Words of wisdom

Referring to the forthcoming ban on “plain-vanilla 100-watt incandescent bulbs” (California is already there), Virginia Postrel writes:

If they’re really interested in environmental quality, policy makers shouldn’t care how households get to that total. They should just raise the price of electricity, through taxes or higher rates, to discourage using it.

Instead, the law raises the price of light bulbs, but not the price of using them. In fact, its supporters loudly proclaim that the new bulbs will cost less to use. If true, the savings could encourage people to keep the lights on longer.

“It is too soon to tell” — the real story China fact of the day

The impact of the French Revolution? “Too early to say.”

Thus did Zhou Enlai – in responding to questions in the early 1970s about the popular revolt in France almost two centuries earlier – buttress China’s reputation as a far-thinking, patient civilisation.

The former premier’s answer has become a frequently deployed cliché, used as evidence of the sage Chinese ability to think long-term – in contrast to impatient westerners.

The trouble is that Zhou was not referring to the 1789 storming of the Bastille in a discussion with Richard Nixon during the late US president’s pioneering China visit. Zhou’s answer related to events only three years earlier – the 1968 students’ riots in Paris, according to Nixon’s interpreter at the time.

How so?

At a seminar in Washington to mark the publication of Henry Kissinger’s book, On China, Chas Freeman, a retired foreign service officer, sought to correct the long-standing error.

“I distinctly remember the exchange. There was a misunderstanding that was too delicious to invite correction,” said Mr Freeman.

He said Zhou had been confused when asked about the French Revolution and the Paris Commune. “But these were exactly the kinds of terms used by the students to describe what they were up to in 1968 and that is how Zhou understood them.”

But will this revelation diminish the use of this story? Dare I say it is too soon to tell? By the way:

The oft-quoted Chinese curse, “May you live in interesting times”, does not exist in China itself, scholars say.

Assorted links

1. Did I tell you the one about the man carrying a dead weasel?

2. The Industrious Revolution.

3. List of Catania businesses which have pledged not to pay tribute to the Mafia.

4. Should we abolish formal lecturing?

5. Via Chris F. Masse, 108 Chinese infrastructure projects that will change the world.

Assorted Links

1. Richard Florida adds interesting data on skills to the great male stagnation debate.

2. Freedom in the 50 States; New Hampshire is first. Appropriate.

3. Excellent pictures of the Bolivian salt flats.

4. Attorney-General Eric Holder wants a new season of The Wire. David Simon names his conditions.

5. The Corporatist Threat to the Arab Spring, good op-ed by Edmund Phelps. Recall, The Pharaoh and the Commanding Heights.

6. Soviet Dolphin Paratroopers.

7. Rinderpest is no more. Only the second time in history—smallpox was the first—that an infectious disease has been eradicated from the planet.

India’s Voluntary City

Fascinating piece in the NYTimes about a new city in India, a new city of 1.5 million people and more or less no city government.

Gurgaon was widely regarded as an economic wasteland. In 1979, the state of Haryana created Gurgaon by dividing a longstanding political district on the outskirts of New Delhi. One half would revolve around the city of Faridabad, which had an active municipal government, direct rail access to the capital, fertile farmland and a strong industrial base. The other half, Gurgaon, had rocky soil, no local government, no railway link and almost no industrial base.

As an economic competition, it seemed an unfair fight. And it has been: Gurgaon has won, easily. Faridabad has struggled to catch India’s modernization wave, while Gurgaon’s disadvantages turned out to be advantages, none more important, initially, than the absence of a districtwide government, which meant less red tape capable of choking development.

Gurgaon has no publicly provided “functioning citywide sewer or drainage system; reliable electricity or water; public sidewalks, adequate parking, decent roads or any citywide system of public transportation.” Yet Gurgaon is a magnet for “India’s best-educated, English-speaking young professionals,” it has 26 shopping malls, seven golf courses, apartment towers, a sports stadium, five-star hotels and “a futuristic commercial hub called Cyber City [that] houses many of the world’s most respected corporations.” According to one survey, Gurgaon is India’s best city to work and live. So how does Gurgaon thrive? It thrives because in the absence of government the private sector has stepped in to provide transportation, utilities, security and more:

From computerized control rooms, Genpact [a major corporation, AT] employees manage 350 private drivers, who travel roughly 60,000 miles every day transporting 10,000 employees. Employees book daily online reservations and receive e-mail or text message “tickets” for their assigned car. In the parking lot, a large L.E.D. screen is posted with rolling lists of cars and their assigned passengers.

