Results for “rapid test” 309 found

Early detection of superspreaders by mass group pool testing

Most of epidemiological models applied for COVID-19 do not consider heterogeneity in infectiousness and impact of superspreaders, despite the broad viral loading distributions amongst COVID-19 positive people (1-1 000 000 per mL). Also, mass group testing is not used regardless to existing shortage of tests. I propose new strategy for early detection of superspreaders with reasonable number of RT-PCR tests, which can dramatically mitigate development COVID-19 pandemic and even turn it endemic. Methods I used stochastic social-epidemiological SEIAR model, where S-suspected, E-exposed, I-infectious, A-admitted (confirmed COVID-19 positive, who are admitted to hospital or completely isolated), R-recovered. The model was applied to real COVID-19 dynamics in London, Moscow and New York City. Findings Viral loading data measured by RT-PCR were fitted by broad log-normal distribution, which governed high importance of superspreaders. The proposed full scale model of a metropolis shows that top 10% spreaders (100+ higher viral loading than median infector) transmit 45% of new cases. Rapid isolation of superspreaders leads to 4-8 fold mitigation of pandemic depending on applied quarantine strength and amount of currently infected people. High viral loading allows efficient group matrix pool testing of population focused on detection of the superspreaders requiring remarkably small amount of tests. Interpretation The model and new testing strategy may prevent thousand or millions COVID-19 deaths requiring just about 5000 daily RT-PCR test for big 12 million city such as Moscow.

Speculative, but I believe this is the future of our war against Covid-19.

The paper is by

Supply curves slope upward, Switzerland fact of the day, and how to get more tests done

Under Swiss law, every resident is required to purchase health insurance from one of several non-profit providers. Those on low incomes receive a subsidy for the cost of cover. As early as March 4, the federal health office announced that the cost of the test — CHF 180 ($189) — would be reimbursed for all policyholders.

Here is the article, that reimbursement is about 4x where U.S. levels had been. The semi-good news is that the payments to Abbott are going up:

The U.S. government will nearly double the amount it pays hospitals and medical centers to run Abbott Laboratories’ large-scale coronavirus tests, an incentive to get the facilities to hire more technicians and expand testing that has fallen significantly short of the machines’ potential.

Abbott’s m2000 machines, which can process up to 1 million tests per week, haven’t been fully used because not enough technicians have been hired to run them, according to a person familiar with the matter.

In other words, we have policymakers who do not know that supply curves slope upwards (who ever might have taught them that?).

The same person who sent me that Swiss link also sends along this advice, which I will not further indent:

“As you know, there are 3 main venues for diagnostic tests in the U.S., which are:

1. Centralized labs, dominated by Quest and LabCorp

2. Labs at hospitals and large clinics

3. Point-of-care tests

There is also the CDC, although my understanding is that its testing capacity is very limited. There may be reliability issues with POC tests, because apparently the most accurate test is derived from sticking a cotton swab far down in a patient’s nasal cavity. So I think this leaves centralized labs and hospital labs. Centralized labs perform lots of diagnostic tests in the U.S. and my understanding is this occurs because of their inherent lower costs structures compared to hospital labs. Hospital labs could conduct many diagnostic tests, but they choose not to because of their higher costs.

In this context, my assumption is that the relatively poor CMS reimbursement of COVID-19 tests of around $40 per test, means that only the centralized labs are able to test at volume and not lose money in the process. Even in the case of centralized labs, they may have issues, because I don’t think they are set up to test deadly infection diseases at volume. I’m guessing you read the NY Times article on New Jersey testing yesterday, and that made me aware that patients often sneeze when the cotton swab is inserted in their noses. Thus, it may be difficult to extract samples from suspected COVID-19 patients in a typical lab setting. This can be diligence easily by visiting a Quest or LabCorp facility. Thus, additional cost may be required to set up the infrastructure (e.g., testing tents in the parking lot?) to perform the sample extraction.

Thus, if I were testing czar, which I obviously am not, I would recommend the following steps to substantially ramp up U.S. testing:

1. Perform a rough and rapid diligence process lasting 2 or 3 days to validate the assumptions above and the approach described below, and specifically the $200 reimbursement number (see below). Importantly, estimate the amount of unused COVID-19 testing capacity that currently exists in U.S. hospitals, but is not being used because of a shortage of kits/reagents and because of low reimbursement. This number could be very low, very high or anywhere in between. I suspect it is high to very high, but I’m not sure.

