The Austerity Flip-Flop

On April 28, 2013 Paul Krugman clearly said that 2013 was a test of market monetarism:

But as Mike Konczal points out, we are in effect getting a test of the market monetarist view right now, with the Fed having adopted more expansionary policies even as fiscal policy tightens.

Yesterday (Jan 4, 2014) however, Paul Krugman, said:

…I don’t take seriously the claims of market monetarists that the failure of growth to collapse in 2013 somehow showed that fiscal policy doesn’t matter.

There are two obfuscations here. First, it wasn’t the market monetarists who established the test it was Konczal and Krugman who laid down the glove so Krugman is saying he doesn’t take his own (April) claims seriously. Second, in April Krugman did appear to take his claims seriously, perhaps because:

…the results aren’t looking good for the monetarists: despite the Fed’s fairly dramatic changes in both policy and policy announcements, austerity seems to be taking its toll.

Now that the results are in, however, Paul claims that compared to southern Europe American austerity wasn’t so bad or it was really bad but small enough to be offset by “other stuff”:

US austerity, although a really bad thing, wasn’t nearly as intense as what happened in southern Europe; it was small enough that it could be, and I’d argue was, more or less offset by other stuff over the course of a single year.

But the ticker tape (April 27, 2013) suggests a much different emphasis (note also that here Paul names “other stuff’ and it is adding to the problem not subtracting):

There is some tendency among economic commentators to think that austerity policies in a deeply depressed economy are mainly a European thing… But the truth is that federal stimulus is years behind us, while state and local governments have cut back, so the overall story is one of fiscal contraction that’s smaller than in Europe, but not by that much….Bear in mind that in the years since the recession began we’ve seen a significant number of boomers reach retirement age, which would ordinarily have led to rising spending, not to mention the effects of rising health care costs. Bear in mind also that the private sector is still deleveraging, which means that government should be spending more to help sustain the economy. So this is actually a picture of very bad policy.

Even more amusingly, arch-Keynesian Paul Krugman now says we are approaching the long run! In a post titled What A Good Year Won’t Prove he says:

If 2014 is a year of relatively good growth, you know that many people will take that as somehow refuting Keynesianism — hey, didn’t you guys predict that the economy would never recover without fiscal stimulus?

No, we didn’t [the linked post, is from 2009, AT]

In the long run, we will have a spontaneous economic recovery, even if all current policy initiatives fail….

Now, to be fair, I happen to agree with Krugman that one test is not decisive. The economy is very complex and we don’t have controlled macro-experiments so lots of things are going on at the same time. But as one wise commentator put it:

…using hedged language doesn’t insulate you from consequences if things don’t turn out the way you were clearly suggesting they would, nor does the true point that sometimes the right model makes a wrong prediction. If your model led you to believe that

inflationausterity was a “great danger” in20092013 the fact that this danger never came to pass should substantially reduce your belief in that model – and should substantially reduce your credibility if you refuse to revise your beliefs.

Addendum: Scott Sumner has a similar reaction at Econlog.

Fertility decisions and the escape from slavery

Hope really does matter, as outlined in a recent paper (pdf) by Treb Allen of Northwestern, with the formal title “The Promise of Freedom”:

This paper examines the extent to which the fertility of enslaved women was affected by the promise of freedom. Because women derived greater pleasure from children when they were free, increases in the distance to freedom (which lowered the probability of escape) should reduce fertility. Exploiting the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and the particularity of U.S. geography, I demonstrate a strong negative correlation between fertility and the distance to freedom. This negative correlation is stronger on larger plantations, but disappears when the father of the child is white. The correlation varies with the difficulty of the route, and a similar correlation is not present for white children or for slave children born prior to the Fugitive Slave Law. The negative correlation suggests that despite the small number of successful escapes, the promise of freedom played an important role in the everyday lives of slaves.

There are more interesting papers by Allen here., including on the gravity equation and location theory. Allen is one of the most interesting young economists today, yet he remains undercovered. Here is Treb on “Equilibrium distribution of population if the surface of the world was shaped like a cow.”

How the job of policeman is changing

Here is one bit from an interesting article:

Minnesota has long led the nation in peace officer standards; it’s the only state to require a two-year degree and licensing. Now, a four-year degree is becoming a more common standard for entry into departments including Columbia Heights, Edina and Burnsville. Many other departments require a four-year degree for promotion.

It’s not a rapid-fire change, but rather an evolution sped up by high unemployment that deepened the candidate pool and gave chiefs more choices. Officer pay and benefits can attract four-year candidates. Edina pays top-level officers $80,000; Columbia Heights pays nearly $75,000.

