Results for “zero marginal product” 128 found

Dose Stretching Policies Probably *Reduce* Mutation Risk

One objection to dose-stretching policies, such as delaying the second dose or using half-doses, is that this might increase the risk of mutation. While possible, some immunologists and evolution experts are now arguing that dose-stretching will probably reduce mutation risk which is what Tyler and I concluded. Here’s Tyler:

One counter argument is that letting “half-vaccinated” people walk around will induce additional virus mutations. Florian Kramer raises this issue, as do a number of others.

Maybe, but again I wish to see your expected value calculations. And in doing these calculations, keep the following points in mind:

a. It is hard to find vaccines where there is a recommendation of “must give the second dose within 21 days” — are there any?

b. The 21-day (or 28-day) interval between doses was chosen to accelerate the completion of the trial, not because it has magical medical properties.

c. Way back when people were thrilled at the idea of Covid vaccines with possible 60% efficacy, few if any painted that scenario as a nightmare of mutations and otherwise giant monster swarms.

d. You get feedback along the way, including from the UK: “If it turns out that immunity wanes quickly with 1 dose, switch policies!” It is easy enough to apply serological testing to a control group to learn along the way. Yes I know this means egg on the face for public health types and the regulators.

e. Under the status quo, with basically p = 1 we have seen two mutations — the English and the South African — from currently unvaccinated populations. Those mutations are here, and they are likely to overwhelm U.S. health care systems within two months. That not only increases the need for a speedy response, it also indicates the chance of regular mutations from the currently “totally unvaccinated” population is really quite high and the results are really quite dire! If you are so worried about hypothetical mutations from the “half vaccinated” we do need a numerical, expected value calculation comparing it to something we already know has happened and may happen yet again. When doing your comparison, the hurdle you will have to clear here is very high.

(See my Washington Post piece for similar arguments and additional references.).

Now here are evolutionary theorists, immunologists and viral experts Sarah Cobey, Daniel B. Larremore, Yonatan H. Grad, and Marc Lipsitch in an excellent paper that first reviews the case for first doses first and then addresses the escape argument. They make several interrelated arguments that a one-dose strategy will reduce transmission, reduce prevalence, and reduce severity and that all of these effects reduce mutation risk.

The arguments above suggest that, thanks to at least some effect on transmission from one dose, widespread use of a single dose of mRNA vaccines will likely reduce infection prevalence…

The reduced transmission and lower prevalence have several effects that individually and together tend to reduce the probability that variants with a fitness advantage such as immune escape will arise and spread (Wen, Malani, and Cobey 2020). The first is that with fewer infected hosts, there are fewer opportunities for new mutations to arise—reducing available genetic variation on which selection can act. Although substitutions that reduce antibody binding were documented before vaccine rollout and are thus relatively common, adaptive evolution is facilitated by the appearance of mutations and other rearrangements that increase the fitness benefit of other mutations (Gong, Suchard, and Bloom 2013; N. C. Wu et al. 2013; Starr and Thornton 2016). The global population size of SARS-CoV-2 is enormous, but the space of possible mutations is larger, and lowering prevalence helps constrain this exploration. Other benefits arise when a small fraction of hosts drives most transmission and the effective reproductive number is low. Selection operates less effectively under these conditions: beneficial mutations will more often be lost by chance, and variants with beneficial mutations are less certain to rise to high frequencies in the population (Desai, Fisher, and Murray 2007; Patwa and Wahl 2008; Otto and Whitlock 1997; Desai and Fisher 2007; Kimura 1957). More research is clearly needed to understand the precise impact of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 evolution, but multiple lines of evidence suggest that vaccination strategies that reduce prevalence would reduce rather than accelerate the rate of adaptation, including antigenic evolution, and thus incidence over the long term.

In evaluating the potential impact of expanded coverage from dose sparing on the transmission of escape variants, it is necessary to compare the alternative scenario, where fewer individuals are vaccinated (but a larger proportion receive two doses) and more people recover from natural infection. Immunity developing during the course of natural infection, and the immune response that inhibits repeat infection, also impose selection pressure. Although natural infection involves immune responses to a broader set of antibody and T cell targets compared to vaccination, antibodies to the spike protein are likely a major component of protection after either kind of exposure (Addetia et al. 2020; Zost et al. 2020; Steffen et al. 2020), and genetic variants that escape polyclonal sera after natural infection have already been identified (Weisblum et al. 2020; Andreano et al. 2020). Studies comparing the effectiveness of past infection and vaccination on protection and transmission are ongoing. If protective immunity, and specifically protection against transmission, from natural infection is weaker than that from one dose of vaccination, the rate of spread of escape variants in individuals with infection-induced immunity could be higher than in those with vaccine-induced immunity. In this case, an additional advantage of increasing coverage through dose sparing might be a reduction in the selective pressure from infection-induced immunity.

