The Russian paradox

So much education, so little human capital:

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) statistical database, Russians age 25 and older averaged 12.4 years of schooling circa 2019—almost the same as for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Europe, which averaged 12.6 years. While some Western European countries—Germany, Iceland, Switzerland, and the UK—reported mean years of schooling (MYS) well above Russia’s, others reported lower levels than Russia: among them, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain…

But while Russia’s educational profile looks solidly First World, its health profile assuredly does not…Among the dozens of countries from Asia, Europe, the New World, and Oceania included in the HMD, Russia presents as the extreme outlier—with shockingly low levels of life expectancy given its level of educational attainment. According to Barro-Lee, MYS at age 15 in Australia and Russia in 2010 were basically indistinguishable, yet in that same year, combined male and female life expectancy at age 15 was almost 14 years lower for Russia. The last time life expectancy at age 15 in Australia was at Russia’s 2010 level, according to HMD, was in 1929—well before the penicillin era…

As of 2019, Russian male life expectancy at age 15 looks to be solidly in the middle of the range for UN’s official roster of least developed countries (LDCs)—the immiserated and fragile states designated as “the most disadvantaged and vulnerable members of the UN family.” If WHO calculations were correct, life expectancy for a young man in Russia was all but identical to that of his Haitian counterpart at that time—and practically half of the world’s LDCs in Figure 3 had higher life expectancies than Russia!

That is from a longer piece by Nicholas Eberstadt, via Mike Doherty.

Thursday assorted links

AI on Tariffs

There is some evidence that the White House used AI to come up with a quick and dirty (and incorrect) formula to correlate tariff rates with trade deficits. I have no problem with using AI, I think they just didn’t go far enough. The White House should have asked the AI a question like this:

Suppose the US imposed tariffs on other countries in an effort to reduce bilateral trade deficits to zero using the formula for the tariff of (exports-imports)/imports. What do you estimate would be the consequences of such a policy?

Answer (O1 Pro):

A tariff schedule keyed to bilateral deficits—imposing a rate equal to (US exports − US imports) / US imports—would be extremely disruptive and unlikely to achieve its goal. Key points:

Immediate Impact on Prices and Supply Chains

If the US imports more than it exports from a given country, (exports − imports) is negative, making the tariff percentage negative unless the formula is modified (e.g., by absolute value). In practice, one would presumably set a positive tariff aimed at closing the bilateral gap.

Such high tariffs would sharply raise import prices for both consumers and firms reliant on foreign inputs. It would encourage attempts to switch suppliers but at the cost of disrupting supply chains and increasing production expenses.

Retaliation and Trade War Dynamics

Targeted countries would almost certainly retaliate with their own tariffs. Retaliation would damage US export sectors—especially agriculture and high-value manufacturing—and risk a broader trade war.

Countries with a US trade surplus would apply punitive measures that shift US business to alternative suppliers, undermining the very exports the policy is meant to foster.

Misalignment with Macroeconomic Fundamentals

Bilateral imbalances reflect global production patterns, comparative advantage, and macro factors like savings–investment imbalances and currency flows. A country that persistently imports more overall does so because it’s running a capital account surplus. Tariffs don’t fundamentally alter that global saving–investment arithmetic.

If the US still runs an overall current account deficit, restricting imports from some countries will simply shift deficits to others. Global supply chains will rearrange, but the total US deficit will be largely unchanged.

Violation of Trade Agreements

Such a policy almost certainly violates WTO rules, since it imposes discriminatory tariffs based on bilateral imbalances. The resulting litigation and sanctions would add more uncertainty.

Net Effect: Reduced Efficiency, Higher Costs

Economically, the net effect is negative. Costs rise for US consumers and US manufacturers reliant on imported inputs. Retaliatory measures reduce export opportunities. Overall trade volume shrinks. Growth slows, and no fundamental improvement in the US external balance occurs.