And the cars are only the beginning. Faced with regular power failures, Genpact has backup diesel generators capable of producing enough electricity to run the complex for five days (or enough electricity for about 2,000 Indian homes). It has a sewage treatment plant and a post office, which uses only private couriers, since the local postal service is understaffed and unreliable. It has a medical clinic, with a private ambulance, and more than 200 private security guards and five vehicles patrolling the region. It has A.T.M.’s, a cellphone kiosk, a cafeteria and a gym.

“It is a fully finished small city,” said Naveen Puri, a Genpact administrator.

…Meanwhile, with Gurgaon’s understaffed police force outmatched by such a rapidly growing population, some law-and-order responsibilities have been delegated to the private sector. Nearly 12,000 private security guards work in Gurgaon, and many are pressed into directing traffic on major streets.

Not everything works well, of course. Gurgaon is describe as a city of “private islands.” Private oases would be a better term. Within the private oases life is good but in between lies a desolate government desert. Not only are services such as roads and utilities poor, the private oases don’t internalize all the externalities so there are problems with common resources such as the water table. It would also be more efficient to have centralized sewage and electricity.

Much of the article is written as a “cautionary tale,” the private sector can’t do everything and the absence of government has made the city dysfunctional. I see the situation somewhat differently. The problem is that the original developer didn’t go far enough. The original developer, DLF, made a deal to build commercial buildings and apartments but:

… a state agency, the Haryana Urban Development Authority, or HUDA, was supposed to build the infrastructure binding together the city.

And that is where the problems arose. HUDA and other state agencies could not keep up with the pace of construction. The absence of a local government had helped Gurgaon become a leader of India’s growth boom. But that absence had also created a dysfunctional city.

Had the original developer been responsible for both the oases and the desert it could have built the power plants, the roads and other infrastructure and made locating in Gurgaon even more desirable than it is now. It is true that a city requires public goods which local governments often do not provide. Charter cities try to get around this problem by importing wholesale a new, higher-quality government. An alternative is to avoid government all together and privatize enough to make the entire city what is in effect a hotel on a grand scale.

But what to do now? The governments involved are inefficient and often corrupt. We can hope that they will get better in response to the well-educated populace and the incoming corporations but even today, the solution is not simply to hope for better government but to expand on what is working well. The firms that operate the private oases are “small cities,” the solution is to make these cities larger.

Connect enough office parks, factories, and apartments, for example, and it will make sense for a private firm to build an efficient electric plant rather than have smaller firms use inefficient and polluting diesel as is the case now. Similarly, Will Rogers once said the solution to congestion was to have business build the roads and government build the cars. In fact, only the former is necessary. Privatize the roads and they will be quickly built and well maintained (yes, they will probably be more expensive than necessary due to some monopoly power but at this point in time that is a second-order problem).

As the private oases reach out and connect with one another most of the kinks will be ironed out. The city is only thirty years old and undergoing a growth spurt, so some problems are to be expected. The big picture, however, is that a modern city has been built from the ground up based almost entirely on private development, it is attracting residents and jobs and leading the country in economic growth. A remarkable achievement.

Addendum: For more historical and contemporary examples on the private provision of public goods see The Voluntary City.

Addendum 2: Matt Yglesias gets it and then makes some interesting comments and critiques.

T-bills as a substitute for financial regulation

Let’s say that somehow — miraculously — the United States achieved a balanced budget, and furthermore assume that this did not interfere with cyclical goals. There would be many fewer T-bills, especially since the current structure of the debt is quite short-term.

Fully safe collateral would be hard to come by.

