Category: Current Affairs

Why is Obamacare still unpopular?

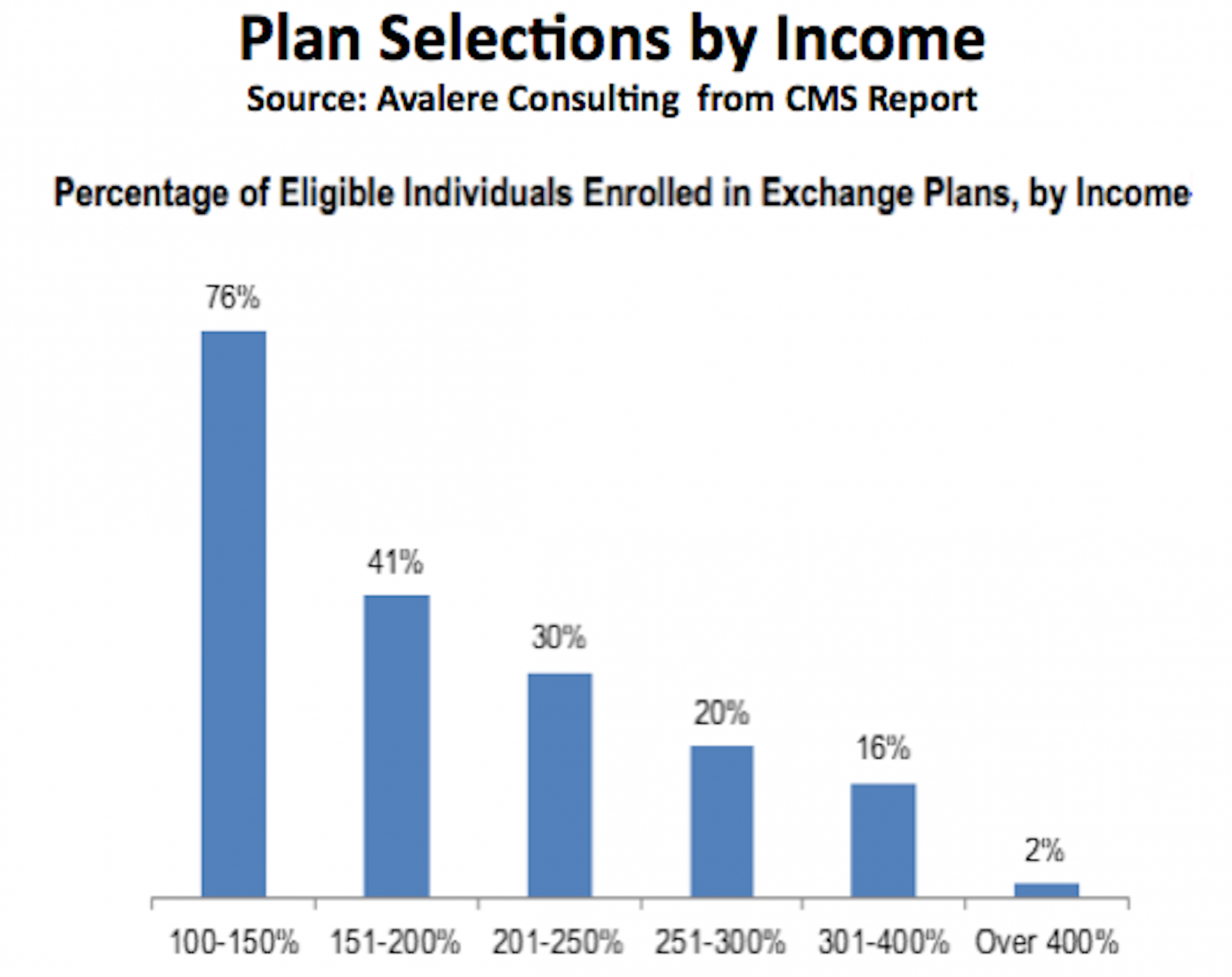

After all of this and two complete open enrollments, only 40% of those who are eligible for Obamacare have signed up—far below the proportion of the market insurers have historically needed to assure a sustainable risk pool.

If this were a private enterprise enjoying these kinds of benefits [ namely legal coercion], and only sold its product to 40% of the market, its CEO would be fired.

Looking at this picture, only 20% of those eligible for Obamacare, who make between 251% and 300% of the poverty level, bought Obamacare. Why?

The Obama administration will in fact be increasing the subsidies it will pay to insurance companies.