…In the simplest terms, the concern that dose-sparing strategies will enhance the spread of immune escape mutants postulates that individuals with a single dose of vaccine are those with the intermediate, “just right” level of immunity, more likely to evolve escape variants than those with zero or two doses (Bieniasz 2021; Saad-Roy et al. 2021)….There is no particular reason to believe this is the case. Strong immune responses arising from past infection or vaccination will clearly inhibit viral replication, preventing infection and thus within-host adaptation…. Past work on influenza has found no evidence of selection for escape variants during infection in vaccinated hosts (Debbink et al. 2017). Instead, evidence suggests that it is immunocompromised hosts with prolonged influenza infections and high viral loads whose viral populations show high diversity and potentially adaptation (Xue et al. 2017, 2018), a phenomenon also seen with SARS-CoV-2 (Choi et al. 2020; Kemp et al. 2020; Ko et al. 2021). It seems likely, given its impact on disease, that vaccination could shorten such infections, and there is limited evidence already that vaccination reduces the amount of virus present in those who do become infected post-vaccination (Levine-Tiefenbrun et al. 2021).

I also very much agree with these more general points:

The pandemic forces difficult choices under scientific uncertainty. There is a risk that appeals to improve the scientific basis of decision-making will inadvertently equate the absence of precise information about a particular scenario with complete ignorance, and thereby dismiss decades of accumulated and relevant scientific knowledge. Concerns about vaccine-induced evolution are often associated with worry about departing from the precise dosing intervals used in clinical trials. Although other intervals were investigated in earlier immunogenicity studies, for mRNA vaccines, these intervals were partly chosen for speed and have not been completely optimized. They are not the only information on immune responses. Indeed, arguments that vaccine efficacy below 95% would be unacceptable under dose sparing of mRNA vaccines imply that campaigns with the other vaccines estimated to have a lower efficacy pose similar problems. Yet few would advocate these vaccines should be withheld in the thick of a pandemic, or roll outs slowed to increase the number of doses that can be given to a smaller group of people. We urge careful consideration of scientific evidence to minimize lives lost.

Fallacies about constraints

I am reading many people claim something like “production and distribution of the vaccine is the constraint, not FDA approval.”

There are multiple mistakes in such a view, and here I wish to focus on the logic of constraints rather than debate the FDA issue.

First, there are vaccines available right now, and it helps some people (and their contacts) to have those distributed sooner rather than later.

Second, easing the FDA constraint encourages the suppliers and distributors to hurry to a greater degree. Just imagine if the FDA were to take a few months longer to approve. The more general point is that citing “x is right now the main constraint right now” does not mean “the elasticity of x is zero.”

“Sure” wrote in the comments:

On the economics side, I am not convinced that production has ramped up as full and as fast as possible. After all there is some risk premium for expanding plants, running constant shifts, etc. and the danger of delayed approval, particularly if you are in some (mostly negligible) way to the other vaccines may not warrant the investment.

After all, approvals appear to move stocks. Do we really think the market is that dumb? If approval has an impact on market value, why exactly would it not also have an impact on the cost of borrowing, expanding, etc.? Surely somebody believes that approval will result in something different will happen than was happening the day before.

Third, “FDA vaccine approval” is a complementary good for the final vaccine service, strongly complementary in fact. If the other complementary infrastructure goods have price/quality combinations that are “too disadvantageous,” the theory of the second best implies that approval processes should be speedier and more lax than you otherwise might have thought. This is just the converse of the classic result that multiple medieval princes imposing multiple tolls on a river create negative externalities for both river users and each other. Lower those tolls wherever you can.

Fourth, let’s say there were three constraints, each absolutely binding at the current margin. Speeding FDA approval, taken alone, would have absolutely no effect. We then ought to be obsessed with identifying and remedying the other two constraints (along with approval)!

But we are not. Instead we keep on citing those (supposed) constraints in defeatist fashion. This absence of obsession with easing constraints is in fact one of the biggest reasons for thinking we can do better. We need to throw more money and talent at these problems, and we are not working hard enough on how to do that. We are just citing the constraints back and forth to each other and pleading helplessness.

As a final note, I recall that my recently deceased colleague Walter E. Williams was especially good on these issues. I recall him once saying he wanted to hire a helicopter to drop a cow into the campus central quad, just to show people that supply has positive elasticity. “I’m going to call them up and say “Williams wants a cow!””

Moo.

Platform Economics in Modern Principles

Why is Facebook free? Why are credit cards less than free? Why do singles bars sometimes have women drink free nights but never men drink free nights? All of these questions are in the domain of platform economics. Platform economics is new. Tirole and Rochet practically invented the field with a seminal paper in 2003–and that paper was one of the reasons Tirole won the Nobel prize in 2014. Despite being new, platform economics deals with goods which are fundamental to the modern economy. Thus, Tyler and I thought that it was incumbent upon us to teach some of the intuition behind platform economics in Modern Principles of Economics. But students have enough new material to learn, so we set ourselves a challenge–explain the intuition of platform economics using principles that the students already know. Surprisingly, platform economics can be taught with just two principles: externalities and elasticities.

In our chapter on externalities we offer the students a puzzle. Why do some firms offer their workers free flu shots? The answer, as memorably illustrated in this video, is that the firm “internalizes the externality.” When one worker gets a flu shot, other workers at the firm are less likely to get sick. In principle, the workers could subsidize one another to achieve the efficient outcome but transactions costs makes that solution impractical (the Coase theorem). The firm, however, is already involved in transactions with all the workers and, as a result, it can subsidize flu shots and reap the benefits of workers taking fewer sick days. How much the firm should subsidize flu shots depends on the elasticity of flu shots with respect to the price and on the elasticity of sick days with respect to vaccinated workers.

