Assorted links

A Few Favorite Books from 2013

Tom Jackson asked me for a couple of best books for his year end column. I don’t read as many books as Tyler so consider these some favorite social science books that I read in 2013.

In The Undercover Economist Strikes Back, Tim Harford brings his genius for storytelling and the explanation of complex ideas to macroeconomics. Most of the popular economics books, like The Armchair Economist, Freakonomics, Predictably Irrational and Harford’s earlier book The Undercover Economist, focus on microeconomics; markets, incentives, consumer and firm choices and so forth. Strikes Back is that much rarer beast, a popular guide to understanding inflation, unemployment, growth and economic crises and it succeeds brilliantly. Mixing in wonderful stories of economists with exciting lives (yes, there have been a few!) with very clear explanations of theories and policies makes Strike Back both entertaining and enlightening.

In The Undercover Economist Strikes Back, Tim Harford brings his genius for storytelling and the explanation of complex ideas to macroeconomics. Most of the popular economics books, like The Armchair Economist, Freakonomics, Predictably Irrational and Harford’s earlier book The Undercover Economist, focus on microeconomics; markets, incentives, consumer and firm choices and so forth. Strikes Back is that much rarer beast, a popular guide to understanding inflation, unemployment, growth and economic crises and it succeeds brilliantly. Mixing in wonderful stories of economists with exciting lives (yes, there have been a few!) with very clear explanations of theories and policies makes Strike Back both entertaining and enlightening.

Stuart Banner’s American Property is a book about property law, which sounds like an awfully dull topic. In the hands of Banner, however, it is a  fascinating history of what we can own, how we can own it and why we can own it. Answers to these questions have changed as judges and lawmakers have grappled with new technologies and ways of life. Who owns fame? Was there a right to own one’s own image? Benjamin Franklin, whose face was used to hawk many products, would have scoffed at the idea but after the invention of photography and the onset of what would later be called the paparazzi thoughts began to change. In the early 1990s, Vanna White was awarded $403,000 because a robot pictured in a Samsung advertisement turning letters was reminiscent of her image on the Wheel of Fortune. American Property is a great read by a deep scholar who writes with flair and without jargon.

fascinating history of what we can own, how we can own it and why we can own it. Answers to these questions have changed as judges and lawmakers have grappled with new technologies and ways of life. Who owns fame? Was there a right to own one’s own image? Benjamin Franklin, whose face was used to hawk many products, would have scoffed at the idea but after the invention of photography and the onset of what would later be called the paparazzi thoughts began to change. In the early 1990s, Vanna White was awarded $403,000 because a robot pictured in a Samsung advertisement turning letters was reminiscent of her image on the Wheel of Fortune. American Property is a great read by a deep scholar who writes with flair and without jargon.

On June 3, 1980, shortly after the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, the U.S. president’s national security adviser was woken at 2:30 am and told that Soviet submarines had launched 220 missiles at the United States. Shortly thereafter he was called again and told that 2,200 land missiles had also been  launched. Bomber crews ran to their planes and started their engines, missile crews opened their safes, the Pacific airborne command post took off to coordinate a counter-attack. Only when radar failed to reveal an imminent attack was it realized that this was a false alarm. Astoundingly, the message NORAD used to test their systems was a warning of a missile attack with only the numbers of missiles set to zero. A faulty computer chip had inserted 2’s instead of zeroes. We were nearly brought to Armageddon by a glitch. If that were the only revelation in Eric Schlosser’s frightening Command and Control it would be of vital importance but in fact that story of near disaster occupies just one page of this 632 page book. The truth is that there have been hundreds of near disasters and nuclear war glitches. Indeed, there have been so many covered-up accidents that it’s clear that the US government has come much closer to detonating a nuclear weapon and killing US civilians than the Russians ever did. Thankfully, we have reduced our stockpile of nuclear weapons in recent years but, as in so many other areas, we are also more subject to computers and their vulnerabilities as we make decisions at a faster, sometimes superhuman, pace. Command and control, Schlosser warns us, is an illusion. We are one black swan from a great disaster and if this is true about the US handling of nuclear weapons how much more fearful should we be of the nuclear weapons held by North Korea, Pakistan or India?

