Month: October 2017

You too can now relax

People have stopped worrying about covered interest parity.

This worry has expired along with the cross-currency basis. Here’s Matt Klein at Alphaville explaining that for much of 2016, it was much cheaper to borrow dollars in the U.S. and hedge them into yen than it was to borrow yen in Japan, creating an obvious arbitrage that nonetheless didn’t go away. But then it did, due to declining dollar strength or the full phasing-in of money-market-fund reform or changes in Federal Reserve balance-sheet policy. I look forward to other recurring Money Stuff worries being so fully and satisfactorily resolved.

That is from the “no one else could do what he does” Matt Levine at Bloomberg. And Matt points out that Stephen Curry is reading Ray Dalio’s Principles.

The culture and polity that is China

Those who fail to repay a bank loan will be blacklisted, and they will have their name, ID number, photograph, home address and the amount they owe published or announced through various channels – including in newspapers, online, on radio and television, and on screens in buses and public lifts.

…In the southern city of Guangzhou, the personal details of some 141 debt defaulters have so far been displayed on screens in buses, commercial buildings and on media platforms at the request of local courts.

Meanwhile in Jiangsu, Henan and Sichuan provinces, the courts have teamed up with telecoms operators to create a recorded message – played every time someone calls – for those who fail to repay their loans. The message tells the caller: “The person you are calling has been put on a blacklist by the courts for failing to repay their debts. Please urge this person to honour their legal obligations.”

That is from SCMP, via Viking.

Elsewhere in the Middle Kingdom, Shanghai adopts a facial recognition system to name and shame jaywalkers.

American cities and suburbs are converging

That is the theme of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

The internet has been another equalizer. You can enjoy texting and social media from just about anywhere, and our near obsession with these activities is equalizing urban and suburban experiences, possibly for the worse.

Arguably, sex and alcohol were once more prominent in some American cities than in American suburbs. But the new generation of American youth seems less interested in these activities anyway.

As American travel infrastructure decays, and traffic congestion worsens, what we used to call cities and suburbs won’t be able to rely on each other so much, as trips become too exhausting and time-consuming. That too will encourage cities and suburbs each have their own mix of jobs, retail and cultural opportunities.

There is much more at the link.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Are positive and normative economics really all that different?

2. The movie The Florida Project is flawed, but its strengths are very strong.

3. Frakt and Carroll on health care and innovation (NYT).

4. New Macarthur winner Elizabeth [Betsy] Levy Paluck on what works in prejudice reduction. Here are more of her papers.

5. Decentralized credit scoring through a blockchain? (pdf)

Does Online Dating Increase Racial Intermarriages?

Today about a third of all new marriages are between couples who met online. Online dating has an interesting property–you are likely to be matched with a total stranger. Other matching methods, like meeting through friends, at church or even in a local bar are more likely to match people who are already tied in a network. Thus, the rise of online dating is likely to significantly change how people connect and are connected to one another in networks. Ortega and Hergovich consider a simple model:

We consider a Gale-Shapley marriage problem, in which agents may belong

to different races or communities. All agents from all races are randomly

located on the same unit square. Agents want to marry the person who is

closest to them, but they can only marry people who they know, i.e. to whom

they are connected. As in real life, agents are highly connected with agents

of their own race, but only poorly so with people from other races.

Using theory and random simulations they find that online dating rapidly increases interracial marriage. The result happens not simply because a person of one race might be matched online to a person of another race but also because once this first match occurs the friends of each of the matched couples are now more likely to meet and marry one another through traditional methods. The strength of weak ties is such that it doesn’t take too many weak ties to better connect formerly disparate networks.

Using theory and random simulations they find that online dating rapidly increases interracial marriage. The result happens not simply because a person of one race might be matched online to a person of another race but also because once this first match occurs the friends of each of the matched couples are now more likely to meet and marry one another through traditional methods. The strength of weak ties is such that it doesn’t take too many weak ties to better connect formerly disparate networks.

