Month: February 2017

Why do governments leak information?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is part of the argument:

Sometimes governments trade leaked information to reporters, to curry favor. Other times leaks are used to hurt rivals within the public sphere, or a leak can serve as a trial balloon to test the popularity of an idea. Leaks also may help a president’s Cabinet members build up their own internal empires, which can boost a president’s agenda.

Or the American government may want to inform its people about, say, drone operations in Yemen, but without having to answer questions about the details. In this regard, leaks may substitute for more direct congressional oversight, to the benefit of the executive.

In other words, leaks are part of how the government manages the press and maintains its own popularity. A leak can get a story onto the front page, or if the first leak did not create the right impression, the information flow can be massaged by yet another leak.

Leaks are also a way of threatening other governments, yet without the president putting all of his credibility on the line. For instance, it can be leaked that the national security establishment would be especially unhappy with a further expansion of Israeli West Bank settlements. That sends a message, yet without committing the American government to any particular response if the settlements proceed. Or leaks can signal to foreign terrorists or governments that we know what they are up to.

Of course, many leaks are unwelcome, such as when national security confidences are disclosed. Given that reality, why haven’t American governments worked harder to prosecute unwelcome leaks and leakers?

Well, if that policy were pursued successfully, the only leaks that would occur would be “approved” or government-intended leaks, and everyone would figure this out. The government could no longer use leaks as a way of providing information or making threats in a distanced manner with plausible deniability.

Leak-receiving media outlets would feel more like pawns, and they would distance themselves from the leaking administration. Leaks would end up not being so different from announcements, which would counter the very purpose of leaks. And so whistle-blowing leaks and also security-diminishing leaks get pulled into the mix and tolerated to some degree.

Much of the rest of the column considers how matters have been changing under both Obama and Trump, and not generally for the better.

Alas Kenneth Arrow has passed away

Here are various notices on Twitter, here are mentions on MR.

How disorderly is Sweden really?

Here is the latest, which is in the media but not being plastered all over my Twitter feed:

Just two days after President Trump provoked widespread consternation by seeming to imply, incorrectly, that immigrants had perpetrated a recent spate of violence in Sweden, riots broke out in a predominantly immigrant neighborhood in the northern suburbs of Sweden’s capital, Stockholm.

The neighborhood, Rinkeby, was the scene of riots in 2010 and 2013, too. And in most ways, what happened late Monday night was reminiscent of those earlier bouts of anger. Swedish police apparently made an arrest around 8 p.m. near the Rinkeby station. For reasons not yet disclosed by the police, word of the arrest prompted a crowd of youths to gather.

Over four hours, the crowd burned about half a dozen cars, vandalized several shopfronts and threw rocks at police. Police spokesman Lars Bystrom confirmed to Sweden’s Dagens Nyheter newspaper that an officer fired shots with intention to hit a rioter, but did not strike his target. A photographer for the newspaper was attacked by more than a dozen men and his camera was stolen, but ultimately no one was hurt or even arrested.

It remains correct that an American city such as Orlando typically will have more murders than all of Sweden in a year. But it is also important to process the distinction between objective and subjective metrics of disorder. A jaywalker in Germany disrupts public order and flouts norms more than is the case for a single jaywalker in New Jersey, for instance. Sweden is relatively orderly, in part, because the public and psychological reactions to acts of disorder are relatively severe and traumatic, even if those same acts might be perceived as less significant in other contexts. It is quite possible that Swedish norms are being threatened by the level of disorder currently in the country, even if to a Nigerian it all might seem absurdly neat and tidy.

There is also reasonable evidence that immigrants to Sweden are a major reason for the decline in the average quality of Swedish schooling and also Swedish PISA scores. In other contexts, we will be told that such variables are incredibly significant, but in this context the result ends up largely ignored.

The simplest metric, however, would simply be to poll citizens of Nordic and European countries who are familiar with Sweden, but don’t have direct self-interest at stake, and ask them if they want the immigration history of their country to go the Swedish route. I haven’t seen the data, but I believe the rate of “yes” on that one would be quite low. You could not say the same about Canada or Australia, I suspect, or for that matter the United States.

On this whole matter, I would not say that Trump’s remarks have been correct and for sure they have been irresponsible on the diplomatic front. Still, the overall presentation of his critics arguably has been further yet from the reality, and that is part of the reason why Trump finds such an audience.

