Month: September 2015

Just how guilty is Volkswagen?

I have a few points:

1. There is decent evidence that many other car companies have done something similar. Read this too. Besides, Volkswagen committed a related crime in 1973. When I was a teenager (maybe still?), it was commonly known that New Jersey service stations would help your car pass the emissions test if you slipped them a small amount of money. So we shouldn’t be shocked by the new story. The incentive of the agencies is to get the regulations out the door and to avoid subsequent bad publicity, not to actually solve the problem. So yes, there is a “regulation ought to be tougher” framing, but there is also a “we’ve been overestimating the benefits of regulation” framing too. Don’t let your moral outrage, which leads you to the former lesson, distract you from absorbing some of the latter lesson too.

2. We are more outraged by deliberate attempts to break the law, compared to stochastic sloppiness leading to mistakes and accidents. But it is far from obvious that the egregious violations should be punished more severely in a Beckerian framework. In fact, if they are harder to pull off, compared to sheer neglect, perhaps they should be punished less severely, at least from a utilitarian point of view. I am not saying we should discard our intuitions about relative outrage, but we ought to look at them more closely rather than just riding them to a quick conclusion. I’ve seen it noted rather frequently that the head of the supervisory committee at Volkswagen is named Olaf Lies.

3. Don’t think this is just market failure, it springs from a rather large government subsidy program. Clive Crook makes a good point:

Remember that “clean diesel” was a government-led initiative, brought to you courtesy of Europe’s taxpayers. And, by the way, the policy had proved a massively expensive failure on its own terms even before the VW scandal broke.

…At best, the clean-diesel strategy lowered carbon emissions much less than hoped, and at ridiculous cost; at worst, as one study concludes, the policy added to global warming.

4. One back of the envelope estimate is that the added pollution killed 5 to 23 Americans each year. Now I don’t myself think we should always or even mostly use economic methods to value human lives. But if you wish to play that cost-benefit game, maybe here we have $25 million to $100 million in economic value a year destroyed. It’s not uncommon to spend $100 million marketing a bad Hollywood movie. So in economic terms (an important caveat), this is a small event. Most of the car pollution problem comes from older vehicles with poor maintenance, not fraud on the newer tests. It also seems (same link) that diesel engines are 95% cleaner since the 1980s.

5. The German automobile sector exported about $225 billion in 2014. That’s almost as big as Greek gdp.

6. Manipulated data will be one of the big, big stories of the next twenty years, or longer.

7. It is worth citing Glazer’s Law, which is designed to classify explanations for microeconomic puzzles: “It’s either taxes or fraud”

This one isn’t taxes.

China fact of the day

The country’s stocks listed in Hong Kong are trading below book value…

The full FT story by James Mackintosh is here.

Generic Drug Regulation and Pharmaceutical Price-Jacking

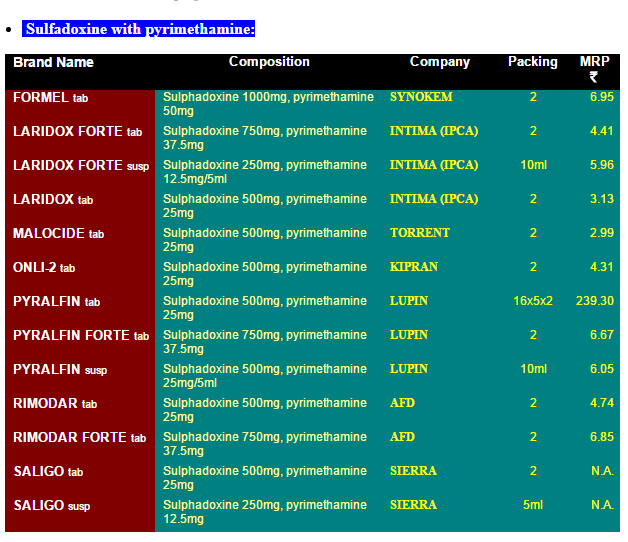

The drug Daraprim was increased in price from $13.60 to $750 creating social outrage. I’ve been busy but a few points are worth mentioning. The drug is not under patent so this isn’t a case of IP protectionism. The story as I read it is that Martin Shkreli, the controversial CEO of Turing pharmaceuticals, noticed that there was only one producer of Daraprim in the United States and, knowing that it’s costly to obtain even an abbreviated FDA approval to sell a generic drug, saw that he could greatly increase the price.

It’s easy to see that this issue is almost entirely about the difficulty of obtaining generic drug approval in the United States because there are many suppliers in India and prices are incredibly cheap. The prices in this list are in India rupees. 7 rupees is about 10 cents so the list is telling us that a single pill costs about 5 cents in India compared to $750 in the United States!