2. Increase CMS reimbursement per COVID-19 tests from about $40 to about $200. Explain to whomever is necessary to convince (CMS?…Congress?…) why this dramatic increase is necessary, i.e., to offset higher costs for reagents, etc. and to fund necessary improvements in testing infrastructure, facilities and personnel. Explain that this increase is necessary so hospital labs to ramp up testing, and not lose money in the process. Explain how $200 is similar to what some other countries are paying (e.g., Switzerland at $189)

3. Make this higher reimbursement temporary, but through June 30, 2020. Hopefully testing expands by then, and whatever parties bring on additional testing by then have recouped their fixed costs.

4. If necessary, justify the math, i.e., $200 per test, multiplied by roughly 1 or 2 million tests per day (roughly the target) x 75 days equals $15 to $30 billion, which is probably a bargain in the circumstances.

5. Work with the centralized labs (e.g., Quest, LabCorp., etc.), hospitals and healthcare clinics and manufactures of testing equipment and reagents (e.g., ThermoFisher, Roche, Abbott, etc.) to hopefully accelerate the testing process.

6. Try to get other payors (e.g., HMOs, PPOs, etc.) to follow CMS lead on reimbursement. This should not be difficult as other payors often follow CMS lead.

Just my $0.02.”

TC again: Here is a Politico article on why testing growth has been slow.

Why are we letting FDA regulations limit our number of coronavirus tests?

Since CDC and FDA haven’t authorized public health or hospital labs to run the [coronavirus] tests, right now #CDC is the only place that can. So, screening has to be rationed. Our ability to detect secondary spread among people not directly tied to China travel is greatly limited.

That is from Scott Gottlieb, former commissioner of the FDA, and also from Scott:

#FDA and #CDC can allow more labs to run the RT-PCR tests starting with public health agencies. Big medical centers can also be authorized to run tests under EUA. For now they’re not permitted to run the tests, even though many labs can do so reliably 9/9 cdc.gov/coronavirus/20

Here is further information about the obstacles facing the rollout of testing. And read here from a Harvard professor of epidemiology, and here. Clicking around and reading I have found this a difficult matter to get to the bottom of. Nonetheless no one disputes that America is not conducting many tests, and is not in a good position to scale up those tests rapidly, and some of those obstacles are regulatory. Why oh why are we messing around with this one?

For the pointer I thank Ada.

Why are Jamaicans the fastest runners in the world?

That is one chapter in Orlando Patterson’s new and excellent The Confounding Island: Jamaica and the Postcolonial Predicament. One thing I like so much about this book is that it tries to answer actual questions you might have about Jamaica (astonishingly, hardly any other books have that aim, whether for Jamaica or for other countries). So what about this question and this puzzle?

Well, in terms of per capita Olympic medals, Jamaica is #1 in the world, doing 3.75 times better by that metric than Russia at #2. This is mostly because of running, not bobsled teams. Yet why is Jamaica as a nation so strong in running?

Patterson suggests it is not genetic predisposition, as neither Nigeria nor Brazil, both homes of large numbers of ethnically comparable individuals, have no real success in running competitions. Nor do Jamaicans, for that matter, do so well in most team sports, including those demanding extreme athleticism. Patterson also cites the work of researcher Yannis Pitsiladism, who collected DNA samples from top runners and did not find the expected correlations.

Patterson instead cites the interaction of a number of social factors behind the excellence of Jamaican running, including:

1. Preexisting role models.

2. The annual Inter-Scholastic Athletic Championship, also known as Champs, which provides a major boost to running excellence.

3. Proximity and cultural ties with the United States, which give athletically talented Jamaicans the chance to access better training and resources.

4. The Jamaican diet and a number of good public health programs, contributing to the strength of potential Jamaican runners (James C. Riley: “Between 1920 and 1950, Jamaicans added life expectancy at one of the most rapid paces attained in any country.”)

5. The low costs of running, and running practice, combined with the “combative individualism” of Jamaican culture, which pulls the most talented Jamaican athletes into individual rather than team sports. (That same culture is supposed to be responsible for dancehall battles and the like as well.)