What accounts for the cost disease?

The basic post is too long, but some of it is interesting and here is the best part:

The pattern of Cost Disease seems to be related to things that inextricably require the unsubstitutable labour and attention not just of human beings but of human beings somehow comparable to the buyer. (Americans, for the US focus of most of this discussion.) Education not only requires teachers who are part of the same cultural milieu as their students, but it requires the attention of the students themselves, and attention is inherently expensive. As the only thing that can be expensive in the final Strong Heaven, attention predictably gets more expensive in a culture that moves more and more toward general post-scarcity. Health care similarly requires local human involvement.

That is from Ansuz, via Matthew Fairbank. And here is Scott Alexander’s survey follow-up post.

David Brooks on *The Complacent Class*

The hard part is that America has to become more dynamic and more protective — both at the same time. In the past, American reformers could at least count on the fact that they were working with a dynamic society that was always generating the energy required to solve the nation’s woes. But as Tyler Cowen demonstrates in his compelling new book, “The Complacent Class,” contemporary Americans have lost their mojo.

Cowen shows that in sphere after sphere, Americans have become less adventurous and more static. For example, Americans used to move a lot to seize opportunities and transform their lives. But the rate of Americans who are migrating across state lines has plummeted by 51 percent from the levels of the 1950s and 1960s.

Americans used to be entrepreneurial, but there has been a decline in start-ups as a share of all business activity over the last generation. Millennials may be the least entrepreneurial generation in American history. The share of Americans under 30 who own a business has fallen 65 percent since the 1980s.

Americans tell themselves the old job-for-life model is over. But in fact Americans are switching jobs less than a generation ago, not more. The job reallocation rate — which measures employment turnover — is down by more than a quarter since 1990.

There are signs that America is less innovative. Accounting for population growth, Americans create 25 percent fewer major international patents than in 1999. There’s even less hunger to hit the open road. In 1983, 69 percent of 17-year-olds had driver’s licenses. Now only half of Americans get a license by age 18.

Here is the full piece.

Tuesday assorted links

The wisdom of Lee Ohanian

The area has become “the largest region for medical device manufacturing” in the world, says Faulconer, who explains that because of increasingly complex binational supply chains, “sometimes [one product] will cross the border two to three times.” UCLA’s Ohanian pegs the figure far higher: In some cases, he suggests, a product can cross the U.S.-Mexico border an astonishing 14 times before it goes to market. One study suggests that the average good exported from Mexico to the U.S. contains 40-percent American-made components. In the San Diego-Tijuana region, Solar Turbines, Kyocera International and Taylor Guitars are just a few of the companies that have facilities on both sides of the border.

Here is the full article, via the wisdom of Garett Jones.

Outline of the new Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler book

The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life, and here is the opening bit of the summary:

Human beings are primates, and primates are political animals. Our brains were designed not just to gather and hunt, but also to get ahead socially, often by devious means. The problem is that we like to pretend otherwise; we’re afraid to acknowledge the extent of our own selfishness. And this makes it hard for us to think clearly about ourselves and our behavior.

The Elephant in the Brain aims to fix this introspective blind spot by blasting floodlights into the dark corners of our minds. Only when everything is out in the open can we really begin to understand ourselves: Why do humans laugh? Why are artists sexy? Why do people brag about travel? Why do we so often prefer to speak rather than listen?

Like all psychology books, The Elephant in the Brain examines many quirks of human cognition. But this book also ventures where others fear to tread: into social critique. The authors show how hidden selfish motives lie at the very heart of venerated institutions like Art, Education, Charity, Medicine, Politics, and Religion.

Acknowledging these hidden motives has the potential to upend the usual political debates and cast fatal doubt on many polite fictions. You won’t see yourself — or the world — the same after confronting the elephant in the brain.

Due out January 1, 2018, of course this is essential reading.

Monday assorted links

1. There is no cutlery great stagnation.

4. Kevin O’Rourke on the return of the Irish border.

5. Obituary for Michael Novak (NYT).

6. Watson benched for cancer work?

7. Deviations from covered interest parity seem real and robust, at least these days. And how trade shocks make men less marriageable.