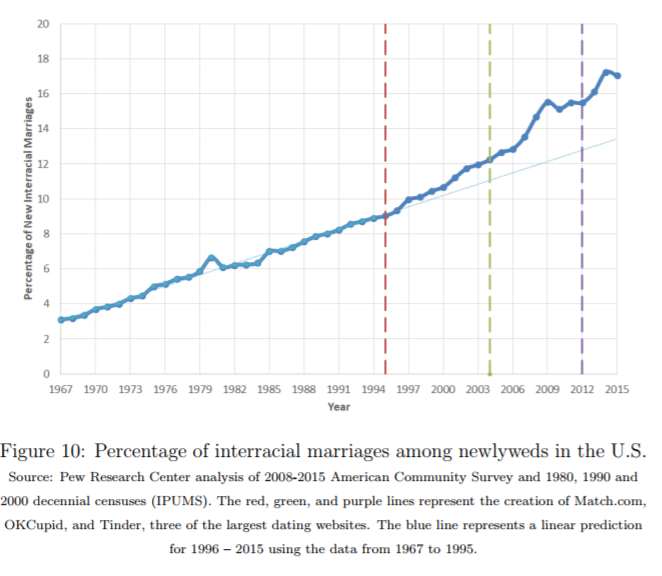

Interracial marriage, defined to include those between between White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian or multiracial persons, has been increasing since at least the 1960s but using the graph at right the authors argue that the rate of growth increased with the introduction and popularization of online dating. Note the big increase in interracial marriage shortly after the introduction of Tinder in 2009!

(The authors convincingly argue that this not due to a composition effect.)

Since online dating increases the number of potential marriage partners it leads to marriages which are on average “closer” in preference space to those in a model without online dating. Thus, the model predicts that online dating should reduce the divorce rate and there is some evidence for this hypothesis:

Cacioppo et al. (2013) find that marriages created online were less likely to

break up and reveal a higher marital satisfaction, using a sample of 19,131

Americans who married between 2005 and 2012. They write: “Meeting a

spouse on-line is on average associated with slightly higher marital satisfaction

and lower rates of marital break-up than meeting a spouse through

traditional (off-line) venues”

The model also applies to many other potential networks.

Hat tip: MIT Technology Review.

Celebrity Misbehavior

Casual empiricism suggests that celebrities engage in more anti-social and other socially unapproved behavior than non-celebrities. I consider a number of reasons for this stylized fact, including one new theory, in which workers who are less substitutable in production are enabled to engage in greater levels of misbehavior because their employers cannot substitute away from them. Looking empirically at a particular class of celebrities – NBA basketball players – I find that misbehavior on the court is due to several factors, including prominently this substitutability effect, though income effects and youthful immaturity also may be important.

Elsewhere, here is a Kaushik Basu micro piece on the law and economics of sexual harassment. And a more recent piece from the sociology literature. The practice increases quits and separations, with some of the costs borne by harassment victims and not firms; given imperfect transparency, recruitment incentives may not internalize this externality. On other issues, here is a relevant AER article. And this piece applies an insider-outsider model. Here is Posner (1999), perhaps he has changed his mind. Here is work by Elizabeth Walls, from Stanford.

I see negative externalities to sexual harassment across firms and sectors, and so, contra Posner (1999) and Walls, the most just and also efficient outcome is to tolerate one explicit and transparent form of the practice in the sector of formal prostitution and otherwise to keep it away from normal business activity. I believe such a ban boosts womens’ human capital investment, investment in firm-specific skills, aids the optimal production of status, and limits one particular kind of uninsurable risk, with all of those benefits correspondingly higher in an O-Ring or Garett Jones model of productivity.

