Minimum Wage Review

David Neumark has a good review of the minimum wage literature for a popular but intelligent audience.

Typepad comments

Sometimes it shows up on the blog that there are zero comments, but of course MR readers have more to say than that. Don’t be fooled by this recurring glitch in Typepad.

MR readers also have complained that when writing comments, the right side of the line runs into the ads and is impossible to read when editing. Do any of you have useful suggestions for addressing this problem?

Why don’t redistributionists like big band music?

Gabriel Rossman writes to me:

A few days ago there was a discussion on this blog about the book Conservatize Me and more broadly, about taste and politics. Many of the questions can be answered systematically since in 1993 the General Social Survey included a list of questions about musical taste. The simplest question to ask is how different types of music correlate with ideology (polviews). Generally speaking, the stereotypes hold up. Country is correlated with the right whereas classical, rap, rock music, and heavy metal are all correlated with the left. Opinions about folk music aren’t correlated with politics. Note though that even the strongest correlations are relatively weak (r<0.20) so there are plenty of liberals out there listening to country and no shortage of conservative rap fans.

Another way to look at it is to break politics into two dimensions. Let’s treat whether the government should reduce income differences (eqwith) as a measure of economic attitudes. Folk, classical, and big band music are very unpopular with redistributionists. (I guess nobody dreamt about Joe Hill the night before the survey). Rap, metal, and blues are popular with redistributionists. Country, rock, and bluegrass aren’t correlated with fiscal attitudes. For social attitudes, let’s use opinion of sex before marriage (premarsx). Folk, country, classical, bluegrass, and big band fans tend to disapprove of fornication, whereas rap, rock, metal, and blues fans think it’s fine. (If you substitute gay sex for premarital sex the pattern is the same, except for rap fans who tend to oppose it). I experimented with looking for distinctively "libertarian" taste patterns but couldn’t find any.

This is all back of the envelope stuff. A more sophisticated analysis would use factor analysis on dozens of attitudinal questions and find corresponding patterns in them.

You can find the 1993 GSS at Princeton’s Cultural Policy and Arts National Data Archive. http://www.cpanda.org/codebookDB/sdalite.jsp?id=a00006. There’s a self-explanatory web engine that allows you to compare any two variables. (Want to know how many opera fans have been in fist fights? Or how people who have paid for sex feel about nuclear power? Now is your chance.) More advanced users can download the full dataset in SPSS, ASCII, or CSV and do whatever they want with it.

Gabriel Rossman is very smart. Here is his home page. Here is a summary of his dissertation. Here is an abstract of his paper on the Dixie Chicks and where they received less play time. Here is his paper on "Who Picks the Hits on Radio"?

Addendum: Here is Benny Goodman on YouTube. Here is Stan Kenton. Here is Count Basie. I could give you more.

Race and Culture

The NYTimes reports that in Queens the median income for blacks is above the median income for whites, the only large county in the nation for which that is true. The median income for blacks in Queens, $51,836, is also well above the national median income ($46,000).

What makes the statistics especially interesting is that many of the blacks in Queens are recent immigrants from the West Indies. Malcolm Gladwell, whose own genealogy traces to the West Indies, recognizes the implication:

The implication of West Indian success is that racism does not really

exist at all–at least, not in the form that we have assumed it does.

The implication is that the key factor in understanding racial

prejudice is not the behavior and attitudes of whites but the behavior

and attitudes of blacks–not white discrimination but black culture. It

implies that when the conservatives in Congress say the responsibility

for ending urban poverty lies not with collective action but with the

poor themselves they are right.

but ultimately he can’t accept the implication and offers instead a strained interpretation. West Indian blacks are successful only because, according to Gladwell, they provide a convenient way for whites to distinguish "good" and "bad" blacks allowing themselves to pat themselves on the back for not being racist while at the same time continuing to practice racism against the majority black class.

Gladwell offers scant evidence for his hypothesis, the most interesting point being his claim that Jamaican blacks are perceived as bad citizens in Toronto where they are dominant but as good in New York where they can define themselves in opposition to American blacks. Gladwell’s argument is weak, however, because West Indian blacks distinguish themselves not just in dress or accent but in just those behaviors that also increase income for whites and other successful minorities: they get married and stay married, pursue education, work hard and are entrepreneurial. Gladwell himself notes:

When the first wave of Caribbean immigrants came to New York and

Boston, in the early nineteen-hundreds, other blacks dubbed them

Jewmaicans, in derisive reference to the emphasis they placed on hard

work and education.

