Results for “stagnation” 721 found

The Great Relocation or the Great Stagnation?

From a very good and thoughtful post by Noah Smith, here is one set of excerpts but do read the whole thing:

The idea, in a nutshell, is that economic activity is relocating from rich Europe, America, and Asia to developing Asia faster than technological progress can replenish it…

Note that although this Great Relocation is an alternative to Tyler Cowen’s Great Stagnation, it does not preclude it. Lower productivity growth could coexist alongside agglomeration effects. Or…they might even go together. As I wrote in an earlier post, some “endogenous growth” theories suggest that the availability of cheap labor can reduce the incentives for innovation. If technological progress has stalled, it might just be because the Great Relocation has taken priority.

…So China “took our jobs.” But this was not due to their exchange rate policy, or their export subsidies, or their willingness to pollute their rivers and abuse their workers, although all these things probably speed the transition. They took our jobs because it made no sense for a farm like the U.S. to be building the world’s cars and fridges in the first place. Forcing China to revalue the yuan might slow the Great Relocation a little, but has zero hope of stopping it.

Arnold Kling has related posts as well, focusing on factor price equalization rather than relocation. A few points in response:

1. Median income begins to stagnate in 1973, before this trend is significantly underway.

2. I do not see these forces — however strong they may be (and I am not sure) — as separate from a stagnation hypothesis. If you read the first excerpted sentence, it compares the speed of the relocation to the speed of (American) technological progress. I am focusing on the latter deficiency, without pretending it is our only problem.

3. I find Smith’s policy suggestions intriguing. They include more immigration (which suddenly acquires a new urgency), more urban density (ditto), and better roads, to boost nation-wide agglomeration effects.

The *greater* stagnation

Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson write:

The new estimates imply that America’s real income per capita dropped by about 22% over the quarter century 1774-1800, a decline almost as steep as during the Great Depression between 1929 and 1933, and certainly longer. If the 1790s recorded brisk growth rates (Sylla 2011: pp. 81-3), it follows that the Revolutionary War period could have been America’s greatest income slump ever. That fall may have been 28% or even higher in per-capita terms.

Factors behind this decline include the Revolutionary War, the lagging South, and a negative trade effect. The article is interesting throughout, for instance:

In 1774 the colonial South had about twice the per-capita income of New England, even when one rightly counts slaves as in the population. The absolute economic decline of the South Atlantic over the last quarter of the 18th century and its relative decline over the subsequent four decades stand out as an example of what has come to be called reversal of fortune (Acemoglu et al. 2002). By 1840 the South Atlantic was well behind the Northeast, having been well ahead in 1774, and its population share of the original thirteen colonies had fallen too. Furthermore, we can find no evidence that the colonial South had any large army of poor whites in 1774; indeed, Southern free labour had some of the highest wages anywhere in the colonies. Thus, it appears that the ubiquity of poor whites in the South was strictly a nineteenth-century phenomenon, associated, presumably, with post-1774 decades of very poor growth. Why the reversal of fortune for the South? We are still not sure whether it was bad luck in its export commodity markets, institutional failure, or exceptionally severe wartime damage.

There is No Great Stagnation

Greenhouses lined with genetically modified marijuana sit on a mountainside just an hour ride from Cali, Colombia, where farmers say the enhanced plants are more powerful and profitable.

One greenhouse owner said she can sell the modified marijuana for 100,000 pesos ($54) per kilo (2.2 pounds), which is nearly 10 times more than the price she can get for ordinary marijuana.

Here is more and for the pointer I thank MT.

The Great (Male) Stagnation

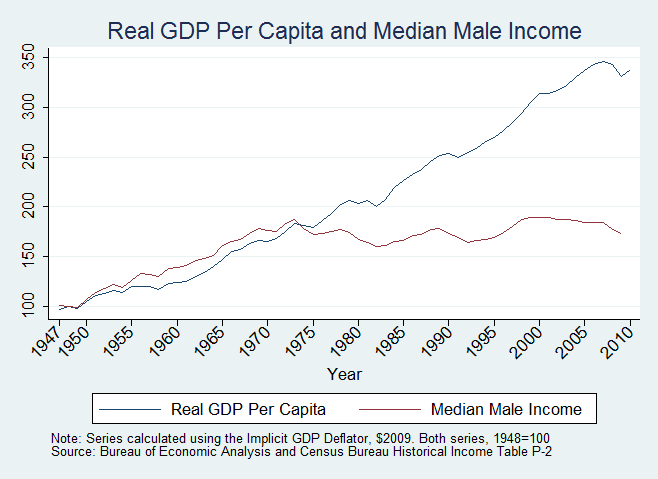

You have probably seen something like the following graph which shows real GDP per capita and median male income since 1947. Typically, the graph is shown with family or household income but to avoid family-size effects I use male income. It’s evident that real gdp per capita and median male income became disconnected in the early 1970s. Why? Explanations include rising inequality (mean male income does track real gdp per capita somewhat more closely), Tyler speculates that the nature of technological advances has changed, other people have speculated about rising corporate profits. Definitive answers are hard to come by.