The excellent Kevin A. Bryan on innovation

He has a forthcoming JET paper with Jorge Lemus, here is the abstract:

We construct a tractable general model of the direction of innovation. Competition leads firms to pursue inefficient research lines, because firms both race toward easy projects and do not fully appropriate the value of their inventions. This dual distortion will imply that any directionally efficient policy must condition on the properties of hypothetical inventions which are not discovered in equilibrium, hence common R&D policies like patents and prizes generate suboptimal innovation direction and may even generate lower welfare than laissez faire. We apply this theory to radical versus incremental innovation, patent pools, and the effect of trade on R&D.

Here is a slightly different version of the abstract, along with other research papers. Here is Kevin on travel. Kevin is at the University of Toronto, and also is author of the excellent blog A Fine Theorem.

Here is Kevin’s reading list on innovation, recommended.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Who’s complacent?: wine-infused coffee exists.

2. “Across a range of policy settings, people find the general use of behavioural interventions more ethical when illustrated by examples that accord with their politics, but view those same interventions as more unethical when illustrated by examples at odds with their politics.” Link here.

3. Microfoundations for the endowment effect?

4. After plastic surgery, three Chinese women are stuck at the South Korean airport.

5. Chinese scientists can identify you by your walk. And China’s AI awakening.

6. David Brooks on Thaler (NYT).

Do Parents Value School Effectiveness?

That is a new NBER Working Paper by Atila Abdulkadiroglu, Parag A. Pathak, Jonathan Schellenberg, and Christopher R. Walters, on a much understudied topic. Here are their main results:

School choice may lead to improvements in school productivity if parents’ choices reward effective schools and punish ineffective ones. This mechanism requires parents to choose schools based on causal effectiveness rather than peer characteristics. We study relationships among parent preferences, peer quality, and causal effects on outcomes for applicants to New York City’s centralized high school assignment mechanism. We use applicants’ rank-ordered choice lists to measure preferences and to construct selection-corrected estimates of treatment effects on test scores and high school graduation. We also estimate impacts on college attendance and college quality. Parents prefer schools that enroll high-achieving peers, and these schools generate larger improvements in short- and long-run student outcomes. We find no relationship between preferences and school effectiveness after controlling for peer quality.

You can read that as the parents either being super-smart about what helps their kids — better peers — or the parents being snobby per se. Either way, they don’t seem to care so much about value-added from the side of the school. Or is peer quality actually also the best practical-for-parents measure of value-added, when all is said and done?

So I say this is an inconclusive result from the final normative point of view, but a highly significant result in terms of cementing in some knowledge close to what I already expected was the case.

That was then, this is now: corporate tax rate cut edition

Obama proposes lowering corporate tax rate to 28 percent

That is circa early 2012, and presumably Obama’s CEA signed off on the idea. Romney at the same time proposed a rate of 25 percent.

I believe that, in a rush to criticize a proposed Trump tax cut, we are in danger of forgetting the wisdom of 2012.

Why “nudge” is more often than not a socially conservative idea

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, on Thaler and Sunstein, here is one excerpt:

There is a common pattern here: Society is unwilling to resort to outright, direct coercion either to keep people married or to keep them from immigrating illegally. We don’t in fact have the resources to do that, nor would we be willing to stomach the required violence. Conservative social policy is thus reborn in the form of a nudge, because that’s what restrictions look like in a violence-averse society.

An especially controversial conservative nudge is all the policy steps and regulatory restrictions and funding cuts that make it harder for women to get abortions. Many Americans must now travel a considerable distance to reach a qualified abortion provider, in some cases hundreds of miles. The cost is discouraging. And the greater inconvenience widens the gap of time between decision and final outcome, perhaps inducing some women to change their minds or simply let the plan go unfulfilled. Yet it is still possible to get an abortion, albeit with greater effort.

And:

I find it striking that nudge theorists usually market the idea using relatively “liberal” examples, such as improving public services. How much we view nudge as freedom-enhancing or as a sinister manipulation may depend on the context in which the nudge is placed. Neither conservatives nor liberals should be so quick to condemn or approve of nudge per se.