Nowadays, officers are expected to juggle a variety of tasks and that takes more education, chiefs said. Officers communicate with the public, solve problems, navigate different cultures, use computers, radios and other technology while on the move, and make split-second decisions about use of force with a variety of high-tech tools on their belt. And many of those decisions are recorded by squad car dashboard cameras, officer body cameras and even bystanders with smartphones.

There is more here, and for the pointer I thank Kirk Jeffrey.

*Think Like a Freak*

That is the new forthcoming Levitt and Dubner book, due out May 13.

It is noted in this Guardian article, on which new books we can expect in 2014.

Where in the United States are the largest shadow economies?

US shadow economies: A state-level study

Travis Wiseman

Constitutional Political Economy, December 2013, Pages 310-335Abstract:

Recent studies of shadow economies focus primarily on cross-country comparisons. Few have examined regional or state-level variations in underground economic activity. This paper presents estimates of the shadow economy for 50 US states over the period 1997-2008. Results suggest that tax and social welfare burdens, labor market regulations, and intensity of regulation enforcement are important determinants of the underground economy. Among the states, Delaware, on average, maintains the smallest shadow economy at 7.28 % of GDP; Oregon, on average, has the second smallest shadow economy at 7.41 % of GDP; followed by Colorado, averaging 7.52 % of GDP, rounding out the three smallest shadow economies in the US West Virginia and Mississippi, on average, have the largest shadow economies in the US as a percent of GDP (9.32 and 9.54 %, respectively).

There are (gated?) versions of the paper here. For the pointer I thank Rob Raffety who I believe in turn is relying on Kevin Lewis. This pdf, by the way, offers data on the generally larger shadow economies of Europe.

Assorted links

1. Management lessons at Netflix? And here is Felix Salmon’s great piece on the dumbing down of Netflix.

2. Andrew Flowers at the Atlanta Fed on whether productivity has declined (pdf).

3. Some new results on whether Medicaid benefits the health of recipients (pdf).

4. Fill out this form to start your very own Altcoin.

Claudia Goldin on the gender pay gap

The pdf of her Philadelphia paper is here. This is from the concluding section:

The reasoning of this essay is as follows. A gender gap in earnings exists today that greatly expands with age, to some point, and differs significantly by occupation. The gap is much lower than it had once been and the decline has been largely due to an increase in the productive human capital of women relative to men. Education at all levels increased for women relative to men and the fields that women pursue in college and beyond shifted to the more remunerative and career-oriented ones. Job experience of women also expanded with increased labor force participation. The portion of the difference in earnings by gender that was once due to differences in productive characteristics has largely been eliminated.

What, then, is the cause of the remaining pay gap? Quite simply the gap exists because hours of work in many occupations are worth more when given at particular moments and when the hours are more continuous. That is, in many occupations earnings have a nonlinear relationship with respect to hours. A flexible schedule comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, finance and legal worlds.

A compensating differentials model explains wage differences by the costs of flexibility. The framework developed here shows why there are higher or lower costs of time flexibility and the underlying causes of nonlinearity of earnings with respect to time worked. Much has to do with the presence of good substitutes for individual workers when there are sufficiently low transactions costs of relaying information. Evidence from O*Net on occupational characteristics demonstrates that certain features of occupations that create time demands and reduce the degree of substitution across workers are associated with larger gender gaps.

Data for MBAs and JDs shows large increases in gender pay gaps with time since degree and also reveals the relationship between the increasing gender pay gap and the desire for time flexibility due to the arrival of children. Lower hours mean lower earnings in a nonlinear fashion. Lower potential earnings, particularly among those with higher-earning spouses, often means lower labor force participation. Pharmacists, on the other hand, have pay that is more linear with respect to hours of work. Female pharmacists with children often work part-time and remain in the labor force rather than exiting.

The paper is interesting throughout.

Addendum: Mary Ann Bronson, a job candidate from UCLA, has a new and interesting paper (pdf) on the gender gap across college majors and related issues. Here is another UCLA job market paper, by Gabriela Rubio, on why arranged marriages decline in frequency. This year, at Duke University, there are more female entering students in the Ph.d. program than male.

