Category: Current Affairs

The Greeks vote for “austerity now”

And I do mean now. With the primary surplus gone, this means further cuts in government spending. Confiscation of bank deposits and banks flat out of cash. Continuation of capital controls. Difficulties in consummating international or even domestic transactions. Problems in paying for fuel, seeds, fertilizer, and medicines.

Austerity now.

Here are some possible Greek plans, but everything remains up in the air. If nothing else, I give them credit for their stones. Let’s hope this works out in the longer run, it sure won’t over the course of the next year or two.

How long does it take to introduce a new currency?

Wintergerst says introducing a new currency typically takes at least six months, and sometimes as long as two years. Artists must draw the notes, security experts then add anti-counterfeiting measures such as watermarks and special inks, and bank officials need to plan how much of each denomination is needed and get the money to banks.

“The most challenging thing was to establish efficient distribution and make sure the new currency was available everywhere,” said Boris Raguz, head of the Treasury Directory at Croatia’s central bank, who in 1993 oversaw the introduction of the country’s currency, the kuna, after the breakup of Yugoslavia.

That is from Matthew Campbell and Alex Webb. Here is a declaration signed by 246 Greek professors — can you guess what it says?

Might Greece see some version of hyperinflation?

Keep in mind that things can go badly under either a yes or no vote today. (I am not even sure the referendum result will make such a difference, since it is all in the subsequent deal, or lack thereof, and the terms would be different anyway.) Yet I do not think a hyperinflation is the likely result.

As things stand, Greece could run out of euros in well under a week. That is a deflationary pressure. To be sure, Greek companies are already starting to print up various kinds of scrip. But those will be media of exchange priced in terms of euros, not new media of account. The script will to some extent stabilize against deflationary pressures, by preventing a total economic collapse, but they won’t themselves cause hyperinflation. If one company prints up too much scrip, the value of that brand will fall in terms of euros. In contrast, a “domestic” medium of account is usually firmly entrenched in a classic hyperinflation.

Greece may eventually move away from the euro as a medium of account, but that likely would happen only once an alternative payment medium — perhaps the new drachma — is relatively stable in value. Again, there is no expected hyperinflation. Deposit confiscation will be required long before hyperinflation is an option, do note that is not exactly a reassuring thought. In fact hyperinflation is too slow and inefficient a way to steal from the citizenry in this setting.

An interesting set of issues revolves around bill prepayment. If you didn’t know, electronic transfers within the country are still allowed, so everyone is trying to prepay bills rather than receive a haircut on their deposits (see the link above). Various events could speed up or slow down these pressures, for instance greater stability combined with outside aid could limit deposit confiscation risk and thus lower bank deposit velocity. Alternatively, greater risk could cut either way. It could lead to more prepayment and higher velocity, but it also could induce suppliers to take actions to make prepayment harder. There are some complex options here, though still I don’t see them giving rise to a hyperinflation. Again, the key point is that even under Grexit scenarios the euro remains a medium of account for a while still, and deflationary deposit confiscation will be needed before hyperinflation could extract enough seigniorage.

As Frances Coppola points out, Grexit is a process not an event and many of the early and indeed intermediate steps already are underway.

Greece and Syriza lost the public relations battle

One of the most striking aspects of the Greek situation is just how much the Greek government has lost the public relations battle. They have lost it among the social democracies, and they have lost it most of all with the other small countries in Europe. They retain some sympathy in the American government, but we are not willing to put any money on the table and basically we want the European Union to clean up the problems for us.

If you look at the progressive economists, Stiglitz, Krugman, Piketty and Sachs all recommend a “no” vote on the referendum. Though they would not frame it this way, they are advocating a kind of extra austerity for the purposes of a greater long-run good; Greece’s primary surplus vanished some time ago, so signaling a break with Europe will only make matters tougher. You could call this “properly mood affiliated austerity,” cloaked by strange presumptions about bargaining, namely the view that a “no” vote will induce a more favorable offer. It seems, with their on the ground understanding, most Greek economists are strongly in the “yes” camp.