launched. Bomber crews ran to their planes and started their engines, missile crews opened their safes, the Pacific airborne command post took off to coordinate a counter-attack. Only when radar failed to reveal an imminent attack was it realized that this was a false alarm. Astoundingly, the message NORAD used to test their systems was a warning of a missile attack with only the numbers of missiles set to zero. A faulty computer chip had inserted 2’s instead of zeroes. We were nearly brought to Armageddon by a glitch. If that were the only revelation in Eric Schlosser’s frightening Command and Control it would be of vital importance but in fact that story of near disaster occupies just one page of this 632 page book. The truth is that there have been hundreds of near disasters and nuclear war glitches. Indeed, there have been so many covered-up accidents that it’s clear that the US government has come much closer to detonating a nuclear weapon and killing US civilians than the Russians ever did. Thankfully, we have reduced our stockpile of nuclear weapons in recent years but, as in so many other areas, we are also more subject to computers and their vulnerabilities as we make decisions at a faster, sometimes superhuman, pace. Command and control, Schlosser warns us, is an illusion. We are one black swan from a great disaster and if this is true about the US handling of nuclear weapons how much more fearful should we be of the nuclear weapons held by North Korea, Pakistan or India?

Is American politics ruled by gridlock?

My latest New York Times column is here, and here is one excerpt:

Consider the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. Coordinated actions by the Federal Reserve, the Treasury and Congress geared up rapidly, were decisive by global standards and received a fair amount of bipartisan support. In contrast, the euro zone is still discussing how to manage its bailouts or whether to start a program of quantitative easing, which the Federal Reserve will begin to wind down in January. And Japan, after letting problems with bad banks fester for decades, is only now using monetary policy to fight deflationary pressures.

After that initial decisiveness in the financial crisis, America did indeed slow down in policy innovation. Bailouts and our activist central bank have become extremely contentious factors in the nation’s politics, and there has been bitter fighting over how to set into motion the Dodd-Frank financial reform law.

Lunging and lurching forward with big changes, then enduring periods of backlash, consolidation and frustration, is often a better description of our political system than is “gridlock,” which is too unidimensional a concept to capture the reality.

At other times, because political flexibility is a fundamental part of the American system, it doesn’t feel as though we are defeating gridlock as much as bypassing it. Fracking — hydraulic fracturing — is reshaping the American energy sector, in part because of previous federal support for research and development, and in part because of regulatory tolerance: Many of the relevant changes took place through agencies like the Energy Department. In contrast, much of Europe is refusing to proceed with fracking at all. The American breakthrough has generated economic headlines, but rarely is it cited as an example of political success.

Do read the whole column. Two other examples are the building of the surveillance state and the shift toward ever-tougher forms of intellectual property protection, and the spread of that philosophy to other nations through the form of treaties. Sometimes we could use more gridlock, although I recognize that many people prefer to rail against it.

If you would like to read a defense of the gridlock view, here is Ornstein and Mann, noting that they confuse polarization with gridlock and don’t consider most of the examples and comparisons I raise. Their argument is closer to “we shouldn’t feel very good about how things have been running,” which I have no problem accepting. Here is Summers, responding to their critique., though he is more optimistic about the consequences of periodic non-gridlock than I am. Here is the original Summers Op-Ed. Many other contributions to the political science literature either predate the recent wave of rather considerable policy reform, focus on Congress, or focus on whether polarization is preventing us from addressing income inequality. I don’t intend those points as criticisms, simply a note that many of those pieces and books do not bear so directly on my thesis.

What I’ve been reading

1. M. John Harrison, Light. I thought I was sick of cyberpunk but this held my attention from the first page through the end. It falls in the category of “don’t worry if you don’t get everything that is going on, enjoy anyway.”

2. John Williams, Stoner. This is not quite the great lost American novel, as some critics are making it out to be. Nonetheless it is good, brisk, absorbing read about the horrible life of a stultified academic. First published in 1965.