Here is another set of data that most people have not incorporated into their analysis:

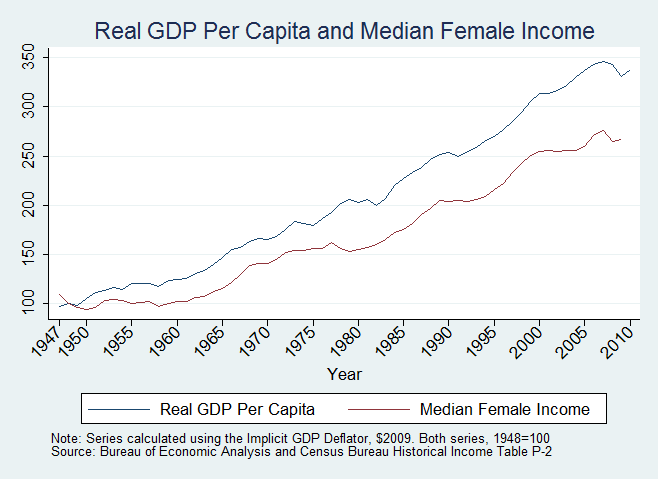

Median female income tracks real GDP per capita much more closely than does median male income. It’s unclear which, if any, of the above explanations are consistent with this finding. Increasing inequality, for example, predicts an increasing divergence in real GDP per capita and female median income but we don’t see this in the graph (there is a slight increase in the absolute difference but the ratios don’t increase). Similarly, we would expect changes in technology and corporate profits to affect both male and female median income equally but in fact the trends are very different.

One can, of course, do the Ptolemaic move and add an epicycle for differences in male and female inequality and so forth. Not necessarily wrong but not that satisfying either.

The big difference between female and males as far as jobs, of course, has been labor force participation rates, increasing strongly for the former and decreasing somewhat for the latter. Most of the female change, however, was over by the mid to late 1980s, and the (structural) male change has been gradual. Other differences are that female education levels have increased dramatically and male levels have been relatively flat. Females are also more predominant in services and males in manufacturing: plumbers, car mechanics, carpenters, construction workers, electricians, and firefighters, for example are still 95%+ male. Putting these together points to a skills and sectoral story, probably amplified by follow-on changes in labor force participation rates.

Thinking about the story this way also reminds us that the median male or female is not a person but a place in a distribution. The median male in 1970 can get rich by 1990 even though median male income is flat.

Again, no definitive answers, but the raw patterns are striking.

Note: An extra high tip of the hat to Scott Winship who whipped up all of the data during a discussion.

My TEDx talk on The Great Stagnation

You will find it here.

And tomorrow the physical version of the book is available from Amazon, Barnes&Noble.com, and in book stores.

*The Great Stagnation* (Retrogression)

June 9 it is coming out in a physical edition, hard cover. Amazon pre-order is here. Barnes&Noble pre-order is here. The text is exactly the same as the eBook edition, although I made a minor addition to one footnote. If you’ve read Borges’s Pierre Menard, you’ll know why I regard the electronic edition as “the real book” and this volume as a kind of postmodern satire. Still, many people demanded a physical edition, sometimes for classroom use, and so now there is one.

Three (unrelated?) points about stagnation

I’ve been wondering about a few questions.

Internalizing externalities is a common theme in economics,and it’s also called capturing the value you create. Don’t economists believe this happens — and happens increasingly — all the time? Karl Smith writes (and you can find his caveat here):

TFP growth depends on the returns to innovation not being captured by the innovator. Otherwise it becomes a return to the factor of production rather than total factor productivity.

Does TFP tend to fall once it has been high for a while? Is falling TFP, following a technological breakthrough, a sign of the market’s ability to capture value and internalize externalities? And is this another reason why we might prefer imperfectly defined intellectual property rights?

The second question concerns the Industrial Revolution. There is a large cottage industry about the origins of “the rise of the West,” and so on. I am not disputing the particular causal claims made in this literature. Still, I wonder what is being explained. Arguably the potency of the technological platform of “powerful machines plus fossil fuels” was not well understood in advance. Ex post, that it led to the “rise of the modern world” was somewhat of a technological accident. In this sense, studies of the origins of the Industrial Revolution, analytically speaking, are explaining “the Industrial Revolution” (to some extent). But the “sense-reference distinction” matters here. These studies are not so much explaining “the rise of the modern world,” which is more of a technological accident than we might wish to think.

