Month: September 2018

Sunday assorted links

1. U.S.-based renewable energy firms were not hurt by the election of Trump.

2. Commuting by bicycle in the U.S. is down since 2014. The post also considers why.

3. There are now more one hundred dollar bills than one dollar bills in the world.

4. Eighth-graders can in fact contribute to science (short video on listeria).

Chocolate markets in everything

You Can Rent This Cottage Made Entirely of Chocolate

Booking.com is making your Willy Wonka dreams come true with its new chocolate cottage (you read that right, chocolate) in Sèvres, France.

No, this isn’t simply a cottage filled with chocolate treats. Instead, it’s a cottage made entirely of the sweet stuff located at the glass house L’Orangerie Ephémère in the gardens of the Cité de la Céramique.

“Designed and manufactured by Jean-Luc Decluzeau, the renowned artisan chocolatier who specializes in chocolate sculptures, this unique, 18-square-meter chocolate cottage will be crafted out of approximately 1.5 tons of chocolate,” Booking.com shared in a statement.

Appealing to your identity in making a point

In a post which is interesting more generally, Arnold Kling makes this point:

I think Tyler missed the important difference between taking identity into account and having someone appeal to their identity. I agree with Bryan that the latter is a negative signal. Opening with “Speaking as a ____” is a bullying tactic.

Many have had a similar response, but I figured I would save up that point for an independent blog post, rather than putting it in the original. Here are a few relevant points:

1. If someone opens with “Speaking as a transgender latinx labor activist…”, or something similar, perhaps that is somewhat artless, but most likely it is relevant information to me, at least for most of the topics which correlate with that kind of introduction. I am happy enough with direct communication of that information, and don’t quite get what a GMU blogger would object to in that regard. Does the speaker have to wait until paragraph seven before obliquely hinting at being transgender? Communicate the information in Straussian fashion?

2. Being relatively established, most of the pieces I write already give such an introduction to me, for instance a column by-line or a back cover photo and author description on a book. Less established people face the burden of having to introduce themselves, and yes that is hard to do well, hard for any of us. You might rationally infer that these people are indeed less established, and possibly also less accomplished, but the introduction itself should be seen in this light, not as an outright negative. It is most of all a signal that the person is somewhat “at sea” in establishment institutions and their concomitant introductions, framings, and presentations. Yes, that outsider status possibly can be a negative signal in some regards, but a GMU blogger or independent scholar (as Arnold is) should not regard that as a negative signal per se. At the margin, I’d like to see people pay more attention to smart but non-mainstream sources.

3. For many audiences, I don’t need an introduction at all, nor would Bryan or Arnold. That’s great of course for us. But again we are being parasitic on other social forces having introduced us already. Let’s not pretend we’re above this whole game, we are not, we just have it much easier. EconLog itself has a click space for “Blogger Bios,” though right now it is empty, perhaps out of respect for Bryan’s views. Or how about if you get someone to blurb your books for you?

4. I’ve noticed that, for whatever reasons, women in today’s world often feel less comfortable putting themselves forward in public spaces. In most (not all) areas they blog at much lower rates, and they are also less willing to ask for a salary increase, among other manifestations of the phenomenon. Often, in this kind of situation, you also will find group members who “overshoot” the target and pursue a strategy which is the opposite of excess reticence. I won’t name names, but haven’t you heard something like “Speaking as a feminist, Dionysian, child of the 1960s, Freudian, Catholic, pro-sex, pagan, libertarian polymath…”? Maybe that is a mistake of style and presentation and even reasoning, but the deeper understanding is to figure out better means of evaluating people who “transact” in the public sphere at higher cost, not simply to dismiss or downgrade them.

5. If someone like Bill Gates were testifying in front of Congress and claimed “Speaking as the former CEO of a major company, I can attest that immigration is very important to the American economy” we wouldn’t really object very much, would we? Wouldn’t it seem entirely appropriate? So why do we so often hold similar moves against those further away from the establishment?

How about “as a Mongolian sheep herder, let me tell you what kinds of grass they like to eat…”?

Then why not “As a transgender activist…”? You don’t necessarily have to agree with what follows, just recognize they might know more than average about the topic.