Do read the whole thing.

Markets in everything Victorian novels starring Baron Trump edition

Here is one bit of description:

In these books, the young German protagonist, Wilhelm Heinrich Sebastian Von Troomp, better known as Baron Trump, travels around and under the globe with his dog Bulger, meeting residents of as-of-yet undiscovered lands before arriving back home at Castle Trump. Trump is precocious, restless, and prone to get in trouble, with a brain so big that his head has grown to twice the normal size—a fact that, as we have seen, he mentions often. No one tells Trump that his belief that he looks great in traditional Chinese garb—his uniform for both volumes—is unwarranted.

Lockwood’s books are spring break meets Carmen Sandiego meets Jabberwocky; at the start of each story, Trump sets out eager to find new civilizations—and manages to get distracted by more than one lady along the way. One of the first places he visits in Travels and Adventures is the land of the toothless and nearly weightless Wind Eaters, who inflate to beach-ball size after a meal. They are generous hosts until Trump starts a fire. The intrigued Wind Eaters draw near, and promptly explode after the air they have ingested expands thanks to the flames. As Captain Go-Whizz, “a sort of leader among them,” chases the murderer, the dog Bulger bites one of the Wind Eaters until he deflates like a punctured balloon. The pair eventually escape, leaving the briefly betrothed Princess Pouf-fah without a mate, and Chief Ztwish-Ztwish and Queen Phew-yoo with many a funeral to plan.

Here is the full story.

Further assorted links

Nobel Prize awarded to Richard Thaler

This is a prize that is easy to understand. It is a prize for behavioral economics, for the ongoing importance of psychology in economic decision-making, and for “Nudge,” his famous and also bestselliing book co-authored with Cass Sunstein.

Here are previous MR posts on Thaler, we’ve already covered a great deal of his research. Here is Thaler on Twitter. Here is Thaler on scholar.google.com. Here is the Nobel press release, with a variety of excellent accompanying essays and materials. Here is Cass Sunstein’s overview of Thaler’s work.

Perhaps unknown to many, Thaler’s most heavily cited piece is on whether the stock market overreacts. He says yes this is possible for psychological reasons, and this article also uncovered some of the key evidence in favor of the now-vanquished “January effect” in stock returns, namely that for a while the market did very very well in the month of January. (Once discovered the effect went away.) Another excellent Thaler piece on finance is this one with Shleifer and Lee, on why closed end mutual funds sell at divergences from their true asset values. This too likely has something to do with market psychology and sentiment, as the same “asset package,” in two separate and non-arbitrageable markets, can sell for quite different prices, sometimes premia but usually discounts. This was one early and relative influential critique of the efficient markets hypothesis.

Another classic early Thaler piece is on a phenomenon known as “mental accounting,” for instance you might treat a dollar in your pocket as different from a dollar in your bank account. Or earned money may be treated different from money you just chanced upon, or won that morning in the stock market. This has significant implications for predicting consumer decisions concerning saving and spending; in particular, economists cannot simply measure income but must consider where the money came from and how it is perceived by consumers, namely how they are performing their mental accounting of the funds. Have you ever gone on a vacation with a notion that you would spend so much money, and then treated all expenditures within that range as essentially already decided? The initial piece on this topic was published in a marketing journal and it has funny terminology, a sign of how far from the mainstream this work once was. It is nonetheless a brilliant piece. Here is more Thaler on mental accounting.

Thaler, with Kahneman and Knetsch, was a major force behind discovering and measuring the so-called “endowment effect.” Once you have something, you value it much more! Maybe three or four times as much, possibly more than that. It makes policy evaluation difficult, because as economists we are not sure how much to privilege the status quo. Should we measure “willingness to pay” — what people are willing to pay for what they don’t already have? Or “willingness to be paid” — namely how eager people are to give up what they already possess? The latter magnitude will lead to much higher valuations for the assets in question. This by the way helps explain status quo bias in politics and other spheres of life. People value something much more highly once they view it as theirs.