The legal problem with the blockchain

“The law will not treat a ledger record as authoritative if everyone knows that the current longest chain contains blocks generated by an anonymous attacker who replaced a bit of history that was chronologically prior,” he says. “In financial markets there’s always a mechanism to correct an attack. In a blockchain there is no mechanism to correct it — people have to accept it.”

That is an FT quotation from Robert Sams, the article is interesting more generally, focusing on Wall Street’s attempt to incorporate the blockchain in settlement in some manner.

The Battle for Greece

The Greek story is being framed as a battle between the Greeks and the Germans and thus between spending and austerity. But this frame can’t make sense of the fact that, win or lose, large numbers of Greeks will vote for austerity on Sunday.

To understand what’s really going on, listen to this remarkable interview between NPR’s Robin Young and Nikolalos Voglis, a restaurant owner in Athens. The interview begins with a discussion of the crisis. No one has cash or credit and Voglis’s restaurant is basically shuttered. Young then asks Voglis how he will vote on Sunday and he replies, “Definitely, Yes.” Young is surprised, she tries to clarify, you will vote, “even for more austerity?” “That’s right,” he replies.

Following the conventional frame, Young finds this difficult to understand and she pushes back against Voglis with all the conventional arguments. She quotes Paul Krugman saying that the problem isn’t really Greece’s doing, that the IMF and EU are being too tough on Greece, that Greece has done a lot of cutting already and so on. Voglis responds:

We are on the right track but unfortunately the job wasn’t completed. We are a country in the European Community which has the biggest public sector in Europe. And all of us in the private sector spend millions to support the situation. So the only way that Greece can become a true Western country…is to make these reforms.

…Look the main problem in this country is the public sector. There is no other problem. Entrepreneurs here are very, very competitive. We have to let this thing, this monster that we call the public sector, it has to go, it has to finish. This is the main issue.

Many Greeks are sick and tired of the bloated public sector and its corruption, inefficiency and waste. In this frame, the Greek story is not fundamentally about Greeks versus Germans it’s about the Greek people versus their government–the Germans have simply been the vehicle that has brought the Greeks to their kairotic moment. The Greeks want normalcy, as the Poles did after communism. If the Yes vote wins on Sunday it will be the Greeks voting not just against the current administration but against the entire state apparatus.

Fear the multiple marginalization

Upcoming Conversations with Tyler

The next three will be with Luigi Zingales, Dani Rodrik, and Clifford Asness, you will find the details here, all coming this fall!

China and the high cost of hiring labor

…[recent developments] may well mark the beginning of an important longer-term shift in China’s labor market and policies: the State Council lowered employers’ required contributions to two social insurance programs, injury and maternity insurance, a move it said would save firms 27 billion renminbi a year (see the China Labour Bulletin for an English-language summary). Yes, I know this sounds boring and technical, so why is it important? Because it starts to address one of the biggest but least-known issues in China’s job market: the very high costs employers face to hire workers.

It is not a very well-known fact that China has some of the toughest labor regulations in the world, and some of the highest required contribution rates to social insurance programs. As a result, the “labor wedge”–the percentage of the total cost of an employee that comes from things other than wages–in China is around 45%, as high as in a number of European countries (this is according to an estimate by John Giles in a World Bank paper;…

This fact does not square with the widespread perception of China as a nation of sweatshops employing hordes of migrant workers, and indeed is a relatively recent development stemming from the 2008 Labor Contract Law. But China’s problem with these generous worker protections is ultimately the same one that many other developing countries have encountered: strong legal protections and generous insurance programs are so expensive that in practice they only become available to part of the workforce. Effectively China has two labor markets: one for urban white-collar jobs with all the legal protections, and one for blue-collar jobs held by rural migrant workers that generally lack the full set of benefits.

That is yet another neglected China story…

The view from Vilnius, part II

When Greece’s finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, in an early round of negotiations in Brussels, complained that Greek pensions could not be cut any further, he was reminded bluntly by his colleague from Lithuania that pensioners there have survived on far less. Lithuania, according to the most recent figures issued by Eurostat, the European statistics agency, spends 472 euros, about $598, per capita on pensions, less than a third of the 1,625 euros spent by Greece. Bulgaria spends just 257 euros. This data refers to 2012 and Greek pensions have since been cut, but they still remain higher than those in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Croatia and nearly all other states in eastern, central and southeastern Europe.

There is more from Andrew Higgins in the NYT here.