It is true that there are real issues with the quality of Indian generics. But Pyrimethamine is also widely available in Europe. I’ve long argued for reciprocity, if a drug is approved in Europe it ought to be approved here. In this case, the logic is absurdly strong. The drug is already approved here! All that we would be doing is allowing import of any generic approved as such in Europe to be sold in the United States.

Note that this is not a case of reimportation of a patented pharmaceutical for which there are real questions about the effect on innovation.

Allowing importation of any generic approved for sale in Europe would also solve the issue of so-called closed distribution.

There is no reason why the United States cannot have as vigorous a market in generic pharmaceuticals as does India.

Hat tip: Gordon Hanson.

Thursday assorted links

1. Competing to write the smallest chess program (hate).

2. Smart camera stops you from taking ordinary, cliched photographs.

3. Clifford Asness on carried interest.

4. A critique of the sexual assault survey.

5. Animals attacking drones (video).

6. Is the world running out of workers? (speculative, and probably wrong, but worth a read) And how does the welfare state affect the family?

Breaking Bad: Are Meth Labs Justified in Dry Counties?

A new paper from Fernandez, Gohmann and Pinkston shows that counties in Kentucky that forbid alcohol have more meth labs than otherwise similar counties. I like the research but in truth any paper with both Breaking Bad and Justified references is a winner in my book.

Abstract: This paper examines the influence of local alcohol prohibition on the prevalence of methamphetamine labs. Using multiple sources of data for counties in Kentucky, we compare various measures of meth manufacturing in wet, moist, and dry counties. Our preferred estimates address the endogeneity of local alcohol policies by using as instrumental variables data on religious affiliations in the 1930s, when most local-option votes took place. Alcohol prohibition status is influenced by the percentage of the population that is Baptist, consistent with the “bootleggers and Baptists” model. Our results suggest that the number of meth lab seizures in Kentucky would decrease by 24.4 percent if all counties became wet.

The authors suggest that alcohol users who buy alcohol in places where it is banned become acculturated and familiar with illegal networks making it easier for them to buy meth. In a reverse of the usual story, alcohol prohibition becomes the gateway to other illegal activities.

In my interpretation, however, the association of meth labs and alcohol prohibition is due more to supply side factors than demand side factors. In particular, a long history of moonshine production in dry Kentucky counties leads to an accumulation of knowledge about where to hide the labs, how to evade the law and who to bribe. In this version of the theory, lifting alcohol prohibition doesn’t necessarily reduce meth production because the knowledge and the networks remain in place.

A modified version of the theory can combine demand and supply factors. If there are economies of scope between alcohol production and meth production (such as bribes to local police) then a reduction in the demand for moonshine will raise the costs of producing meth.

Understanding which of these theories holds would make an important contribution to the industrial organization of illegal goods and would also have implications for how best to combat illegal good production.

Are pharmaceutical drug prices too high?

Hillary Clinton has proposed a new plan to bring down prescription drug prices, but so far the reception is cool. Here is one comment:

But when I ran it by some health economists and other health policy experts, several strongly disliked the idea because it misunderstands the diversity of companies in the pharmaceutical industry. They say it would create perverse incentives that could raise instead of lower the costs of developing new drugs.

“This is an astonishingly naïve approach,” said Amitabh Chandra, a professor of public policy at Harvard University, in an email. He argues that the plan could encourage wasteful research spending without necessarily doing much about the prices charged for medications.

That is from Margot Sanger-Katz at the NYT, not the Heritage Foundation.

I would stress a different point, and this concerns pharmaceutical prices more generally, not just the Clinton plan. Higher prices induce more innovation, and those innovations benefit patients in many countries. Note that connection is true even if you think most innovations come from universities or the NIH rather than being hatched Big Pharma. There is still a pot at the end of the rainbow for the significant innovators in this process.

OK, so how much does innovation go down if prices go down?

Here is an earlier post by Alex on Frank Lichtenberg’s estimation: “Thus, price controls or other restrictions that reduce prices are almost certainly a bad idea.”

Here is another earlier post by Alex, citing Megan, noting that Apple spends three cents of every dollar on R&D, and other inconvenient facts and that was from 2009.

If the advocate of lower drug prices does not have clear quantitative evidence for a conclusion of “lowering drug prices will not harm innovation very much,” commit the analysis to the flames, for it harbors nothing but sophistry and illusion. And while agnosticism about elasticities might weaken the argument for keeping prices high, that’s not an argument for lowering prices, that is an argument for agnosticism.

