How much might marginal tax rates be going up?

Gerald T. Prante and Austin John have a new paper and a report for us:

This paper compares state-by-state estimates of the top marginal effective tax rates (METRs) on wages, interest, dividends, capital gains, and business income for tax year 2012 to the rates scheduled for 2013 under scheduled law. Scheduled tax law for 2013 assumes the expiration of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts and the new PPACA taxes. Overall, the average top METR on wage income is scheduled to increase by approximately six percentage points (41.8 percent to 47.8 perent), while taxes on dividends would increase the greatest (19.0 percent to 47.9 percent). The top METRs on wages, dividends, interest, and partnership/sole proprietor income would exceed 50 percent in California, Hawaii, and New York City.

How many bankruptcies to come in higher education?

Bryan Caplan doubts that on-line education will lead to many bankruptcies in higher education. To provide a contrasting point of view, I see the landscape as follows:

1. The absolute wages of college graduates have been falling for over a decade, even though the relative premium over “no college degree” is robust. Still, absolute wages do determine the long-term viability of any revenue model. And note that a pretty big chunk of the relative college wage premium is captured through post-secondary education only.

2. The “debt bubble” behind a lot of recent higher education expansion won’t be repeated anytime soon.

3. A large number of institutions in the top one hundred will move to a hybrid on-line model for a third or so of their classes and they will do so gradually, without seriously disrupting norms of conformity or eliminating campus life. In fact this will become the new conformity and furthermore through time-shifting it may increase the quantity and joy of drunken parties and campus orgies. Eventually these on-line classes will be sold for credit to outside students. Some top schools will sell credits in this manner, even if the more exclusive Harvard and Princeton do not. Many lesser schools will lose a third or so of their current tuition revenue stream. Note that the prices for these on-line credits, even if hybrid, will likely be much lower, plus lesser schools lose revenue to the schools better at designing on-line content.

4. Some state governors will try to put out a supposedly semi-passable degree from their state schools for 10k a year, with some on-line components of course. That will put price and revenue pressure on many other schools.

So let’s say you are Trinity International University, in Deerfield, Illinois, 1,265 students, nominal tuition about 26k. I had never heard of that place before doing a quick search through U.S. News rankings. Still, it is rated in the second tier. Will it survive? Maybe their Evangelical orientation will push them through. Maybe it will sink to 500 students.

How about Lynn University, in Florida, also second tier, nominal tuition listed as 32k? 1,619 students, but how many by say 2032?

I don’t think bankruptcy, literally interpreted, is the likely legal outcome (for one thing, these schools probably don’t have enough debt for bankruptcy law to be relevant). Still, I think it is quite possible that one hundred or more schools in the U.S. News rankings will find their enrollments or at least their tuition revenue streams cut in half or more within twenty years. They will be shells of their former selves, though on-line education might not even be their major economic challenge. It will be one of three or four major whammies facing them. Higher education as a general practice of course still will thrive, as will community colleges.

One key question is whether on-line education will encourage consolidation or not. Under one vision, on-line offerings shore up the smaller schools, because you can go to them for the atmosphere while taking German III purely on-line. (Even then, they survive but the revenue stream takes a huge whack.) Under another vision, on-line — for most students — works best in hybrid form, mixed with various face-to-face forms, and the larger schools will have a much easier time getting this off the ground in a workable manner.

Two additional comments on Bryan’s post. First, he thinks that for on-line education “…the dollars of venture capital raised are laughable.” Yet keep in mind that the major players are or can be backed by the endowments of the top universities. In any case, why raise extra money before you are able to spend it? If these on-line efforts get any traction at all, the funding and lines of credit will be there.

Second, advocates of the relevance of the signaling model should be relatively optimistic about on-line education. Because it is hard to pay attention in the on-line schoolhouse, it provides an especially potent signal! And you always face the temptation to upgrade your signal by subbing in some Top School on-line credits for some of your Podunk University credits. (Sooner or later Podunk will have to accept such credits.) Social pressures for conformity will encourage rather than stop that trend. On the other hand, if you subscribe to a learning model for higher education, there are some very legitimate questions as to how well the on-line product can teach you what you need to know, at least for people with some fairly wide variety of learning styles.

Conformity pressures and signaling may militate against the “stay at home all day” forms of on-line education, but not against on-line education more generally, in fact quite the contrary. In my view Bryan is underestimating the economic problems to be faced by a wide range of colleges and universities, and putting up a not very plausible model of non-conformist on-line ed as the major threat.

Addendum: Matt Yglesias comments.

Books in my inbox

Amy J. Binder and Kate Wood, Becoming Right: How Campuses shape Young Conservatives.

Michael Huemer, The Problem of Political Authority: An Examination of the Right to Coerce and the Duty to Obey.

Assorted links

1. A perpetually disappointed Amazon reviewer (via Seth Roberts).

2. Part one of the Sidney Awards, by David Brooks.

3. What ranks high on the list of one’s life thrills?

4. California taxpayers do not endorse arts giving.

5. When will Saudi Arabia change?

6. Can we afford chimpanzee retirement, or will there be chimpanzee austerity?

Happy Holidays to MR Readers!

