Jim Gwartney, RIP

Alas…he was a great economist…

How women are perceiving the economics profession

Fewer women reported being satisfied with the climate in the economics profession in 2023 compared to five years ago, despite efforts during that time to improve conditions for women in the field, according to a new survey.

About 17% of women in economics said they strongly agreed or agreed with a statement about being satisfied in the profession, down from 20% in 2018, according to the topline results of a survey conducted in the fall. The preliminary findings were presented by University of Chicago Booth School of Business economist Marianne Bertrand Friday at the American Economic Association’s annual meeting in San Antonio.

The gap between women and men’s experience in economics widened slightly over the past five years, with 39% of men saying they were satisfied with the profession’s climate, compared to 40% in 2018.

Women made up just 17.8% of full economics professors in 2022. While representation is higher among students and associate professors, the share of new economics doctoral degree recipients that were women fell in 2023, Bertrand said Friday.

Sunday assorted links

The culture that was East German

This paper studies important determinants of adult self-control using population-representative data and exploiting Germany’s division as quasi-experimental variation. We find that former East Germans have substantially more self-control than West Germans and provide evidence for government surveillance as a possible underlying mechanism. We thereby demonstrate that institutional factors can shape people’s self-control. Moreover, we find that self-control increases linearly with age. In contrast to previous findings for children, there is no gender gap in adult self-control and family background does not predict self-control.

That is from the Economic Journal by Deborah A Cobb-Clark, Sarah C Dahmann, Daniel A Kamhöfer, and Hannah Schildberg-Hörisch, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Kamil Kovar on the German debt brake (from my email)

I was wondering if you would consider writing a post about the German debt brake in light of recent developments? Personally, I am not a huge fan of discussions about fiscal policy (or even worse, austerity…), as I feel they are mostly Rorschach test without much deep thinking. But I did find the recent developments intriguing because they challenge my priors so I am wondering what whether your thinking has changed as well.

My prior was that some form of constitutional debt break is a reasonable mechanism to deal with the pro-debt bias resulting from democratic political process. Of course, some of the recent German experience has challenged that. For example, debt break legislation lead to a lot of “bad” legislating, which was exposed by the court recently. Similarly, the debt break is leading Germany to cut spending and increase taxes relative to what the government would want; given the weakness in German economy this does not seem like optimal fiscal policy (but might be – monetary policy by choice restrictive, and many have called on fiscal to be too). And more broadly, there is a fair argument to be made that it has constrained government investment during last decade, which was an optimal time to do government investment given the negative interest rates.

Part of this I think is a question of imperfect design/implementation. The deficit threshold of -0.35% is higher than I would imagine. Absence of any relationship to current interest rates or effect on future debt levels ala CBO analysis is probably not what finance theory would suggest. And the cyclical adjustment seems suspicious: my understanding is that currently the cyclical adjustment allows for 0.1% of GDP of extra deficit, corresponding to 1% output gap and 1/10 elasticity, see here.[1] But I suspect imperfect design/implementation will always be a feature of these kind of legalistic rules, so should not be waved away.

At the same time, I find lot of the commentary rather subpar. I have in mind for example arguments in this article. While I can see that investment would likely be higher last decade in absence of debt break, saying that debt break results in “Germany that doesn’t invest and massively falls behind in economic terms” is just shocking, as it implies that investment can be only done through higher deficits. Moreover, arguing that debt break has to be abolished so that Germany can invest to deal with geopolitics and green transition is simply ignoring that Germany already found a legally-sound solution to such kind of problems when it constitutionally created its 100 billion euro defense spending fund. Together with the wise use of debt break suspensions during last 4 years this shows that there is sufficient flexibility built into this, despite what the commentators would suggest (“but in practice it’s too inflexible”), as long as there is consensus on such actions. But maybe this points towards the actual problem: maybe in current society building political consensus has become too hard, so that mechanisms which rely too much on such consensus are doomed to create more problems than their benefit. The US debt ceiling comes to mind. Similarly, I think CDU secretly agrees with some of the governments desires, but will not act on them either because it wishes for the government to collapse or is afraid of voters’ reaction.

Very curious what is your thinking and how it has changed.

Kamil

P.S.: Relatedly, I often see left-of-center economists citing IMF research that austerity does not yield decrease in government debts relative to GDP. While I understand the value of such research, I am not sure what are the people suggesting. If austerity cannot lower debt to GDP, what can? I don’t think that most economists would suggest that large scale government investment is going to lower debt to GDP. So it the conclusion that we can never lower debt to GDP?

Kamil expands on these points in a blog post, concluding:

So maybe this is the main critique of the constitutional debt break: In the older world it might have been an good tool, but given the general unravelling of political process around the world, it adds too much of a constraint leading to worse outcomes. It simply is not fit for the current times. It might not be. As for me, I am currently in state of “not sure”.