Whether or not you agree, those are indeed answers. The book also considers “Why Has Jamaica Trailed Barbados on the Path to Sustained Growth?”, “Why is Democratic Jamaica so Violent?”, and a number of questions about poverty. Amazing! Those are indeed the questions I have about Jamaica, among others.

Recommended, you can pre-order here.

The economics of the Protestant Reformation

Here is the abstract of a new paper by Davide Cantoni, Jeremiah Dittmar, and Noam Yuchtman:

The Protestant Reformation, beginning in 1517, was both a shock to the market for religion and a first-order economic shock. We study its impact on the allocation of resources between the religious and secular sectors in Germany, collecting data on the allocation of human and physical capital. While Protestant reformers aimed to elevate the role of religion, we find that the Reformation produced rapid economic secularization. The interaction between religious competition and political economy explains the shift in investments in human and fixed capital away from the religious sector. Large numbers of monasteries were expropriated during the Reformation, particularly in Protestant regions. This transfer of resources shifted the demand for labor between religious and secular sectors: graduates from Protestant universities increasingly entered secular occupations. Consistent with forward-looking behavior, students at Protestant universities shifted from the study of theology toward secular degrees. The appropriation of resources by secular rulers is also reflected in construction: during the Reformation, religious construction declined, particularly in Protestant regions, while secular construction increased,especially for administrative purposes. Reallocation was not driven by pre-existing economic or cultural differences.

For the pointer I thank the excellent Kevin Lewis.

CEO compensation: the latest results

Here’s the latest:

We analyze the long-run trends in executive compensation using a new panel dataset of top executives in large publicly-held firms from 1936 to 2005, collected from corporate reports. This historic perspective reveals several surprising new facts that conflict with inferences based only on data from the recent decades. First, the median real value of compensation was remarkably flat from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, even during times of rapid economic expansion and aggregate firm growth. This finding contrasts sharply with the steep upward trajectory of pay over the past thirty years, which coincided with a period of similarly large increases in aggregate firm size. A second surprising finding is that the sensitivity of an executive’s wealth to firm performance was not inconsequentially small for most of our sample period. Thus, recent years were not the first time when compensation arrangements served to align managerial incentives with those of shareholders. Taken together, the long-run trends in the level and structure of compensation pose a challenge to several common explanations for the widely-debated surge in executive pay of the past several decades, including changes in firms’ size, rent extraction by CEOs, and increases in managerial incentives.

I don’t quite think these results are "surprising" any more, though they would have been three years ago. In my view the analytically noxious "cultural factors" are looming larger in the explanation than we used to think. It’s become increasingly hard to deny top producers what they, in economic terms, are worth.

Means testing for Medicare

Let’s first quote Mark Thoma’s response to my column; it is indirectly a good summary of what I argue:

I believe the political argument that giving everyone a stake in the

program helps to preserve it has more validity than Tyler does, market

failures (some of which hit all income groups) probably play a larger

role in my thinking about government responses to the health care

problem than in his, and I have more confidence than Tyler that a

universal care system has the potential to lower costs.

And now here’s me:

…the idea of cutting some government transfers provokes protest in

some quarters. One major criticism is that programs for the poor alone

will not be well financed because poor people do not have much political

power. Thus, this idea goes, we should try to make transfer programs as

comprehensive as possible, so that every voter has a stake in the

program and will support more spending.But even if this argument

holds true now, it may not be very persuasive when Medicare costs start

to push taxation levels above 50 percent. A more modest program, more

directly aimed at those who need it, might prove more sustainable in

the longer run.Americans have supported the growth of many

programs aimed mainly at the poor. Both Medicaid and the Earned Income

Tax Credit have grown rapidly in size since their inception. The idea

of helping the poor and not having the government take over entire

economic sectors was the original motive behind welfare programs, in

any case.Furthermore, the argument for comprehensive and

universal transfer programs does not meet the ideal of democratic

transparency. If taking care of the poor is the real value in welfare

programs, those programs should be sold as such to the electorate. We

shouldn’€™t give wealthier people benefits just to €œtrick€ them, for

selfish reasons, into voting for greater benefits for everyone, the

poor included.

Here is another point:

Advocates of health care reform tend to be long on ideas for expanding

care and access, but short on practical solutions for cost control. The

argument is often made that single-payer health care systems in Canada

or Europe are cheaper than health care in the United States. But

Medicare is already a single-payer plan, yet its costs are

unsustainable.