The title of the post refers of course to Thomas Sowell’s classic.

What I’ve been reading

1. The Naked Brain: How the Emerging Neurosociety is Changing How We Live, Work, and Love, by Richard Restak. A good summary of a bunch of results I already knew, but a suitable introduction for most readers. It doesn’t cover neuroeconomics.

2. Light in August, by William Faulkner. I am rereading this, wondering whether I should use it for my Law and Literature class in the spring. My memory was that this is the "easy" classic Faulkner but the text is tricker than I had remembered. Not quite as good as As I Lay Dying or Absalom, Absalom.

3. Matthew Kahn, Green Cities: Urban Growth and the Environment. From Brookings, a good and balanced treatment of the intersection between environmental and urban economics. Here is Matt’s blog.

4. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion. I’m still at p = .05, if only because I fear such a heavy reliance on the anthropic principle. This book didn’t sway me one way or the other. And while I am not religious myself, I am suspicious of anti-religious tracts which do not recognize great profundity in the Bible. Furthermore, as Dawkins recognizes, civilization requires strong loyalties to abstract principles; I’m still waiting to see a list of the relevant contenders to choose the best. Here is Dawkins speaking.

5. Michael Lewis, The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game. I loved Liar’s Poker and Moneyball but this one did not grab me at all. I stopped. Perhaps the reader needs to love football. Here is a radio interview with the author. Here is his NYT article.

How has the Swedish welfare state survived?

…the Scandinavian welfare states have an above average growth record during the period 1970-2000: Sweden has to some extent lagged behind, but Finland and especially Norway have grown steadily.

Andreas Bergh offers two answers: First, if we look at measures of economic freedom, especially those measures which track freedom independent from the size of government expenditures, the Scandinavian countries have become much freer. (Note that the Netherlands, which until very recently was outperforming the other European welfare states, experienced the greatest gains in this category.)

Second, the Scandinavian economies have become much more globalized. The old story was that globalization rendered welfare state expenditures unsupportable; it is more likely that the opposite is true, at least provided trade is open, credibility is high, and business regulation is light.

I wish this paper were 100 rather than 20 pages, but I believe the author is on to something very important.

Addendum: Here are other versions of the link to the Bergh paper, if the given link is still down.

We are Iran

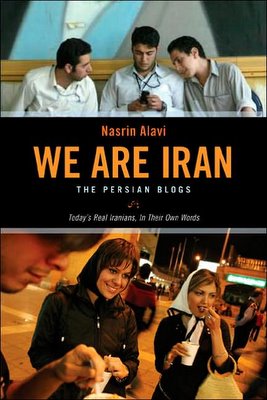

Here is the UK cover for a book on Iranian bloggers:

Your screen is OK, the image has lots of white space. Here is the US cover of the same book:

Are U.S. covers in general more literal? Here is the the source; the fascinating blog is devoted to discussing book covers. Here is the UK-US comparison for David Mitchell’s excellent Cloud Atlas. Here is the Turkish cover of Freakonomics. Here is an iPod ad from the Czech Republic.

Live as a conservative?

- Charlie Daniels Band—Essential Super Hits of Charlie Daniels Band

- Clint Black—Greatest Hits II

- Craig Morgan—Craig Morgan

- Daryl Worley—Have You Forgotten?

- Kid Rock—Devil Without a Cause

- Lee Greenwood—American Patriot

- Michael W. Smith—Healing Rain

- Toby Keith—Unleashed

Movies:

The link is from Jason Kottke.

The saga continues

According to Chessbase.com, a chess news Web site, at the start of today’s game, Mr. Topalov sat down to play while Mr. Kramnik went to his private area and sat down outside his private bathroom, demanding that it be unlocked.

Chessbase reported that the organizers refused his request and after an hour, the game was declared forfeited in Mr. Topalov’s favor.

Here is one story.

Moscow 1941

When the storm broke, people turned to Tolstoy: "During the war," wrote the critic Lidia Ginzburg, "people devoured War and Peace as a way of measuring their own behavior (about Tolstoy they had no doubt: his response to life was wholly adequate). The reader would say to himself: Well then, so what I am feeling is right: that’s just how it should be." War and Peace was the only book the writer Vasili Grossman had time to read while he was a frontline correspondent, and he read it twice. It was broadcast on Moscow Radio, complete, over thirty episodes.