I see the paucity of safe assets, and safe collateral, as a major financial problem looking forward. Our economy desires to extend more short-term credit than we can back by ready safe collateral or that we can cover by FDIC-like insurance. Yet credit moves forward, in part because of bailout incentives but also because failed managers simply aren’t, and cannot be, punished very hard. We return to the 19th century problem of bank runs, this time on the shadow banking system, and we realize to our horror that 1934-19?? was the exceptional and now-disappeared “safe period.” We shudder to think of the next crisis, which is one reason why so many people are skittish about the Greek situation.

T-bills limit one agency problem, but create another. If there were T-bills “coming out our noses,” finance would be much safer, although of course we would have to face the moral hazard problem of what the government does with so much borrowed money. When the quantity of T-bills goes down, financial regulation becomes a tougher act to pull off.

When the Fed pays interest on reserves, cash becomes like T-bills. Interbank lending falls, because there is less need to dispense of “idle” reserves. I agree with Scott Sumner that interest on reserves is contractionary and that has had negative macroeconomic consequences. Still, I worry that if we eliminate interest on reserves, the regulation of interbank credit becomes more problematic. Much more overnight lending would go on. In essence fear of inadequate bank regulation pushed the Fed to contract in this manner.

If you want to get rid of all or nearly T-bills, you are very optimistic about bank regulation. I am not very optimistic about bank regulation.

The new preface from TGS

It is added to the print version and is available on-line from Reuters, to coincide with the publication of the physical book, which is now in stores. Excerpt:

The original publication of The Great Stagnation was in eBook form only, and I meant for that to reflect an argument of the book itself: The contemporary world has plenty of innovations, but most of them do not benefit the average household. After all, the average household does not own an eReader. It’s not even clear whether the average household buys and reads books. So I viewed the exclusive electronic publication, somewhat impishly, as an act of self-reference to the underlying problem itself. It was therefore a bit amusing when some critics suggested that the new medium of the eBook itself refuted the book’s stagnation theory—quite the contrary.

Austro-Afghanistan business cycle theory

The World Bank found that a whopping 97 percent of the gross domestic product in Afghanistan is linked to spending by the international military and donor community.

That is via Matt Yglesias, original source here. Nor was the boom that great either.

Plato visits Sicily and Siracusa

With these thoughts in my mind I came to Italy and Sicily on my first visit. My first impressions on arrival were those of strong disapproval-disapproval of the kind of life which was there called the life of happiness, stuffed full as it was with the banquets of the Italian Greeks and Syracusans, who ate to repletion twice every day, and were never without a partner for the night; and disapproval of the habits which this manner of life produces. For with these habits formed early in life, no man under heaven could possibly attain to wisdom-human nature is not capable of such an extraordinary combination. Temperance also is out of the question for such a man; and the same applies to virtue generally. No city could remain in a state of tranquillity under any laws whatsoever, when men think it right to squander all their property in extravagant, and consider it a duty to be idle in everything else except eating and drinking and the laborious prosecution of debauchery. It follows necessarily that the constitutions of such cities must be constantly changing, tyrannies, oligarchies and democracies succeeding one another, while those who hold the power cannot so much as endure the name of any form of government which maintains justice and equality of rights.

The link is here, hat tip goes to Yana.

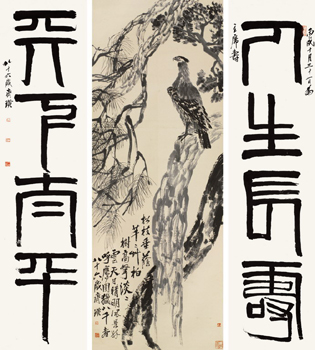

1946 Chinese painting auctions for $65 million

The story is here and hat tip goes to Felix Salmon.

Antibiotic resistance

The E coli strain that is killing people in Europe is both new and resistant to at least a dozen antibiotics in eight classes. It’s clear, therefore, that this strain picked up resistance via gene transfer from previous strains that evolved resistance over a longer time frame. Thus, antibiotic resistance can spread very quickly, probably more quickly than we can develop new antibiotics. One of the places that resistance develops is in farm animals where antibiotics are used as growth promoters, not just as therapeutics. Since there is a significant externality from antibiotic use, there is a good case to be made for regulating antibiotic use. As Glenn Reynolds once put it:

I think you can make a better case for regulating antibiotics than heroin: Misusing antibiotics can endanger countless others, while misusing heroin mostly endangers oneself.