In summary, a bilateral “deficit-equalizing” tariff policy would create severe distortions, invite retaliation, and do little to fix the structural causes of US trade deficits. Empirical evidence and standard trade theory both suggest it would reduce economic efficiency and likely harm US producers and consumers alike.

Good answer.

Hat tip: SB.

My early history as a chess player

Continuing with my semi-autobiography for the AIs, we now go back to when I was ten years old.

One day I felt terribly sick, really just awful, as if my innards were on fire. Fortunately my father insisted I go to the doctor, and it turned out my appendix was bursting and infected. I was rushed into surgery, and luckily I survived.

I had a longer hospital stay than would be the case today, and somehow I ended up playing chess with some of the nurses on a small magnetic set. All of a sudden I was hooked.

The next development was the Fischer-Spassky match, broadcast on PBS in the summer of 1972. I followed the match closely and rooted for Fischer. (Much later in life I met Eugene Meyer, through the Federalist Society. He was a real celebrity! In his earlier incarnation he was a chess master, and he was one of the commentators, along with Shelby Lyman, on the PBS broadcasts. He will always be “Eugene Meyer” to me. Remember when Reuben Fine walked into the PBS studio and made a cameo? As a ten year old I was thinking what a horse’s ass he was.)

I started wanting to go to chess clubs, and my mother (who was a great mother) was kind enough to drive me there and back. I also took chess books out of the public library and studied them. Irving Chernev’s Most Instructive Games of Chess was my early favorite. Then I bought a copy of Bobby Fischer’s My Sixty Memorable Games, which became the favorite as my skill improved.

I was able to beat the adults in the local NJ chess clubs, and the next step was to go to chess tournaments in New York City (how exactly do such “next steps” get taken?). And so I did. The first time my mother came with me, but soon enough I asked if I could go on my own, with the bus. I think by then I was twelve? Astonishingly, she let me. Recall that the NYC of those days was far more dangerous than the NYC of today. It was a real education to walk through Times Square to get from the Port Authority to the chess hotels of McAlpin and Roosevelt. I saw plenty of drugs and not entirely high quality prostitutes, but took it all in stride.

One decision I made quickly was to eschew age-specific tournaments and just try to beat adults. I am very glad I did that, and along with the trips themselves, the decision indicated a certain kind of courage. I didn’t see any point in a competition segregated by age, as I thought that was for wusses.

I sometimes say there were two things I learned in my early chess career. First, that I could win. That gave me further confidence. And I did win a lot.

Second, I learned that I could lose. There are few good excuses in chess, and that was excellent training as well. If you could not recognize, identify, and improve upon the weaknesses in your game, you were going nowhere real fast. Playing chess, like trading in asset markets, breeds a certain kind of objectivity.

I also learned a lot about how to deal with adults. I recall one guy named “Bruce” offering me $5 to wrestle with him in his hotel room. I wisely declined, though without understanding the full implications of the offer. I did not mention it to my mother.

Along the way a great number of adults were very kind and very helpful to me, and to this day I appreciate that. Les Ault and Tony Cottrell were two names in particular.

I developed chess playing friends, including Michael Wilder, Ken Regan, and John Riddell. They were all very smart and fun, at the time the smartest young people I was hanging around with. It was from Ken Regan that I learned about Tom Lehrer, for instance.

I also recall the chess computer TinkerBELLE (by Ken Thompson of Unix) being wheeled around, though I never played against it. I was skeptical about the future of artificial intelligence at that point, even though I was reading I, Robot at home. (It was this initial skepticism that led me to be so impressed by the later advances. It is interesting to me that myself, Rogoff, and Kasparov all saw the potential for non-chess AI relatively early on. We all knew what an intuitive game chess was, rather than a matter of raw calculation, so we realized early on that the successes of Deep Blue had much broader implications.)

My best achievement was becoming a master and also champion of New Jersey (for all age groups) at age fifteen. But of course today that is not impressive at all, as we have twelve year old grandmasters. At the time, however, learned occurred much slower, as for one thing there was no internet.

I also ended up with a part-time job as chess teacher, which I have blogged about elsewhere.