Note that I am calling for higher benefits for the poor and lower benefits for higher-income groups. That’s not a popular stance, not even with egalitarians. In fact I view the contemporary left as oddly ill-prepared on the health care issue. Electorally speaking, the issue is fully 100 percent in their court (and they are used to pressing it aggressively), until of course they get their way and have to "meet payroll," so to speak. One attitude is to cite Europe and think that the production possibilities frontier can expand under better management of the U.S. system, even as you cover an extra 40 million people. Another attitude is to face the notion of trade-offs.

Here is the full column. (By the way, I think that HSAs are ineffective as health care reform and that the so-called "right" is floundering on

this issue, just to get in my equal opportunity smack on the blog.)

Addendum: You can make a good argument that (some) public health programs are the best health care investment of all; I just didn’t have enough space in the column to cover that issue.

Second addendum: Greg Mankiw didn’t read so closely. It’s not "an income tax surcharge on sick, old people." It’s a reallocation of benefits toward people of greater need. Is any benefit less than infinity an "income tax surcharge"?

Third addendum: Here is Paul Krugman on the topic.

The greatest basketball team ever?

These Spurs are so quiet, but it should be asked whether they are the best NBA team to have walked on the planet Earth. A few points:

1. Since 1997 they have a winning percentage of over .700, the best in any sport. This includes two previous championship rings, but the current incarnation of the Spurs is believed to be the best.

2. They have absolutely crushed a variety of strong teams from the West, even when Tim Duncan had sore ankles.

3. Their best player, Tim Duncan, should at this point be MVP every year.

4. They are one of the best defensive teams, ever. Bruce Bowen is a first-rate stopper.

5. They are one of the best-coached teams, ever. They have an amazing variety of offensive plays and defensive set-ups. They can play in many different styles, including run and gun fast break, when needed. They are far more than the sum of their parts.

6. They do not appear to have problems with personalities or dissension.

7. They have a very strong bench.

8. You would rather have Manu Ginobili than Kobe Bryant.

9. In any sport where performance is measurable, quality rises over time. Yes there is dilution but overall the best basketball teams are getting better. And the use of foreign players — prominent on the Spurs — is overcoming the dilution problem rapidly.

Can you imagine Bruce Bowen holding MJ to thirty points and Duncan going around Bill Cartwright at will? Could they keep the fast break of the Showtime Lakers in check, while exploiting the relatively weak defense of that team? How would they match up against the 1989-1990 "Bad Boy" Pistons, or the Celtics with Bill Walton?

We should put the low TV ratings aside and start asking these questions.

Deadly Precaution

MSNBC asked me to put together my thoughts on the FDA and sunscreen. I think the piece came out very well. Here are some key grafs:

…In the European Union, sunscreens are regulated as cosmetics, which means greater flexibility in approving active ingredients. In the U.S., sunscreens are regulated as drugs, which means getting new ingredients approved is an expensive and time-consuming process. Because they’re treated as cosmetics, European-made sunscreens can draw on a wider variety of ingredients that protect better and are also less oily, less chalky and last longer. Does the FDA’s lengthier and more demanding approval process mean U.S. sunscreens are safer than their European counterparts? Not at all. In fact, American sunscreens may be less safe.

Sunscreens protect by blocking ultraviolet rays from penetrating the skin. Ultraviolet B (UVB) rays, with their shorter wavelength, primarily affect the outer skin layer and are the main cause of sunburn. In contrast, ultraviolet A (UVA) rays have a longer wavelength, penetrate more deeply into the skin and contribute to wrinkling, aging and the development of melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. In many ways, UVA rays are more dangerous than UVB rays because they are more insidious. UVB rays hit when the sun is bright, and because they burn they come with a natural warning. UVA rays, though, can pass through clouds and cause skin cancer without generating obvious skin damage.

The problem is that American sunscreens work better against UVB rays than against the more dangerous UVA rays. That is, they’re better at preventing sunburn than skin cancer. In fact, many U.S. sunscreens would fail European standards for UVA protection. Precisely because European sunscreens can draw on more ingredients, they can protect better against UVA rays. Thus, instead of being safer, U.S. sunscreens may be riskier.

