Category: Education

My excellent Conversation with John Amaechi

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. As I said on Twitter, John has the best “podcast voice” of any CWT guest to date. Here is the episode summary:

John Amaechi is a former NBA forward/center who became a chartered scientist, professor of leadership at Exeter Business School, and New York Times bestselling author. His newest book, It’s Not Magic: The Ordinary Skills of Exceptional Leaders, argues that leadership isn’t bestowed or innate, it’s earned through deliberate skill development.

Tyler and John discuss whether business culture is defined by the worst behavior tolerated, what rituals leadership requires, the quality of leadership in universities and consulting, why Doc Rivers started some practices at midnight, his childhood identification with the Hunchback of Notre Dame and retreat into science fiction, whether Yoda was actually a terrible leader, why he turned down $17 million from the Lakers, how mental blocks destroyed his shooting and how he overcame them, what he learned from Jerry Sloan’s cruelty versus Karl Malone’s commitment, what percentage of NBA players truly love the game, the experience of being gay in the NBA and why so few male athletes come out, when London peaked, why he loved Scottsdale but had to leave, the physical toll of professional play, the career prospects for 2nd tier players, what distinguishes him from other psychologists, why personality testing is “absolute bollocks,” what he plans to do next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Of NBA players as a whole, what percentage do you think truly love the game?

AMAECHI: It’s a hard question to answer. Well, let me give a number first, otherwise, it’s just frustrating. 40%. And a further 30% like the game, and 20% of them are really good at the game and they have other things they want to do with the opportunities that playing well in the NBA grants them.

But make no mistake, even that 30% that likes the game and the 40% that love the game, they also know that they like what the game can give them and the opportunities that can grow for them, their families and generation, they can make a generational change in their family’s life and opportunities. It’s not just about love. Love doesn’t make you good at something. And this is a mistake that people make all the time. Loving something doesn’t make you better, it just makes the hard stuff easier.

COWEN: Are there any of the true greats who did not love playing?

AMAECHI: Yeah. So I know all former players are called legends, whether you are crap like me or brilliant like Hakeem Olajuwon, right? And so I’m part of this group of legends and I’m an NBA Ambassador as well. So I go around all the time with real proper legends. And a number of them I know, and so I’m not going to throw them under the bus, but it’s the way we talk candidly in the van going between events. It’s like, “Yeah, this is a job now and it was a job then, and it was a job that wrecked our knees, destroyed our backs, made it so it’s hard for us to pick up our children.”

And so it’s a job. And we were commodities for teams who often, at least back in those days, treated you like commodities. So yeah, there’s a lot of superstars, really, really excellent players. But that’s the problem, don’t conflate not loving the game. And also, don’t be fooled. In Britain there’s this habit of athletes kissing the badge. In football, they’ve got the badge on their shirt and they go, “Mwah, yeah.” If that fools you into thinking that this person loves the game, if them jumping into the stands and hugging you fools you into thinking that they love the game, more fool you.

COWEN: Michael Cage, he loved the game. Right?

But do note that most of the Conversation is not about the NBA.

Higher education is not that easy

More than two years into a conservative takeover of New College of Florida, spending has soared and rankings have plummeted, raising questions about the efficacy of the overhaul.

While state officials, including Republican governor Ron DeSantis, have celebrated the death of what they have described as “woke indoctrination” at the small liberal arts college, student outcomes are trending downward across the board: Both graduation and retention rates have fallen since the takeover in 2023.

Those metrics are down even as New College spends more than 10 times per student what the other 11 members of the State University System spend, on average. While one estimate last year put the annual cost per student at about $10,000 per member institution, New College is an outlier, with a head count under 900 and a $118.5 million budget, which adds up to roughly $134,000 per student.

Here is the full story. Maybe you think this is exaggerated, but I never hear from anyone that the venture is going well. There is a reason for that. A tiny bit you can blame on the FAA.

Good job people, congratulations…

“Sonnet 4.5 does complete replication checks of an econpaper.”

That is Kevin Bryan, here is more from Ethan Mollick.

Zambia fact of the day

It is worse than you think:

Of 360,000 children aged 15 in Zambia only five (not 5%, 5 total) could read at “globally proficient levels.”