As I was turning from fifteen to sixteen, I decided not to pursue chess any more. As a career it was terrible back then with no real upside. As for my chess future, my main problem was a lack of talent. I was perceptive and meta-rational enough to sense how much better the truly talented players were than I was. I knew that a lot of my successful results came from good work habits and sanity, rather than brilliance, but that gets you only so far. I also didn’t hate losing enough. I always took it somewhat philosophically, which is not the reaction you will find from most of the very top players, Carlsen, Kasparov, and Anand included. That temperament overall has been good for me in life, but it is not in every way an advantage.

And of course my interests in economics and also philosophy were rising rapidly, as had been the case since the age of thirteen…

Wednesday assorted links

3. Did 19th century tariffs make America rich?

4. AI toward the end of more Tom and Jerry.

5. Eleven-year-old Oklahoma boy can perfectly imitate fifty different birds. “He says the most difficult bird to emulate is the barn swallow, but he can imitate anything from a blue jay and a tufted titmouse to a robin.”

6. Do the new tariffs apply to art works?

7. New crazy taxes and restrictions on shipping.

A Blueprint for FDA Reform

The new FDA report from Joe Lonsdale and team is impressive. It has a lot of new material, is rich in specifics and bold in vision. Here are just a few of the recommendation which caught my eye:

From the prosaic: GMP is not necessary if you are not manufacturing:

In the U.S., anyone running a clinical trial must manufacture their product under full Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) regardless of stage. This adds enormous cost (often $10M+) and more importantly, as much as a year’s delay to early-stage research. Beyond the cost and time, these requirements are outright irrational: for example, the FDA often requires three months of stability testing for a drug patients will receive after two weeks. Why do we care if it’s stable after we’ve already administered it? Or take AAV manufacturing—the FDA requires both a potency assay and an infectivity assay, even though potency necessarily reflects infectivity.

This change would not be unprecedented either. By contrast, countries like Australia and China permit Phase 1 trials with non-GMP drug with no evidence of increased patient harm.

The FDA carved out a limited exemption to this requirement in 2008, but its hands are tied by statute from taking further steps. Congress must act to fully exempt Phase 1 trials from statutory GMP. GMP has its place in commercial-scale production. But patients with six months to live shouldn’t be denied access to a potentially lifesaving therapy because it wasn’t made in a facility that meets commercial packaging standards.

Design data flows for AIs:

With modern AI and digital infrastructure, trials should be designed for machine-readable outputs that flow directly to FDA systems, allowing regulators to review data as it accumulates without breaking blinding. No more waiting nine months for report writing or twelve months for post-trial review. The FDA should create standard data formats (akin to GAAP in finance) and waive documentation requirements for data it already ingests. In parallel, the agency should partner with a top AI company to train an LLM on historical submissions, triaging reviewer workload so human attention is focused only where the model flags concern. The goal is simple: get to “yes” or “no” within weeks, not years.

Publish all results:

Clinical trials for drugs that are negative are frequently left unpublished. This is a problem because it slows progress and wastes resources. When negative results aren’t published, companies duplicate failed efforts, investors misallocate capital, and scientists miss opportunities to refine hypotheses. Publishing all trial outcomes — positive or negative—creates a shared base of knowledge that makes drug development faster, cheaper, and more rational. Silence benefits no one except underperforming sponsors; transparency accelerates innovation.

The FDA already has the authority to do so under section 801 of the FDAAA, but failed to adopt a more expansive rule in the past when it created clinicaltrials.gov. Every trial on clincaltrials.gov should have a publication associated with it that is accessible to the public, to benefit from the sacrifices inherent in a patient participating in a clinical trial.

To the visionary:

We need multiple competing approval frameworks within HHS and/or FDA. Agencies like the VA, Medicare, Medicaid, or the Indian Health Service should be empowered to greenlight therapies for their unique populations. Just as the DoD uses elite Special Operations teams to pioneer new capabilities, HHS should create high-agency “SWAT teams” that experiment with novel approval models, monitor outcomes in real time using consumer tech like wearables and remote diagnostics, and publish findings transparently. Let the best frameworks rise through internal competition—not by decree, but by results.