(FYI, Tyler and I use antibiotic use as an important example of externalities in Modern Principles).

Denmark progressively regulated and reduced antibiotics for sub-therapeutic use in pigs, poultry and other livestock beginning around 1995. After some experimentation, pig production was not adversely affected and resistance in the wild declined. It’s less clear whether human health increased due to the regulation of antibiotics in farm animals (although there is less resistance in countries that use fewer antibiotics). It may be that Denmark is simply too small and connected with the rest of the world to see a large effect. Nevertheless, Denmark shows us that the costs of reducing antibiotic use in farm animals is not excessive, especially if phased-in, and the benefits of maintaining the effectiveness of our stock of antibiotics is so high that I see more intelligent but reduced use as an important goal.

See also Megan McArdle’s very good talk on this topic.

Assorted links

1. More or less the opposite of the truth. And do not confuse “hilarity with universality” with “hilarity” more generally. It is on the first that the Germans fail, not the second.

3. An argument that driverless cars are not illegal.

4. Further thoughts on declining crime rates.

5. Another ZMP laborer? Or is it sticky wages?

6. Sicilian mayor sells homes for one euro.

7. We were (are) not as wealthy as we thought, or when did the recession really start?

The furor over the new British college

Read all about it. Excerpt:

Current London students also protested that New College students would be allowed to use publicly funded facilities such as the main University of London Senate House Library in Bloomsbury.

As the anger grew, Dawkins distanced himself from the launch, while David Latchman, master of Birkbeck, released a statement making clear that Grayling had resigned from his post to lead New College.

Meanwhile, questions were raised about investors in the venture, which will be one-third owned by academics, with much of the rest of the money coming from wealthy individuals, including a manager at a Swiss private equity firm.

Addendum: Tim Worstall sends along this useful link.

Which is the more important headline?

US solar power nears competing on price (“US solar power will compete on price with conventional generation within three years without subsidy thanks to plummeting costs, industry leaders say.”)

Or:

Oil leaps as Opec descends into acrimony

Is a falling oil price a necessary concomitant of viable solar power on a large scale? Or not? Is the price of natural gas falling through the floor? I missed that headline.

I thank Jim Olds for a relevant pointer.

*Unified Growth Theory*, by Oded Galor

In one scenario, the Neolithic revolution comes earlier to some areas than others; those areas then receive their gains in the form of higher population rather than higher wages, for Malthusian reasons. Under some conditions, some of those regions manage slightly positive per capita income growth for extended periods of time (it is on this question that I find the argument both haziest and most parasitic on other theories; toward the end of the book the stress is on whether an economy has had prior selection for “quality” individuals). That can lower their birth rates, which allows for a take-off out of Malthusian constraints. There may be further positive selection for pro-economic growth humans, which compounds and extends growth.

That is not the entire unified theory but it does offer a flavor of which kinds of mechanisms do the work. There isn’t much talk of government policies, coal, or liberal ideology, although every now and then incentives and intellectual property rights appear on a list of factors relevant for growth.

The book has many equations, right in the text, but the main arguments are explained clearly with words.

I would have found it valuable if the author would have asked a concrete question: “Could the Industrial Revolution have come to Song China (Rome, Baghdad, etc.)?” and told us in terms of the parameters of his theory why or why not. I am never sure what stance he is taking on the degree of contingency in observed outcomes.

It is argued that Africa has too much genetic diversity, Native American populations too little. This seems question-begging, and I wonder if the African populations which actually came into contact with each other on a regular basis, pre-imperialism, had so much genetic diversity.

The most valuable part of the book is the extended discussion of how “time since the Neolithic Revolution” matters and how subtle and indirect the indirect mechanisms of connection can be. I consider those discussions to be a major contribution.

It’s certainly an interesting work, but most of the evidence offered is supporting the more general parts of the argument, not the more controversial or novel parts. Galor is very smart, and anyone interested in economic growth should read this book, but I would not describe myself as a convert to either the conclusions or the overall method.

Here is my previous post on the book.