In our chapter on externalities we offer the students a puzzle. Why do some firms offer their workers free flu shots? The answer, as memorably illustrated in this video, is that the firm “internalizes the externality.” When one worker gets a flu shot, other workers at the firm are less likely to get sick. In principle, the workers could subsidize one another to achieve the efficient outcome but transactions costs makes that solution impractical (the Coase theorem). The firm, however, is already involved in transactions with all the workers and, as a result, it can subsidize flu shots and reap the benefits of workers taking fewer sick days. How much the firm should subsidize flu shots depends on the elasticity of flu shots with respect to the price and on the elasticity of sick days with respect to vaccinated workers.

Now what does this have to do with Facebook? Well think about seeing ads as a bit like getting a flu shot–seeing ads has a benefit to you but it’s also a bit of a pain so if you had a choice you might not watch that many ads. But advertisers want you to see ads–in other words, Facebook users who see ads create a positive externality for advertisers. The platform firm, Facebook, internalizes this externality and that means subsidizing ad-seeing by selling Facebook at a zero price to readers and instead charging advertisers. As we put it in Modern Principles:

Imagine that Facebook begins with a positive price for both readers and advertisers (PR>0 and PA>0). Readers, however, are likely to be sensitive to the price so a small decrease in price will cause a large increase in readers (very elastic demand). Thus, imagine that Facebook lowers the price to readers and thus increases the number of readers. With more readers, Facebook can charge its advertisers more, so PA increases. Indeed, if the demand for advertisers increases enough, it can even pay Facebook to lower the price to readers to zero! Thus, the key to Facebook’s decision is how many more readers it will get when it lowers the price (the reader elasticity), how much those readers are worth to advertisers (the externality of readers to advertisers) and how high can it increase the price to advertisers (the advertiser elasticity).

More in the textbook!

A Calculation of the Social Returns to Innovation

Benjamin Jones and Larry Summers have an excellent new paper calculating the returns to social innovation.

This paper estimates the social returns to investments in innovation. The disparate spillovers associated with innovation, including imitation, business stealing, and intertemporal spillovers, have made calculations of the social returns difficult. Here we provide an economy-wide calculation that nets out the many spillover margins. We further assess the role of capital investment, diffusion delays, learning-by-doing, productivity mismeasurement, health outcomes, and international spillovers in assessing the average social returns. Overall, our estimates suggest that the social returns are very large. Even under conservative assumptions, innovation efforts produce social benefits that are many multiples of the investment costs.

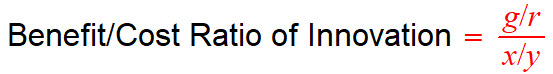

What was interesting to me is that their methods of calculation are obvious, almost trivial. It can take very clever people to see the obvious. Essentially what they do is take the Solow model seriously. The Solow model says that in equilibrium growth in output per worker comes from productivity growth. Suppose then that productivity growth comes entirely from innovation investment then this leads to a simple expression:

Where g is the growth rate of output per worker (say 1.8% per year), r is the discount rate (say 5%), and x/y is the ratio of innovation investment, x, to GDP, y, (say 2.7%). Plugging the associated numbers in we get a benefit to cost ratio of (.018/.05)/.027=13.3.

Where g is the growth rate of output per worker (say 1.8% per year), r is the discount rate (say 5%), and x/y is the ratio of innovation investment, x, to GDP, y, (say 2.7%). Plugging the associated numbers in we get a benefit to cost ratio of (.018/.05)/.027=13.3.

To see where the expression comes from suppose we are investing zero in innovation and thus not growing at all. Now imagine we invest in innovation for one year. That one year investment improves economy wide productivity by g% forever (e.g. we learn to rotate our crops). The value of that increase, in proportion to the economy, is thus g/r and the cost is x/y.

Jones and Summers then modify this simply relation to take into account other factors, some of which you have undoubtedly already thought of. Suppose, for example, that innovation must be embodied in capital, a new design for a nuclear power plant, for example, can’t be applied to old nuclear power plants but most be embodied in a new plant which also requires a lot of investment in cement and electronics. Net domestic investment is about 4% of GDP so if all of this is necessary to take advantage of innovation investment (2.7% of gdp), we should increase “required” to 6.7% of GDP which is equivalent to multiplying the above calculation by 0.4 (2/7/6.7). Doing so reduces the benefit to cost ratio to 5.3 which means we still get a very large internal rate of return of 27% per year.

Other factors raise the benefit to cost ratio. Health innovations, for example, don’t necessarily show up in GDP but are extremely valuable. Taking health innovation cost out of x means every other R&D investment must be having a bigger effect on GDP and so raises the ratio. Alternatively, including health innovations in benefits, a tricky calculation since longer life expectancy is valuable in itself and raises the value of GDP, increases the ratio even more. (See also Why are the Prices So Damn High? on this point). International spillovers also increase the value of US innovation spending.

Bottom line is, as Jones and Summers argue, “analyzing the average returns from a wide variety of perspectives suggests that the social returns [to innovation spending] are remarkably high.”

*The Deficit Myth* and Modern Monetary Theory

That is the new book by Stephanie Kelton and the subtitle is Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. Here are a few observations:

1. Much of it is quite unobjectionable and well-known, dating back to the Bullionist debates or earlier yet. Yet regularly it flies off the handle and makes unsupported macroeconomic assertions.