What I’ve been watching

Poor Things created a visual and stylistic and historical world all of its own. Not a perfect movie by any means, but entrancing throughout. I took the central idea to be why (different kinds of) men are attracted to autistic women, but I do understand no one else saw it that way.

American Fiction I soured on. I guess I don’t get enough jollies from making fun of the Wokies, because the movie didn’t add to my understanding and just made them stupid targets. I can (and do) get that on Twitter any day. Some people will really like this one, but I wouldn’t have minded missing it.

Anselm 3-D is excellent if you know a lot about Kiefer, various German Kriegsauseinandersetzungen, and if you want a look into art production in factory settings. I meet all three of those standards, and then some.

Saturday assorted links

1. Flowers are evolving (rapidly) to have less sex (NYT).

2. Europe’s political stupor, excellent essay by Leopold Aschenbrenner.

4. Horse cloning transforms polo in Argentina. “Using embryo transfers, a single horse can now give birth to as many as 10 foals per year, instead of one…”

5. Model this (NYT): “Maine at Augusta spent $15,225 last year for the right to market U.S. News “badges” — handsome seals with U.S. News’s logo — commemorating three honors: the 61st-ranked online bachelor’s program for veterans, the 79th-ranked online bachelor’s in business and the 104th-ranked online bachelor’s.”

6. Mexican drone attack kills 30 in Guerrero (in Spanish).

Okie-dokie…

US Intelligence Shows Flawed China Missiles Led Xi to Purge Army

China missiles filled with water, not fuel: US intelligence

And:

…vast fields of missile silos in western China with lids that don’t function in a way that would allow the missiles to launch effectively

Here is more from Bloomberg.

My history of economic thought reading list

History of Economic Thought syllabus

The honor code applies to this class. Accommodations will be made for disabilities in accord with the policies of George Mason University.

Your grade is 2/3 based on your paper, 1/3 based on a final exam. You are required to submit short progress reports on your paper on a regular basis.

Reading list:

Commerce, Culture, & Liberty: Readings on Capitalism Before Adam Smith, edited by Henry C. Clark.

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations.

Tyler Cowen, GOAT: Who is the Greatest Economist of all Time, and Why Does it Matter?, free and on-line.

GPT-4, paid version, mandatory, $20 a month.

Phind (free, good for giving you reliable references)

Perplexity.AI, free, usually better than Google these days

The internet

I will assign other readings, predominantly on-line, depending on the topics we end up covering.

The economic returns to psychological interventions

That is the topic of my Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

One study of Ethiopia looked at the psychological impact of raising aspirations. The researchers created a randomized control trial, showing one group of people short films about business and entrepreneurial success in the community. Six months later, those who had seen the films had worked more, saved more and invested more in education, relative to those who had not seen the films. Even five years later, households that had seen the films had accumulated more wealth, and their children had on average 0.43 more years of education, which typically is considered an impressive effect.

Not all the results are so positive:

Sometimes psychological interventions produce only temporary effects. One research design taught self-efficacy lessons to women in India. The likelihood of employment rose 32% in the short run — but within a year the effects had dissipated…

None of these results demonstrates that there is a “psychology of poverty” to be overcome by external interventions. They do imply, however, that poorer economies can make marginal gains by investing in what might be called psychological and psychotherapeutic infrastructure. These research designs can be applied to hundreds or thousands of people, but it will never be easy to use them for entire citizenries. Nonetheless, countries can make therapeutic help more accessible and affordable, and foster a culture in which people feel comfortable seeking it out.

Are we in the west at the margins where more counseling and therapy are of zero value, or perhaps negatives? Perhaps the only choice is either to have too little or too much self-reflection of a particular kind.

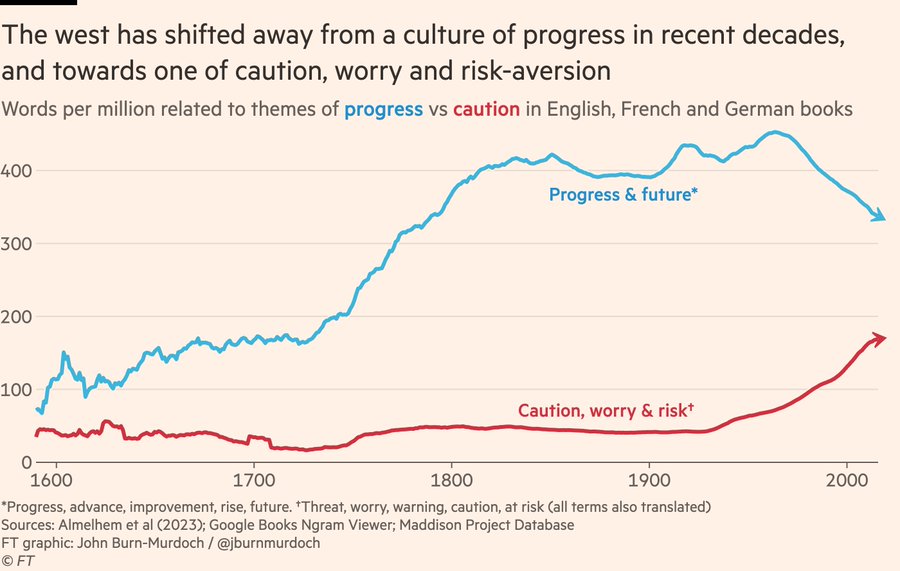

We need more talk of progress

Here is the underlying John-Burn Murdoch FT piece, pointer here. And a text excerpt:

Ruxandra Teslo, one of a growing community of progress-focused writers at the nexus of science, economics and policy, argues that the growing scepticism around technology and the rise in zero-sum thinking in modern society is one of the defining ideological challenges of our time.

I am pleased that Ruxandra is now also an Emergent Ventures winner.

Friday assorted links

1. Problems with U.S. shipyards.

2. Satellite imaging shows there is a lot more industry in the ocean than we had thought.

3. My podcast episode with Will Bachman, most of all about talent see also the Show Notes at the link.

4. Bravo NYT, glad they signaled their intent was not to insult my intelligence.

5. Straussian Taylor Swift? (NYT)

6. Scott Sumner movie and book reviews, he also has perfect taste in fiction.

Predictions for 2024

Bari Weiss interviews myself, Niall Ferguson, John McWhorter, Peter Attia, Nate Silver, and others about the year to come. I am not so pessimistic!

*You Will Not Stampede Me: Essays on Non-Conformism*

That is the new book by my colleague Bryan Caplan, collected largely from his previous blog writings. Bryan emails to me:

I just released a new book of essays on Amazon, entitled *You Will Not Stampede Me: Essays on Non-Conformism*. Emerson and Thoreau were right: Excessive conformity is a major impediment to living a full life in the modern world, and you really can improve a lot with modest effort.For details, see my recent Substack.…Like my other books of essays, You Will Not Stampede Me is divided into four parts.

- The first, echoing Milgram, is “Disobedience to Authority.” These pieces dissect the psychology and economics of being normal.

- The next section, “The World Is Wrong,” explores big, specific issues where the popular opinion sucks. Covid, of course, but also bioethics, trolling, the right of revenge, and more.

- I follow with “The Weird Is Right,” most notably with the essay, “A Non-Conformist’s Guide to Success in a Conformist World.” Yes, the world does punish non-conformists, but so sporadically and thoughtlessly than the crafty can usually defy the world with impunity.

- I close the book with “Non-Conformist Candor,” where I call a litany of hand-picked controversies just like I see them.

As usual with my books of essays, you can read them all for free in the Bet On It Archives. What you get for your $12 is curation, convenience, and coolness.

As you might expect, I like to troll Bryan by telling him he is a deeply conformist suburban Dad, in the good sense of course. Read this book and find out if I am right or not.

My podcast with Brink Lindsey

He is starting a new podcast and I am perhaps the first episode? There is video and text and audio. Here is an excerpt:

Lindsey: Did they recognize early on that you were different and that they had a job to do to push you, or no?

Cowen: Well, my father thought I was weird, so he thought I was different, but it would’ve been easier for him if I had, say, been a football player in the way that he was captain of his high school football team. He accepted what I became but I was not obviously doing things he had done. My mother was very open-minded. But when I was quite young, I’m not even sure how young, she took me repeatedly to the public library. At first, it was a Carnegie library in the town of Kearney, New Jersey, but later to Bergen County libraries. And without those library trips, I would’ve been very different. And then my father’s mother, my grandmother, lived with us for a while and she taught my sister how to read. And I was about two and I learned by looking over her shoulder. And so my grandmother had to big influence on me. And my grandmother loved to read. She loved Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, John O’Hara, and also liked Ayn Rand even though she was not a partisan of any one of those things. So my grandmother too was a real influence.

And:

Lindsey: You’re now known for your incredible diversity of intellectual interests. Was that from the start? Did your curiosity just naturally pull you in a million different directions, or was there some point where you recognized, “Hey, my specialty is breadth and I need to lean into that”?

Cowen: Well, I think when I was quite young, I was much more conservative in the small-c sense of that word. I didn’t have an interest in traveling. I was more reserved. If you’re a chess player when you’re a kid, that’s extremely narrow. And that was the main thing I did with a bit of science fiction. So the breadth, I think, came gradually and most of all in my very late teens with classical music, beginning to travel. So I don’t think it was in me at the beginning in any obvious way.

Lindsey: But it came out in adolescence?

Cowen: Yes. But someone looking at me at age seven would not have predicted breadth later on.

Interesting throughout…and do subscribe to Brink’s Substack.