Most op-eds on the sunscreen issue stop there but I like to put sunscreen delay into a larger context:

Dangerous precaution should be a familiar story. During the Covid pandemic, Europe approved rapid-antigen tests much more quickly than the U.S. did. As a result, the U.S. floundered for months while infected people unknowingly spread disease. By one careful estimate, over 100,000 lives could have been saved had rapid tests been available in the U.S. sooner.

I also discuss cough medicine in the op-ed and, of course, I propose a solution:

If a medical drug or device has been approved by another developed country, a country that the World Health Organization recognizes as a stringent regulatory authority, then it ought to be fast-tracked for approval in the U.S…Americans traveling in Europe do not hesitate to use European sunscreens, rapid tests or cough medicine, because they know the European Medicines Agency is a careful regulator, at least on par with the FDA. But if Americans in Europe don’t hesitate to use European-approved pharmaceuticals, then why are these same pharmaceuticals banned for Americans in America?

Peer approval is working in other regulatory fields. A German driver’s license, for example, is recognized as legitimate — i.e., there’s no need to take another driving test — in most U.S. states and vice versa. And the FDA does recognize some peers. When it comes to food regulation, for example, the FDA recognizes the Canadian Food Inspection Agency as a peer. Peer approval means that food imports from and exports to Canada can be sped through regulatory paperwork, bringing benefits to both Canadians and Americans.

In short, the FDA’s overly cautious approach on sunscreens is a lesson in how precaution can be dangerous. By adopting a peer-approval system, we can prevent deadly delays and provide Americans with better sunscreens, effective rapid tests and superior cold medicines. This approach, supported by both sides of the political aisle, can modernize our regulations and ensure that Americans have timely access to the best health products. It’s time to move forward and turn caution into action for the sake of public health and for less risky time in the sun.

Who was really for “focused protection of the vulnerable”?

Yes I do mean during the Covid-19 epidemic. As a follow-up post to Alex’s, and his follow-up, here are some of the effective measures in protecting the vulnerable, or they would have been more effective, had we done them better:

1. Vaccines, including speedy approval of same.

2. Prepping hospitals in January, once it became clear we should be doing so. That also would have limited lockdowns! And yet we did basically nothing.

3. Speeding up and improving the research process for anti-Covid remedies and protections.

4. First Doses First, when that policy was appropriate, among other policy ideas (NYT).

5. Effective and rapid testing equipment, readily available on the market.

If you were out promoting those ideas, you were acting in favor of protecting the vulnerable. If you were not out promoting those ideas, but instead talked about “protecting the vulnerable” in a highly abstract manner, you were not doing much to protect the vulnerable.

And here are three actions that endangered the vulnerable rather than protecting them:

5. Publishing papers suggesting a very, very low Covid-19 mortality rate, and then sticking with those results in media appearances after said results appeared extremely unlikely to be true.

6. Maintaining vague (or in some cases not so vague) affiliations with anti-vax groups.

7. Not having thought through how “herd immunity” doctrines might be modified by ongoing mutations.

Keep all that in mind the next time you hear the phrase “protecting the vulnerable.”

The Great Barrington Plan: Would Focused Protection Have Worked?

A key part of The Great Barrington Declaration was the idea of focused protection, “allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk.” This was a reasonable idea and consistent with past practices as recommended by epidemiologists. In a new paper, COVID in the Nursing Homes: The US Experience, my co-author Markus Bjoerkheim and I ask whether focused protection could have worked.

Nursing homes were the epicenter of the pandemic. Even though only about 1.3 million people live in nursing homes at a point in time, the death toll in nursing homes accounted for almost 30 per cent of total Covid-19 deaths in the US during 2020. Thus we asked whether focusing protection on the nursing homes was possible. One way of evaluating focused protection is to see whether any type of nursing homes were better than others. In other words, what can we learn from best practices?

The Centers for Medicaire and Medicaid Services (CMS) has a Five-Star Rating system for nursing homes. The rating system is based on comprehensive data from annual health inspections, staff payrolls, and clinical quality measures from quarterly Minimum Data Set assessments. The rating system has been validated against other measures of quality, such as mortality and hospital readmissions. The ratings are pre-pandemic ratings. Thus, the question to ask is whether higher-quality homes had better Covid-19 outcomes? The answer? No.