3. Gary J. Bass, The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. The story of the India-Pakistan-Bangladesh-USA relations in the earlier 1970s and the conflict of that time, a very good book.

4. Lane Kenworthy, Social Democratic America, I will quote my blurb: “If you wish to read the case for a big increase in social welfare spending, this is the very best place to go.” Here is a related piece from the book.

5. Pete Earley, Comrade J: The Untold Secrets of Russia’s Master Spy in America After the End of the Cold War. A fun look at the Russian spy world behind “The Americans” (TV show), also with a fascinating discussion of the KGB in Ottawa spying on the Canadians.

6. John Limbert, Negotiating with Iran: Wrestling the Ghosts of History. Four detailed case studies of past failures and successes negotiating with Iran, from a scholar who knows his topic very well and can write clearly.

Assorted links

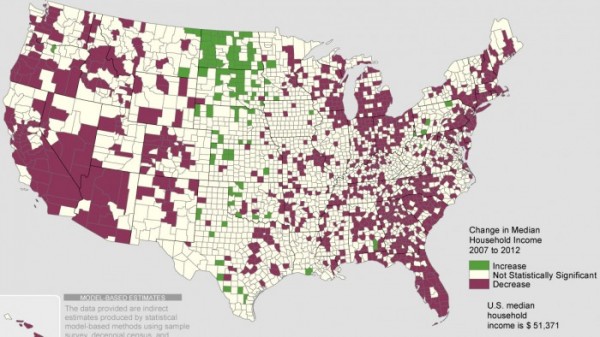

Where in the United States is median income growing?

That is from 2007 to 2012, the link is here.

Philip Tetlock’s Good Judgment Project

Philip emails me:

Your recent book was very persuasive–and I see an interesting connection between your thesis and the “super-forecasters” we have been trying to select and then cultivate in the IARPA geopolitical forecasting tournament.

One niche we humans can carve out for ourselves is, under certain fleeting conditions, out-smarting algorithms (one of the extreme challenges we have been giving our supers is out-predicting various wisdom-of-crowd indicators).You have brought us many forecasters over the years (including some “supers”) so I thought your readers might find the attached article on the research program in The Economist of interest.Our recruitment address is: www.goodjudgmentproject.com

The website writes:

The Good Judgment Project is a four-year research study organized as part of a government-sponsored forecasting tournament. Thousands of people around the world predict global events. Their collective forecasts are surprisingly accurate.

You can sign up and do it. Here is a related article from The Economist. Here is a good Monkey Cage summary of what they are doing.

Sumner on Krugman on the UK

Krugman also ignores the fact that his own graph shows fiscal policy in Britain getting more contractionary in 2013, and yet growth picked up sharply!

Read the whole thing. I also would note that the demand-side secular stagnation meme also seems to be gone or at least shelved in the cupboard, as today Krugman wrote: “Economies do tend to grow unless they keep being hit by adverse shocks.” The reallocation of labor from previous cuts in government spending is now seen unambiguously a good thing, whereas the previous argument was that in a liquidity trap such positive supply shocks could very well push economies into an even worse position. Most of all, British price inflation has continued at a robust rate and that is because of British monetary policy, again no sign of very low short rates being a “liquidity trap” in this regard. The UK labor market experience also seems to support Bryan Caplan’s repeated claims that real wage cuts really can put people back to work.

And here is a remark on timing:

I find it astonishing that Krugman and Wren-Lewis, having done post after post in 2012 describing how the UK does have real fiscal austerity in 2012, are suddenly happy to now argue that a relaxation of fiscal austerity in 2012 is the “reason” for GDP recovery in… erm, 2013.

Don’t let the emotionally laden talk of “Three Stooges” or “deeply stupid,” or continuing problems in the UK economy, distract your attention from the fact that this one really has not gone in the directions which the Old Keynesians had been predicting.