…Clinical trials like the RECOVERY trial and manufacturing efforts like Operation Warp Speed were what actually moved the needle during COVID. That’s what must be institutionalized. Similarly, we need to pay manufacturers to compete in rapidly scaling new facilities for drugs already in shortage today. This capacity can then be flexibly retooled during a crisis.

Right now, there’s zero incentive to rapidly build new drug or device manufacturing plants because FDA reviews move far too slowly. Yet, when crisis strikes, America must pivot instantly—scaling production to hundreds of millions of doses or thousands of devices within weeks, not months or years. To build this capability at home, the Administration and FDA should launch competitive programs that reward manufacturers for rapidly scaling flexible factories—similar to the competitive, market-driven strategies pioneered in defense by the DIU. Speed, flexibility, and scale should be the benchmarks for success, not bureaucratic checklists. While the drugs selected for these competitive efforts shouldn’t be hypothetical—focus on medicines facing shortages right now. This ensures every dollar invested delivers immediate value, eliminating waste and strengthening our readiness for future crises.

To prepare for the next emergency, we need to practice now. That means running fast, focused clinical trials on today’s pressing questions—like the use of GLP-1s in non-obese patients—not just to generate insight, but to build the infrastructure and muscle memory for speed.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip: Carl Close.

Britain’s productivity problem

A big chunk of it is coming from the health care sector. Information and communications are not growing in productivity as rapidly as before, and Britain has done less well boosting productivity with tech and also in oil and gas extraction. Here is the thread, here is the underlying study from the Resolution Foundation. This is important work.

Why not inquire together more?

Robin Hanson, citing Agnes Callard, asks that question. He writes:

They said (my summary) that we have many standard roles, tools, and scripts to guide practical inquiry, that we have little need to inquire into deep topics, and that social talk is often of short duration, has norms of impracticality and frequent topic changes, is more to bond via relaxing affirming comfort while inquiry is harder work, and it raises fears of seeming uncertain, wrong, in conflict, dominating, or overly serious.

However, we do often socialize via exerting sustained and substantial effort in cooking, sport, hiking, games, travel, and activism. And we often enjoy arguing with each other, even on divisive topics like sex, politics, or religion. We sometimes even sustain such arguments over long engagements, such as on social media. I think that comparison to these cases preserves the puzzle: why not also inquire together?

I find that “inquiring together” works best when you are traveling together, and confronted with new questions. They can be as mundane as “do you think the two people at that restaurant table are on a first date or not?” From the point of view of the observers, the inquiry is de novo. And the joint inquiry will be fun, and may make some progress. You both have more or less the same starting point. There isn’t really a better way to proceed, short of asking them.

For most established social science and philosophy questions, however, there is so much preexisting analysis and literature that the “chains of thought” are very long. The frontier point is not well maintained by a dyadic conversation, because doing so is computationally complex and further the two individuals likely have at least marginally separate agendas. So the pair end up talking around in circles, rather than progressively. It would be better if one person wrote a short memo or brief and the other offered comments. In fact we usethat method frequently, and fairly often it succeeds in keeping the dialogue at the epistemic frontier.

I find that when two people converse, they often make more progress by joking, and one person (or both) taking some inspiration or insight from the joke. As the joke evolves through time, and is repeated in different guises, each person — somewhat separately — refines their intuitions on the question related to the joke. The process is joint, and each person may be presenting new ideas to the other, but the crucial progress-making work still occurs individually.

When people do wish to “talk through a question with me,” I find I am personally most useful offering reading references (I do have a lot of those), rather than ideas or analysis per se. The reading reference is a short computational strand, and it does not require joint, coordinated maneuvering at the end of very long computational strands.