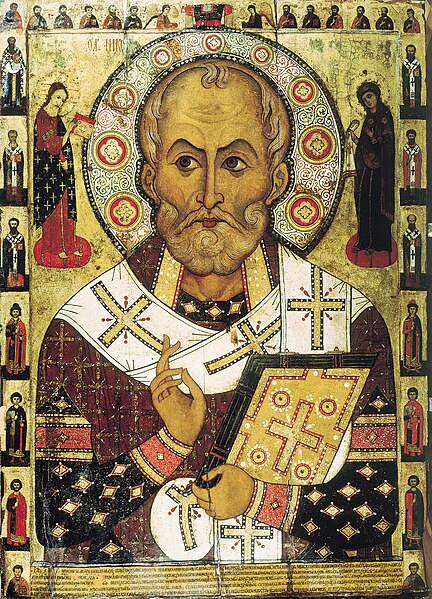

Merry Christmas!

Vending machine auction markets in everything

…ecoATM, a firm based in San Diego…has devised and deployed in several American cities a series of ATM-like devices that will automatically analyse your mobile phone, MP3 player or phone charger, and then make you an offer for it. These machines will give you cash in hand or, if you prefer, send the money as a donation to the charity of your choice. The hope is that this hassle-free approach will appeal to people who can’t be bothered to recycle their old phone when buying a new one.

After taking fingerprints and driving-licence details (to discourage crooks from using them to fence stolen goods), ecoATM’s kiosks employ a mixture of computer vision and electronic testing (they will automatically present users with the correct cable and connector) to perform a trick that even the most committed gadget fan might struggle with—telling apart each of the thousands of models of mobile phones, chargers and MP3 players that now exist. They can even make a reasonable guess about how well-used (or damaged) a device is, which can affect its resale value. Any mistakes the machine does make are logged and used to improve accuracy in future.

Once the device on offer has been identified, the kiosk then enters it into an electronic auction. Interested parties bid, and a price is struck in seconds. This auction is the key to ecoATM’s business model, because it means the firm is acting as a broker, rather than carrying a stock of second-hand equipment which it then has to sell. If the owner of the equipment accepts the offer, the kiosk swallows the device and spits out the money.

Really. The article is here.

Assorted links

Why would you write a bum check to God? (model this)

Maybe you are hoping that God will make the check a good one? From the Western Wall in Jerusalem:

Rabbi Shmuel Rabinovitch, who oversees Jerusalem’s Western Wall, said a worshipper found an envelope at the site Wednesday with 507 checks in the amount of about $1 million each. They were not addressed to anyone, and it’s doubtful they can be cashed.

Rabinovitch said most are Nigerian. Israeli police spokesman Micky Rosenfeld said some were from the United States, Europe and Asia.

The story is here and for the pointer I thank Mark Thorson.

The story of GiveDirectly

Paul Niehaus, Michael Faye, Rohit Wanchoo, and Jeremy Shapiro came up with a radically simple plan shaped by their own academic research. They would give poor families in rural Kenya $1,000 over the course of 10 months, and let them do whatever they wanted with the money. They hoped the recipients would spend it on nutrition, health care, and education. But, theoretically, they could use it to purchase alcohol or drugs. The families would decide on their own.

…Three years later, the four economists expanded their private effort into GiveDirectly, a charity that accepts online donations from the public, as well. Ninety-two cents of every dollar donated to GiveDirectly is transferred to poor households through M-PESA, a cell phone banking service with 11,000 agents working in Kenya. GiveDirectly chooses recipients by targeting homes made of mud or thatch, as opposed to more durable materials, such as cement or iron. The typical family participating in the program lives on just 65 nominal cents-per-person-per-day. Four in ten have had a child go at least a full day without food in the last month.

Initial reports from the field are positive. According to Niehaus, GiveDirectly recipients are spending their payments mostly on food and home improvements that can vastly improve quality of life, such as installing a weatherproof tin roof. Some families have invested in profit-bearing businesses, such as chicken-rearing, agriculture, or the vending of clothes, shoes, or charcoal.

More information on GiveDirectly’s impact will be available next year, when an NIH-funded evaluation of the organization’s work is complete. Yet already, GiveDirectly is receiving rave reviews.

Here is a good deal more. Here is one of my earlier posts on zero overhead giving. Here is Alex’s earlier post. Just last week I met up with one of the recipients of one of my 2007 donations and I am pleased to report he is doing extremely well as an actor and filmmaker.

Here is the site for GiveDirectly. Here is one very positive review of the site, from GiveWell.

A Parting Thought: Market v. Political Entrepreneurship

Thanks again to Alex and Tyler for having me as a guest blogger this week. It has been a pleasure sharing thoughts with you about ideas, fashion, and politics.

My last nugget for the week is about how market and political entrepreneurs learn differently from failure. Market entrepreneurs learn from the relentless forces of profit and loss. They even host conferences and websites where they speak openly about their failures. In part because political entrepreneurs lack the same signals of profit and loss, this type of learning does not happen to the same extent in political markets. My co-author Wayne has further analysis on our blog.