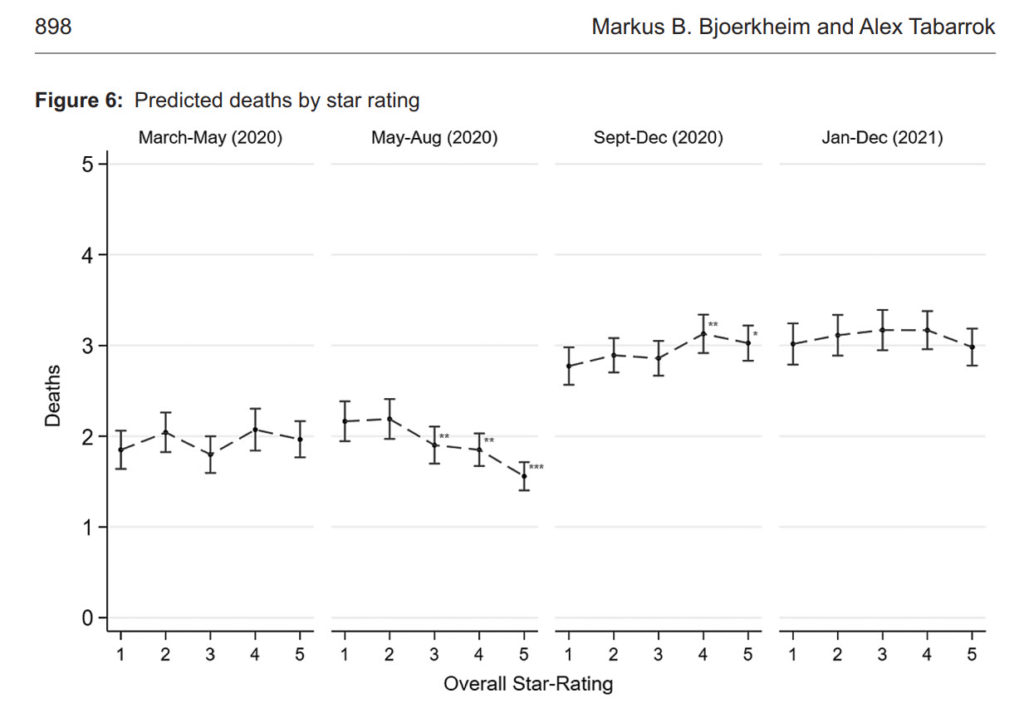

The following figure shows predicted deaths by 5-star rating. There is no systematic relationship between nursing homes rating and COVID deaths. (In the figure, we control for factors outside of a nursing homes control, such as case prevalence in the local community. But even if you don’t control for other factors there is little to no relationship. See the paper for more.) Case prevalence in the community not nursing home quality determined death rates.

More generally, we do some exploratory data analysis to see whether there were any “islands of protection” in the sea of COVID and the answer is basically no. Some facilities did more rapid tests and that was good but surprisingly (to us) the numbers of rapid tests needed to scale nationally and make a substantial difference in nursing home deaths was far out of sample and below realistic levels.

Finally, keep in mind that the United States did focused protection. Visits to nursing homes were stopped and residents and staff were tested to a high degree. What the US did was focused protection and lockdowns and masking and we still we had a tremendous death toll in the nursing homes. Focused protection without community controls would have led to more deaths, both in the nursing homes and in the larger community. Whether that would have been a reasonable tradeoff is another question but there is no evidence that we could have lifted community controls and also better protected the nursing homes. Indeed, as I pointed out at the time, lifting community controls would have made it much more difficult to protect the nursing homes.

The Rise and Decline and Rise Again of Mancur Olson

Mancur Olson’s The Rise and Decline of Nations is one of my favorite books and a classic of public choice. Olson may well have won the Nobel prize had he not died young. He summarized his book in nine implications of which I will present four:

Mancur Olson’s The Rise and Decline of Nations is one of my favorite books and a classic of public choice. Olson may well have won the Nobel prize had he not died young. He summarized his book in nine implications of which I will present four:

2. Stable societies with unchanged boundaries tend to accumulate more collusions and organizations for collective action over time. The longer the country is stable, the more distributional coalitions they’re going to have.

6. Distributional coalitions make decisions more slowly than the individuals and firms of which they are comprised, tend to have crowded agendas and bargaining tables, and more often fix prices than quantities. Since there is so much bargaining, lobbying, and other interactions that need to occur among groups, the process moves more slowly in reaching a conclusion. In collusive groups, prices are easier to fix than quantities because it is easier to monitor whether other industries are selling at a different price, while it may be difficult to monitor the actual quantities they are producing.