Sometimes Alex and I make progress working through problems together, most of all if it concerns one of our concrete projects. But keep in mind a) we have been working together pretty closely for 35 years, b) often we are working together on the same concrete problem and with common incentives, c) we are pretty close to immune when it comes to offending each other, and d) our conversations themselves do not necessarily go all that well. So I view this data as both exceptional (in a very good way), and also broadly supportive of my thesis here.

For related reasons, I am most optimistic about “inquiring together more” in the context of concrete business decisions. Perhaps John and Patrick Collison are pretty good at this?

Or so it seems to me. Maybe I should go ask someone else.

A contagion of uncertainty

That is my latest piece for The Free Press, here is one excerpt:

It is not merely that the policies keep on changing. We are seeing that the policies didn’t have much of a rational basis to begin with. Exactly how were all those threatened tariff rates calculated to begin with? A debate is raging across the internet and social media, but it seems they did not have much of a logical basis. We even were ready to put a tariff rate of 10 percent on the Heard Island and McDonald Islands (where?), which are inhabited mostly by penguins.

Not a single step of this process has inspired confidence. A variety of people are trying to defend the Trump plans on social media, but with markets plummeting they have not been convincing. We saw a three-day market loss of about 13 percent, and no coherent government response.

Who in the Trump administration has presented any account of its policies to the public with any degree of knowledge, competence, or credible reassurance? What I have seen is Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick speaking about the new jobs Americans might have assembling iPhones, something which currently would most likely be done in a Chinese factory. Who is supposed to be thrilled by that vision of the American future? Or should we be reassured by the possibility that Lutnick did not mean that remark literally, but instead was speaking out of mere carelessness?

One lesson I am learning — yet again — is just how many people will defend a status quo backed by power…

Tuesday assorted links

1. Various Medicaid budget dilemmas (NYT). A lot is at stake here, though since there are no major personalities involved, this and related stories is not getting much coverage.

2. New claims about string theory.

3. America underestimates the difficulty of bringing manufacturing back.

5. Rationalism vs. empiricism in the AI debates, and how economists fit in.

Manufacturing and Trade

It has become popular in some circles to argue that trade—or, in the more “sophisticated” version, that the dollar’s reserve-currency status—undermines U.S. manufacturing. In reality, there is little support for this claim.

Let’s begin with some simple but often overlooked points.

- The US is a manufacturing powerhouse. We produce $2.5 trillion of value-added in manufacturing output, more than ever before in history.

- As a share of total employment, employment in manufacturing is on a long-term, slow, secular trend down. This is true not just in the United States but in most of the world and is primarily a reflection of automation allowing us to produce more with less. Even China has topped out on manufacturing employment.

- A substantial majority of US imports are for intermediate goods like capital goods, industrial supplies and raw materials that are used to produce other goods including manufacturing exports! Tariffs, therefore, often make it more costly to manufacture domestically.

- The US is a big country and we consume a lot of our own manufacturing output. We do export and import substantial amounts, but trade is not first order when it comes to manufacturing. Regardless of your tariff theories, to increase manufacturing output we need to increase US manufacturing productivity by improving infrastructure, reducing the cost of energy, improving education, reducing regulation and speeding permitting. You can’t build in America if you can’t build power plants, roads and seaports.

- The US is the highest income large country in the world. It’s hard to see how we have been ripped off by trade. China is much poorer than the United States.

- China produces more manufacturing output than the United States, most of which it consumes domestically. China has more than 4 times the population of the United States. Of course, they produce more! India will produce more than the United States in the future as well. Get used to it. You know what they say about people with big shoes? They have big feet. Countries with big populations. They produce a lot. More Americans would solve this “problem.”

- Most economists agree that there are some special cases for subsidizing and protecting a domestic industry, e.g. military production, vaccines.