To sum up, appealing to one’s identity possibly can be a negative signal. But overall it should be viewed not as a reason to dismiss such speakers and writers, but rather a chance to obtain a deeper understanding.

Vitalik Buterin and Glen Weyl dialog

The following is a series emails Vitalik Buterin and I [Glen] exchanged over the last day about RadicalxChange ideas. We thought the discussion might be useful to some as a) it covers a number of issues not discussed elsewhere that we consider important, b) it represents some of our latest thinking about these issues and c) it shows a bit of “the sausage being made” that some may find interesting. However, be aware that this is an internal communication and thus is at a pretty high level of specialization; there will be many parts that those not already well steeped in some combination of RadicalxChange ideas, economics, sociology, intellectual history, philosophy and cryptography may find hard to follow.

Here is the link. There are many excellent bits, here is one from Buterin:

Effect on centralization of physical power — one thing that scares me about more complex systems of property rights is that they would require more complex centralized infrastructure, including surveillance into people’s private activities, to be able to correctly enforce. Taxes already have this problem (you may recall Adam Smith believing that income taxes would be impossible because they would require an unacceptable level of intrusion into people’s private lives to enforce), and I wonder if the various proposals that we have for changing them would make things better or worse in this regard. I like Harberger taxes because they don’t require infrastructure to police whether or not undeclared transactions took place, though I worry in other cases, eg. your comment that your immigration proposal would require stronger enforcement of immigration rules, which realistically means stronger efforts to find and kick out people who overstay, which requires more surveillance of various kinds. All in all, I don’t think the radical markets ideas altogether fare that bad, but I guess my comment would be that non-panopticon-dependence should be an explicit desideratum to a greater degree than it is now.

Self-recommending…and which one of them do you think wrote this?:

The last couple of weeks talking to economists, sociologists and philosophers I have felt like they are hacking through a forest with pen knife and this perspective enables me to look from above (things still fuzzy) and have a crew of chainsaws at my command.

Unusual failed Beatle Asimov markets in everything

[Paul] McCartney was still wrestling with the comparison between the two bands [the Beatles and Wings]. A few months earlier he had commissioned veteran sci-fi author Isaac Asimov to write a screenplay. “He had the basic idea for the fantasy, which involved two sets of musical groups,” Asimov recalled, “a real one, and a group of extraterrestrial imposters. The real one would be in pursuit of the imposters and would eventually defeat them, despite the fact that the latter had supernormal powers.” Beyond that framework, McCartney offered Asimov nothing more than “a snatch of dialogue describing the moment when the group realised they were being victimised by imposters.” Asimov set to work and produced a screenplay that he called “suspenseful, realistic and moving.” But McCartney rejected it. As Asimov recalled, “He went back to his one scrap of dialogue out of which he apparently couldn’t move.”

That is from Peter Doggett’s excellent You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup.

Saturday assorted links

1. Ideology is the ultimate Augmented Reality.

2. All those complex Mayan cities!

3. “…greater variability is insufficient to explain male over-representation in STEM…the greatest difference in variability occurred in non-STEM subjects.”

4. “He’s reviewed more than 6,200 kinds of instant noodles.”

5. Another Emergent Ventures recipient.

6. James March has passed away.

7. Once again, democracy does cause/boost growth, ungated here.

Boring Speakers Drone On

It’s not just your imagination, boring speakers drone on. At least according to a small study reported in a letter to Nature:

I investigated this idea at a meeting where speakers were given 12-minute slots. I sat in on 50 talks for which I recorded the start and end time. I decided whether the talk was boring after 4 minutes, long before it became apparent whether the speaker would run overtime. The 34 interesting talks lasted, on average, a punctual 11 minutes and 42 seconds. The 16 boring ones dragged on for 13 minutes and 12 seconds (thereby wasting a statistically significant 1.5 min; t-test, t = 2.91, P = 0.007). For every 70 seconds that a speaker droned on, the odds that their talk had been boring doubled. For the audience, this is exciting news. Boring talks that seem interminable actually do go on for longer.