2. Like many of the Austrians, Kelton likes to insist on special terms, such as the government spending “coming first.” You don’t have to say this is wrong, just keep your eye on the ball and don’t let it distract you.

3. “MMT has emphasized that rising interest income can serve as a potential form of fiscal stimulus.” You don’t have to believe in a naive form of Say’s Law, but discussions of demand should start with the notion of production. Then…never reason from an interest rate change! Overall, I sense Kelton has one core model of the macroeconomy, with a whole host of variables held fixed (“well…higher interest rates means printing up more money to pay for them and thus greater stimulus…”), and then applies that model to a whole series of quite general problems and questions.

4. She thinks “demand” simply puts resources to work, and in this sense the book is a nice reductio ad absurdum of the economics one increasingly sees from mainstream writers on Twitter. p.s.: The economy doesn’t have a “speed limit.” And it shouldn’t be modeled using analogies with buckets.

5. We are told that the U.S. “…can’t lose control of its interest rate”, but real and nominal interest rates are not distinguished with care in these discussions. The Fed’s ability to control real rates is fairly limited, though not zero, and those are empirical truths never countered or even confronted in this book.

6. The absence of a nominal budget constraint is confused repeatedly with the absence of a real budget constraint. That is one of the major errors in this book.

7. It still would be very useful if the MMT people would take a mainstream macro model and spell out which assumptions they wish to make different, and then solve for the properties of the new model. There is a reason why they won’t do that.

8. I don’t care what the author says or how canonical she is as a source, a federal jobs guarantee is not part of MMT.

9. Just because the economy is not at absolute full unemployment, it does not mean that free resources are on the table for the taking. Again, in this regard Kelton is a useful reductio on a lot of “Twitter macro.”

10. I am plenty well read in the “money cranks” of earlier times, including Soddy, Foster, Catchings, Kitson, Proudhon, Tucker, and many more. They got a lot of things right, but they also failed to produce coherent macro theories. I would strongly recommend that Kelton undertake a close study of their failings.

11. For all the criticisms of the quantity theory, I would like to know how the MMT people explain the Fed coming pretty close to its inflation rate target for many years in a row, under highly varying conditions, fiscal conditions too.

12. The real grain of truth here is that if monetary policy is otherwise too deflationary, monetizing parts or all of the budget deficit is not only possible, it is desirable. Absolutely, but don’t then let somebody talk loops around you.

You can order the book here.

Social distancing should never be too restrictive

That is the topic of a new paper by Farboodi, Jarosch, and Shimer, published version in here. They favor ” Immediate social distancing that ends only slowly but is not overly restrictive.” Furthermore, they test the model against data from Safegraph and also from Sweden and find that their recommendations do not depend very much on parameter values.

Here is an excerpt from the paper:

…social distancing is never too restrictive. At any point in time, the effective reproduction number for a disease is the expected number of people that an infected person infects. In contrast to the basic reproduction number, it accounts for the current level of social activity and the fraction of people who are susceptible. Importantly, optimal policy keeps the effective reproduction number above the fraction of people who are susceptible,although for a long time only mildly so. That is, social activity is such that, if almost everyone were susceptible to the disease, the disease would grow over time. That means that optimal social activity lets infections grow until the susceptible population is sufficiently small that the number of infected people starts to shrink. As the stock of infected individuals falls,the optimal ratio of the effective reproduction number to the fraction of susceptible people grows until it eventually converges to the basic reproduction number.

To understand why social distancing is never too restrictive, first observe that social activity optimally returns to its pre-pandemic level in the long run, even if a cure is never found. To understand why, suppose to the contrary that social distancing is permanently imposed, suppressing social activity below the first-best (disease-free world) level. That means that a small increase in social activity has a first-order impact on welfare. Of course, there is a cost to increasing social activity: it will lead to an increase in infections. However,since the number of infected people must converge to zero in the long run, by waiting long enough to increase social activity, the number of additional infections can be made arbitrarily small while the benefit from a marginal increase in social activity remains positive.

Recommended, one recurring theme is that people distance a lot of their own accord. That means voluntary self-policing brings many of the benefits of a lockdown. Another lesson is that we should be liberalizing at the margin.

If I have a worry, however, it has to do with the Lucas critique. People make take preliminary warnings very seriously, when they see those warnings are part of a path toward greater strictness. When the same verbal or written message is part of a path toward greater liberalization however…perhaps the momentum and perceived end point really matters?

For the pointer I thank John Alcorn.

The Consequences of Treating Electricity as a Right

In poor countries the price of electricity is low, so low that “utilities lose money on every unit of electricity that they sell.” As a result, rationing and shortages are common. Writing in the JEP, Burgess, Greenstone, Ryan and Sudarshan argue that “these shortfalls arise as a consequence of treating electricity as a right, rather than as a private good.”

In poor countries the price of electricity is low, so low that “utilities lose money on every unit of electricity that they sell.” As a result, rationing and shortages are common. Writing in the JEP, Burgess, Greenstone, Ryan and Sudarshan argue that “these shortfalls arise as a consequence of treating electricity as a right, rather than as a private good.”

