Words of Wisdom from Robert Shiller

Strategic default on mortgages will grow substantially over the next

year, among prime borrowers, and become identified as a serious

problem. The sense that ‘everyone is doing it’ is already growing, and

will continue to grow, to the detriment of mortgage holders. It will

grow because of a building backlash against the financial sector,

growing populist rhetoric and a declining sense of community with the

business world. Some people will take another look at their mortgage

contract, and note that nowhere did they swear on the bible that they

would repay.

From the WSJ's Real Time Economics.

The economics of advice

At times I believe the following propositions, in appropriately qualified fashion:

1. You don't know what a person really thinks until you hear his or her advice. Along these lines, if you really want to know what a person thinks, ask for advice and he or she will open up.

2. In philanthropy there is a saying: "Ask for money and you will get advice. Ask for advice and you will get money."

3. There are many exacting scholars who should be locked in a room, asked for advice of various kinds, and forced to speak into a tape recorder with no edits allowed. The advice-giving mode mobilizes insights which otherwise remain dormant, perhaps for fear of falsification or ridicule or of actually influencing people. All of the transcripts should be put on The Advice Website, with an open comments section, to limit the actual influence of the advice. Some famous people would be revealed as foolish in critical regards. The contents would be most interesting as non-advice and the site would carry a government warning that the advice is not to be taken seriously.

4. Often we do not trust people until we hear their advice. We suspect in any case that they wish to control us, and until we know what they have in mind, we remain wary. Sometimes it is necessary to give advice — even pointless advice — to establish trust.

These remarks are not intended to apply to medical or clinical advice.

Here is Bryan Caplan, offering direct advice to his colleagues (an excellent post). Brett Arends questions whether you should take advice from people who write for a living.

Daron Acemoglu on the U.S.-Mexican border

Via Arnold Kling, Acemoglu writes:

On one side of the border fence, in Santa Cruz County, Arizona, the median household income is $30,000. A few feet away, it's $10,000….The key difference is that those on the north side of the border enjoy law and order and dependable government services — they can go about their daily activities and jobs without fear for their life or safety or property rights. On the other side, the inhabitants have institutions that perpetuate crime, graft, and insecurity.

With apologies to Douglass North, I am rarely happy with this kind of explanation. First, are the bad institutions cause or effect? Most likely we need a framework which allows them to be both.

Second, I want the theory to also explain the (quite large) difference between the truly poor Chiapas and the relatively wealthy northern Mexico. By many metrics northern Mexico is more corrupt than Chiapas (there is more to be corrupt over, for one thing, plus drug routes play a role) and it very likely has higher rates of violent crime. In general I prefer theories which explain three data points to theories which explain two. Chiapas, of course, isn't some weird outlier which I pulled out of a hat; it's in the same country as northern Mexico and many people from that region have populated both northern Mexico and Arizona for that matter. I could have picked many other parts of Mexico as well.

One factor is positive selection into northern Mexico, on grounds of ambition and desire for higher wages. Another factor is that northern Mexican norms are (partially) geared to support American multinationals and these norms have spread more generally, including to Mexican enterprises in the region.

On another point, as I get older, I tend to view "family structure which encourages an obsession with education" as an increasingly important variable for explaining levels in per capita income, if not always growth rates in the immediate moment. It's not a truly independent variable — when it comes to growth what is? — but it's one good place to start. It helps explain why the Soviet Union, after decades of state fascism/communism, slid into a living standard higher than that of much of Latin America. It explains quite a bit of Arizona vs. Mexico but less of northern Mexico vs. Chiapas. Acemoglu mentions education in his article, but he seems to view it as resulting from instiutions rather than causing them.

I don't buy into the genetic explanations but still I view "family structure which encourages an obsession with education" as very hard to replicate through policy. Emmanuel Todd's The Causes of Progress has many problems, but it is an under-mined book when it comes to the causes of both liberty and economic growth.