The progressives do have some good points and I absolutely favor significant debt relief for Greece. That said, the Greek government has handled the last few months so badly it really is incumbent on them to show they will do better. I don’t see many signs in that direction, quite the contrary, and any reasonable democratic government will ask for Greek institutional progress before putting up much more in the way of money. The entire handling of Greferendum should alert the progressives that they have been egging on the wrong horse; the heroic Hugo Dixon nails it.

I take the progressive “clustering out on a limb” here as a sign that, for better or worse, progressivism as an ideology has reached and indeed gone beyond its high water mark. The progressives are siding with a corrupt, clientist state, which won’t cut its defense spending down to Nato norms, against some admittedly imperfect social democracies, thereby sustaining the meme of powerful aggressor vs. victim, Arnold Kling telephone.

Interfluidity has an interesting but quite wrong post on how to think about Greece. International relations simply could not be run on the principles he advocates, most of all in conjunction with democratic nation states. His weakest point becomes evident when he writes:

Among creditors, a big catchphrase now is “moral hazard”. We cannot be too kind to Greece, we cannot forgive their debt with few string attached, because what kind of precedent would that set? If bad borrowers, other sovereigns, got the idea that they can overborrow without consequence, if Spanish and Portuguese populists perceive perhaps a better deal is on offer, they might demand that. They might continue to borrow and expect forgiveness, and where would it end except for the bankruptcy of the good Europeans who actually produce and save?

The nerve. The fucking nerve. Lenders, having been made nearly whole on their ill-conceived, profit-motivated punts, now fear that if anybody is nice to somebody who doesn’t deserve it, where will it end? I’d resort to that cliché about chutspa, the kid who murders his parents then seeks leniency ‘cuz he’s an orphan. But it’s really too cute for the occasion.

That’s a non-answer, with anger filling in for the required substance as to why Germany and others should allow this. “Your government is making things much worse. If you want to borrow so much more from us, you have to play by the rules and also stop spitting in our face and calling us Nazis and terrorists while negotiating” is more relevant — and yes relevant is the right word here — than any point he makes.

A political program has to be something that voters could at least potentially believe, and international negotiations therefore cannot stray too far from common-sense morality, including when it comes to creditor-debtor relations. That is the point which today’s progressive economists are running away from as fast as is humanly possible. And for all the Buchanan-esque and public choice points about “rules of the game” this one about common sense morality unfortunately has ended up as the most important.

Look at this way: if you lost a public relations battle to Germany, you are probably doing something very badly wrong.

China facts of the day

Greece is small, China is large:

The Shanghai Composite has now fallen 12.1 per cent since Monday, its third consecutive week of double-digit losses since hitting a seven-year high on June 12.

The Shanghai index is firmly in bear market territory, down 28.6 per cent since the June peak, while the tech-heavy Shenzhen Composite has fallen 33.2 per cent.

There were also signs on Friday that the stock market turmoil is beginning to reverberate beyond China. The Australian dollar, often traded as a proxy for China growth, is down 1.2 per cent to a six-year low of US$0.7539.

The 21st Century Business Herald, a Chinese daily newspaper, on Friday quoted multiple futures traders as saying they had received phone calls from the China Financial Futures Exchange instructing them not to short the market.

That is from Gabriel Wildau at the FT. China’s brokerages have pledged over $19 billion to help “stabilize” the market, not usually a good sign.

That said, flights into Greece for July-September seem to be down by up to fifty percent.

Southern Italy, Europe’s soft underbelly

Scott Sumner has the scoop:

In one important respect southern Italy is different from Greece. Like eastern Germany, southern Italy is part of a larger and more prosperous fiscal union. For many decades, Italy has been doing the things that American progressives would recommend, pouring lots of fiscal stimulus into the south, to build up the economy. But nothing seems to work. Indeed from Greece to Italy to southern Iberia, the entire southern tier of Europe is doing quite poorly. But why? And what can America learn from the failure of Italian policies aimed at boosting the mezzogiorno?