Planetary Defense is a Public Good

Today is Asteroid Day, the anniversary of the largest asteroid impact in recent history, the June 30, 1908 Siberian Tunguska asteroid strike. The Tunguska asteroid was only about 40 meters in size but the impact was 1000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima nuclear bomb.

Large asteroid strikes are low-probability, high-death events–so high-death that by some estimates the probability of dying from an asteroid strike is on the same order as dying in an airplane crash. To mark asteroid day, events around the world, including here at the observatory at George Mason University, will discuss asteroids and how we can protect our civilization.

Tyler and I are signatories to the 100X Declaration which reads in part:

There are a million asteroids in our solar system that have the potential to strike Earth and destroy a city, yet we have discovered less than 10,000….

Therefore, we, the undersigned, call for…A rapid hundred-fold acceleration of the discovery and tracking of Near-Earth Asteroids to 100,000 per year within the next ten years.

I am also a contributor to an Indiegogo campaign to develop a planetary defense system–yes, seriously! I don’t expect the campaign to succeed because, as our principles of economics textbook explains, too many people will try to free ride. But perhaps the campaign will generate some needed attention. In the meantime, check out this video on public goods and asteroid defense from our MRU course (as always the videos are free for anyone to use in the classroom.)

By the way, can you identify the easter egg to growing up in the 1980s?

The Anne Krueger report on Puerto Rico

You’ll find it here (PDF), co-authored with Ranjit Teja and Andrew Wolfe. Here is a bit of the introductory summary:

Structural reforms

Restoring growth requires restoring competitiveness. Key here is local and federal action to lower labor costs gradually and encourage employment (minimum wage, labor laws, and welfare reform), and to cut the very high cost of electricity and transportation (Jones Act). Local laws that raise input costs should be liberalized and obstacles to the ease of doing business removed. Public enterprise reform is also crucial.

Fiscal reform and public debt.

Probably the most startling finding in this report will be that the true fiscal deficit is much larger than assumed. Even a major fiscal effort leaves residual financing gaps in coming years, which can be bridged by debt restructuring (a voluntary exchange of existing bonds for new ones with a longer/lower debt service profile). Public enterprises too face financial challenges and are in discussions with their creditors. Despite legal complexities, all discussions with creditors should be coordinated.

Institutional credibility.

The legacy of weak budget execution and opaque data – our fiscal analysis entailed many iterations – must be overcome. Priorities include legislative approval of a multi-year fiscal adjustment plan, legislative rules on deficits, a fiscal oversight board, and more reliable and timely data.

If I were a Puerto Rican considering statehood…I know how I would vote.

For the pointer I thank Felix Salmon.

Grist for Robin Hanson’s mill

It is hard to advise Greeks how to vote on July 5. Neither alternative – approval or rejection of the troika’s terms – will be easy, and both carry huge risks. A yes vote would mean depression almost without end. Perhaps a depleted country – one that has sold off all of its assets, and whose bright young people have emigrated – might finally get debt forgiveness; perhaps, having shriveled into a middle-income economy, Greece might finally be able to get assistance from the World Bank. All of this might happen in the next decade, or perhaps in the decade after that.

By contrast, a no vote would at least open the possibility that Greece, with its strong democratic tradition, might grasp its destiny in its own hands. Greeks might gain the opportunity to shape a future that, though perhaps not as prosperous as the past, is far more hopeful than the unconscionable torture of the present.

I know how I would vote.

Tweets to ponder

The main euro Q is whether the problem is Greece (so kicking them out solves problem) or is misaligned exch rates (so someone will be next)

That is from Austan Goolsbee.

Not in Greece, but news nonetheless

The Chinese stock market is tanking again, down more than seven percent today, seventeen percent or so over the last three days. Read David Keohane.

Puerto Rico isn’t going to pay up, and they announced this through the NYT.

Utrecht is going to experiment with a basic income scheme.

Central Russian officials crack down on yoga to limit the spread of occultism.

Would there (will there?) be contagion from Grexit?

If you put Greek total debt in perspective, it’s smaller than that of many other EU nations, including Portugal. And that is as a percentage of gdp. Furthermore most of the remaining Greek debt is held by public sector institutions.

The difference of course is that Greece is being run by The Not Very Serious People. Portugal is often described as the next weakest link in the eurozone, but Portuguese politics are not nearly so…vivid. The amount of fiscal consolidation they have done is more or less accepted by the public. That makes Portugal more likely to survive, and it also makes the EU more willing to bail out Portugal, and extend any bailout if needed.