The Ethics of Price Discrimination

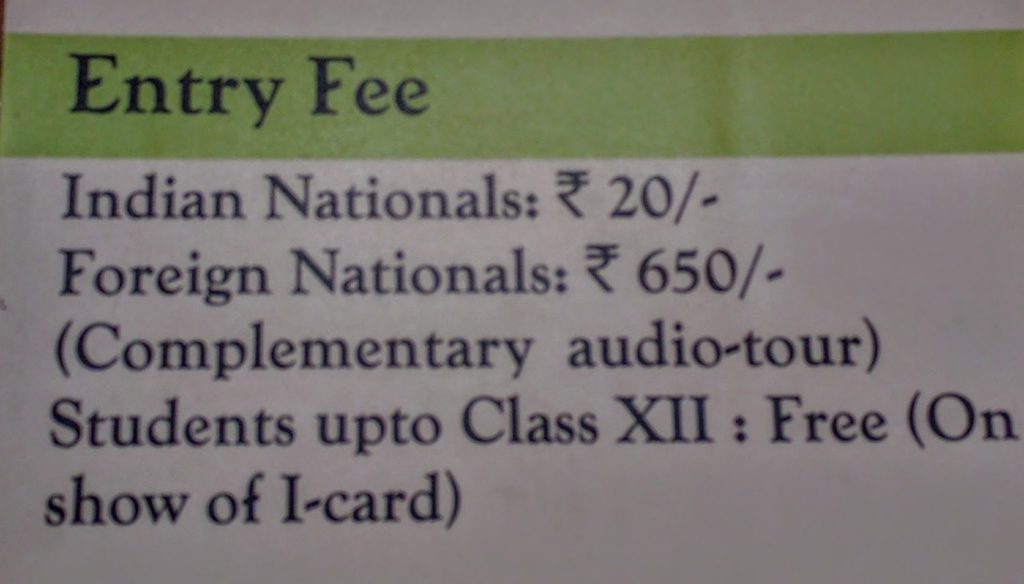

Here is an example of price discrimination from the National Museum of India in Delhi, India. Motivating question for discussion. Is this fair or ethical? Would it be legal in the United States?

America very rough calculation of the day those who walk amongst us

…only a tiny fraction of all living Americans ever convicted of a felony is actually incarcerated at this very moment. Quite the contrary: Maybe 90 percent of all sentenced felons today are out of confinement and living more or less among us. The reason: the basic arithmetic of sentencing and incarceration in America today. Correctional release and sentenced community supervision (probation and parole) guarantee a steady annual “flow” of convicted felons back into society to augment the very considerable “stock” of felons and ex-felons already there. And this “stock” is by now truly enormous.

…Very rough calculations might therefore suggest that at this writing, America’s population of non-institutionalized adults with a felony conviction somewhere in their past has almost certainly broken the 20 million mark by the end of 2016. A little more rough arithmetic suggests that about 17 million men in our general population have a felony conviction somewhere in their CV. That works out to one of every eight adult males in America today.

That is by Nicholas N. Eberstadt, via Arnold Kling. The broader piece is a useful litany of everything that has gone wrong since 1999 in this country.

Since the internet, do fewer researchers read research papers?

The obvious equilibrium is that more researchers can download papers from the internet, and thus we expect more papers to be read by a greater number of people. If lay people enter the calculus, this is almost certainly true. But what about researchers? I am not convinced that more reading (of each paper) goes on, or that it should go on.

Most people, including researchers, cannot easily figure out if the main result of a research paper is correct. That is true all the more as time passes, because the mistakes become less and less transparent. But they can figure out who can figure out if the paper is right, and sample that opinion. The internet aids this process greatly. For instance, it is easier for me to find out what Bob Hall (one of the great paper analysts/commentators of all time) thought of a macro paper, if only by using email. If I can find out whether or not the paper is true, often I don’t have to read that paper, though I may go through some parts of it. The internet also gives me access to better summaries of the paper, if only in parts of other papers.

In this sense, researchers may rely on a fairly thin substructure of evaluation, though one of increasing accuracy. As science progresses, perhaps scientists do/should spend more time honing their research specializations, and less time reading papers they are not expert evaluators for. They do/should spend more time reading the papers where they are the expert evaluators, but that may mean reading fewer papers overall.

