Assorted links

1. Photos of depreciated capital.

2. Dress turns transparent when you get aroused (the link is not totally safe for work, though within that category fairly tame).

3. The culture that is Italy (video).

4. Discussion of Super Bowl lighting contingencies.

5. One anthropologist looks at Diamond and the early history of warfare.

Good sentences about fashion and copying

The mass copying of a style is what creates a trend, and trends sell clothes today. This is why many in the industry furiously protect their right to ripping each other off. Two law professors, Kal Raustiala and Chris Sprigman, have argued against the design piracy act on the grounds that the American apparel industry “may actually benefit” from copying, as it speeds up the creation and exhaustion of trends.

Note the clever assignment of the externality. Rapid copying is needed for customers to develop the expectation that trends come and go rapidly, and thus to get customers to visit the store and buy today. Yet no single business will invest enough on its own in creating these broader expectations, because the industry as a whole reaps the benefit. The “copying game” induces the sellers to, in essence, act collusively to help establish these “hurry up and buy now” expectations.

The quotation is from Elizabeth L. Cline’s Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, which I quite enjoyed reading, despite some glaring weaknesses when it comes to FDI, wages, and foreign development. I now understand the affordable yet fashionable clothing stores in Tysons Corner Mall, and how they have changed over the last fifteen years, and I can thank this book for that.

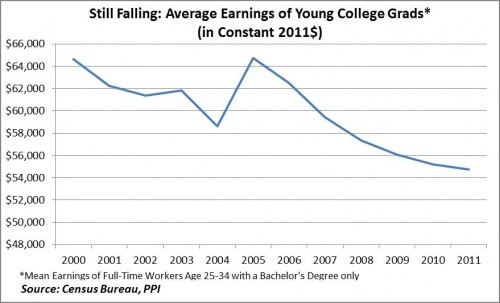

Average earnings of young college graduates are still falling

Alas, take a look:

Diana G. Carew, who works with Michael Mandel, reports:

The latest Census figures show real earnings for young college grads fell again in 2011. This makes the sixth straight year of declining real earnings for young college grads, defined as full-time workers aged 25-34 with a bachelor’s only. All told, real average earnings for young grads have fallen by over 15% since 2000, or by about $10,000 in constant 2011 dollars.

That picture is the single biggest reason why higher education in this country is in economic trouble as a sector. And yes, I do understand that the “education premium” is robust, but that means wages for non-college workers have been hurting as well. At some margin, when it comes to determining how much you will pay for college, the absolute return matters too. The full article is here.

Not so Simply Orange juice

Simply Orange juice is actually not all that simple. The taste of the the Coca-Cola-owned brand is governed by a complex algorithm that allows for the 600+ juice flavors to be tweaked throughout the year to ensure consistency.

From Jason Kottke, here is more. And from The Atlantic, here is further explanation:

The algorithm is designed to accept any contingency that might affect manufacturing, from weather patterns to shifts in the global economy, and make adjustments to the manufacturing process accordingly. Built into the model is a breakdown of the 600-plus flavors that are in orange juice that are tweaked throughout the year to keep flavor consistent and in line with consumer tastes. Coke even sucks the oxygen out of the juice when they send it to be mixed so that they can keep it around for a year or more to balance out other batches. Doug Bippert, Coke’s vice president of business acceleration, calls it “a flight simulator for [Coke’s] juice business.” (Funnily enough Delta uses the same algorithm to balance its books.) “If we have a hurricane or a freeze,” Bippert added, “we can quickly replan the business in 5 or 10 minutes just because we’ve mathematically modeled it.”

Assorted links

1. Markets in everything, iPad edition.

2. Krugman further explains his views on Japan.

3. Derek Thompson’s skepticism about robots. I say the correct view is not about “robots” putting people “out of work,” but rather how software and machine intelligence are restructuring relative wages, which in turn has subsequent implications for labor force participation rates.

4. How much healthier are the baby boomers?

Will health insurance premia rise for young males?

I suspect the analysis cited in this article is an exaggeration, but it is even more than I thought the exaggeration would be:

The survey, fielded by the conservative American Action Forum and made available to POLITICO, found that if the law’s insurance rules were in force, the premium for a relatively bare-bones policy for a 27-year-old male nonsmoker on the individual market would be nearly 190 percent higher.

…Insurers have been reluctant to share their premium projections for a variety of reasons, but Holtz-Eakin, through a lawyer intermediary, was able to get aggregated, anonymous data under a nondisclosure agreement. On average, premiums for individual policies for young and healthy people and small businesses that employ them would jump 169 percent, the survey found.

Note that subsidies would cushion such price shocks for lower-income individuals and that the premia for older and less healthy people would fall, by twenty-two percent according to a comparable estimate (do not forget that a smaller percentage figure is being applied to a larger absolute number). From a distance, it is difficult to judge how realistic these projections are.