The performance of Syriza won’t encourage European voters to take chances on other less tested, left-wing parties, and that also militates against contagion.

(In the meantime, I don’t understand why Anglo-American left-wing intellectuals have been egging on the Syriza performance. Even if you think the current mess is mostly Germany’s fault in normative terms, the marginal product of the Syriza government still has been catastrophically negative. It wasn’t long ago that Greek banks were raising fresh equity and were said to have recovered. Here is Krugman’s defense, I find Anders Aslund more persuasive, furthermore Grexit would mean more austerity not less.)

For contagion, here are a few possible problems:

1. If Greece does reasonably well after Grexit, many others will ask why should they not follow suit and that could turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy. I’ll bet against that, but it’s worth mentioning. It also would take a while to develop.

2. As Greece exists, the ECB has to express a strength of commitment to the other debt-ridden nations. Delivering the right message is tricky here, because for legal and public opinion reasons the ECB cannot make the kind of unconditional commitments the Fed can. So markets might become unhappy with the decline in creative ambiguity at the ECB. I believe the ECB can finesse this one — in essence the message “we’ll help any EU government which is more responsible than Syriza” is fairly credible and in fact is already being signaled by the Eurogroup. So I’ll bet against this problem too, but still it could happen.

3. If only for geopolitical and also humanitarian reasons, the EU cannot wash its hands of Greece, even if Greece leaves the EU. But deciding how to deal with Greece might bring considerable disagreements among the remaining eurozone nations, as might the attempt to spell out exit procedures. Festering, emotional issues are not good for dysfunctional political unions, and a lot of the “hold the line” solidarity might melt away with Grexit.

4. There might be a very slow form of contagion as the reversibility of the currency union becomes better and better known and people start seeing it as little more than a currency board arrangement. As with #3, that could become an ongoing problem, still it doesn’t quite seem dramatic enough to produce rapid contagion.

Here is my previous post on the topic. Robin Wigglesworth surveys a variety of differing views on contagion and other short-run effects. I wrote this post last night, so if I am wrong it might already be evident by now.

China comparison of the day

1. GDP growth of 7% w/profit growth of 0.6%=really bad managers or 2. GDP growth not really 7%. Choose 1 or 2

#China

That is from Christopher Balding. Let’s not forget that the Greece story may end up as relatively small by comparison.

King Cotton and Deadweight Loss

In our textbook, Tyler and I write:

Farmers use the subsidized water to transform desert into prime agricultural land. But turning a California desert into cropland makes about as much sense as building greenhouses in Alaska! America already has plenty of land on which cotton can be grown cheaply. Spending billions of dollars to dam rivers and transport water hundreds of miles to grow a crop which can be grown more cheaply in Georgia is a waste of resources, a deadweight loss. The water used to grow California cotton, for example, has much higher value producing silicon chips in San Jose or as drinking water in Los Angeles than it does as irrigation water.

In Holy Crop, part of Pro-Publica’s excellent, in-depth series on the water crisis the authors concur:

Getting plants to grow in the Sonoran Desert is made possible by importing billions of gallons of water each year. Cotton is one of the thirstiest crops in existence, and each acre cultivated here demands six times as much water as lettuce, 60 percent more than wheat. That precious liquid is pulled from a nearby federal reservoir, siphoned from beleaguered underground aquifers and pumped in from the Colorado River hundreds of miles away.

…Over the last 20 years, Arizona’s farmers have collected more than $1.1 billion in cotton subsidies, nine times more than the amount paid out for the next highest subsidized crop. In California, where cotton also gets more support than most other crops, farmers received more than $3 billion in cotton aid.

…If Arizona’s cotton farmers switched to wheat but didn’t fallow a single field, it would save some 207,000 acre-feet of water — enough to supply as many as 1.4 million people for a year.

…The government is willing to consider spending huge amounts to get new water supplies, including building billion-dollar desalinization plants to purify ocean water. It would cost a tiny fraction of that to pay farmers in Arizona and California more to grow wheat rather than cotton, and for the cost of converting their fields. The billions of dollars of existing subsidies already allocated by Congress could be redirected to support those goals, or spent, as the Congressional Budget Office suggested, on equipment and infrastructure that helps farmers use less water.

“There is enough water in the West. There isn’t any pressing need for more water, period,” Babbitt said. “There are all kinds of agriculture efficiencies that have not been put into place.”