In my view, the fundamental explanation is that a boring speaker doesn’t think about their audience. A speaker who cares puts herself in the audience’s shoes, thinks in advance about what is important, how much an audience can absorb in one sitting, where a graphic would be helpful and so forth. A good speaker plans and practices and thus ends up being interesting and ending on time.

An email from Glen Weyl

I won’t do an extra indent, but this is all Glen, noting I added a link to the post of mine he referred to:

“Tyler, I hope all is well for you. I am writing to try to somewhat more coherently respond to our various exchanges, partly at the encouragement of Mark Lutter, whom I copy. As I understand it (but please correct me if I am wrong), you have two specific objections to the COST and QV and one general objection to the project of the book. If I have missed other things, please point me to them. Let me very briefly respond to these points:

- On the COST: you wrote (I cannot actually find the post at this point…not sure where it went) that human capital investments that are complementary with assets may be discouraged or otherwise prejudices by the COST. However, as we explain in the paper with Anthony (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2744810), it has been known since at least Rogerson’s paper (https://academic.oup.com/restud/article-abstract/59/4/777/1542650) that VCG leads to first-best investment, including in human capital, as long as those investments are privately valued; we show that this property extends to the COST. You seem to focus on examples in your post where those human capital investments are privately valued. I thus do not see an economic efficiency objection to the COST on these grounds.

- On QV: you write (https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/01/my-thoughts-on-quadratic-voting-and-politics-as-education.html) that democracy is about far more than decision-making; it is about what people learn and are induced to learn through the democratic process. This is a deep and critical point and central to what Sen has called the “constitutive” role of democracy. And this objection has been lodged not just by you but, for example, by Danielle Allen. It is one I greatly respect and have struggled with. A fundamental problem here is that no one to my knowledge has managed to model this information acquisition process in a formal model in a way that allows comparison across systems; I have tried, but things get very messy very quickly. Nonetheless, I have not been able to understand the informal arguments that suggest this would be systematically worse under QV and there are several suggestive arguments that it would be better. For example, under QV people have the ability to specialize in certain areas of issue or candidate expertise, which in turn should allow for deeper education and for advertising campaigns targeted at those who actually know and care about an issue, rather than those who are hardly paying attention. Perhaps some would argue that this is a bug, not a feature, because we want every citizen to be informed about every issue; but this seems to be as implausible as suggesting that the division of labor degrades our ability to perform a variety of household tasks. For more on these, Eric and I have written several articles that discuss: https://www.vanderbiltlawreview.org/2015/03/voting-squared-quadratic-voting-in-democratic-politics/ [and] https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/public-choice-1-2-2017/12454020.

- There is a broader Burkean argument that you seem to be making, namely that these institutions are extremely different than those we have historically used and may well have very bad, unintended consequences. Here, I don’t think we disagree, but I think nonetheless there are at least two reasons I don’t see this as greatly diminishing the value of the ideas. First, all novel improvements, whether to technology or social institutions, must confront this objection. And they should confront it, I think, by experimenting at small scales and gradually scaling up and/or course-correcting as we learn about them. The questions are then a) does the innovation have enough promise to be worth experimenting with, b) is it so risky to experiment with at small scales even that this vitiates a) and c) does it seem like these experiments will teach us something about broader scale applicability. It seems to me that designs that so clearly address failures that economic theory we both accept says are very large, that are not just worked out in a narrow model but that we have studied from a range of not just economic but sociological and philosophical perspectives and which have caught the imagination of a broad set of entrepreneurs, activists and artists who are really interested in such experiments satisfies a). I don’t see any objections you or others have raised as raising significant concerns on b). And on c), it seems to me we will learn quite a lot from even relatively modest experiments (and already have) about the objections I hear most frequently (such as those related to collusion for QV or instability for the COST) that at very least will allow us to incrementally improve and scale a bit larger. So, it seems to me, the strong interest in experimenting with these ideas should be encouraged.

Finally, it seems to me that even if you remain convinced that there are unsurmountable practical difficulties with these mechanisms, that they play an important role in illustrating some pretty sharp divergences between what basic allocative efficiency calls for (and what the marginal revolutionaries like Jevons and Walras were quite explicit about their theories implying) and the outcomes we would expect to arise in the classic libertarian world. I think the liberal radicalism mechanism makes this sharpest. This seems instructive even if there is no way to remedy the limitations in these mechanisms because it suggests that the ideal toward which we should be steering societies using mechanisms that are not so dangerous are quite different than the ideal envisioned in standard libertarian theory. For example, the ideal would seem to involve a much greater role for a range of collective organizations at different community scales with some ability to receive tax-based support than standard libertarian theory would allow.