American progressives will sometimes argue that we have much to learn from the successful welfare states in northern Europe. Perhaps that’s true. But I’d have a bit more confidence in that claim if they could explain what we have to learn from the failed welfare states in southern Europe. Indeed I’d have more confidence in progressive ideas if they even had an explanation for the failed welfare states of southern Europe. But I don’t ever recall reading a progressive explanation. Indeed the only explanations I’ve ever read are conservative explanations, tied to cultural differences.

PS. The mezzogiorno has roughly 1/3 of Italy’s 60 million people, making it almost twice as populous as Greece. In absolute terms, incomes there (17,200 euros GDP per person in 2014) are far lower than among American blacks or Hispanics. In contrast, GDP per person in northern Italy was about 31,500 euros in 2014. And while the gap between eastern and western Germany is narrowing, the gap in Italy is widening. Why?

Puerto Rico fact of the day

…because of an obscure law known as the Jones Act, which bans foreign vessels from shipping goods between U.S. ports, businesses in Puerto Rico have to use the U.S. merchant marine to import anything. They can’t just hire whatever boats and crew are available, which makes shipping even more expensive. The cost of transportation in Puerto Rico is twice that in the neighboring Caribbean nations…

Why is Obamacare still unpopular?

After all of this and two complete open enrollments, only 40% of those who are eligible for Obamacare have signed up—far below the proportion of the market insurers have historically needed to assure a sustainable risk pool.

If this were a private enterprise enjoying these kinds of benefits [ namely legal coercion], and only sold its product to 40% of the market, its CEO would be fired.