How can treating electricity as a right undermine the aim of universal access to reliable electricity? We argue that there are four steps. In step 1, because electricity is seen as a right, subsidies, theft, and nonpayment are widely tolerated. Bills that do not cover costs, unpaid bills, and illegal grid connections become an accepted part of the system. In step 2, electricity utilities—also known as distribution companies—lose money with each unit of electricity sold and in total lose large sums of money. Though governments provide support, at some point, budget constraints start to bind. In step 3, distribution companies have no option but to ration supply by limiting access and restricting hours of supply. In effect, distribution companies try to sell less of their product. In step 4, power supply is no longer governed by market forces. The link between payment and supply has been severed: those evading payment receive the same quality of supply as those who pay in full. The delinking of payment and supply reinforces the view described in step 1 that electricity is a right [and leads to] a low-quality, low-payment equilibrium.

The Burgess et al. analysis coheres with my observations in India where “wire anarchy” is common (see picture). It’s obvious that electricity is being stolen but no one does anything about it because it’s considered a right and a government that did do something about it would be voted out of power.

The stolen electricity means that the utility can’t cover its costs. Government subsidies are rarely enough to satisfy the demand at a zero or low price and so the utility rations.

The consequences for electricity consumers, both rich and poor, are severe. There is only one electricity grid, and it becomes impossible to offer a higher quantity or quality of supply to those consumers who are willing and sometimes even desperate to pay for it.

Moreover,the issue is not poverty per se.

…the vast majority of customers in Bihar expect no penalty from paying a bill late, illegally hooking into the grid, wiring around a meter, or even bribing electricity officials to avoid payment. These attitudes are in stark contrast to how the same consumers view payment for private goods like cellphones. It is debatable whether cellphones are more important than electricity, but in Bihar we find that the poor spend three times more on cellphones than they do on elec-tricity (1.7 versus 0.6 percent of total expenditure).

Burgess et al. frame the issue as “treating electricity as right,” but one can can also understand this equilibrium as arising from low state capacity and corruption, in particular corruption with theft. In corruption with theft the buyer pays say a meter reader to look the other way as they tap into the line and they get a lower price for electricity net of the bribe. Corruption with theft is a strong equilibrium because buyers who do not steal have higher costs and thus are driven out of the market. In addition, corruption with theft unites the buyer and the corrupt meter reader in secrecy, since both are gaining from the transaction. As Shleifer and Vishny note:

This result suggests that the first step to reduce corruption should be to create an accounting system that prevents theft from the government.

Burgess et al. agree noting, “reforms might seek to reduce theft of electricity and nonpayment of bills” and they point to programs in India and Pakistan that allow utilities to cut off entire neighborhoods when bills aren’t paid. Needless to say, such hardball tactics require some level of trust that when the bills are paid the electricity will be provided and at higher levels of quality–this may be easier to do when there are other sources of authority such as trusted religious leaders.

In essence the problem is that the government is too beholden to electricity consumers. If the government could commit to a regime of no or few subsidies, firms would supply electricity and prices would be low and quality high. But if firms do invest in the necessary electricity infrastructure the government will break its promise and exploit the firms for temporary electoral advantage. As a result, the consumers don’t get much electricity. The government faces a time consistency problem. Independent courts would help to bind the government but those often aren’t available in developing countries. Another possibility is a conservative electricity czar who, like a conservativer central banker, doesn’t share the preferences of the government or the voters. Again that requires some independence.

In short, to ensure that everyone has access to high quality electricity the government must credibly commit that electricity is not a right.

How robust are supply chains?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Consider the supply chain of the Apple iPhone, which stretches across dozens of companies and several continents. Such complex cross-national supply chains generate relatively high profits, giving them a kind of immunity to small disruptions. If there is an unexpected tax, tariff or exchange movement, the supply chain can generally swallow the costs and move on. Profits will be lower within the supply chain, but production will continue, as it is too lucrative to simply shut everything down.

Do not be deceived, however: Supply chains are not indestructible. If the new costs or risks are high enough, the entire structure will be dismantled. By their nature, supply chains do not fall apart slowly, because each part of the chain relies upon other parts to add its value. It does not help much to have the circuit components of the iPhone lined up, for instance, if you cannot also produce the glass screens. In this way, these supply chains are less robust under extreme conditions.

Global supply chains have yet to come apart mostly because trade and prosperity generally have been rising. But now, for the first time since World War II, the global economy faces the possibility of a true decoupling of many trade connections.

It is not sufficiently well understood how rapid that process could be. A complex international supply chain is fragile precisely for the same reasons it is valuable — namely, it is hard to construct and maintain because it involves so many interdependencies.

The nature of the cross-national supply chain makes it especially vulnerable to shocks coming from the coronavirus. These supply chains do not adapt so well to complete cutoffs in materials or labor, as may happen if Chinese coronavirus casualties continue and workplaces find it hard to operate effectively.

Imagine that closed Chinese factories cannot produce the components of many American medicines. It is not a question of the supply chain simply losing some profits; rather, some critical pieces of the production process are missing. The medicines won’t work without these inputs. The U.S. medical establishment might try to source those components elsewhere, but it isn’t easy for other suppliers to produce enough of them at sufficient scale and quality.