Still, I would think that the chance of younger individuals refusing to adhere to the mandate is higher than Massachusetts-linked projections have been indicating.

I would say that in recent times there has been a string of bad news about ACA and few new reported items of good news.

Addendum, from the comments, from Carl the Econ Guy:

The whole survey is here:

http://americanactionforum.org/sites/default/files/AAF_Premiums_and_ACA_Survey.pdf

Look at Table 1– where it says that the average premium for young healthy males will go from $2,000 to a little over $5,000. Yikes.

A simple macro model of collateral

Regulators are pushing for non-centrally cleared trades to be backed by high levels of collateral, such as cash or government bonds. This is where the $10tn figure comes in. It is the amount of extra collateral that could be required according to estimates by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

Here is the full FT article. It stresses that figure of ten trillion may be too high an estimate, but a separate lower estimate still runs at $2 to $4 trillion.

Let’s play out the scenario. In some future world, what if most savings is done by corporations and also by traders at the clearinghouse, in the form of collateral. Collateral, however, is not “smoothed” across assets but rather is an either/or decision. They won’t take your sheepdog as collateral, nor will they take shares in small tech companies. Most of the saving is done in the form of approved safe assets and the rest of the economy is somewhat starved for investment.

I call it the return of financial repression. Let’s see how far it is allowed to go.

The Cyprus bailout

No one wants to bail out Cyprus because it is “Greece with dodgy banks,” one third Russian depositors, a tax haven, corrupt, and the banking system is measured at eight times the size of the real economy. Even a pro-bailout politician may not wish to soil the name of bailouts by handling this case. The Germans are balking.

But if depositors take losses in Cyprus, what kind of precedent does this set?

One risky scenario is that it sets off a run on some of the weaker eurozone banks.

A better case scenario is that the market distinguishes Cyprus from the other cases (all of them? some of them?) in the eurozone and European Union. But that too involves a trick. Let’s say the market can distinguish Cyprus from Spain. Can the market also distinguish Greece from Spain? Is it good to break the expectation of “we’re all in this together,” even when doing so is justified?

A systemically costless fail of credit obligations in Cyprus is itself risky. It leads people to start wondering what else might be a systemically costless fail and testing that boundary. (“If we let Greece go, maybe they’ll know we are still committed to Spain…”) Which means a Cyprus fail might be systemically costly in the first place.

Developing…

Acemoglu and Robinson on the great stagnation

Two things are absent in this debate, however.

First, much evidence shows that what determines technological innovations isn’t some sort of “exogenous innovation capacity,” but incentives…

Schmookler illustrated these ideas vividly with the example of the horseshoe. He documented that there was a very high rate of innovation leading to improvements in the horseshoe throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries because the increased demand for transport meant increased demand for better and cheaper horseshoes. It didn’t look like there was any sort of limit to the improvements or any evidence of an “exogenous innovation capacity” in this ancient technology, which had been around since 2nd century BC. Then suddenly, innovations came to an end, but this had nothing to do with running out of low hanging fruit. Instead, as Schmookler put it (p. 93), it was because the incentives to innovate in this technology disappeared because “the steam traction engine and, later, internal combustion engine began to displace the horse… “

Their full post is here.

I have changed my mind on this issue quite a bit over the last four to five years. Yes incentives matter, but outside of extreme environments are changes in incentives explaining the changes in what we observe? I now think it is of critical importance where a sector or economy is on “the innovation curve.” It was easier to innovate in game theory in the 1980s than it is today, even though the salaries of top economists have risen significantly. The pharmaceuticals market is larger than ever before, and yet the pipeline is largely dry. We are simply at a point where further breakthroughs are hard (and it is not obvious that FDA innovation taxes are getting worse over this period of change.) Weren’t so many inventors of the 19th century largely “yahoos,” with no fancy degrees, relatively low pay, little or no peer review, not at the peak of the Flynn effect, and so on, and yet they were on a fruitful part of the innovation curve and performed wonders.

I think in terms of general purpose technologies and platform-like breakthroughs. Once you get them, innovation runs wild, otherwise it is tough sledding, with incentives still accounting for some of the variation within a particular place on the innovation curve.

Assorted links

New Teaching Tools

Gary King and Maya Sen discuss some of innovative ways that they use technology to teach Gary’s legendary class in statistics and social science at Harvard. Here is one bit

Instead of prohibiting smart phones in class, we require them …We then automatically deliver to their device a difficult conceptual question. We then give students a few minutes without discussion to reflect on the question and to indicate their answer on their device.