This phenomenon also makes the Coase theorem tricky because the final allocation of resources may depend quite significantly on how the initial property rights are assigned, even when the initial wealth effect from such an allocation may appear to be quite small. See this Thaler piece with Knetsch. It’s not just that you assign property rights and let people trade, but rather how you assign the rights up front will create an endowment effect and thus significantly influence the final bargain that is struck.

With Jolls and Sunstein, here is Thaler on a behavioral approach to law and economics, a long survey but also constructive piece that became a major trend and has shaped law and economics for decades. He has done plenty and had a truly far-ranging impact, not just in one or two narrow fields.

Thaler’s “Nudge” idea, developed in conjunction with Cass Sunstein over the course of a major book and some articles, has led policymakers all over the world to focus on “choice architecture” in designing better systems, the UK even setting up a “Nudge Unit.” For instance, one way to encourage savings is to set up pension systems for employees so that the maximum contribution is the default, rather than an active choice people must make. This is sometimes referred to as a form of “soft” or “libertarian paternalism,” since choice is still present. Here is Thaler responding to some libertarian critiques of the nudge idea.

I first encountered Thaler’s work in graduate school, in the mid-1980s, in particular some of his pieces in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization; here is his early 1980 manifesto on how to think about consumer choice. I thought “this is great stuff,” and I gobbled it up, as it was pretty consistent with some of what I was imbibing from Thomas Schelling, in particular Thaler’s 1981 piece with Shefrin on the economics of self-control, a foundation for many later discussions of paternalism. I also thought “a shame this work isn’t going to become mainstream,” because at the time it wasn’t. It was seen as odd, under-demonstrated, and often it wasn’t in top journals. For some time Thaler taught at Cornell, a very good school but not a top top school of the kind where many Laureates might teach, such as Harvard or Chicago or MIT. Many people were surprised when finally he received an offer from the University of Chicago Business School, noting of course this was not the economics department. Obviously this Prize is a sign that Thaler truly has arrived at the very high levels of recognition, and I would note Thaler has been pegged as one of the favorites at least since 2010 or so. When Daniel Kahneman won some while ago and Thaler didn’t, many people thought “ah, that is it” because many of Thaler’s most famous pieces were written with Kahneman. Yet as time passed it became clear that Thaler’s work was holding up and spreading far and wide in influence, and he moved into a position of being a clear favorite to win.

Here is Thaler’s book on the making of behavioral economics. Excerpt:

…my thesis advisor, Sherwin Rosen, gave the following as an assessment of my career as a graduate student: “We did not expect much of him.”

Very lately Thaler on Twitter has been making some critical remarks about price gouging, suggesting we also must take into account what customers perceive as fair. Here is his earlier piece about fairness constraints on profit-seeking, still a classic.

Thaler has written many columns for The New York Times, here is one on boosting access to health care. Here are many more of them. Here is “Unless you are Spock, Irrelevant Things Matter for Investment Behavior.” Here is Thaler on making good citizenship fun. He also told us that trading up in the NFL draft isn’t worth it.

Thaler is underrated as a policy economist, here is an excellent NYT piece on the “public option” for health insurance, excerpt: “…instead of arguing about whether to have a public option, argue about the ground rules.”

His last pre-Nobel tweet was: “The @Expedia web site is using lots of #sludge. Advertised rates include cashing in of “points”, cancellation policies not salient if bad…”

A well-deserved prize and one that is relatively easy to explain, and most of Thaler’s works are easy to read even if you are not an economist. I would stress that Thaler has done more than even many of his fans may realize.

Richard Thaler Wins Nobel!