My excellent Conversation with Steven Pinker

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Steven probe these dimensions of common knowledge—Schelling points, differential knowledge, benign hypocrisies like a whisky bottle in a paper bag—before testing whether rational people can actually agree (spoiler: they can’t converge on Hitchcock rankings despite Aumann’s theorem), whether liberal enlightenment will reignite and why, what stirring liberal thinkers exist under the age 55, why only a quarter of Harvard students deserve A’s, how large language models implicitly use linguistic insights while ignoring linguistic theory, his favorite track on Rubber Soul, what he’ll do next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Surely there’s a difference between coordination and common knowledge. I think of common knowledge as an extremely recursive model that typically has an infinite number of loops. Most of the coordination that goes on in the real world is not like that. If I approach a traffic circle in Northern Virginia, I look at the other person, we trade glances. There’s a slight amount of recursion, but I doubt if it’s ever three loops. Maybe it’s one or two.

We also have to slow down our speeds precisely because there are not an infinite number of loops. We coordinate. What percentage of the coordination in the real world is like the traffic circle example or other examples, and what percentage of it is due to actual common knowledge?

PINKER: Common knowledge, in the technical sense, does involve this infinite number of arbitrarily embedded beliefs about beliefs about beliefs. Thank you for introducing the title with the three dots, dot, dot, dot, because that’s what signals that common knowledge is not just when everyone knows that everyone knows, but when everyone knows that everyone knows that and so on. The answer to your puzzle — and I devote a chapter in the book to what common knowledge — could actually consist of, and I’m a psychologist, I’m not an economist, a mathematician, a game theorist, so foremost in my mind is what’s going on in someone’s head when they have common knowledge.

You’re right. We couldn’t think through an infinite number of “I know that he knows” thoughts, and our mind starts to spin when we do three or four. Instead, common knowledge can be generated by something that is self-evident, that is conspicuous, that’s salient, that you can witness at the same time that you witness other people witnessing it and witnessing you witnessing it. That can grant common knowledge in a stroke. Now, it’s implicit common knowledge.

One way of putting it is you have reason to believe that he knows that I know that he knows that I know that he knows, et cetera, even if you don’t literally believe it in the sense that that thought is consciously running through your mind. I think there’s a lot of interplay in human life between this recursive mentalizing, that is, thinking about other people thinking about other people, and the intuitive sense that something is out there, and therefore people do know that other people know it, even if you don’t have to consciously work that through.

You gave the example of norms and laws, like who yields at an intersection. The eye contact, though, is crucial because I suggest that eye contact is an instant common knowledge generator. You’re looking at the part of the person looking at the part of you, looking at the part of them. You’ve got instant granting of common knowledge by the mere fact of making eye contact, which is why it’s so potent in human interaction and often in other species as well, where eye contact can be a potent signal.

There are even species that can coordinate without literally having common knowledge. I give the example of the lowly coral, which presumably not only has no beliefs, but doesn’t even have a brain with which to have beliefs. Coral have a coordination problem. They’re stuck to the ocean floor. Their sperm have to meet another coral’s eggs and vice versa. They can’t spew eggs and sperm into the water 24/7. It would just be too metabolically expensive. What they do is they coordinate on the full moon.

On the full moon or, depending on the species, a fixed number of days after the full moon, that’s the day where they all release their gametes into the water, which can then find each other. Of course, they don’t have common knowledge in knowing that the other will know. It’s implicit in the logic of their solution to a coordination problem, namely, the public signal of the full moon, which, over evolutionary time, it’s guaranteed that each of them can sense it at the same time.

Indeed, in the case of humans, we might do things that are like coral. That is, there’s some signal that just leads us to coordinate without thinking it through. The thing about humans is that because we do have or can have recursive mentalizing, it’s not just one signal, one response, full moon, shoot your wad. There’s no limit to the number of things that we can coordinate creatively in evolutionarily novel ways by setting up new conventions that allow us to coordinate.

COWEN: I’m not doubting that we coordinate. My worry is that common knowledge models have too many knife-edge properties. Whether or not there are timing frictions, whether or not there are differential interpretations of what’s going on, whether or not there’s an infinite number of messages or just an arbitrarily large number of messages, all those can matter a lot in the model. Yet actual coordination isn’t that fragile. Isn’t the common knowledge model a bad way to figure out how coordination comes about?