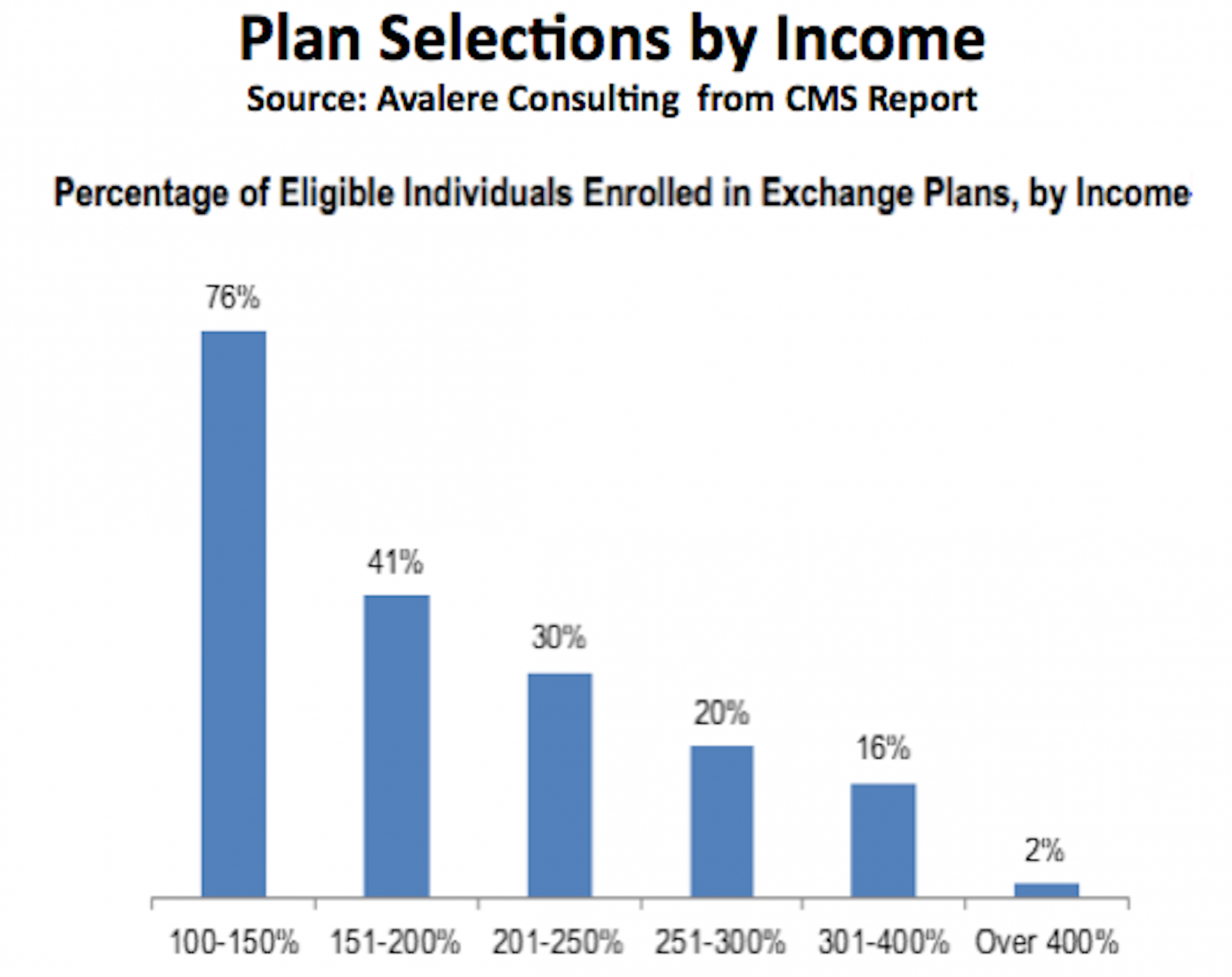

Looking at this picture, only 20% of those eligible for Obamacare, who make between 251% and 300% of the poverty level, bought Obamacare. Why?

The Obama administration will in fact be increasing the subsidies it will pay to insurance companies.

The legal problem with the blockchain

“The law will not treat a ledger record as authoritative if everyone knows that the current longest chain contains blocks generated by an anonymous attacker who replaced a bit of history that was chronologically prior,” he says. “In financial markets there’s always a mechanism to correct an attack. In a blockchain there is no mechanism to correct it — people have to accept it.”

That is an FT quotation from Robert Sams, the article is interesting more generally, focusing on Wall Street’s attempt to incorporate the blockchain in settlement in some manner.

The Battle for Greece

The Greek story is being framed as a battle between the Greeks and the Germans and thus between spending and austerity. But this frame can’t make sense of the fact that, win or lose, large numbers of Greeks will vote for austerity on Sunday.

To understand what’s really going on, listen to this remarkable interview between NPR’s Robin Young and Nikolalos Voglis, a restaurant owner in Athens. The interview begins with a discussion of the crisis. No one has cash or credit and Voglis’s restaurant is basically shuttered. Young then asks Voglis how he will vote on Sunday and he replies, “Definitely, Yes.” Young is surprised, she tries to clarify, you will vote, “even for more austerity?” “That’s right,” he replies.

Following the conventional frame, Young finds this difficult to understand and she pushes back against Voglis with all the conventional arguments. She quotes Paul Krugman saying that the problem isn’t really Greece’s doing, that the IMF and EU are being too tough on Greece, that Greece has done a lot of cutting already and so on. Voglis responds:

We are on the right track but unfortunately the job wasn’t completed. We are a country in the European Community which has the biggest public sector in Europe. And all of us in the private sector spend millions to support the situation. So the only way that Greece can become a true Western country…is to make these reforms.

…Look the main problem in this country is the public sector. There is no other problem. Entrepreneurs here are very, very competitive. We have to let this thing, this monster that we call the public sector, it has to go, it has to finish. This is the main issue.