U.S. medical producers might try to bid more for the Chinese medicine components, but if the workers are prohibited from even showing up at the factory, no feasible market clearing price can make this arrangement work. Production just won’t be possible. Fashionable practices of near-zero inventories can make these shortages appear all the more rapidly. About 80% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients in U.S. medicines rely on Chinese or Indian components, so this does represent a very real public health risk for the U.S., even if the coronavirus itself does not.

You will note that when it comes to ex ante planning, companies do not in general internalize the costs of a supply chain cut-off to their customers, since consumer surplus for the infra-marginal buyers exceeds market price. Supply chain are thus too fragile relative to an optimum, though that matters only under very limited circumstances, as we may be seeing right now.

Libra as a medium of exchange

I’ve already outlined the case for how Libra might be able to significantly lower the 7-8% costs and commissions currently charged for making remittances. That would make Libra a widely used means of payment. I am less optimistic, however, about Libra being widely used as a medium of exchange.

Let’s say the core rate of inflation in a country is eight percent, which is about the current rate of price inflation in Myanmar. It is still not the case that an unbanked farmer holds currency for the entire year (he is more likely to buy land or animals as a means of large-scale saving). I am not sure what monetary velocity is for this group of people (readers?), but say currency turns over four times a year on average. That is in essence a two percent tax on currency holdings, not an eight percent tax. I don’t think that individuals will switch monies for such a small gain, noting that decreasing their demand for money (i.e., increasing currency velocity) is another possible response.

If an unbanked farmer is in debt, I would think the velocity of currency would be well over 4x a year (consider monthly microcredit borrowings and repayments), although certainly some MR readers can enlighten us here.

A few decades ago, when inflation was much more common, it was generally believed that people were not very interested in switching monies until inflation rates hit about forty percent. I am not sure if that same number would hold today, but of course that is pretty high. Furthermore, the countries with the highest inflation rates, such as Venezuela, can be impossible to do business in.

Don’t forget that Libras are specified as paying zero nominal interest throughout.

You might think that Libras have some advantages over current e-monies and smart phone banking systems. It is hard to make that judgment for a product which does not exist yet, but it is unlikely those advantages will run close to the range of seven to eight percent.

For those reasons I am more optimistic about Libra as a means of payment — most of all for remittances — than as a general medium of exchange.

Libra and remittances

Dante Disparte, as interviewed by Ben Thompson ($$, but you should subscribe to Ben):

One example is the use case of international money transfers or remittances. Globally, the remittance cash flow is projected to be about $715 billion in 2019, and on average…you are seeing between seven and ten percent of transfer costs, and in some instances much higher than that in the teens. For a product and an outcome from the sender and receiver point of view, that is not only very slow, it often takes a few days to clear on the receiving end, it is [extremely expensive]. There are direct payment rails that are just technology powered that do a lot in terms of advancing efficiency, but pre-blockchain it would have been very, very hard to conceive of a network of international payments that could do that at near zero cost instantaneously while at the same time not sacrificing the type of ledgering and transaction information that would enable the world to begin to do that securely. So that would be one amazing use case that could put billions and billions of dollars back into the market by eliminating as many of these fees as possible, while at the same time putting billions of dollars into the hands of people around the world in real time.

Here is my current understanding of Libra/Calibra, at least within this particular context, noting again that my understanding may be wrong or incomplete. These transfers would not go through the current banking system as we know it, but rather through a blockchain with say 100 or so (quite legitimate) participants enforcing some kind of “proof of stake” standard. Some form of “proof of stake-equivalent of mining fees” would have to be paid, either explicitly or implicitly, and those arguably could be much lower than current remittance costs, noting that the actual operation of proof of stake in this setting remains to me murky. Still, it would largely avoid the current mining fees associated with Bitcoin. On net, one is trading in the current regulatory and clearing and Western Union branch costs for these future proof of stake costs. Do you think the Libra Association can run a proof of stake system for less say than $100 billion?

“But don’t you have to convert your Libras back into mainstream fiat currencies?” Well, maybe you might, but that is simply the cost of showing up at the relevant financial institutions and claiming redemption. Those costs also could be much lower than the current fees associated with remittances. What is sent through the blockchain network simply can be Libras, as I understand it, with varying assumptions on how much people will hold Libras rather than converting them.

To use a historical analogy, think of this as substituting “the transfer of paper claims to gold” for “claims to gold,” but in a one hundred percent reserves setting. It can be (and indeed was) much cheaper to send around the paper than the gold, and yet the paper still was a claim to the gold. The Libra is a kind of parallel, redeemable currency, legally not within standard banking systems, but still redeemable in terms of mainstream fiat currencies which are within standard banking systems. “Create a synthetic claim which can be traded more cheaply” would be my version of the ten-word slogan.

Another slightly wordier slogan might be: “let’s actually separate the means of payment from the medium of exchange by creating a new synthetic asset, because those two things actually should not be the exact same asset.”

Of course it still remains to be seen in which countries regulators will allow this to happen. How persuasive is the promise of one hundred percent reserves? I don’t mean to speak for Libra/Calibra here, but I believe they are suggesting (or implying?) that the proof of stake system for making and validating transfers could in essence enforce relevant regulations against money laundering, illegal transfers, and the like.

It is a quite separate (but possible) claim to believe that libras could serve as an effective medium of exchange at a retail level, and perhaps I will cover that in a separate post. That would mean that both the medium of exchange and means of payment should be new and different assets, a much stronger claim.