And this part might please Scott Sumner:

COWEN: I don’t like most ballet, but I admit I ought to. I just don’t have the time to learn enough to appreciate it. Take Alfred Hitchcock. I would say North by Northwest, while a fine film, is really considerably below Rear Window and Vertigo. Will you agree with me on that?

PINKER: I don’t agree with you on that.

COWEN: Or you think I’m not your epistemic peer on Hitchcock films?

PINKER: Your preferences are presumably different from beliefs.

COWEN: No. Quality relative to constructed standards of the canon…

COWEN: You’re going to budge now, and you’re going to agree that I’m right. We’re not doing too well on this Aumann thing, are we?

PINKER: We aren’t.

COWEN: Because I’m going to insist North by Northwest, again, while a very good movie is clearly below the other two.

PINKER: You’re going to insist, yes.

COWEN: I’m going to insist, and I thought that you might not agree with this, but I’m still convinced that if we had enough time, I could convince you. Hearing that from me, you should accede to the judgment.

I was very pleased to have read Steven’s new book

Who are the important intellectuals today, under the age of 55?

I do not mean public intellectuals, though they are an important category of their own. For this question in earlier times you might have mentioned Foucault, Nozick, or Jon Elster. They were public intellectuals of a sort, but they also carried considerable academic heft in their own right. They promoted ideas original to them.

So who today are the equivalents? Important, original thinkers. With impact. You look forward to their next book or proclamation. Under age 55. Bitte.

More corruption in the Harvard leadership

Harvard School of Public Health Dean Andrea A. Baccarelli received at least $150,000 to testify against Tylenol’s manufacturer in 2023 — two years before he published research used by the Trump administration to link the drug to autism, a connection experts say is tenuous at best.

Baccarelli served as an expert witness on behalf of parents and guardians of children suing Johnson & Johnson, the manufacturer of Tylenol at the time. U.S. District Court Judge Denise L. Cote dismissed the case last year due to a lack of scientific evidence, throwing out Baccarelli’s testimony in the process.

“He cherry-picked and misrepresented study results and refused to acknowledge the role of genetics in the etiology” of autism spectrum disorder or ADHD, Cote wrote in her decision, which the plaintiffs have since appealed.

Here is more from The Crimson.

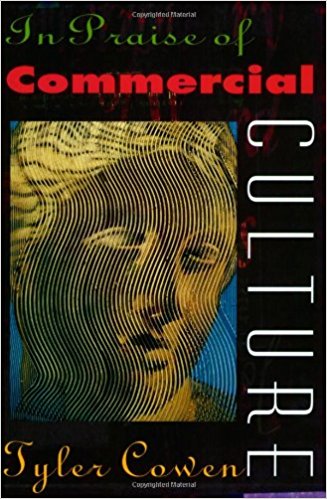

The Return of the MR Podcast: In Praise of Commercial Culture

The Marginal Revolution Podcast is back with new episodes! We begin with what I think is our best episode to date. We revisit Tyler’s 1998 book In Praise of Commercial Culture. This is the book that put Tyler on the map as a public intellectual. Tyler and I also wrote a paper, An Economic Theory of Avant-Garde and Popular Art, or High and Low Culture, exploring themes from the book. But does In Praise of Commercial Culture stand the test of time? You be the judge!

The Marginal Revolution Podcast is back with new episodes! We begin with what I think is our best episode to date. We revisit Tyler’s 1998 book In Praise of Commercial Culture. This is the book that put Tyler on the map as a public intellectual. Tyler and I also wrote a paper, An Economic Theory of Avant-Garde and Popular Art, or High and Low Culture, exploring themes from the book. But does In Praise of Commercial Culture stand the test of time? You be the judge!

Here’s one bit:

TABARROK: Here’s a quote from the book, “Art and democratic politics, although both beneficial activities, operate on conflicting principles.”

COWEN: So much of democratic politics is based on consensus. So much of wonderful art, especially new art, is based on overturning consensus, maybe sometimes offending people. All this came to a head in the 1990s, disputes over what the National Endowment for the Arts in America was funding. Some of it, of course, was obscene. Some of it was obscene and pretty good. Some of it was obscene and terrible.