Many Greeks are sick and tired of the bloated public sector and its corruption, inefficiency and waste. In this frame, the Greek story is not fundamentally about Greeks versus Germans it’s about the Greek people versus their government–the Germans have simply been the vehicle that has brought the Greeks to their kairotic moment. The Greeks want normalcy, as the Poles did after communism. If the Yes vote wins on Sunday it will be the Greeks voting not just against the current administration but against the entire state apparatus.

Fear the multiple marginalization

Upcoming Conversations with Tyler

The next three will be with Luigi Zingales, Dani Rodrik, and Clifford Asness, you will find the details here, all coming this fall!

China and the high cost of hiring labor

…[recent developments] may well mark the beginning of an important longer-term shift in China’s labor market and policies: the State Council lowered employers’ required contributions to two social insurance programs, injury and maternity insurance, a move it said would save firms 27 billion renminbi a year (see the China Labour Bulletin for an English-language summary). Yes, I know this sounds boring and technical, so why is it important? Because it starts to address one of the biggest but least-known issues in China’s job market: the very high costs employers face to hire workers.

It is not a very well-known fact that China has some of the toughest labor regulations in the world, and some of the highest required contribution rates to social insurance programs. As a result, the “labor wedge”–the percentage of the total cost of an employee that comes from things other than wages–in China is around 45%, as high as in a number of European countries (this is according to an estimate by John Giles in a World Bank paper;…

This fact does not square with the widespread perception of China as a nation of sweatshops employing hordes of migrant workers, and indeed is a relatively recent development stemming from the 2008 Labor Contract Law. But China’s problem with these generous worker protections is ultimately the same one that many other developing countries have encountered: strong legal protections and generous insurance programs are so expensive that in practice they only become available to part of the workforce. Effectively China has two labor markets: one for urban white-collar jobs with all the legal protections, and one for blue-collar jobs held by rural migrant workers that generally lack the full set of benefits.

That is yet another neglected China story…

The view from Vilnius, part II

When Greece’s finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, in an early round of negotiations in Brussels, complained that Greek pensions could not be cut any further, he was reminded bluntly by his colleague from Lithuania that pensioners there have survived on far less. Lithuania, according to the most recent figures issued by Eurostat, the European statistics agency, spends 472 euros, about $598, per capita on pensions, less than a third of the 1,625 euros spent by Greece. Bulgaria spends just 257 euros. This data refers to 2012 and Greek pensions have since been cut, but they still remain higher than those in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Croatia and nearly all other states in eastern, central and southeastern Europe.

There is more from Andrew Higgins in the NYT here.

Planetary Defense is a Public Good

Today is Asteroid Day, the anniversary of the largest asteroid impact in recent history, the June 30, 1908 Siberian Tunguska asteroid strike. The Tunguska asteroid was only about 40 meters in size but the impact was 1000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima nuclear bomb.

Large asteroid strikes are low-probability, high-death events–so high-death that by some estimates the probability of dying from an asteroid strike is on the same order as dying in an airplane crash. To mark asteroid day, events around the world, including here at the observatory at George Mason University, will discuss asteroids and how we can protect our civilization.

Tyler and I are signatories to the 100X Declaration which reads in part:

There are a million asteroids in our solar system that have the potential to strike Earth and destroy a city, yet we have discovered less than 10,000….

Therefore, we, the undersigned, call for…A rapid hundred-fold acceleration of the discovery and tracking of Near-Earth Asteroids to 100,000 per year within the next ten years.

I am also a contributor to an Indiegogo campaign to develop a planetary defense system–yes, seriously! I don’t expect the campaign to succeed because, as our principles of economics textbook explains, too many people will try to free ride. But perhaps the campaign will generate some needed attention. In the meantime, check out this video on public goods and asteroid defense from our MRU course (as always the videos are free for anyone to use in the classroom.)

By the way, can you identify the easter egg to growing up in the 1980s?