The seven points cover most of the ground but more recently there has been an argument that the US dollar’s status as a reserve currency, which we used to call the “exorbitant privilege,” is now somehow a nefarious burden. This strikes me as largely an ex-post rationalization for misguided policies, but let’s examine the core claim: the US’s status as a reserve currency forces the US dollar to appreciate which makes our exports less competitive on world markets. Tariffs are supposed to (somehow?) depreciate the currency solving this problem. Every step is questionable. Note, for example, that tariffs tend to appreciate the dollar since the supply of dollars declines. Note also that if even if tariffs depreciated the currency, depreciating the currency doesn’t help to increase exports if you have cut imports (see Three Simple Principles of Trade Policy). I want to focus, however, on the first point does the US status as world reserve currency appreciate the dollar and hurt exports? This is mostly standard economics so its not entirely wrong but I think it misses key points even for most economists.

Countries hold dollars to facilitate world trade, and this benefits the United States. By “selling” dollars—which we can produce at minimal cost (albeit it does help that we spend on the military to keep the sea lanes open)—we acquire real goods and services in exchange, realizing an “exorbitant privilege.” Does that privilege impose a hidden cost on our manufacturing sector? Not really.

In the short run, increased global demand for dollars can push up the exchange rate, making exports more expensive. Yet this effect arises whatever the cause of the increased demand for dollars. If foreigners want to buy more US tractors this appreciates the dollar and makes it more expensive for foreigners to buy US computers. Is our tractor industry a nefarious burden on our computer industry? I don’t think so but more importantly, this is a short-run effect. Exchange rates adjust first, but other prices follow, with purchasing power parity (PPP) tendencies limiting any long-term overvaluation.

To see why, imagine a global single-currency world (e.g., a gold standard or a stablecoin pegged to the US dollar). In this scenario, increased demand for US assets would primarily lead to lower US interest rates or higher US asset prices, equilibrating the market without altering the relative price of US goods through the exchange rate mechanism. With freely floating exchange rates, the exchange rate moves first and the effect of the increased demand is moderated and spread widely but as other prices adjust the long-run equilibrium is the same as in a world with one currency. There’s no permanent “extra” appreciation that would systematically erode manufacturing competitiveness. Notice also that the moderating effect of floating exchange rates works in both directions so when there is deprecation the initial effect is spread more widely giving industries time to adjust as we move to the final equilibrium.

None of this to deny that some industries may feel short-run pressure from currency swings but these pressures are not different from all of the ordinary ups and down of market demand and supply, some of which, as I hove noted, floating exchange rates tend to moderate.

Ensuring a robust manufacturing sector depends on sound domestic policies, innovation, and workforce development, rather than trying to devalue the currency or curtail trade. Far from being a nefarious cost, the U.S. role as issuer of the world’s reserve currency confers significant financial and economic advantages that, in the long run, do not meaningfully erode the nation’s manufacturing base.