Assorted links

1. Ask Felix Salmon anything, via Chris F. Masse.

2. Brad DeLong on studying heterogeneous capital.

3. Where does Chinese inflation go?

4. Via Felix Salmon, very good Sana'a image.

Markets in everything, South Korean faux funeral edition

Jung, a slight 39-year-old with an undertaker's blue suit and a

preacher's demeanor, is a resolute counselor on the ever-after who

welcomes clients with the invitation, "OK, today let's get close to

death."Jung runs a seminar called the Coffin Academy, where,

for $25 each, South Koreans can get a glimpse into the abyss. Over four

hours, groups of a dozen or more tearfully write their letters of

goodbye and tombstone epitaphs. Finally, they attend their own funerals

and try the coffin on for size.In a candle-lighted chapel, each

climbs into one of the austere wooden caskets laid side by side on the

floor. Lying face up, their arms crossed over their chests, they close

their eyes. And there they rest, for 10 excruciating minutes."It's

a way to let go of certain things," says Jung, a former insurance

company lecturer. "Afterward, you feel refreshed. You're ready to start

your life all over again, this time with a clean slate."Across

South Korea, a few entrepreneurs are conducting controversial forums

designed to teach clients how to better appreciate life by simulating

death. Equal parts Vincent Price and Dale Carnegie, they use mortality

as a personal motivator for a variety of behaviors, from a healthier

attitude toward work to getting along with family members.Many

firms here see the sessions as an inventive way to stimulate

productivity. The Kyobo insurance company, for example, has required

all 4,000 of its employees to attend fake funerals like those offered

by Jung.

The full article is here and I thank Kaylin Wainwright and Daniel Lippman for the pointers. Here is an earlier MR post on how contemplating mortality changes your behavior.

The charity tax

The estimated social pressure cost of saying no to a solicitor is $3.5 for an in-state charity and $1.4 for an out-of-state charity. Our welfare calculations suggest that our door-to-door fund-raising campaigns on average lower utility of the potential donors.

That's from Stefano DellaVigna, John List, and Ulrike Malmendier. You'll find an ungated copy here.

Soviet Growth & American Textbooks

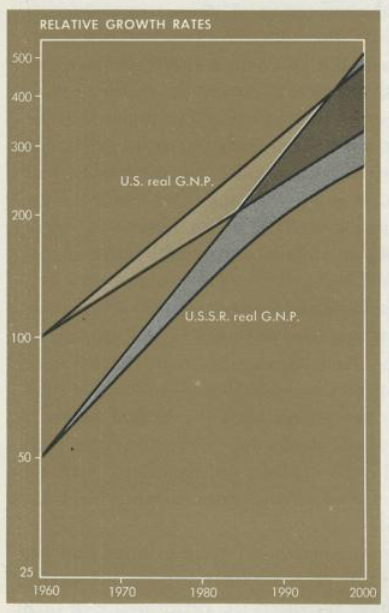

In the 1961 edition of his famous textbook of economic principles, Paul Samuelson wrote that GNP in the Soviet Union was about half that in the United States but the Soviet Union was growing faster. As a result, one could comfortably forecast that Soviet GNP would exceed that of the United States by as early as 1984 or perhaps by as late as 1997 and in any event Soviet GNP would greatly catch-up to U.S. GNP. A poor forecast–but it gets worse because in subsequent editions Samuelson presented the same analysis again and again except the overtaking time was always pushed further into the future so by 1980 the dates were 2002 to 2012. In subsequent editions, Samuelson provided no acknowledgment of his past failure to predict and little commentary beyond remarks about “bad weather” in the Soviet Union (see Levy and Peart for more details).

Among libertarians, this story has long been the subject of much informal amusement. But more recently my colleague David Levy and co-author Sandra Peart have discovered that the story is much more interesting and important than many people, including myself, had ever realized.

Among libertarians, this story has long been the subject of much informal amusement. But more recently my colleague David Levy and co-author Sandra Peart have discovered that the story is much more interesting and important than many people, including myself, had ever realized.

First, an even more off-course analysis can also be found in another mega-selling textbook, McConnell’s Economics (still a huge seller today). Like Samuelson, McConnell estimated Soviet GNP as half that of the United States in 1963 but he showed that the Soviets were investing a much larger share of GNP and thus growing at rates “two to three times” higher than the U.S. Indeed, through at least ten (!) editions, the Soviets continued to grow faster than the U.S. and yet in McConnell’s 1990 edition Soviet GNP was still half that of the United States!

A second case of being blinded by “liberal” ideology? If so, Levy and Peart throw another curve-ball because the very liberal even “leftist” texts of the time, notably those by Lorie Tarshis and Robert Heilbroner did not make the Samuelson-McConnell mistake.

Tarshis and Heilbroner were more liberal than Samuelson and McConnell but offered a more nuanced, descriptive and tentative account of the Soviet economy. Why? Levy and Peart argue that they were saved from error not by skepticism about the Soviet Union per se but rather by skepticism about the power of simple economic theories to fully describe the world in the absence of rich institutional detail.

