possible implications of that result? Mood affiliation at work there, of course).

After the authors go through all of their final calculations, 3.7 degrees Centigrade of warming reduces global gdp by 7 to 12 percent by 2099, relative to no warming at all. For sub-Saharan Africa, gdp falls by 21 percent, but for Europe gdp rises by 0.6 percent, again by 2099.

The authors also work through just how sensitive the results are to what is a level effect and what is a growth effect. For instance, if a warmer Europe leads to a permanent growth-effect projection, Europe would see a near-doubling of income, compared to the no warming scenario. The reduction in African gdp would be 88 percent, not just 21 percent.

By the way, the authors suggest the growth bliss point for a country (rat’ mal!) is thirteen degrees Centigrade.

This paper has many distinct moving parts, and thus it is difficult to pin down what is exactly the right answer, a point the authors stress rather than try to hide. In any case it represents a major advance of thought in this very difficult area.

What should I ask Tom Tugendhat?

My previously scheduled Conversation with him was postponed, now it is on the schedule again. So what should I ask him? (Wikipedia page here, if you don’t know what a lummox is).

Not the worst news…

We find that markups increased by about 30 percent on average over the sample period. The change is primarily attributable to decreases in marginal costs, as real prices only increased slightly from 2006 to 2019. Our estimates indicate that consumers have become less price sensitive over time.

That is from a new NBER working paper by

…the empirical evidence relating to concentration trends, markup trends, and the effects of mergers does not actually show a widespread decline in competition. Nor does it provide a basis for dramatic changes in antitrust policy. To the contrary, in many respects the evidence indicates that the observed changes in many industries are likely to reflect competition in action.

Rooftops, people…

Monday assorted links

1. Bukele and the future of El Salvador. A good piece, though I don’t agree with everything in there.

2. The Ohio Supreme Court vs. Aristotle?

3. History of early American tariffs.

4. Some new estimates of what people really enjoy.

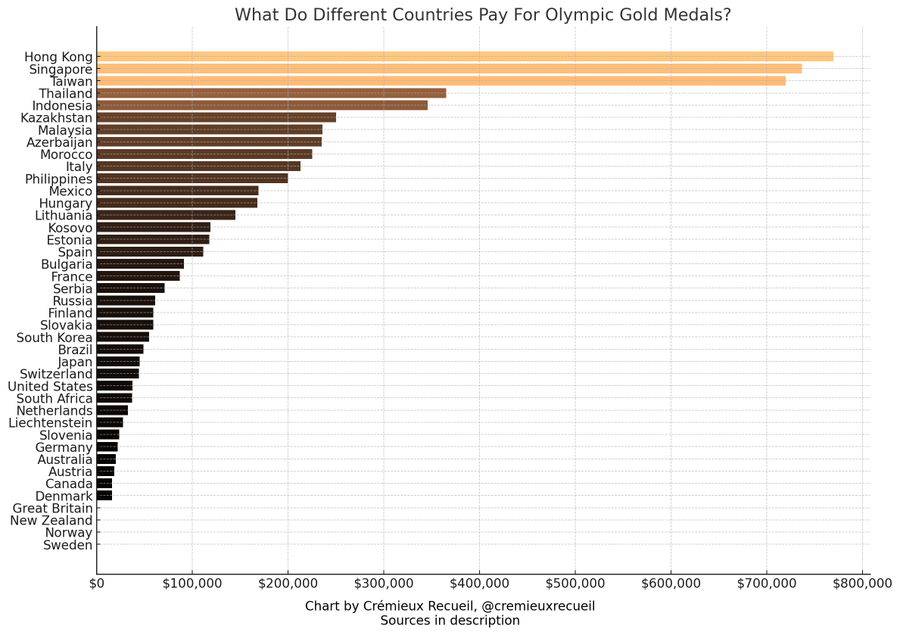

What do different countries pay for Olympic gold medals?

Via Cremieux, and here is the related Wikipedia page.

What are Republican analysts getting wrong about free trade?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

It is true that 19th century tariffs often were high, but they were not the main reason the US became rich (they were an important means of funding the government, given the absence of an income tax). The best economic research shows that what drove US economic growth was population expansion and capital accumulation. Tariffs raised the price of imported capital goods and thus partially discouraged growth, while the US expansion was actually most rapid in non-tradeable goods.

That is Doug Irwin of course. And this:

The US might end subsidizing its domestic drone sector, for example, given the military importance of those devices. But there are limits to how many sectors the US can support or protect. Looking at some of the successes abroad, it is clear that those manufacturing jobs are often very high status and relatively well paid. They attract some of the best talent, as do chip factories in Taiwan or Korea. The US could benefit from reallocating some efforts to defense and defense-related sectors — but it can’t achieve everything all at once. Instead, it needs to prioritize where to put its best talent.

In some cases there is reason to be concerned, for instance by the decline of Boeing, which if anything has been protected too long by its reliance on government as a major customer. Industrial policy or government protections don’t automatically bring quality or commercial success.

And finally:

- Most economists, whether on the left or right, still support free trade.

With national security qualifications, as noted above. Expertise really does matter, and the US has a lot of expertise in free trade. For all the sneering at rarified concepts such as “neoliberalism,” critics of free trade have no new arguments that economists have not already rebutted. And if Republicans are not going to respect expertise in this matter, do you really think they will follow the best available advice in setting up tariffs and industrial policy?

Recommended, interesting throughout.