This same point applies to most commentaries on TPP I might add, and intellectual property analysis. Write it on the bathroom wall: “Without an elasticity, there is no answer.” And scream it from the rooftops while you are at it.

British inequality: not what you think

A new paper by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) shines a new light on how well the British tax system redistributes incomes over people’s lifetimes, in addition to using the cross-sectional approach. It presents several interesting findings. For a start, it finds that lifetime inequality in Britain has always been much lower than cross-sectional inequality (see first chart). This is because the poorest in any given year are not always poor for their entire lives; the IFS’s simulations suggest that those who, over the whole of their life, are in the lowest 10%, only spend an average of a fifth of their lifetimes at the bottom.

More startlingly, policies that increased or cut welfare expenditure appear to have had very little impact on lifetime inequality. For instance, while the benefit cuts of the late 1980s reduced benefits and increased cross-sectional inequality, it had a much more muted effect on lifetime inequality. And, similarly, although Gordon Brown’s massive expansion of means-tested tax credits in the 2000s reduced cross-sectional inequality, they had very little impact on cutting lifetime inequality.

The paper also finds that the redistribution performed by the British welfare state is, to a great extent, smoothing incomes over people’s lifetimes rather than over their entire lives. Whereas 36% of individuals receive more in benefits than they pay in tax in any given year, only 7% do so over their lifetimes. Over half of all redistribution is simply across peoples’ lifespans; the young pay in while they work, and take out when they retire (see second chart).

The post is from Free Exchange. I do not yet see the paper on the website of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, does anyone know what is up?

A Sephardic Jew from the former Ottoman empire

No, not Dani Rodrik, the guest for tomorrow’s Conversations with Tyler chat, rather Elias Canetti. As prep for Dani at 3:30 tomorrow (live stream), I thought I should read some more Canetti. Here are a few maxims from his The Secret Heart of the Clock:

At the edge of the abyss he clings to pencils

Curiosity diminishing, he could now start thinking

He reads only for appearances now, but what he writes is real

Newspapers, to help you forget the previous day

His disintegrating knowledge holds him together

China question of the day

Visits to medical institutions, hospital visits, and primary medical facilities are growing at 2.98%, 5.40%, and 1.56% respectively.

That is from Christopher Balding, read the whole post. And that is for an aging population and in a setting where the demand for health care is for structural reasons growing rapidly. Furthermore the use of traditional Chinese medicine is declining rapidly, fifteen percent this year from Balding’s citation.

Now let’s say the Chinese economy is about fifty percent services, though the exact number can be debated. And we know that manufacturing PMI is down seven months in a row.

What is your estimate of the overall rate of economic growth in China? The overall rate of growth six months or a year from now?

In the middle of this post you will find Scott Sumner on China’s growth.

Here is Krugman’s excellent post on how large China spillovers will be. I say watch for who is exposed to the sudden weekend ten to fifteen percent devaluation. Lots of other EM currencies have gone down by about that amount, why should China be so different or immune? The Chinese government isn’t going to spend trillions of dollars on fighting a losing battle in the currency wars, they are simply waiting for the right time for this to happen. Don’t be caught off-guard.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Should you be an insider or an outsider? With advice from Larry Summers.

2. Paul Krugman refers to a piece on New Deal bankers wanting higher interest rates.

3. Would leaving the EU make it easier for the UK to control its border? (no, shout from rooftops)

4. Video excerpt, Luigi Zingales on whether Pope Francis is overrated or underrated. And lots of cheating on emissions tests, not just Volkswagen. Speaking of cheating, Angus and I say North Carolina barbecue is in decline.

5. The polity that is New York City:”Custodians took home an average pay of $109,467 in the 2013-14 school year — and 634 of the city’s 799 custodians earned more than $100,000 in salary and overtime during that time, city payroll records show.”

6. What are the current restrictions on American travel to Cuba?

Environmental sentences to ponder

Our empirical subjects are public and private entities’ compliance with the U.S. Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act. We find that, compared with private firms, governments violate these laws significantly more frequently and are less likely to be penalized for violations.

That is from Konisky and Teodoro, via Robin Hanson.

*Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989*, by Bruce Elleman

I am delighted to have been reading this 2001 history, which is now one of my favorite books on China. It is perhaps the best background I know for understanding current Chinese foreign policy, even though it does not focus on foreign policy per se. Do you wish to understand why the 19th century was so traumatic for China? How the Opium Wars and Taiping rebellion fit together? Why Manchuria was once such a flash point for global affairs? (Has any region fallen out of the major news so dramatically?) How is this for a good sentence?:

The 1929 Sino-Soviet conflict is perhaps China’s least studied and understood war.