Here are my earlier questions about Libra, with responses.

Gross Domestic Error

Pierre Lemieux at EconLib catches a surprising error from The Economist which wrote this week:

There was some head-scratching this week, as data showed Japan’s economy growing by 2.1% in the first quarter at an annualised rate, defying expectations of a slight contraction. Most of the growth was explained by a huge drop in imports. Because they fell at a faster rate than exports, gdp rose.

Nope. Imports do not influence Gross Domestic Product, at least not in the mechanical way suggested by The Economist. Here’s how Tyler and I explain it in Modern Principles:

It’s important to remember the Domestic in Gross Domestic Product. When we add C+I+G we are adding up all national spending but some of that spending was on imports, goods that were not produced domestically. So we subtract imports from national spending to get national spending on domestically produced goods, C+I+G – Imports.

…Here is a mistake to avoid. The national spending approach to calculating GDP requires a step where we subtract imports but that doesn’t mean that imports are bad for GDP! Let’s consider a simple economy where I, G, and Exports are all zero and C=$100 billion. Our only imports come from a container ship that once a year delivers $10 billion worth of iPhones. Thus when we calculate GDP we add up national spending and subtract $10 billion for the imports, $100-$10=$90 billion. But suppose that this year the container ship sinks before it reaches New York. So this year when we calculate GDP there are no imports to subtract. But GDP doesn’t change! Why not? Remember that part of the $100 billion of national spending was $10 billion spent on iPhones. So this year when we calculate GDP we will calculate $90 billion-$0=$90 billion. GDP doesn’t change and that shouldn’t be surprising since GDP is about domestic production and the sinking of the container ship doesn’t change domestic production.

We continue:

If we want to understand the role of imports (and exports) on GDP and national welfare. We have to go beyond accounting to think about economics. If we permanently stopped all the container ships from delivering iPhones, for example, then domestic producers would start producing more cellphones and that would add to GDP but producing more cellphones would require producing less of other goods. If we were buying cellphones from abroad because producing them abroad requires fewer resources then GDP would actually fall—this is the standard argument for trade that you learned in your microeconomics class. The standard answer could change, however, if there were lots of unemployed resources, an issue we will discuss in Chapter 32 and later chapters. The point we want to emphasize here is not whether trade is ultimately good or bad but rather that Y+C+I+G+NX is an accounting identity that can’t by itself answer this question.

*Bull Shit Jobs: A Theory*

That is the new and entertaining book by David Graeber, probably you already have heard of it. Here is a brief summary.

Coming from academia, I am sympathetic to the view that not everyone is productive, or has a productive job. And my ongoing series “Those new service sector jobs…” is in part reflecting the wonder of the market in providing so many obscure services, but also in part a genuine moral query as to how many of these activities actually are worthwhile. You are supposed to have mixed feelings when reading those entries, just as with “Markets in Everything.”

Still, I think Graeber too often confuses “tough jobs in negative- or zero-sum games” with “bullshit jobs.” I view those as two quite distinct categories. Overall he presents the five types of bullshit jobs as flunkies, goons, duct tapers, box tickers, and taskmasters, but he spends too much time trying to lower the status of these jobs and not enough time investigating what happens when those jobs go away.

He doubts whether Oxford University needs “a dozen-plus” PR specialists. I would be surprised if they can get by with so few. Consider their numerous summer programs, their need to advertise admissions, how they talk to the media and university rating services, their relations with China, the student lawsuits they face, their need to manage relations with Oxford the political unit, and the multiple independent schools within Oxford, just for a start. Overall, I fear that Graeber’s managerial intelligence is not up to par, or at the very least he rarely convinces me that he has a superior organizational understanding, compared to people who deal with these problems every day.

A simple experiment would vastly improve this book and make for a marvelous case study chapter: let him spend a year managing a mid-size organization, say 60-80 employees, but one which does not have an adequately staffed HR department, or perhaps does not have an HR department at all. Then let him report back to us.

At that point we’ll see who really has the bullshit job.

One estimate of the rate of return on pharma

…return on investment in pharma R&D is already below the cost of capital, and projected to hit zero within just 2 or 3 years. And this despite all efforts by the industry to fix R&D and reverse the trend.

That is from Kelvin Stott. Keep in mind this is during a time when global demand has been growing, which suggests the supply side is all the more constipated.

The Rise of Market Power?

I am referring to the new Jan De Loecker and Eeckhout paper that is starting to get some buzz (ungated versions here). Their major result, quite simply, is:

In 1980, average markups start to rise from 18% above marginal cost to 67% now.

That sounds like big news, and probably it is. But I don’t think the authors are doing enough to interpret their results. There are two ways these mark-ups go could up: first there may be more outright monopoly, second there may be more monopolistic competition, with high mark-ups but also high fixed costs, and firms earning close to zero profits. The two scenarios have very different distributional implications, and different policy implications as well.

Consider my local Chinese restaurant. Maybe the fixed cost of a restaurant has gone up, due to rising rents and the need to invest in information technology. That can mean higher fixed costs, but still a positive mark-up at the margin. The marginal meal ordered there probably is taken from food inventory, representing almost pure profit. They are happy when I walk in the door! Yet they are not getting super-rich, rather they are earning the going risk-adjusted rate of return.