I am interested in your thoughts on these matters and continuing the exchange. Sorry for the length of this email, but I felt that I owed you a single, coherent and fairly detailed response.”

TC again: For further detail, I refer you to Glen’s book with Eric Posner. For background, here are my earlier posts on their work.

Friday more assorted links

2. “…we reexamine one of the largest partisan shifts in a modern democracy: Southern whites’ exodus from the Democratic Party. We show that defection among racially conservative whites explains the entire decline from 1958 to 1980.” Income seems to play essentially no role.

3. Eric Chyn: “I study public housing demolitions in Chicago, which forced low-income households to relocate to less disadvantaged neighborhoods using housing vouchers. Specifically, I compare young adult outcomes of displaced children to their peers who lived in nearby public housing that was not demolished. Displaced children are more likely to be employed and earn more in young adulthood. I also find that displaced children have fewer violent crime arrests. Children displaced at young ages have lower high school dropout rates.”

4. The book The Spirit Level does not hold up to scrutiny.

5. Paul Romer on the gender gap.

6. MMT profile.

Friday assorted links

1. Robert Wiblin podcast with Daniel Ellsberg on matters nuclear.

2. What are the economic costs of physical contact in high school and college male sports?

3. Terms used in the military.

4. “Tomorrow, we’re opening Amazon 4-star, a new physical store where everything for sale is rated 4 stars and above, is a top seller, or is new and trending on Amazon.com.” Link here.

5. “I’m honored to accept a grant from @tylercowen‘s Emergent Venture’s to create a genealogy of street art, using machine learning.” Link here. Here is another winner: “…for my projects on brain-computer interfaces & learning!”

Which countries have the most human capital?

Here is a new Lancet paper by Stephen S. Lim, et.al., via the excellent Charles Klingman. Finland is first, the United States is #27, and China and Russia are #44 and #49 respectively. There is plenty of “rigor” in the paper, but I say this is a good example of what is wrong with the social sciences and more specifically the publication process. The correct answer is a weighted average of the median, the average, the high peaks, and a country’s ability to innovate, part of which depends upon the market size a person has in his or her sights. So in reality the United States is number one, and China and Russia should both rank much higher (Cuba and Brunei beat them out, for instance, Cuba at #41, Brunei at #29). And does it really make sense to put North Korea (#113) between Ecuador and Egypt? I’m fine with Finland being in the top fifteen, but I am not even sure it beats Sweden. Overall the paper would do better by simply measuring non-natural resource-based per capita gdp, though of course that could be improved upon too.

Now, I did zero work on that one, and came up with a better result than the authors. What does that tell you?

Addendum: You will note the first sentence of the paper’s background claims: human capital refers to “the level of education and health in a population”. The first two sentences of the actual paper immediately contradict this: “Human capital refers to the attributes of a population that, along with physical capital such as buildings, equipment, and other tangible assets, contribute to economic productivity. Human capital is characterised as the aggregate levels of education, training, skills, and health in a population, affecting the rate at which technologies can be developed, adopted, and employed to increase productivity.” The paper does an OK job of measuring the former, but absolutely fails on the latter.

How should we judge appeals to identity

Bryan Caplan wrote this in his description of GMU blogger culture:

Appealing to your identity is a reason to discount what you say, not a reason to pay extra attention.

Bryan explains more, not easy for me to summarize but do read his full account. Let me instead try to state my own views:

1. If someone makes a claim new or foreign to you, and that person comes from a different background in some manner, you probably should up the amount of attention you give that claim because the person is from a different background. Your marginal need to learn from that person is probably above-average, noting of course this can be countermanded by other signals. That said, I recognize that our ability to learn from “different others” may be below average, given the possible absence of a common conceptual framework. Nonetheless, I say be ambitious in your learning!