That is from new and noteworthy Moscow 1941: A City and its People at War, by Rodric Braithwaite, recommended.

Markets in deaf embryos

What do you think of this? Consumer sovereignty anyone?

Several U.S. fertility clinics admit they’ve helped couples deliberately select defective embryos. According to a new survey report, "Some prospective parents have sought [preimplantation genetic diagnosis] to select an embryo for the presence of a particular disease or disability, such as deafness, in order that the child would share that characteristic with the parents. Three percent of IVF-PGD clinics report having provided PGD to couples who seek to use PGD in this manner." Since 1) the United States has more than 400 fertility clinics, 2) more than two-thirds that answered the survey offer PGD, and 3) some clinics that have done it may not have admitted it, the best guess is that at least eight U.S. clinics have done it. Old fear: designer babies. New fear: deformer babies.

Of course Nick Bostrom will push us one step further and ask why the status quo bias? Aren’t we all "deformed" compared to the Uebermensch of the future?

Bob Dylan’s XM broadcasts, as DJ

Too good to be true. I wish to rebel against the Staffan Linder theorem; maybe I’ll have my head frozen after all. Note: the downloads are not quick.

Department of Uh-Oh, a continuing series

After each move Mr. Kramnik immediately heads to the rest room and from it directly to the bathroom. During every game he visited the relaxation room 25 times at the average and the bathroom more than 50 times – the bathroom is the only place without video surveillance…

Should this extremely serious problem remain unsolved by 10.00 o’clock tomorrow (September 29th, 2006), we would seriously reconsider the participation of the World [chess] Champion Veselin Topalov in this match.

Here is the story. Kramnik is leading 3-1; with the exception of his B x f8?? move in game two, his tactical play has been uncannily accurate, and indeed computer-like, at key moments. Or maybe he has learned that new style by playing with computers. Here is my previous post on the topic.

Hire Ben Casnocha

Seth Godin…posed

an idea I call "Real Life University." Seth questioned whether four

years in a place that teaches how to be normal filled with students who

are looking for a degree helps me. He wondered aloud whether two years

on the road traveling in different cultures, and two years reading

books and meeting mentors, would be a better experience.From that point forward my opinion on the matter became clear: I

want to spend four years of my life learning. I don’t want to graduate

from high school and just start more businesses. After all, business is

only kind of interesting. I want to learn. I want to explore."Real Life University" – four years of reading and exploration,

guided by a "board of trustees" of advisors and mentors – became a real

idea I refined and held in my back pocket.

Here is the post, here is Ben’s blog. Here is Ben’s bio. Here is Ben on his GPA and why not every good college will take him. Tomorrow Ben will tell us where he will go in a year’s time. But should he spend four years of his life at a college?

Hire Ben, in a job with real possibilities; if need be give him a "pre doc" to just sit around. If need be, give him part of the year off.

Ben is a living test of whether college education signals the dedication of students to hard work. If Ben does not get or indeed even start his degree, does it mean he is undisciplined? And yes you can see a potential source of worry toward the end of his second paragraph from above.

I have met Ben and he is very nice. I have read Ben’s blog. I spent three minutes with Ben, but I will bet my reputation as a judge of talent that Ben will be a future star of some kind. He is already a star. And someday he will own you.

Hire Ben Casnocha, and test economic theory in the process. Contribute to building a data set for the economics of education.

I’ll give you all an update a year from now.

By the way: I have always thought that the peer effects of college were the

biggest problem with the idea; ideally the smart kids should be sent to

a college full of adult students, if only this were possible.

Nobel Prize predictions

The Economics prize will be announced October 9. Here are speculations from last year. Here are further plausible picks. Gordon Tullock deserves it. I predict Eugene Fama and Richard Thaler as deserving co-winners for their work in empirical finance. Fama will win it for first proving (1972) and then disproving (1992) CAPM, the Capital Asset Pricing Model. Thaler will win it for developing behavioral finance and a better account of how irrationalities manifest themselves in asset markets. Kenneth French, a co-author of Fama’s, might be a third pick. My greatest fear is that they pick Lars Svensson (I believe he is Norwegian, but still that is not a bad name for winning a Swedish prize), and somebody asks me to explain his work.

I believe I have never once predicted this prize correctly. Last year I said Thomas Schelling, the co-winner with Bob Aumann, deserved the prize but might not ever get it. What do you all think?

Addendum: Chris Masse points me to bookie odds on the Peace Prize.