Assorted links

The Israel boycott is endorsed by the American Studies Association and Corey Robin

By a 2-1 margin, “An association of American professors with almost 5,000 members has voted to endorse an academic boycott of Israeli colleges and universities…” My earlier criticism of the boycott was here. A good Michael Kazin critique is here. Corey Robin defends the proposed boycott here. Robin’s argument is that change has to start somewhere, and we cannot boycott everything, so we might as well start with some boycotts that could work, even if that means singling out some targets unfairly.

I would start by applying a different standard. I would focus on the demands of the boycotters, and ask what is the chance that meeting those demands would work out well. The demands of the boycotters, in this case, include having Israel grant the “right of return” to Palestinians to the current state of Israel.

Now I understand the justice-based case for such a right, but what about the practicalities of such a change? The most striking feature of Robin’s boycott defense is that he doesn’t bother to argue this point.

In my untutored view, the chances that granting such rights would lead to outright civil war is at least p = 0.1, possibly much more, and the chances that such a change leads to a better outcome, in the Benthamite sense, are below p = 0.5. I readily grant these estimates may be wrong, but I don’t think they are absurdly wrong or implausible and in fact they represent a deliberate attempt on my part to eschew extreme predictions. An educated person or even a specialist might arrive at similar estimates or even more pessimistic ones. I would be curious to read Robin’s assessment.

By the way, you might think that the potential for bad outcomes is “the fault of the Israelis,” but that bears on the justice question, not on the Benthamite question. Don’t use “emotional allocation of the blame” to distract your attention from the positive questions at hand.

Why don’t we look at the world of science, where academic collaboration is actually um…useful?:

In science, however, the boycott movement has so far made comparatively few inroads.

“For us, it’s meaningless,” said Yair Rotstein, the executive director of the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), which was established in 1972 with an endowment funded by both countries. The boycott, he said, is something blown up in the media: for all practical purposes, “there really is no boycott.” Rotstein said that of about 7,000 requests to prospective external reviewers it sends each year, the foundation gets just one response on average from a scientist declining for political reasons.

Meanwhile, the BSF grants about $16 million in awards each year to American and Israeli scientists working on joint projects, having funded over the years, according to Rotstein, 42 Nobel Laureates. And since 2012, the BSF has partnered with the National Science Foundation to support collaborative research in biology, chemistry, computational neuroscience and computer science (The BSF gets an additional $3 million a year from the Israeli government to support these joint BSF-NSF projects.)

I still say this is not a boycott worth supporting. If we are going to do boycotts, and if we need to do boycotts, let’s do boycotts whose terms have a clearly positive Benthamite value with a minimum of extreme downside risk. There are plenty of those, and remember, we’ve been told that we need to be selective.

We’re back again to this whole thing being a lot of posturing. Note that the Palestinian government does not itself support boycotts of Israel. How about a small amount of solidarity with them?

Henrik Jordahl on Swedish education and its privatization

Not long ago I linked to an article suggesting there were some burgeoning problems with the Swedish educational privatization model. Henrik wrote me this email:

Dan, Tyler and others!

As the article claims there are really serious problems in Swedish schools – and it does not help that the minister of education from the liberal party does not seem to understand or be willing to admit what is going on.

Importantly, there is no evidence of the private (so called independent) schools or of the introduction of school choice contributing to worse performance. The two most relevant studies establishing this are:

1. Böhlmark, Anders & Lindahl, Mikael, 2013. “Independent Schools and Long-Run Educational Outcomes Evidence from Sweden´s Large Scale Voucher Reform,” Working Paper Series 6/2013, Swedish Institute for Social Research.

http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:675521/FULLTEXT01.pdf Finds that an increase in the share of independent-school students improves average performance at the end of compulsory school as well as long-run educational outcomes. Also finds that international test results (TIMSS) deteriorated less in Swedish regions with a higher proportion of independent school students.2. Wondratschek, Verena, Karin Edmark and Markus Frölich (2013). “The Short- and Long-term Effects of School Choice on Student Outcomes – Evidence from a School Choice Reform in Sweden”, IFN Working Paper No. 981. Forthcoming in Annals of Economics and Statistics. http://www.ifn.se/eng/publications/wp/2013/981 . Finds that increased school choice had very small, but positive, effects on marks at the end of compulsory schooling, but virtually zero effects on longer term outcomes.