7. Distributional coalitions slow down a society’s capacity to adopt new technologies and to reallocate resources in response to changing conditions, and thereby reduce the rate of economic growth. Since it is difficult to make decisions, and since many groups have an interest in the status quo, it will be more difficult to adopt new technologies, create new industries, and generally adapt to changing environments.

9. The accumulation of distributional coalitions increases the complexity of regulation, the role of government, and the complexity of understandings, and changes the direction of social evolution. As the number of distributional coalitions grows, it will make policy-making increasingly difficult, and social evolution will focus more on distributing wealth among groups than on economic efficiency and growth.

Olson’s book has become less well known over the years but you can gauge it’s continued relevance from this excellent thread by Ezra Klein which gets at some of the consequences of the forces Olson explained:

A key failure of liberalism in this era is the inability to build in a way that inspires confidence in more building. Infrastructure comes in overbudget and late, if it comes in at all. There aren’t enough homes, enough rapid tests, even enough good government web sites. I’ve covered a lot of these processes, and it’s important to say: Most decisions along the way make individual sense, even if they lead to collective failure.

If the problem here was idiots and crooks, it’d be easy to solve. Sadly, it’s (usually) not. Take the parklets. There are fire safety concerns. SFMTA is losing revenue. Some pose disability access issues. It’s not crazy to try and take everyone’s concerns into account. But you end up with an outcome everyone kind of hates.

I’ve seen this happen again and again. Every time I look into it, I talk to well-meaning people able to give rational accounts of their decisions.

It usually comes down to risk. If you do X, Y might happen, and even if Y is unlikely, you really don’t want to be blamed for it. But what you see, eventually, is that our mechanisms of governance have become so risk averse that they are now running *tremendous* risks because of the problems they cannot, or will not, solve. And you can say: Who cares? It’s just parklets/HeathCare.gov/rapid tests/high-speed rail/housing/etc.

But it all adds up.

There’s both a political and a substantive problem here.

The political problem is if people keep watching the government fail to build things well, they won’t believe the government can build things well. So they won’t trust it to build. And they won’t even be wrong. The substantive problem, of course, is that we need government to build things, and solve big problems.

If it’s so hard to build parklets, how do you think think that multi-trillion dollar, breakneck investment in energy infrastructure is going to go?

This isn’t a problem that just afflicts liberal governance, of course.All these problems were present federally under Trump and Bush. They are present under Republican governors and mayors. But it’s a bigger problem for liberalism because liberalism has bigger public ambitions, and it requires trust in the government to succeed. I’m going to be working a lot over the next year on the idea of supply-side progressivism, and this is an important part.

ProPublica on FDA Delay

If you have been following MR for the last 18 months (or 18 years!) you won’t find much new in this ProPublica piece on FDA delay in approving rapid tests but, other than being late to the game, it’s a good piece. Two points are worth emphasizing. First, some of the problem has been simple bureaucratic delay and inefficiency.

![]()

In late May, WHPM head of international sales Chris Patterson said, the company got a confusing email from its FDA reviewer asking for information that had in fact already been provided. WHPM responded within two days. Months passed. In September, after a bit more back and forth, the FDA wrote to say it had identified other deficiencies, and wouldn’t review the rest of the application. Even if WHPM fixed the issues, the application would be “deprioritized,” or moved to the back of the line.

“We spent our own million dollars developing this thing, at their encouragement, and then they just treat you like a criminal,” said Patterson. Meanwhile, the WHPM rapid test has been approved in Mexico and the European Union, where the company has received large orders.

An FDA scientist who vetted COVID-19 test applications told ProPublica he became so frustrated by delays that he quit the agency earlier this year. “They’re neither denying the bad ones or approving the good ones,” he said, asking to remain anonymous because his current work requires dealing with the agency.

Recall my review of Joseph Gulfo’s Innovation Breakdown.

Second, the FDA has engaged in regulatory nationalism–refusing to look at trial data from patients in other countries. This is madness when India does it and madness when the US does it.

For example, the biopharmaceutical giant Roche told ProPublica that it submitted a home test in early 2021, but it was rejected by the FDA because the trials had been done partly in Europe. The test had compared favorably with Abbott’s rapid test, and received European Union approval in June. The company plans to resubmit an application by the end of the year.