2. If someone makes a claim you already disagree with, and that person comes from a different background in some manner, you should try to figure out why that person might see the matter differently. You should try harder, at the margin, precisely because the person is from a different background. Again, this follows from a mix of marginalism and Bayesian reasoning and ambition in learning.

3. When you hear a person from a different background, try not to get too caught up in the “identity politics” of it, either positively or negatively. Try to steer your thoughts to: “People from this background in fact have a wide diversity of views on this topic. Still, I will try to learn from this person’s different background.” Try not to think: “This is how group X feels about issue Y.”

4. I’ve already noted that you often learn more efficiently from people who come from similar backgrounds as yourself. Even putting language aside, I am more likely to have a fruitful career-enhancing dialogue with another nerdy economist than with a Mongolian sheep-herder. In this regard I worry when I hear an uncritical celebration of intellectual diversity for its own sake. To me it too often sounds like mere mood affiliation, subservient to political ends and devoid of cognitive content.

But still, I do not wish to rebel against such sentiments too much. At the end of the day I am left with my intellectual ambition and I really do wish to go visit Mongolia, including for the sheep herders. And to the extent I am informed in some ways that maybe not all of my peers are, the intellectual ambition I am presenting here is a big reason why. I seek to encourage more such ambition, rather than to give people reasons for evading it.

*The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the revolution that made computing personal*

By M. Mitchell Waldrop. Not only is the content essential, but it is one of the most beautiful books, as a physical object, I have seen in years. From Stripe Press.

Mihail Sebastian, *Journal 1935-1944*

I am surprised this work is not better known. A literary diary of a Romanian Jew, it captures the beauties of European high culture during the pre-war thirties, most of all classical music and early 20th century literature, but also the only slighter later descent into madness. It’s his friends and fellow intellectuals who turn on him the most. I don’t know a better source for capturing the sense of surprise and then foreboding that people must have felt as Hitler racked up one victory after another.

In late 1944, after the course of the war had reversed, Sebastian wrote:

I am not willing to be disappointed. I don’t accept that I have any such right. The Germans and Hitlerism have croaked. That’s enough.

I always knew deep down that I’d happily have died to bring Germany’s collapse a fraction of an inch closer. Germany has collapsed — and I am alive. What more can I ask? So many have died without seeing the beast perish with their own eyes! We who remain alive have had that immense good fortune.

Miraculously, Sebastian survived the Holocaust and was never deported to the camps. On 29 May 1945, however, he was hit and killed by a truck in downtown Bucharest, while walking on his way to teach class.

You can buy the work here, and I’ve since ordered one of Sebastian’s novels. Here is a NYT review.

The Liberal Radicalism Mechanism for Producing Public Goods

The mechanism for producing public goods in Buterin, Hitzig, and Weyl’s, Liberal Radicalism is quite amazing and a quantum leap in public-goods mechanism-design not seen since the Vickrey-Clarke-Groves mechanism of the 1970s. In this post, I want to illustrate the mechanism using a very simple example. Let’s imagine that there are two individuals and a public good available in quantity, g. The two individuals value the public good according to U1(g)=70 g – (g^2)/2 and U2(g)=40 g – g^2. Those utility functions mean that the public good has diminishing utility for each individual as shown by the figure at right. The public good can be produced at MC=80.

The mechanism for producing public goods in Buterin, Hitzig, and Weyl’s, Liberal Radicalism is quite amazing and a quantum leap in public-goods mechanism-design not seen since the Vickrey-Clarke-Groves mechanism of the 1970s. In this post, I want to illustrate the mechanism using a very simple example. Let’s imagine that there are two individuals and a public good available in quantity, g. The two individuals value the public good according to U1(g)=70 g – (g^2)/2 and U2(g)=40 g – g^2. Those utility functions mean that the public good has diminishing utility for each individual as shown by the figure at right. The public good can be produced at MC=80.