What is the potential for 3-D printing?

I think 3-D printing will happen, and indeed already is happening, but I don’t see that it will bring a utopian new future. From a recent New Scientist article (gated, related version here), here are two points:

…it’s difficult to print an object in more than one or two materials…

And:

…these combined hardware and materials issues mean that only a relatively small proportion of all people will end up printing out objects themselves. A more likely scenario is the growth of online services like Shapeways…or perhaps neighborhood print shops.

Maybe I’m blind, but I don’t yet see this as a technological game-changer. It seems more like a way of saving on transportation costs. To put it another way, what’s the huge gain of making everyone a manufacturing locavore? Perhaps there will be some new flurry of home-based innovation, based on tinkering from what these printers can drum up, but that seems to me quite speculative.

How to resolve the fiscal cliff

In my latest column, I suggest another strategy, one the current Republican Party seems quite far from:

To see how this could work, consider this script: Let’s say the Republicans decide to largely give in to what the President Obama is proposing. There is, however, a catch: the president has to agree to raise marginal tax rates on all income classes, not just on the rich. The tax increase would be one-quarter of a percentage point, or some other arbitrary small amount, with larger increases possible for higher incomes, as has been discussed. The deal also stipulates that both the president and Congress must publicly acknowledge that current plans for government spending can’t be financed unless taxes on most or all income groups climb further yet, and by some hefty amount.

Given the slow economy, it is undesirable to reverse all or even most of the Bush tax cuts. A small but publicly trumpeted clawback of some of the cuts would send the right message to voters, while minimizing the macroeconomic fallout. The nice thing about symbols — single shots across the bow — is that they often can suffice.

If people already rationally expect these tax increases, this signal would do neither good nor harm, but perhaps such an approach would nudge political expectations closer to reality without draining the economy.

And this:

In the minds of many moderate and independent voters, the Republicans are currently identified with dysfunctional politics. But this proposal would let them take a credible stand against obstructionism. If the president didn’t like such a deal, he would be the naysayer, and the resulting publicity would shine a bright spotlight on the tax-and-spend mismatch. Suddenly, it would be the Republicans emphasizing the classic American line that “we are all in this together.”

Read the whole thing.

Markets in everything

Private investors in Switzerland, Austria and Germany are lining up to buy gold bars the size of a credit card that can easily be broken into one gram pieces and used as payment in an emergency.

The story is here and for the pointer I thank the excellent Mark Thorson.

Ideas and Political Entrepreneurs: The Case of Airline Deregulation

Following up on my post from yesterday, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) regulated U.S. airline rates and routes from the 1930s through the 1970s. It also kept mountains of data. Aspiring Ph.D. candidates found worthy dissertation material from the agency’s files. The research lent support to an important idea—regulation was failing in this market—but no one listened to these young academic scribblers.

By the early 70s, an established academic produced a groundbreaking treatise arguing for sensible regulation. Alfred Kahn would soon make the jump from academic to regulator—of public utilities in the State of New York, not airlines.

By the mid-1970s, criticism of airline regulation had moved from academics to economists in think tanks (Brookings, AEI) and in government. At an economic conference on inflation convened by the Ford Administration, the delegates focused unexpectedly on a different idea: existing regulations were producing high prices. Yet as every economist in Washington knows, many reform ideas never become policy. Then came the political entrepreneurs.

First, Senator Ted Kennedy. An ambitious member of the Senate Judiciary Committee and chairman of the subcommittee on administrative procedure, Kennedy saw an opportunity to attack the over-regulated and under-competitive airline industry by critically examining the rules it played by.

Most judiciary subcommittee hearings were mind-numbingly boring, but airlines were sexy, and Kennedy turned the CAB hearings into high theatre, trotting out real but outrageous examples. A flight from Los Angeles to San Francisco (intrastate and thus not CAB-regulated) cost half as much as a flight from Washington to Boston (interstate and CAB-regulated). Even the dimmest reporter could connect the dots. The CAB looked bad. Kennedy looked good, as did the odds for reform.

Then the Carter Administration tapped Kahn to run the CAB. He allowed “experiments” in price flexibility (Super Saver fares). He approved new routes. Eventually, he questioned the agency’s purpose. The CAB had to go. This meant Kahn had to sell a very big idea to the madmen in authority, the decision-makers in Congress.

An accomplished economist who dabbled in theatre on the side, Kahn played his role perfectly. The former academic scribbler was funny, smart, patient and on point. He was a master communicator with press and politicians alike.

Kahn built on Kennedy, who built on the work of intellectuals in Washington’s think tanks and policy circles, who in turn built on good academic research. Importantly, he found allies across the political spectrum, from the American Conservative Union to Common Cause, from business interests to consumer groups. This odd mix prevented easy dismissal of reform as the pet project of the left, the right, or any special interest.

With passage of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, Congress closed the CAB and left behind an unprecedented example of radical reform. A better idea had made its way from academic scribblers, through the intellectuals and on to madmen in authority, who were compelled to act. Yet so much of the story hinges on the actions of Kennedy and Kahn—two very different individuals, two very effective political entrepreneurs.