Assorted links

2. New critique of Woodford and ngdp targeting, from Gavyn Davies and others.

3. Fish fraud, and excellent material on Iranian hyperinflation.

4. Some of the maple syrup is seized, and the policy uncertainty costs of horse nationalism.

5. There is no great stagnation (the ostrich pillow), and Thiel and Kasparov and Rogoff and Shuttleworth will debate.

Social Networks and Risk of Homicide Victimization in an African American Community

That is a new paper from Andrew V. Papachristos and Christopher Wildeman, here is the abstract:

This study estimates the association of an individual’s position in a social network with their risk of homicide victimization across a high crime African American community in Chicago. Data are drawn from five years of arrest and victimization incidents from the Chicago Police Department. Results indicate that the risk of homicide is highly concentrated within the study community: 41 percent of all gun homicides in the study community occurred within a social network containing less than 4 percent of the neighborhood’s population. Logistic regression models demonstrate that network-level indicators reduce the association between individual-level risk factors and the risk of homicide victimization, as well as improve overall prediction of individual victimization. In particular, social distance to a homicide victim is negatively and strongly associated with individual victimization: each social tie removed from a homicide victim decreases one’s odds of being a homicide victim by approximately 57 percent. Findings suggest that understanding the social networks of offenders can allow researchers to more precisely predict individual homicide victimization within high crime communities.

Some of those sentences could be framed for their importance. For the pointer I thank DP.

Here are other papers by Andrew Papachristos. Here is a paper by Christopher Wildeman.

The new Fable of the Bees literature

From the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, there is a new paper by Randal R. Rucker, Walter N. Thurman, and Michael Burgett (Dept. of Entomology), here is the abstract:

The world’s most extensive markets for pollination services are those for honey bee pollination in the United States. These markets play important roles in coordinating the behavior of migratory beekeepers, who both produce honey and provide substitutes for ecosystem pollination services. We analyze the economic forces that drive migratory beekeeping and theoretically and empirically analyze the determinants of pollination fees in a larger and richer data set than has been studied before. Our empirical results expand our understanding of pollination markets and market-supporting institutions that internalize external effects.

This is a deep and thoughtful analysis which extends the tradition of Steven Cheung. There is an earlier ungated version here. Here is a related paper from UC Davis, and here is a related paper on the economics of honeybee pollination in Georgia. Here is a very good summary of the main piece.

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Emails I receive (the consumer surplus of the internet)

…the origins of your name, off by a letter.

RL

> Put the following text into google: freemason Cowan Tyler What is the result?

Interesting. “Tyler” is the title of an officer in the Masonic hierarchy, while a “cowan” is a stonemason who is not a member of the Freemasons guild. This from “Freemasonry for Dummies”:

The Tyler’s job is to keep off all “cowans and eavesdroppers” (for more on the Tyler, see Chapter 5). The term cowan is unusual and its origin is probably from a very old Anglo-Saxon word meaning “dog.” Cowan came to be a Scottish word used as a putdown to describe stonemasons who did not join the Freemasons guild, while the English used it to describe Masons who built rough stone walls without mortar and did not know the true secrets of Freemasonry.

Assorted links

Natural Products Association opposes California GMO labelling proposition

Read their reasons here.

For the pointer I thank Mark Thorson.

What kind of austerity did Great Britain implement in the 1920s?

When it comes to the post-WWI period, Paul Krugman recently argued: “…Britain demonstrated a fairly awesome commitment to austerity…” (and see here today’s post).

The cited IMF report notes with disapproval:

…the U.K. government implemented a policy mix of severe fiscal austerity and tight monetary policy. The primary surplus was kept near 7 percent of GDP throughout the 1920s. This was accomplished through large expenditure decreases, courtesy of the “Geddes axe,” and a continuation of the higher tax levels introduced during the war.

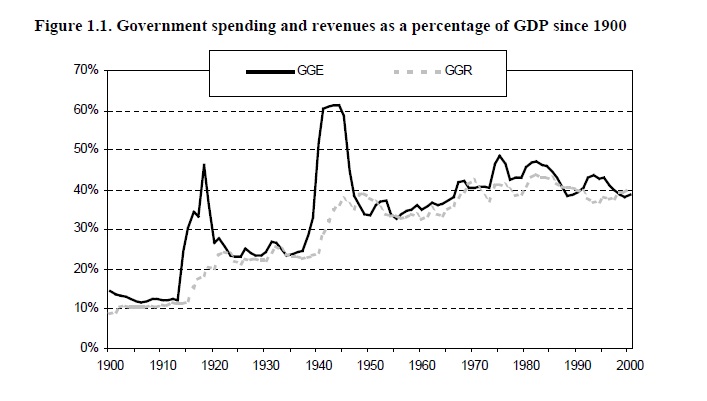

Is this portrait true? I say yes and no. For 1918-1920, government spending plummets, mostly because of demobilization and the end of the war, source here.