Hope this is useful and not too late.

Friedrich A. Hayek class on MRUniversity

MRUniversity.com has a new class on Hayek’s Individualism and Economic Order, free on-line pdf version of the book is here. The class is based around my reread of the book — often considered the single best introduction to Hayek — and what I learned from each chapter., whether positively or negatively.

The MRUniversity videos are now available on the homepage of MRU at the end of the Great Economists section. There is also a landing page for all of the Hayek videos at once.

Overall the book held up very well upon my reread. The most interesting chapters — at least given my initial margins — were Hayek’s liberaltarian take on economic policy and Hayek on the likely evolution of European federalism. Hayek makes the very interesting argument that EU-like institutions will be classical liberal by default, as non-intervention tends to be the focal default point when conflicting nations cannot agree on very much. He thus thinks that supranational institutions, while often motivated by peace at first, over time become an instrument of economic freedom.

We invite you to check out the class, and of course there is more to come.

Kebko on North Carolina’s unemployment insurance experiment

#5: I think Evan is being a bit too broad with his interpretation of the labor market in North Carolina. There have been two distinct phases of labor force adjustments:

1) Between the passage of the law and its implementation, there was a small decrease in unemployment. But, mostly, on net, there was a decrease in employment and a corresponding decrease in labor force participation. The movement was from employment to not-in-labor-force. I don’t know if there is a straightforward way to interpret this, but I don’t believe Evan is addressing it cleanly in the article.

2) After the implementation of the law, labor force participation stabilized. Since that time, there has been a decrease in unemployment and an increase in the Employment to Population ratio. People are moving from unemployment to employment.

The first phase could have a number of interpretations. The second phase is clearly what opponents of Emergency Unemployment Insurance would have predicted. At this point, I think we still need to give it a few months to see if the rebound in the employment to population ratio continues. If it does, then this article by Evan will have been unfortunate.

Here is my post on the issue, with some graphs: http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2013/12/a-natural-experiment-on-emergency.html

Assorted links

1. Six case studies of writers who changed their minds. On what basis were they picked to contribute? And when you like the writer but not the books.

2. Markets in everything: I want to be Brahms’s German Requiem.

5. The North Carolina experience with cutting unemployment benefits.

6. Leading economists endorse Christmas presents, sort of. And Times Higher Ed best books list, deep and broad.

Shiller on Trills

In this short piece, Robert Shiller explains one of the basic ideas of his work on macro markets:

The governments of the world should issue shares in their GDPs, securities that pay to investors as dividends a specified fraction of GDP, in perpetuity (or until the government buys them back on the open market). Governments need to end their historic reliance on debt financing: governments issuing shares in GDP is analogous to corporations issuing equity. My Canadian colleague Mark Kamstra and I propose issuing trillionth shares in GDP, and so to call these “Trills.” Last year, a U.S. Trill would have paid $15.09 in dividends, a Canadian Trill C$1.72. The dividends will change every year as GDP is announced, and predicting these changes will certainly interest investors, just as in the stock market. Governments can auction off Trills when current government debt comes due and needs to be refinanced, as part of a debt reduction program.

In this piece, Shiller focuses on the benefits of Trills as opposed to debt:

Substituting Trills for conventional debt helps deleverage the government, something whose importance has become very clear with the debt crisis in Europe. The payments required of the government by the Trills is connected to the country’s ability to pay, measured by their GDP.

Trills could also be the foundation for many types of insurance products, for example, products that would pay off when GDP was down helping to alleviate business cycle issues. A market in Trills could also be used to make predictions and to judge policies (see Gurkaynak and Wolfers for an early test). Which policies will most increased the value of future trills? Similarly, by looking at how the market for trills changes as the Iowa Political Markets change we could identify which politicians are best for GDP (not just the equity and bond markets).

I featured Shiller’s work on macro markets in my book Entrepreneurial Economics: Bright Ideas from the Dismal Science. I think of this body of work as his most visionary and deserving of the Nobel.