Third, there remains the issue of unmeasured gains in real wages. Let’s try a simple thought experiment. Say I’ve been at George Mason twenty years (much less since 1973) and my real wage had never gone up (not the case). But my Dean were to say to me: “Tyler, U.S. health care has some new procedures, when you’re 73 you’ll have stents, and now can surf the internet and watch reruns of Battlestar Galactica. We’ve treated you very well!” Such a claim would not pass the laugh test and few people would accept it as applied to their own employment relation. Yet many of those same people make this same argument in the aggregate. I still think that if measured real wages for a group (or individual) have not gone up very much, over a long period of time, something is wrong. Wrong with the Dean, wrong with me, whatever, but something is wrong. Who would have predicted in 1972 that measured male median wages were going to stagnate and even possibly fall? You should be shocked by this result and indeed I am.

The culture that is Japan there is no great stagnation

Japanese invent a box that can simulate a kiss over the Internet:

The device looks like an ordinary box attached to a computer with a rotating straw. A closer look reveals otherwise. Students at Japan’s Kajimoto Laboratory at the University of Electro-Communications have created a small device that uses motor rotations with the aim to simulate the feeling of a kiss over the Internet. Warning: this might be the most disturbing thing you’ll see today.

Upon closer inspection, we learn that the kissing device responds directly to a person’s tongue. On one end, a person rotates the “straw” in one direction and the “straw” on the other end will rotate in the same direction. The result is a powerful tactile response that feels like you’re giving or receiving a kiss. From the demonstration video, the device looks a lot more effective than that concept cellphone that uses a wet sponge to transmit moisture onto a person’s lips.

For the device’s creators at Kajimoto Laboratory, the kissing device has a lot of potential, “The elements of a kiss include the sense of taste, the manner of breathing, and the moistness of the tongue…

But where is the demonstration video? Can you find it on the site or elsewhere?

For the pointer I thank Natalie B.

The Great Stagnation, in agriculture

Overall, it is neglected knowledge just how much the “Green Revolution” has slowed down since the 1990s. In Africa, measured heights have stagnated or declined in recent times. Robert Paarlberg’s Starved for Science: How Biotechnology is Being Kept Out of Africa is an excellent book on its title topic and more generally on falling TFP in global agriculture.

On other commodities, there are further charts and graphs (on both sides of the debate) here. The article is overwrought but worth the read, as it shows how far we are currently from the world of Julian Simon.

The Great Stagnation, a continuing story

The Education Department did not go nearly as far as college leaders would have liked in backing away from a new rule requiring colleges to get approval from every state in which they operate distance education programs. But in announcing Tuesday that, for the next three years, the agency would not meaningfully punish institutions that have shown “good faith” efforts to get such approval…

Do you need to read further? Abolish the DOE, I say. The full, messy, and heartbreaking story is here.

*The Great Stagnation* debate with Rob Atkinson

You can watch it here, MP3 version here. By the way, Rob’s group, ITIF, has put out this working paper on the economic benefits of information technology, and this working paper on whether productivity growth still benefits average Americans.

No Great Stagnation: TV Remote Control Device, 1976

*Economist* symposium on *The Great Stagnation*

You will find it here, with contributions from Viral Acharya, Scott Sumner, Hal Varian, and Paul Seabright. From elsewhere, Noah Smith cautions economists not to invoke technology too often. Brad DeLong chimes in. From a few years ago, Austan Goolsbee measures the consumer surplus from the internet; his numbers do not refute the standard view that median income growth has become much much slower.

Canadian data on income stagnation

The median earnings of full-time Canadian workers increased by just $53 annually — that's right, $53 annually — between 1980 and 2005.

Here is more, or here. This is one reason why I do not adhere to some of the progressive or "class struggle" explanations of relative stagnation in median income growth. Canada is not ruled by the so-called Republican Right.

There is another reason I don't buy the redistributive theory: here is a chart on The Great Stagnation of Capital.

The "class struggle" hypothesis makes at least some sense for 2001-2004, when measured productivity is high but the gains do not accure to the median. It does not make sense for the last forty years as a whole, or for the international evidence across countries.

Investment implications of The Great Stagnation

1. Slow revenue growth means that fiscal crises will be more severe than expected.

2. The deeper point is that the revenue growth/utility growth gradient has fundamentally changed, due to the "real shock" (as they call it) of the internet. Facebook is fun but it doesn't produce a proportional amount of revenue, and ultimately that has implications for asset pricing.

3. The change in this gradient means that a downturn hurts less, and that in turn means we will have more recessions and more asset price bubbles. Investors will take more chances, in part because safe returns are lower and in part because financial loss hurts less, in utility terms, than it used to.

4. Since the MU of money is now lower in downturns, the equity premium will fall. Risk premia will fall. Risk-taking will be less rewarded, because the destruction of one's finances is not as bad as it used to be.

5. If threshold savings is not an issue for you (e.g., needing to save a certain amount to put a kid through college), you should consider higher levels of consumption as a response to The Great Stagnation. Real rates of return on savings will not be fantastic, and risk-taking will be rewarded less. Spending is one sure way to get your money's worth.

6. I have other thoughts on this topic.