Arrived in my pile

1. Lars Peter Hansen and Thomas Sargent, Recursive Models of Dynamic Linear Economies.

2. Alberto Simpser, Why Governments and Parties Manipulate Elections.

3. Glenn Reynolds, The New School: How the Information Age Will Save American Education from Itself.

Cihan Artunç is studying legal pluralism in the Ottoman Empire

Here is the abstract from his job market paper, he is from Yale:

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, non-Muslim Ottomans paid large sums to acquire access to European law. These protégés came to dominate Ottoman trade and pushed Muslims and Europeans out of commerce. At the same time, the Ottoman firm remained primarily a small, family enterprise. The literature argues that Islamic law is the culprit. However, adopting European law failed to improve economic outcomes. This paper shows that the co-existence of multiple legal systems, “legal pluralism,” explains key questions in Ottoman economic history. I develop a bilateral trade model with multiple legal systems and first show that legal pluralism leads to underinvestment by creating enforcement uncertainty. Second, there is an option value of additional legal systems, explaining why non-Muslim Ottomans sought to acquire access to European law. Third, in a competitive market where a subpopulation has access to additional legal systems, agents who have access to fewer jurisdictions exit the market. Thus, forum shopping explains protégés’ dominance in trade. Finally, the paper explains why the introduction of the French commercial code in 1850 failed to reverse these outcomes.

There is further interesting work at the link.

Assorted links

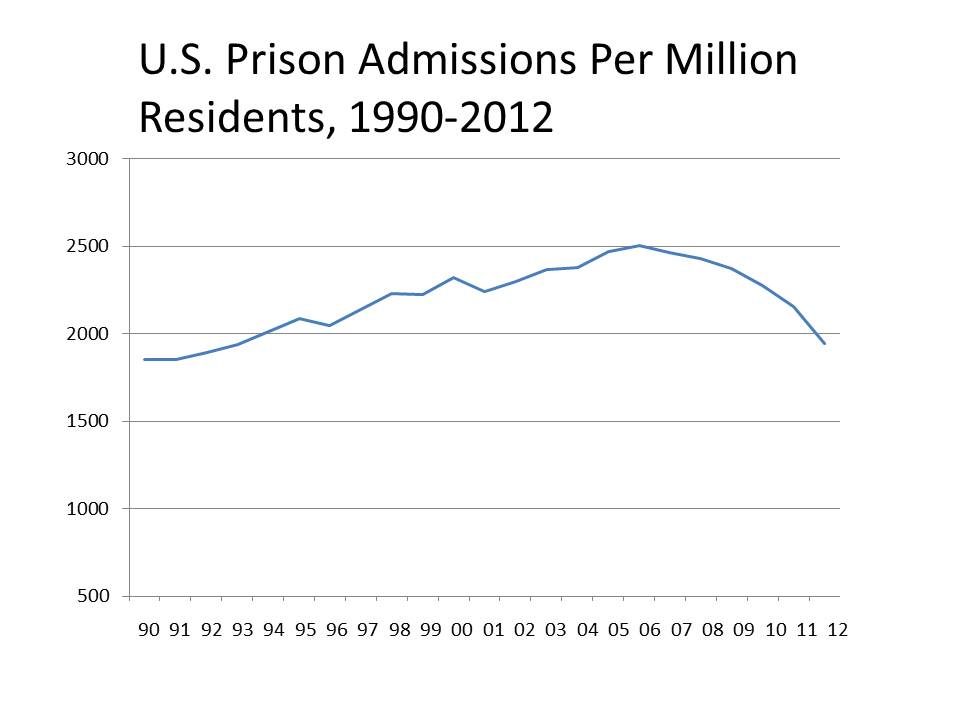

Prison Admission Rates are Falling

In an earlier post, I pointed out that after increasing for more than thirty years, prison populations have been begun to decline. Keith Humphreys further notes that the trend is even more dramatic when we look at the flow of people into prisons (rather than the stock).

In absolute numbers, the number of admissions in 2012 (609,800) was the lowest since 1999.

Drug-related imprisonments are especially down. In 1991, for example, 23% of the prisoner’s sentenced for more than one year were sentenced for drug related reasons (including 8.2% for drug possession). In 2011 only 16.6% of imprisonments for more than one year were for drug-related reasons (including 4.1% for drug possession.) This trend is likely to continue with further drug legalization.

Do Americans prefer hand-held foods?

Are there any dishes or foods that you would classify as typically, or even exclusively, “American?”

A number of iconic foods—hot dogs and hamburgers, snack food—are hand-held. They’re novelties associated with entertainment. These are the kinds of food you eat at the ballpark, buy at a fair and eventually eat in your home. I think that there is a pattern there of iconic foods being quick and hand-held that speaks to the pace of American life, and also speaks to freedom. You’re free from the injunctions of Victorian manners and having to eat with a fork and knife and hold them properly, sit at the table and sit up straight and have your napkin properly placed. These foods shirk all that. There’s a sense of independence and a celebration of childhood in some of those foods, and we value that informality, the freedom and the fun that is associated with them.