To make their predictions, Samuelson and McConnell relied heavily on the production possibilities frontier (PPF), the idea that the fundamental tradeoff for any society was between “guns and butter.” Thus, in the 1948 edition Samuelson wrote:

The Russians having no unemployment before the war, were already on their Production-possibilities curve. They had no choice but to substitute war goods for civilian production-with consequent privation.

Note that Samuelson assumes all countries and economic systems are efficient (the Russians are “on” the curve) only the choice of guns versus butter differs. When the war ended, the fundamental tradeoff became one between investment and consumption and since the Soviets invested a greater share of GNP they would naturally consume less but grow faster. Moreover, since the Soviet’s had solved the unemployment problem they were, if anything, more efficient than the U.S. (here we see the Keynesian influence).

Levy and Peart conclude that although ideology may have played a role what arguably made a bigger difference was the blindness imposed by chosen tools. As they write:

We are all constrained by means of models: we gain insight in one dimension by blinding ourselves to events in other dimensions. Competition among models may be necessary to insure that the benefits of the models exceeds their cost.

(Applications to the financial crisis are apposite.)

Addendum: Bryan Caplan also comments. As Bryan notes, a very good economist can use PPFs and still get the story right.

Price discrimination

The founder said he had heard of Cubans practically making a living by buying and selling items through Revolico. A regular customer said he bought Windows 7 from the site for about $5. After calling the number in the Revolico advertisement, a young man showed up at his front door and installed the pirated software on his home computer.

The article, which focuses on on-line black markets for Cubans, is interesting throughout.

My visit to Yemen

With Yemen in the news I thought I would recount my trip to the country in 1996 or so. I spent five or six days in Sana'a, the capital, and I remember the following:

1. At the biggest and best hotel in town, no one spoke English or any other European language.

2. Most of the women wore full veils. This allows them to stare at foreign men, and make lots of direct eye contact, without repercussion. The younger girls looked like this. I've never been stared at more in my life, by women.

3. Virtually all of the men carried daggers in their sashes.

4. Most of the people seemed to get stoned — every day, all day long — by chewing qat. I recall reading that qat supply amounts to about 20 percent of the economy. This estimate suggests that three-quarters of the adult population partakes in the habit, every afternoon.

5. The country has the most amazing architecture I have seen, anywhere.

6. The best restaurant served fish doused in red chilies, with a vaguely Ethiopian spice palate for the other dishes. You eat with your fingers.

7. Most of the people lived what was still a fundamentally medieval existence in a medieval setting. The center of town felt like how I had imagined the year 1200 in Baghdad.

8. Yemen has perhaps the biggest problems with water supply, and vanishing aquifers, of any country. Qat cultivation makes these problems worse and for many years Yemeni government policy subsidized water extraction.

9. At the time the capital city was quite safe, though German tourists would get kidnapped in the countryside on a regular basis. The Yemenis had a reputation as very hospitable kidnappers. Usually the kidnappers would hold the tourists in return for promises about infrastructure.

10. I was accompanying a World Bank mission and had access to "the government driver" (singular), and a Mercedes-Benz. He did not speak any English or any other language besides Yemeni Arabic.

11. With the possible exception of the Bolivian altiplano, Yemen is the weirdest country or region I have visited.

12. The last decade has not, overall, been a good one for Yemen.

13. In the fall the climate was very nice.

“Fruitful Decade for Many in the World”

My NYT column today is about how good the last ten years have been for China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, and much of Africa. It is not, as Time magazine has suggested, the worst decade in human history. Here is a brief excerpt:

One lesson from all of this is that steady economic growth is an underreported news story – and to our own detriment. As human beings, we are prone to focus on very dramatic, visible events, such as confrontations with political enemies or the personal qualities of leaders, whether good or bad. We turn information about politics and economics into stories of good guys versus bad guys and identify progress with the triumph of the good guys. In the process, it’s easy to neglect the underlying forces that improve life in small, hard-to-observe ways, culminating in important changes.

Here is Alex's earlier post on African success in the decade. In addition to growth statistics, I see much of the developing world as having demonstrated a much higher than expected level of social and political cohesion. Excerpt:

Since 2007, according to Goldman Sachs, the biggest emerging markets–Brazil, Russia, India and China–have accounted for 45% of global growth, almost twice as much as in 2000-06 and three times as much as in the 1990s.

Arnold Kling notes: "Even in the United States, the fact that people are living healthier longer represents an improvement above and beyond the GDP statistics."

I did not have enough space to discuss the question of growth rates versus per capita growth rates, but here are a few relevant points:

1. Babies are pretty cheap to feed. In the short run, if your economy grows, and at the same time produces more infants, the adults are still better off.