Now, if the economy is moving more toward monopolistic competition, higher mark-ups don’t explain other distributional changes in the macro data, such as the decline of labor’s share, as cited by the authors.

The authors consider whether fixed costs have risen in section 3.5. They note that measured corporate profits have increased significantly, but do not consider these revisions to the data. Profits haven’t risen by nearly as much as the unmodified TED series might suggest. I do see super-high profits in firms such as Google and Facebook, however. Those companies for the most part have lowered margins compared to the status quo ex ante when the relevant service cost infinity. “Mark-ups over time” measurements become very tricky when new products are being introduced.

The authors argue that the rising value of the stock market (plus dividends) is further evidence for rising profits. Maybe, but keep in mind that the public market is less and less representative of corporate America. It also has significant survivorship bias, based on size, as superfirms are rising and the number of small and mid-sized companies listing has plummeted since the 1980s. I suspect what has really happened is that large firms are way more profitable, partly because of globalization, not because they are doing such a major rip-off of American consumers. In most areas we have more choice, maybe much more choice, than before. I would be very surprised if it turned out that most good ol’ normal mid-sized service sectors firms saw a nearly fourfold increase of the profit rate relative to gdp since 1980, as the authors are suggesting might be true for the American economy as a whole. Health care, maybe, I grant that.

Or consider old-style manufacturing. The authors report that “Markups have gone up in all industries…” This is in an environment where numerous other highly credible empirical pieces, backed also by good anecdotal observation, cite rising competition from Chinese and other global suppliers. How does that all square? I side with David Autor on that one, yet it is reported that those mark-ups, in the sectors where American business now competes with the Chinese, are rising as measured. I am worried the paper does not at all try to square this tension. Surely it means the measures are significantly wrong in some way.

Similarly, the time series for manufacturing output is a pretty straight upward series, especially once you take out the cyclical component. If there is some massive increase in monopoly power, where does the resulting output restriction show up in that data? Once you ask that simple question, the whole story just doesn’t add up.

Or ask yourself a simple question — in how many sectors of the American economy do I, as a consumer, feel that concentration has gone up and real choice has gone down? Hospitals, yes. Cable TV? Sort of, but keep in mind that program quality and choice wasn’t available at all not too long ago. What else? There are Dollar Stores, Wal-Mart, Amazon, eBay, and used goods on the internet. Government schools. Hospitals. Government. Did I mention government?

I do think concentration in the American economy is up modestly, as I argue in The Complacent Class, and probably profits are up too, including relative to gdp. Hospitals are the most significant practical problem in this regard, and again that squares with the anecdotal evidence. As it stands, I don’t yet see that this paper has established its central claim that measured rising mark-ups indicate truly higher profits in a significant way.

Addendum: The section on macroeconomic implications I think is premature (they cite the declining labor share, declining capital share, decline of low skill wages, declining LFP, declining labor market flows, declining migration rates, and slower productivity growth). They should try to calibrate this, to see if the postulated effects possibly might work out as suggested, and by the way RBC research really is useful. And timing matters too! Given the mechanisms the authors cite, what kind of timing lags are possible? It would seem for instance that when mark-ups rise, real wages fall right then and there, due to the higher prices. Is that what the data show? Do the productivity growth effects, and their weird timing with 1973 and 1995-2004 breaks, fit into the same framework? And so on. I would be very surprised if the pieces fit together in even a crude sense.

And here are remarks by Rohan Shah. I thank Alex and Robin for useful comments and discussion, of course without implicating them.

How to think about charity: my response for Jeff Bezos

I was sent an email asking what I myself thought of the recent Jeff Bezos charity query, and that email contained a number of questions. I’m not at liberty to reproduce it, but with some minor edits I think you will be able to make sense of my responses, as given here:

- Since the marginal value of extra consumption by him (or even far less wealthy people) is essentially zero, there are many “good enough” charitable ventures.

- The rate of abandonment is high for charitable support.

- Often the key is for a super-productive person, with lots of stimulating opportunities at his or her disposal (if only running the status quo businesses, or say meeting other famous people), is to find something charitable that will hold his or her interest. But how can it possibly be as fun as the earlier successes and extending them?

- I disagree with your descriptions of the philanthropic strategies offered in your email. I suspect that most or all are attempted examples of my #3, namely what is actually short-run thinking.

- They are all super short-term strategies, once the attention constraint is measured.

- In this regard, there is nothing strange about Bezos’s plea and expressed desire to do some good in the short term, except its transparency.

- Perhaps earlier philanthropists, such as Carnegie, had many fewer opportunities for fun, if only because their times were so primitive and backward. That made it easier for them to keep up enthusiasm for truly long-term projects.

- I still think the real opportunities are for *true* long-run thinking, admittedly subject to the constraint that it keeps one’s short-term interest up.

- Cultivating one’s own weirdness, or having a lot of it in the first place, is one way to ease the congruence I mention in #8.

- Even truly smart and wise people often “give to people” rather than to projects. This is for one thing a strategy for keeping one’s own interest up.

So to tie this all back in to Jeff Bezos, I don’t know what he should do. I don’t know him personally, nor do I even have an especially strong knowledge of the second-hand sources about him.

But I think he is exactly on the right track to be thinking about what motivates him personally, and what is likely to hold his attention. And I don’t think his approach is any more “short term” than most of the other philanthropy of the super-rich.