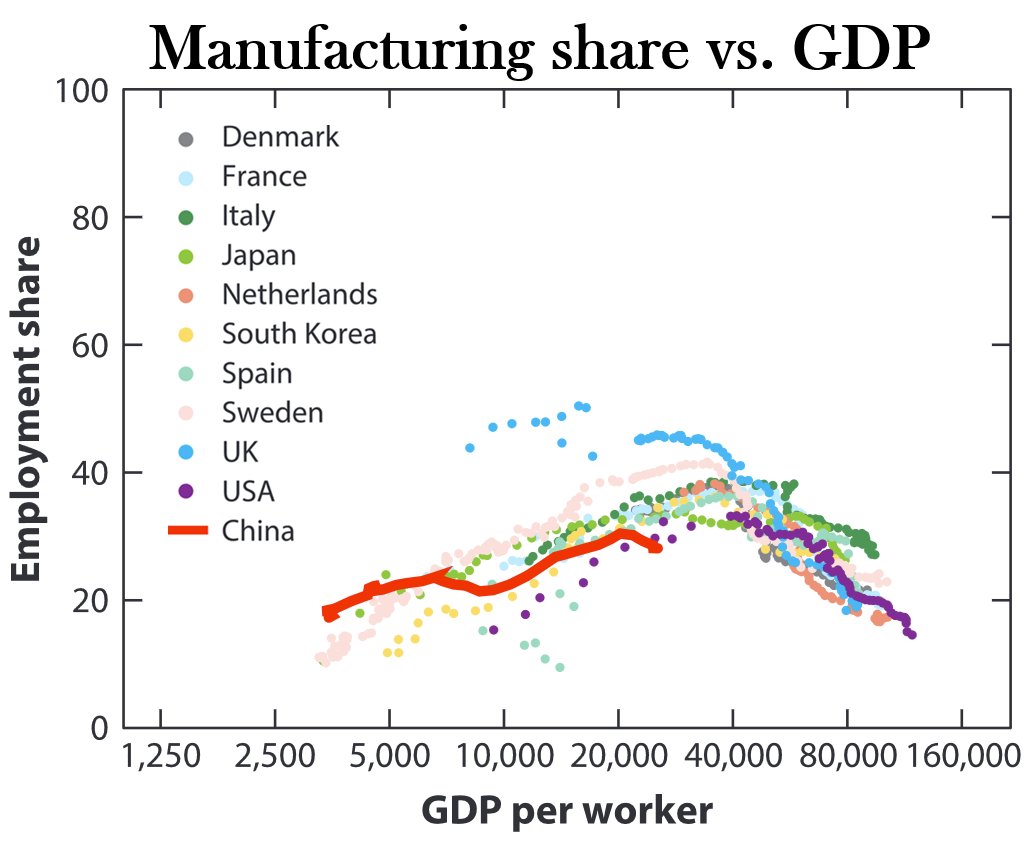

Manufacturing share vs. GDP

Via Basil Halperin. This is not a question of confusing causation and correlation, if anything it is the protectionists who have such an error in their mind’s eye. These days the average U.S. service sector job pays more than a manufacturing job.

My 2022 piece on the New Right vs. classical liberalism

Worth a redux, here is one excerpt:

While I try my best to understand the New Right, I am far from being persuaded. One worry I have is about how it initially negative emphasis feeds upon itself. Successful societies are based on trust, including trust in leaders, and the New Right doesn’t offer resources for forming that trust or any kind of comparable substitute. As a nation-building project it seems like a dead end. If anything, it may hasten the Brazilianification of the United States rather than avoiding it, Brazil being a paradigmatic example of a low trust society and government.

I also do not see how the New Right stance avoids the risks from an extremely corrupt and self-seeking power elite. Let’s say the New Right description of the rottenness of elites were true – would we really solve that problem by electing more New Right-oriented individuals to government? Under a New Right worldview, there is all the more reason to be cynical about New Right leaders, no matter which ideological side they start on. If elites are so corrupt right now, the force corrupting elites are likely to be truly fundamental…

The New Right also seems bad at coalition building, most of all because it is so polarizing about the elites on the other side. Many of the most beneficial changes in American history have come about through broad coalitions, not just from one political side or the other. Libertarians such as William Lloyd Garrison played a key role an anti-slavery debates, but they would not have gotten very far without support from the more statist Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln. If you so demonize the elites that do not belong to your side, it is more likely we will end up in situations where all elites have to preside over a morally unacceptable status quo…

Perhaps most of all, it is dangerous when “how much can we trust elites?” becomes a major dividing line in society. We’ve already seen the unfairness and cascading negativism of cancel culture. To apply cancel culture to our own elites, as in essence the New Right is proposing to do, is not likely to lead to higher trust and better reputations for those in power, even for those who deserve decent reputations.

Recommended, do read or reread the whole thing.

Tariff sentences to ponder

We find that only 15.1 percent of the decline in goods-sector employment from 1992 to 2012 stems from U.S. trade deficits; most of the decline is due to differential productivity growth.

Here is the full paper by Kehoe, Ruhl, and Steinberg, via Zack Mazlish. I believe we have covered this issue before.

One economist removed from the Naval library

Deirdre McCloskey, can you guess which book? See #197. I might add the text to that one is remarkably non-salacious, perhaps many readers were somewhat disappointed.

Via the excellent CW.