…Next, our system automatically puts students into groups of 2–5 [the system tells the students which other students to talk with and where to move in the classroom to find their group, AT]…We use an empirical approach to create the groups so that the conversation will be maximally productive. This is a system that is continually

updated, but for predictors we begin with data collected to characterize each student at the

start of the semester and add each student’s initial answer to the question just asked, their

answers to all previous CAPI questions and answers, their experience in the system, and

how productive previous CAPI discussions they participated in were. Finally, data from

thousands of other similar students in hundreds of other classrooms taking similar courses

can be used as well.We then ask the students to try to persuade the other members of their group of the

veracity of their answers. Since social connections motivate, we often get highly animated

discussions…Since teaching teaches the teacher, the students trying to persuade their

classmates improves their understanding of the subject matter.…We then deliver the same question to each student’s device again and have them answer

it. A minute or two later we project on the screen in front of the classroom a summary

of the answers before and after discussion, which gives them immediate feedback.…When it works best — which, like in survey research, is primarily a function of us

asking sufficiently clear questions — the proportion of correct student answers increases

from 20% to more than 80%.

Note that this particular technology recommendation is a bit of plumping for Gary’s company with Eric Mazur, Learning Catalytics. Nevertheless, I think these types of technologies pair very well with online education. It’s a mistake to think that online education is just delivery of lectures–online lecture delivery is merely a leading example of how information technology is revolutionizing education.

Good shop name

That is from the web site of Nancy Hanrahan, who teaches sociology and critical theory and music at George Mason. Just recently I was talking to a Polish man whom I met standing in front of The Village Vanguard, and who claims to own 20,000 jazz LPs, and he told me that Nancy is married to Kip Hanrahan, the esteemed yet still underrated jazz musician, start with Desire Develops an Edge.

“What I learned reading every last word of *India Today*”

The 6th floor blog of the NYT invited me to write a blog post on that topic, and so here it is. Excerpt:

4. The gap between the age of the average Indian and the age of the average Indian political leader is one of the largest in the world. No prime minister of the country has been born after 1947.

…9. The All India Council for Technical Education has the following ambitions: “Entropy in the Universe should rise indicating that the well-being of the Universe is improving. If I can contribute to the well-being of our society and make an addition to the entropy, I am happy. On a different note, we have now developed the National Vocational Education qualification framework. . . .”

Read the whole thing.

Mark Thoma’s spending cuts

Here is a Mark Thoma comment on my recent column, here is the introduction:

I’m all for more cuts to defense too, but it’s only fair to note that some cuts have been made there already.

Also, why are only spending cuts mentioned when the discussion is the budget? Please don’t tell me that if it’s not spending cuts, i.e. if it’s a tax increase, it doesn’t count for budget discussions (and Keynesian economics, which is part of his discussion, does not make this distinction). Thus, note also that the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) added another half trillion in deficit reduction. Together, the $1.5 trillion in appropriations cuts, plus the $.5 trillion in tax increases in the ATRA, plus the $300 billion in interest savings amount to around a bit over $2.3 trillion in deficit reduction…

Not once in Mark’s post does the word “baseline” appear. In fact I covered the defense “appropriations cuts” in my piece, noting that relative to baseline, even with the sequester (much less without) defense spending is roughly constant in real terms. Mark simply doesn’t recognize I made that point but instead portrays me as oblivious to the issue. (Additional comments from Angus here). I don’t see that as much evidence for our fiscal rectitude.

Or let’s look at the bigger picture of the back and forth. Take Mark’s sentence: “Also, why are only spending cuts mentioned when the discussion is the budget?”, after which he refers to tax increases. My very last column I called for tax increases, a bit now and more later. Mark covered that column. What was Mark’s reaction then? He complained that I didn’t also call for rectification of the content of government spending decisions and income shares, in both cases toward greater egalitarianism.

I see Mark as falling into a bad habit here, namely he encounters a specific argument which makes him uncomfortable and then looks around for reasons to reject or downgrade the source of that argument, rather than focusing on the argument itself.

Mark also accuses me of being ideological. That’s in the eye of the beholder. In this week’s column I called for cuts in farm subsidies (or abolition), Medicare, and defense, and switching out of any possible cuts in infrastructure or support for basic research. That’s pretty close to the consensus of economists. Elsewhere I’ve called (repeatedly) for significant increases in science funding and the fixing of LaGuardia airport, among other infrastructure projects. In the column I argue that there are both demand-side and supply-side reasons for drawing the distinctions I do between which parts of spending should be boosted and which should be cut. I argue that Keynesian economics is valid if applied correctly. Ryan Avent, not a member of the Tea Party, says he has “some sympathy” for my views on the sequester. I don’t doubt that I am to the libertarian side of Mark, but if he finds that all too ideological, and worthy of a calling out, I think he is skating at a margin where he will find it very difficult to learn from the people who disagree with him.

Assorted links

1. Why are there so many murders in Chicago?

2. Edward Luce in the FT on robots, on-line education, MRUniversity.com, and falling median income.

3. The economics of Netflix’s new $100 million show.

4. Print me a condo on the moon (speculative), and why name a brand after a retina?

5. People getting mad at Jared Diamond, and more here. Mood affiliation aside, the facts are on Diamond’s side.

6. We overregulate and underregulate too much at the same time.