Yet there is an alternative perspective. Even after the demobilization is over, consider that in 1910 British government spending was about 10% of gdp and in the 1920s it runs near 25% of gdp. Is that such an awesome commitment to austerity?

If we consider a more finely grained approach, and focus on shorter-term rates of change, we do see real restraint on the spending side:

…spending was cut by 10% in real terms in two years, while tax as a share of GDP remained constant. The budget deficit was reduced from 7% GDP in 1920 to near balance in 1923, followed by a swift recovery. Defence bore the brunt of the cuts.

As mentioned in the quotation (“followed by a swift recovery”), this transition went reasonably well. If you read this very up to date, very careful with the data paper (try p.10), you see a notable gdp plunge from 1920-1921, mostly from a coal strike and a series of postwar shocks, and then solid growth from 1921 to 1926, running over and after the period when Britain was cutting government spending. It seems that policy was hardly a macroeconomic catastrophe. Things do go south in 1926, but it is well known that is from bad monetary and exchange rate policy, plus a major coal strike.

Or read Barry Eichengreen (pdf). He notes that Britain under-performs relative to other European nations in the first half of the 1920s, although he focuses much more on monetary policy and real factors, rather than fiscal policy. Furthermore, that’s hardly the only period when Britain was under-performing its rivals on the continent.

In other words, I don’t see how the episode as a whole supports the interpretative weight being placed upon it as an anti-austerity parable. Note that when it comes to the U.S. (switching from the UK for a moment), Krugman wrote the entirely defensible sentence: “…even a cursory examination of the available data suggests that 1921 has few useful lessons for the kind of slump we’re facing now.” If the UK in 1921 shows more relevance, that has yet to be shown.

In which they fail to credit Miss A. Elk

“Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks”

The necks of the sauropod dinosaurs reached 15 m in length: six times longer than that of the world record giraffe and five times longer than those of all other terrestrial animals. Several anatomical features enabled this extreme elongation, including: absolutely large body size and quadrupedal stance providing a stable platform for a long neck; a small, light head that did not orally process food; cervical vertebrae that were both numerous and individually elongate; an efficient air-sac-based respiratory system; and distinctive cervical architecture. Relevant features of sauropod cervical vertebrae include: pneumatic chambers that enabled the bone to be positioned in a mechanically efficient way within the envelope; and muscular attachments of varying importance to the neural spines, epipophyses and cervical ribs. Other long-necked tetrapods lacked important features of sauropods, preventing the evolution of longer necks: for example, giraffes have relatively small torsos and large, heavy heads, share the usual mammalian constraint of only seven cervical vertebrae, and lack an air-sac system and pneumatic bones. Among non-sauropods, their saurischian relatives the theropod dinosaurs seem to have been best placed to evolve long necks, and indeed they probably surpassed those of giraffes. But 150 million years of evolution did not suffice for them to exceed a relatively modest 2.5 m.

The link is here, and for the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson. The inspiration for this paper can be found here.

The political business cycle in Honduras

In Honduras, one of Latin America’s poorest countries and also its most dangerous, candidates dole out another kind of political swag: coffins for the destitute.

Charities organized by politicians scour poor neighborhoods in search of families of murder victims who cannot afford funeral services or even a simple casket to bury their beloved. There are plenty of takers in this Central American country, where two out of three workers earn less than the minimum wage of $300 a month, and more than 136 people are killed every week.

Here is more, courtesy of Daniel Lippman; here is Daniel’s piece on Medicaid cuts for dental services.

*Information Wants to be Shared*

That is the new Harvard Business Review Press book by Joshua Gans, Amazon link here, $3.99, recommended. Here is Joshua’s blog.

Questions that are rarely asked

It is estimated that less than $1B is spent in the U.S. each year on education research, with the federal government spending about $700M and universities, foundations and the private sector spending about $300M. That may sound like a lot, but it’s not. Consider that medicine and education should be two sides of the same coin. Both are services that developed democracies have decided all citizens are entitled to regardless of birth, station or resources. Medicine advances human health and happiness. Education advances economic productivity and happiness. Then consider that $140B is spent in the U.S. each year on medical research.