2. In the longer run, developing countries are making the "demographic transition" quicker and more dramatically than had been expected. Mexico is an extreme example of this more general point. So if you are very worried about overpopulation (not my view), there still has been plenty of good demographic news in the last decade. Economic growth in the developing world will not be "swallowed up" by rising population.

3. "More children" can be a legitimate way for a country to enjoy higher living standards.

4. Social indicators such as water and sanitation in households are generally higher in the afore-cited countries, over the last decade. That's further evidence for #1.

Again, I'd like to stress the general point that most American-born economists are not sufficiently cosmopolitan in their thinking and writing.

Assorted links

1. Is Somali pirate cash causing a Kenyan property boom?

2. What is the hardest language?

3. Markets in everything: how hackers check their work on viruses.

4. Has the anti-foreclosure program done more harm than good?

5. National and cultural differences in cell phone usage.

Advice for your children: 2010-2020

Chug asks:

I'm curious what kind of advice you're giving Yana (as the proxy for "college age people") about the next 5 to 10 years regarding debt, investing, jobs, etc. Not Yana-specific advice, but general young-person advice for the 2009-2019 period.

My first-order response is that my most important advice comes by example and I have little idea what kind of message is actually being received. Keep in mind that children often respond to your strengths with niche-finding strategies, and thus deviation, rather than copying strategies.

Otherwise, a long time ago I told Yana to take calculus and statistics; even if she hates them she'll know what side of that divide she stands on. I am encouraging of learning languages, driving modest Japanese cars, and ordering the most unappealing-sounding dish on the menu of a good restaurant. On investing it's buy and hold all the way. Use TimeOut guides when you travel and when you are eating in third world countries avoid walls. I'm not a big fan of debt; debt is worth it only if you're earnings-obsessed and I don't recommend that for most people. Don't expect to be too happy, that is counterproductive. I've mentioned that future job descriptions may be quite fluid and unpredictable from today's vantage point. Being "good with people," combined with smarts and a focus on execution, will never wear out. The reality is that I hardly have any useful advice.

Do you?

Assorted Movie Links

- Larry Ribstein on How Movies Created the Financial Crisis.

- A perceptive review of Avatar. The best graf:

…[T]he more blatant lesson of Avatar is not that American imperialism is bad, but that in fact it’s necessary. Sure there are some bad Americans–the ones with tanks ready to mercilessly kill the Na’vi population, but Jake is set up as the real embodiment of the American spirit. He learns Na’vi fighting tactics better than the Na’vi themselves, he takes the King’s daughter for his own, he becomes the only Na’vi warrior in centuries to tame this wild dragon bird thing. Even in someone else’s society the American is the chosen one. He’s going to come in, lead your army, fuck your princesses, and just generally save the day for you. Got it? This is how we do it.

- And finally. this is not a good way to open the NYSE.

The economic theories of the MLA

A resolution calling for full- and part-time faculty members to “be eligible for tenure” and expressing the view that “[a]ll higher education employees should have appropriate forms of job security, due process, a living wage and access to health care benefits” passed in a 81-15 vote, but not without concerns from delegates that the wording went too far – or not far enough.

Ian Barnard, an associate professor of English at California State University-Northridge, said he wanted to see the resolution extended to include a call for all faculty to be eligible not only for tenure but also for full-time employment. Simply voicing support for a lecturer to continue to be guaranteed one course per semester was, he said, “really weak … a way for us to cop out,” for departments to avoid paying for health benefits and for adjunct faculty to continue bouncing around among many jobs just to make ends meet.

The full story is here. Why don't journalists demand something similar? You can pinch yourself, but it really is 2010.

By the way, here are some facts:

In 1960, 75 percent of college instructors were full-time tenured or tenure-track professors; today only 27 percent are.

Terrorists and false positives

Matt Yglesias calculates:

…monitoring the UK’s 1.5 million Muslims is a lost cause. If you have a 99.9 percent accurate method of telling whether or not a given British Muslim is a dangerous terrorist, then apply it to all 1.5 million British Muslims, you’re going to find 1,500 dangerous terrorists in the UK. But nobody thinks there are anything like 1,500 dangerous terrorists in the UK. I’d be very surprised if there were as many as 15. And if there are 15, that means you’re 99.9 percent accurate method is going to get you a suspect pool that’s overwhelmingly composed of innocent people. The weakness of al-Qaeda’s movement, and the very tiny pool of operatives it can draw from, makes it essentially impossible to come up with viable methods for identifying those operatives.