Now let’s solve for the private and socially optimal public good provision in the ordinary way. For the private optimum each  individual will want to set the MB of contributing to g equal to the marginal cost. Taking the derivative of the utility functions we get MB1=70-g and MB2= 40 – 2g (users of Syverson, Levitt & Goolsbee may recognize this public good problem). Notice that for both individuals, MB<MC, so without coordination, private provision doesn’t even get off the ground.

individual will want to set the MB of contributing to g equal to the marginal cost. Taking the derivative of the utility functions we get MB1=70-g and MB2= 40 – 2g (users of Syverson, Levitt & Goolsbee may recognize this public good problem). Notice that for both individuals, MB<MC, so without coordination, private provision doesn’t even get off the ground.

What’s the socially optimal level of provision? Since g is a public good we sum the two marginal benefit curves and set the sum equal to the MC, namely 110 – 3 g = 80 which solves to g=10. The situation is illustrated in the figure at left.

We were able to compute the optimum level of the public good because we knew each individual’s utility function. In the real world each individual’s utility function is private information. Thus, to reach the social optimum we must solve two problems. The information problem and the free rider problem. The information problem is that no one knows the optimal quantity of the public good. The free rider problem is that no one is willing to pay for the public good. These two problems are related but they are not the same. My Dominant Assurance Contract, for example, works on solving the free rider problem assuming we know the optimal quantity of the public good (e.g. we can usually calculate how big a bridge or dam we need.) The LR mechanism in contrast solves the information problem but it requires that a third party such as the government or a private benefactor “tops up” private contributions in a special way.

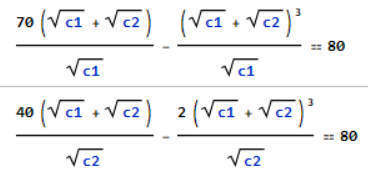

The topping up function is the key to the LR mechanism. In this two person, one public good example the topping up function is:

Where c1 is the amount that individual one chooses to contribute to the public good and c2 is the amount that individual two chooses to contribute to the public good. In other words, the public benefactor says “you decide how much to contribute and I will top up to amount g” (it can be shown that (g>c1+c2)).

Where c1 is the amount that individual one chooses to contribute to the public good and c2 is the amount that individual two chooses to contribute to the public good. In other words, the public benefactor says “you decide how much to contribute and I will top up to amount g” (it can be shown that (g>c1+c2)).

Now let’s solve for the private optimum using the mechanism. To do so return to the utility functions U1(g)=70 g – (g^2)/2 and U2(g)=40 g – g^2 but substitute for g with the topping up function and then take the derivative of U1 with respect to c1 and set equal to the marginal cost of the public good and similarly for U2. Notice that we are implicitly assuming that the government can use lump sum taxation to fund any difference between g and c1+c2 or that projects are fairly small with respect to total government funding so that it makes sense for individuals to ignore any effect of their choices on the benefactor’s purse–these assumptions seem fairly innocuous–Buterin, Hitzig, and Weyl discuss at greater length.

Notice that we are solving for the optimal contributions to the public good exactly as before–each individual is maximizing their own selfish utility–only now taking into account the top-up function. Taking the derivatives and setting equal to the MC produces two equations with two unknowns which we need to solve simultaneously:

These equations are solved at c1== 45/8 and c2== 5/8. Recall that the privately optimal contributions without the top-up function were 0 and 0 so we have certainly improved over that. But wait, there’s more! How much g is produced when the contribution levels are c1== 45/8 and c2== 5/8? Substituting these values for c1 and c2 into the top-up function we find that g=10, the socially optimal amount!

In equilibrium, individual 1 contributes 45/8 to the public good, individual 2 contributes 5/8 and the remainder,15/4, is contributed by the government. But recall that the government had no idea going in what the optimal amount of the public good was. The government used the contribution levels under the top-up mechanism as a signal to decide how much of the public good to produce and almost magically the top-up function is such that citizens will voluntarily contribute exactly the amount that correctly signals how much society as a whole values the public good. Amazing!

Naturally there are a few issues. The optimal solution is a Nash equilibrium which may not be easy to find as everyone must take into account everyone else’s actions to reach equilibrium (an iterative process may help). The mechanism is also potentially vulnerable to collusion. We need to test this mechanism in the lab and in the field. Nevertheless, this is a notable contribution to the theory of public goods and to applied mechanism design.

Hat tip: Discussion with Tyler, Robin, Andrew, Ank and Garett Jones who also has notes on the mechanism.