I learned something from every page, you can buy the book here.

The flash reading of the Caixin China general manufacturing purchasing managers’ index dropped to 47 points in September, down from 47.3 in August, marking the worst performance for the sector in 78 months.

A reading above 50 indicates improving conditions while a reading below 50 signals deterioration. The index has now indicated contraction in the sector for seven consecutive months.

How quickly do services have to be expanding for the entire Chinese economy to be growing at anything close to six percent?

The incidence of the ACA mandates

Here is Mark Pauly, with Adam Leive and Scott Harrington (NBER), this is part of the abstract:

We find that the average financial burden will increase for all income levels once insured. Subsidy-eligible persons with incomes below 250 percent of the poverty threshold likely experience welfare improvements that offset the higher financial burden, depending on assumptions about risk aversion and the value of additional consumption of medical care. However, even under the most optimistic assumptions, close to half of the formerly uninsured (especially those with higher incomes) experience both higher financial burden and lower estimated welfare; indicating a positive “price of responsibility” for complying with the individual mandate. The percentage of the sample with estimated welfare increases is close to matching observed take-up rates by the previously uninsured in the exchanges.

I’ve read so many blog posts taking victory laps on Obamacare, but surely something is wrong when our most scientific study of the question rather effortlessly coughs up phrases such as “but most uninsured will lose” and also “Average welfare for the uninsured population would be estimated to decline after the ACA if all members of that population obtained coverage.” The simple point is that people still have to pay some part of the cost for this health insurance and a) they were getting some health care to begin with, and b) the value of the policy to them is often worth less than its subsidized price.

You will note that unlike say the calculation of the multiplier in macroeconomics, the exercises in this paper are relatively straightforward. They also show that people exhibit a fairly high degree of economic rationality when it comes to who signs up and who does not.

It has become clearer what has happened: members of various upper classes have achieved some notion of “universal [near universal] coverage,” while insulating their own medical care from most of the costs of this advance. Those costs largely have been placed on the welfare of…the other members of the previously uninsured. So we’ve moved from being a country which doesn’t care so much about its uninsured to being…a country which doesn’t care so much about its (previously) uninsured. I guess countries just don’t change that rapidly, do they?

I fully understand that Obamacare has survived the ravages of the Republican Party, and it was barely attacked in the recent series of debates, and thus it is permanently ensconced, and that no better politically feasible alternative has been proposed. At this point, the best thing to do is to improve it from within. Still, there are good reasons why it will never be so incredibly popular.

Data on deductibles

Kaiser, a health policy research group that conducts a yearly survey of employer health benefits, calculates that deductibles have risen more than six times faster than workers’ earnings since 2010.

I would stress two points. First, the value of benefits is in some regards eroding, so those who wish to cite benefits as an answer to wage stagnation will encounter some push back from reality.

Second, I don’t see this factor cited often as a possible contributing force to the moderation of health care cost inflation in recent years. But perhaps it plays some role.

The NYT Reed Abelson article is here.

What I’ve been reading

1. Deep South, by Paul Theroux. It’s OK enough, but Theroux’s best writing was motivated by bile and unfortunately he has matured. Still, he can’t get past p.9 without mention Naipaul’s “rival book” A Turn in the South. My favorite Theroux book is his Sir Vidia’s Shadow, a delicious story of human rivalry and one of my favorite non-fiction books period.

2. Elmira Bayrasli, From the Other Side of the World: Extraordinary Entrepreneurs, Unlikely Places. A well-written, completely spot on analysis about how the quality of the business climate needs to be improved in emerging economies, and about how much potential for entrepreneurship there is. If economists were to do nothing else but repeat this message, the quality and usefulness of our profession likely would rise dramatically.

3. Michael White, Travels in Vermeer: A Memoir. Nominated in the non-fiction National Book Award category, I actually enjoyed reading this one, all of it except the parts about…Vermeer. It’s better as a memoir of alcoholism and divorce, interspersed with visits to art museums.

Tom Gjelten’s A Nation of Nations is an interesting “immigration history” of Fairfax County. I enjoyed Deirdre Clemente’s Dress Casual: How College Students Redefined American Style.

Jennifer Mittelstadt’s The Rise of the Military Welfare State is a useful history of how a social welfare state for the military was first created, for recruitment purposes, and then later dismantled.

I recommend L. Randall Wray’s Why Minsky Matters: An Introduction to the Work of a Maverick Economist, forthcoming in November. Minsky isn’t so readable, but Wray is. I’ve just started my review copy, I hope to report more on it soon.