Richard Thaler wins the Nobel for behavioral economics! An excellent choice and one that makes my life easier because you probably already know his work. Indeed his work may already have influenced how much you save for retirement, how you pay your taxes and whether you will donate a kidney or not. In Britain, Thaler’s work was one of the inspirations for the Behavioral Insights Team which applies behavioral economics to public policy. Since being established in 2010 similar teams have been created around the world including in the United States.

Thaler’s intellectual biography Misbehaving (available free as kindle for Amazon Prime members is this a nudge?) is a fun guide to his work. Thaler will be the first to tell you he isn’t that smart. Relative to other Nobel prize winners that might even be true. None of his papers are technically difficult or excessively math heavy and most of his ideas are pretty obvious–obvious once you have heard them! Thaler cannot have been the first person in the world to notice that people like cashews but also like it when you take the cashews away to prevent them from eating more than they really want to eat (preferences Thaler noted at a dinner party of economists). But other people, especially economists, dismissed the evidence in front of their noses that people weren’t as rational as their theories suggested–People will be more careful with big decisions. Errors will cancel. Markets will take care of that–There were plenty of reasons to go back to pondering the beautiful austerity of theory. Thaler, however, especially after reading Kahneman and Tversky’s Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases realized that their could be a theory of misbehaving, a theory of irrational choice.

That theory is now called behavioral economics. It’s not as clean and straight as neo-classical theory. We still don’t know when one bias, of the many that have been documented, applies and when another applies. So much depends on context and what we bring to it that perhaps we never will. Nevertheless, there is no longer any question that some features of choice and the economy are better explained via systematic biases than by purely rational decision making.

In addition to Misbehaving and Nudge (the latter with Cass Sunstein who brought these ideas to law and government) you can find many of Thaler’s key ideas in the Anomalies column of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Probably this is the first economics Nobel to be given for a popular column! In many ways, however, these columns made Thaler’s reputation. The anomalies column was always a highlight of the issue and I remember discussing and debating these columns with Tyler and many others as they appeared. The same was true throughout the economics profession. Even economists like an anomaly.

One of the most important applications of behavioral economics has been to savings. Savings decisions are difficult because it’s not obvious how much to save or even how to save (bank accounts, mutual funds, Roth IRA, 401k etc. etc.). In addition, the decision can be administratively complex with annoying paperwork, and the benefits of good decision making don’t occur until decades into the future. Perhaps most importantly, we don’t receive clear and quick feedback about our choices. We don’t know whether we have saved too little or too much until it’s too late to change our decision. As a result, many of us fall back on defaults. These are the motivating ideas behind Thaler’s recommendations to set default rules such that people are automatically enrolled in pension plans that invest in low-cost market indices. Such default rules have changed saving behavior in the United States and around the world. Thaler’s Save More Tomorrow plans also ask people whether they want to plan today to save more of their raises, a simple yet profound change in default that makes it easier to save by lowering the perceived cost.

Thaler’s research is even changing football. His paper with Cade Massey, Overconfidence vs. Market Efficiency in the National Football League looked at “right to choose decisions” in the player draft. On the one hand, millions of dollars are made and lost on these decisions and they are being made repeatedly by professionals; thus, the case for rational decisions would seem to be strong. But on other hand, people are overconfident, they tend to make extreme forecasts, there is a winner’s curse, there is a false consensus effect (you think that everyone likes what you like), and there is present bias. These biases all suggest that decisions might be made poorly, even given the big stakes. Massey and Thaler find that it’s the latter.

Using archival data on draft-day trades, player performance and compensation, we compare the market value of draft picks with the historical value of drafted players. We find that top draft picks are overvalued in a manner that is inconsistent with rational expectations and efficient markets and consistent with psychological research.

Moreover, and this is the kicker, Massey and Thaler’s research has passed the market test! Bill Belichick started to pay attention first (econ undergrad natch) and now other smart teams are applying Thaler’s research to improve their choices.

Few economists have had more practical influence than Richard Thaler and behavioral economics is still on the upswing.