How to explain the 140:1 ratio?

Here is more.

Assorted links

1. Three frank questions about your research.

2. NYU Stern School now has some class macro materials on-line, and some short Jeff Ely videos on microeconomics.

3. The backlash against foodies, and the Swiss are at the Ricardian margin with cows. No SMS in Romansch? But is it art?

4. The new approach of Jeffrey Sachs and the UN to sustainable development.

5. Pakistan in the past, with photos.

6. My earlier post on how to improve the Presidential debates.

Baumol’s new book on the cost disease

It is self-recommending, here are a few points of relevance:

1. There has been a clear cost disease in most kinds of education and many kinds of medicine, but I blame institutions and laws as much as the intrinsic nature of the product.

2. I do not see the arts as subject to the cost disease very much at all. As for the “live performing arts,” the disease seems to afflict the older and less innovative sectors, such as opera and the symphony. There is plenty of live music these days, it is offered in innovative ways, and much of it is free.

3. Even “the live performing arts” can be broken down into underlying characteristics, many of which show a great deal of recent innovation. For instance the supply of “musical immediacy” has been non-stagnant through YouTube, which often gives you a better glimpse of the performer than you get through nosebleed seats and giant screens. YouTube isn’t “live,” but there is no particular reason to break down the analysis at that level and certainly it is not a sacred category for consumers.

4. In many sectors of the arts, especially music, consumers demand constant turnover of product. Old music becomes “obsolete” — for whatever sociological reasons — and in this sense the sector is creating lots of new value every year. From an “objectivist” point of view they are still strumming guitars with the same speed, but from a subjectivist point of view — the relevant one for the economist – they are remarkably innovative all the time in the battle against obsolescence. A lot of the cost disease argument is actually an aesthetic objection that the art forms which have already peaked — such as Mozart — sometimes have a hard time holding their ground in terms of cost and innovation.

5. In general “cost disease” sectors do not remain constant over time. Agriculture has been unusually stagnant for the last twenty or so years, but it is hardly obvious that this trend will continue for the next century to come and it certainly was not the case for the period 1948-1990, quite the contrary.

6. The stagnancy of one sector may depend on the stagnancy of other sectors in non-transparent ways. “Live music” may seem like it doesn’t change much, but lifting the embargo on Cuba would boost the quantity and quality of my consumption of spectacular concert experiences, as would a non-stop flight to Haiti.

You can buy the book here.

Addendum: Matt Yglesias comments.

*Mismatch*

The authors are Richard H. Sander and Stuart Taylor, Jr., and the subtitle is How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It.

Here is the book’s website, and a summary:

… law professor Richard Sander and journalist Stuart Taylor, Jr. draw on extensive new research to prove that racial preferences put many students in educational settings where they have no hope of succeeding. Because they’re under-prepared, fewer than half of black affirmative action beneficiaries in American law schools pass their bar exams. Preferences for well-off minorities help shut out poorer students of all races. More troubling still, major universities, fearing a backlash, refuse to confront the clear evidence of affirmative action’s failure.

As you may know, the Supreme Court starts hearing oral arguments on affirmative action on October 9th. I have not much followed the empirical debate on affirmative action, but it seems to me this is likely the best recent book on the “anti” side. On the pro side, you can read The Shape of the River, by William Bowen and Derek Bok.

Crowdsourcing the lowest fare

Travelers with complex travel plans may have noticed, however, that the search results aren’t necessarily consistent. This has created a business opportunity for Flightfox, a start-up company based in Mountain View, Calif., which uses a contest format to come up with the best fare that the crowd — all Flightfox-approved users — can find.

A traveler goes to Flightfox.com and sets up a competition, supplying information about the desired itinerary and clarifying a few preferences, like a willingness to “fly on any airline to save money” or a tolerance of “long layovers to save money.” Once Flightfox posts the contest, the crowd is invited to go to work and submit fares.

The contest runs three days, and the winner, the person who finds the lowest fare, gets 75 percent of the finder’s fee that the traveler pays Flightfox when setting up the competition. Flightfox says fees depend on the complexity of the itinerary; many current contests have fees in the $34-to-$59 range.

Here is more, and for the pointer I thank @ArikSharon.