A smaller company, which didn’t want to be named because it has other contracts with the U.S. government, withdrew its pre-application for a rapid antigen test with integrated smartphone-based reporting because it heard its trial data from India — collected as the delta variant was surging there — wouldn’t be accepted. Doing the trials in the U.S. would have cost millions.

Photo credit: MaxPixel.

The Promising Pathway Act

Operation Warp Speed showed that we can move much faster. FDA delay in approving rapid tests shows that we should move much faster. There is a window of opportunity for reform. The excellent Bart Madden and Siri Terjesen argue for the Promising Pathways Act.

One particularly exciting development is the Promising Pathway Act (PPA), recently introduced in Congress. PPA would reduce bureaucracy via legal changes and provide individuals with efficient early access to potential new drugs.

Under PPA, new drugs will receive provisional approval five to seven years earlier than the status quo via a two-year provisional approval. Drugs that demonstrate patient benefits could be renewed for a maximum of six years, and the FDA could grant full approval at any time based on real-world as opposed to clinical trial data documenting favorable treatments results.

The PPA allows patients, advised by their doctors, to choose early access to promising but not-yet-FDA -approved drugs. Patients and doctors would make informed decisions about using either approved or new medicines that demonstrate safety and initial effectiveness compared to approved drugs.

…Patients and doctors can log into an internet registry database for early access drugs that would contain treatment outcomes, side effects, genetic data, and biomarkers. Scientific researchers, as well as patients, will also benefit from the identification of subgroups of patients who do exceptionally well or fail to respond.

Data from the registry will open knowledge pathways to improve the biopharmaceutical industry’s research outlays to benefit future patients.

With radically lower regulatory costs plus heightened competition as more companies participate, expect substantially lower prescription drug prices for provisional approval drugs.

Here is the text of the PPA.

The TGA is Worse than the FDA, and the Australian Lockdown

I have been highly critical of the FDA but in Australia the FDA is almost a model to be emulated. Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden do not mince words:

At the end of 2020, as vaccines were rolling out en masse in the Northern Hemisphere, the TGA [Therapeutic Goods Administration, AT] flatly refused to issue the emergency authorisations other regulators did. As a result, the TGA didn’t approve the Pfizer vaccine until January 25, more than six weeks after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), itself not exactly the poster child of expeditiousness.

Similarly, the TGA didn’t approve the AstraZeneca vaccine until February 16, almost seven weeks after the UK.

In case you’re wondering “what difference does six weeks make?“, think again. Were our rollout six weeks faster, the current Sydney outbreak would likely never have exploded, saving many lives and livelihoods. In the face of an exponentially spreading virus that has become twice as infectious, six weeks is an eternity. And, indeed, nothing has changed. The TGA approved the Moderna vaccine this week, eight months after the FDA.

It approved looser cold storage requirements for the Pfizer vaccine, which would allow the vaccine to be more widely distributed and reduce wastage, on April 8, six weeks after the FDA. And it approved the Pfizer vaccine for use by 12 to 15-year-olds on July 23, more than 10 weeks after the FDA.

And then there’s the TGA’s staggering decision not to approve in-home rapid tests over reliability concerns despite their widespread approval and use overseas.

Where’s the approval of the mix-and-match vaccine regimen, used to great effect in Canada, where AstraZeneca is combined with Pfizer to expand supply and increase efficacy? Where’s the guidance for those who’ve received two doses of AstraZeneca that they’ll be able to receive a Pfizer booster later?

In the aftermath of the pandemic, when almost all of us should be fully vaccinated,there will be ample opportunity to figure out exactly who is to blame for what.

But the slow, insular, and excessively cautious advice of our medical regulatory complex, which comprehensively failed to grasp the massive consequences of delay and inaction, must be right at the top of that list.

You might be tempted to argued that the TGA can afford to take its time since COVID hasn’t been as bad in Australia as in the United States but that would be to ignore the costs of the Australian lockdown.

Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that

- Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.

- Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Australia has now violated each and every clause of this universal human right and seemingly without much debate or objection. It is deeply troubling to see people prevented from leaving or entering their own country and soldiers in the street making sure people do not travel beyond a perimeter surrounding their homes. The costs of lockdown are very high and thus so is any delay in ending these unprecedented infringements on liberty.