The resource costs of a gold standard

This is one of those topics which bugs me.

I’m not happy with counting the stock of “monetary gold” as the “resource costs of a gold standard,” as did Milton Friedman. We also hold stocks of oil, copper, and other commodities — how about books in libraries? — and no one considers inventories of those commodities as costs per se. For one thing, holding monetary gold in vaults still involves an option to convert into commodity uses and it may in essence serve as a useful commodity inventory for gold. Another way to put the point is that a properly capitalized bank can simply hold its gold in dental offices — or in wedding rings — if need be. How about if they hold their assets in the form of securities (T-Bills?) which can be, if needed, traded for gold mining stocks?

Is there a systematic market failure when it comes to locating inventories too close to major shipping centers? I don’t see why. But that’s arguably the same question as the one about the resource costs of a gold standard.

Or consider the Hotelling resource pricing rule, namely that a resource price should rise at the nominal rate of interest, with various adjustments for costs and changing costs and risk tossed in. Let’s say there is a gold standard and gold is also the medium of account. The price of gold rising at the nominal rate of interest thus means the general price level is falling at the nominal rate of interest. During the times of the classical gold standard, expected price inflation was roughly zero, but nominal interest rates were higher than zero. Either prices weren’t falling fast enough or nominal interest rates were too high or some mix of both. Say prices weren’t falling enough. Well, that is violating the Hotelling rule but in fact gold production is then falling short of an optimum, not exceeding it. Alternatively, you could toss in a liquidity rate of return on holding gold inventories and maybe then things would be just right.

A way to put this point more generally is that pricing some contracts in terms of a commodity does not itself create violations of the Hotelling rule. You might think that the liquidity premium on gold has to create an inefficiency, perhaps because social and private returns to liquidity differ. But do they, in the case of base money? Or isn’t the social return to liquidity arguably higher, if you see bankruptcy costs and benefits from thick capitalization using the liquid asset? In any case, the marginal liquidity return on money gold has to equal the marginal liquidity return on “commodity gold inventories” and then I am back to not being so sure there is a significant externality wedge.

It is unlikely that a final “all things considered” view will have the quantity of gold mined and held be just right. Yet as a first cut answer, postulating zero real resource costs for a gold standard is more reasonable than it might at first appear.

By the way, for macroeconomic reasons I’ve never favored a gold standard, but the resource cost argument has long seemed to me weak. All things considered, we might not end up digging up enough gold (liquidity) and that is the real worry we should hold.

The distributional incidence of QE and lower interest rates

A new McKinsey study has crossed my desk, “QE and ultra-low interest rates: Distributional effects and risks.” It offers a few estimates:

1. As a result of QE, governments in the US, UK, and Eurozone have benefited by about $1.6 trillion in lower debt service costs and profits remitted from central banks.

2. Households in those same countries have lost about $630 billion in reduced interest income.

3. Non-financial corporations have gained about $710 billion through lower debt service costs.

I would urge extreme caution in interpreting these or indeed any such results, as the nature of the no-QE-weaker-AD alternative scenario is hard to spell out and in any case would impose losses of its own. “Never reason from a pecuniary externality change” a wag once told me. Still, you can use those numbers as one example of a very rough “apply ceteris paribus assumptions to a macro problem” estimate.

One interesting takeaway from this report is that European life insurance companies may be in persistent financial trouble. Many life insurance policies are written for 40 or 50 years but the companies cannot find assets to match those durations. As the bonds they hold mature, they cannot easily reinvest in safe assets with yields comparable to what they are guaranteeing their policyholders. For instance some German life insurers are guaranteeing a return of 1.75 percent, but German ten year Bunds were yielding only about 1.54 percent (the report is from November). The insurance companies will either steadily lose money or be forced to seek out riskier investments, which is also to some extent prohibited by law and regulation. Here is one relevant Moody’s report, which explains why German life insurance companies are especially vulnerable. There are related readings here.

*F.A. Hayek and the Modern Economy*

That is a new volume edited by Sandra J. Peart and David M. Levy.

More than just the usual blah blah blah about Hayek, this book is full of original material. The book’s home page, with table of contents, is here.

And here is our recent MRUniversity class on Friedrich A. Hayek, and his Individualism and Economic Order.