Viewed as a productivity problem, perhaps your read is competing against “further spread of the read and evaluation from the best expert” and is losing. Efficient criticism is also sometimes winner take all.

I am indebted to Patrick Collison for a conversation on this topic, though of course he is not liable for any of this. Neither he nor I have read a paper on such matters, however. Thank goodness.

The Russian philosophy of combat

Here is one bit from an excellent longer piece by Michael Kofman:

Russia’s gradual approach is inherently vulnerable, since it is based around fielding the bare minimum amount number of troops in the battlespace to achieve desired political ends. In order to deter and dissuade peer adversaries Russia will often introduce high-end conventional capabilities, such as long range air defense, anti-ship missiles, and conventional ballistic missile systems. These weapons are not meant for the actual fight. Instead, they are intended to make an impression on the United States. The first goal of the Russian leadership is to make the combat zone its own sandbox, sharply reducing the options for peer adversaries to intervene via direct means. America does this in its campaigns by attaining air superiority. Russia’s method is cheaper: area denial from the ground.

…Beyond its political objectives, Russia places strong emphasis on having an exit strategy. In fact, a viable exit strategy seems just as important than whatever they are trying to achieve. It is perhaps one key point where Russia’s leaders would agree with Weinberger and Colin Powell. But unlike the United States, they actually practice it.

The pointer is from the always-astonishing The Browser.

Sunday assorted links

1. The economics and behavioral economics of pimping and recruiting prostitutes.

2. “This glass fits around your nose so you can smell wine as you drink it.” NB: the link serves up some noise to you.

3. “The state’s manual for execution procedures, which was revised last month, says attorneys of death row inmates, or others acting on their behalf, can obtain pentobarbital or sodium Pentothal and give them to the state to ensure a smooth execution.” Link here, that is Arizona.

4. Here is my old interview with Atlantic on my news diet. A few of you requested an update. These days it is more Twitter, fewer blogs, more Bloomberg View, and less reliance on news magazines (though some remain excellent). Inexplicably, on the first go-round I forgot to mention TLS and London Review of Books, I get Book Forum too Most of all, I rely more on what people email me and tell me about. Very recently, Twitter is more dramatic and sometimes more entertaining but also less useful for anything practical; my time allocation methods have yet to adjust but they will.

5. “It is possible to travel coast to coast—from, say, Coos Bay, Oregon, to Wilmington, North Carolina—without passing through a single county that Hillary Clinton won. Indeed there are several such routes.” That is from Christopher Caldwell. And new and long profile of Peter Navarro.

6. Workman’s cafe in France accidentally awarded a Michelin star. And Hong Kong food trucks show that economy really isn’t as free as you might think (NYT).

What I’ve been reading

1. Jean-Yves Camus and Nicholas Lebourg, Far-Right Politics in Europe. A very good and extremely current introduction to exactly what the title promises, with plenty on earlier historical roots.

2. Noo Saro-Wiwa, Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria. More or less a travelogue, but also one of the best introductions for thinking about Nigeria, and it does stress the different regions of the country. Both informative and entertaining.

3. The Maisky Diaries: The Wartime Revelations of Stalin’s Ambassador in London, edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky. Paul Kennedy called it the greatest political diary of the twentieth century. One of the best windows on the coming and arrival of the Second World War, and I don’t usually like reading the diary form. It’s also a very good look into how such an impressive person could be Stalin’s ambassador. By the way, why is the hardcover about a quarter of the price of the paperback?

4. Peter Leary, Unapproved Routes, Histories of the Irish Border, 1922-1972. Soon there may be one again, so I decided to read up on the background, a tale of Derry being severed from Donegal. This informative, easily grasped book also has a chapter on the fisheries border, a sign of the imaginativeness of the author.

5. Joseph J. Ellis, The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789. Ellis is consistently excellent as an author, and this book is best on tying the intellectual evolution of the Founding Fathers to the troubles of the Articles of Confederation period.

There is also a new Deirdre McCloksey festschrift, Humanism Challenges Materialism in Economics and Economic History, edited by Roderick Floyd, Santhi Hejeebu, and David Mitch. It appears to be a very fine tribute.

Stephen D. King has a new book coming out on the reversal of globalization, namely Grave New World: The End of Globalisation, The Return of History.