What ended up happening is the whole process got bureaucratized. The NEA ended up afraid to make highly controversial grants. They spend more on overhead. They send more around to the states. Now, it’s much more boring. It seems obvious in retrospect. The NEA did a much better job in the 1960s, right after it was founded, when it was just a bunch of smart people sitting around a table saying, “Let’s send some money to this person,” and then they’d just do it, basically.

TABARROK: Right, so the greatness cannot survive the mediocrity of democratic consensus.

COWEN: There are plenty of good cases where government does good things in the arts, often in the early stages of some process before it’s too politicized. I think some critics overlook that or don’t want to admit it.

TABARROK: One of the interesting things in your book was that the whole history of the NEA, this recreates itself, has recreated itself many times in the past. The salon during the French painting Renaissance, the impressionists hated the salon, right?

COWEN: Right. And had typically turned them away because the works weren’t good enough.

TABARROK: There could be rent-seeking going on, right? The artists get control. Sometimes it’s democratic politics, but sometimes it’s some clique of artists who get control and then funnel the money to their friends.

COWEN: French cinematic subsidies would more fit that latter model. It’s not so much that the French voters want to pay for those movies, but a lot of French government is controlled by elites. The elites like a certain kind of cinema. They view it as a counterweight to Hollywood, preserving French culture. The French still pay for or, indirectly by quota, subsidize a lot of films that just don’t really even get released. They end up somewhere and they just don’t have much impact flat out.

Here’s the episode. Subscribe now to take a small step toward a much better world: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube.

Girls improve student mental health

Using individual-level data from the Add Health surveys, we leverage idiosyncratic variation in gender composition across cohorts within the same school to examine whether being exposed to a higher share of female peers affects mental health and school satisfaction. We find that being exposed to a higher proportion of female peers, despite only improving school satisfaction for boys, improves mental health for both boys and girls. The benefits are greater among boys of low socioeconomic backgrounds, who would otherwise be more likely to be exposed to violent and disruptive peers. We find suggestive evidence that the mechanisms driving our findings are consistent with stronger school friendships for boys and better self-image and grades for girls.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Monica Deza and Maria Zhu.

What should I ask Alison Gopnik?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. Here is Wikipedia:

Alison Gopnik (born June 16, 1955) is an American professor of psychology and affiliate professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. She is known for her work in the areas of cognitive and language development, specializing in the effect of language on thought, the development of a theory of mind, and causal learning. Her writing on psychology and cognitive science has appeared in Science, Scientific American, The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, New Scientist, Slate and others. Her body of work also includes four books and over 100 journal articles…

Gopnik has carried out extensive work in applying Bayesian networks to human learning and has published and presented numerous papers on the topic…Gopnik was one of the first psychologists to note that the mathematical models also resemble how children learn.

Gopnik is known for advocating the “theory theory” which postulates that the same mechanisms used by scientists to develop scientific theories are used by children to develop causal models of their environment.

Here is her home page. So what should I ask her?

H1-B visa fees and the academic job market

Assume the courts do not strike this down (perhaps they will?).

Will foreigners still be hired at the entry level with an extra 100k surcharge? I would think not,as university budgets are tight these days. I presume there is some way to turn them down legally, without courting discrimination lawsuits?

What if you ask them to accept a lower starting wage? A different deal in some other manner, such as no summer money or a higher teaching load? Is that legal? Will schools have the stomach to even try? I would guess not. Is there a way to amortize the 100k over five or six years? What if the new hire leaves the institution in year three of the deal?

In economics at least, a pretty high percentage of the graduate students at top institutions do not have green cards or citizenships.

So how exactly is this going to work? There are not so many jobs in Europe, not enough to absorb those students even if they wish to work there. Will many drop out right now? And if the flow of graduate students is not replenished, given that entry into the US job market is now tougher, how many graduate programs will close up?

Will Chinese universities suddenly hire a lot more quality talent?

Here is some related discussion on Twitter.

As they say, solve for the equilibrium…

From the comments

I am a high school teacher. As this study finds, banning phones hurts our best students. Unlike Tyler, I do have a problem with these policies. Studies like this dont even measure the ways that phones help our best students the most: they allow students to access real teachers, better teachers, sources of knowledge and learning that are beyond what they are stuck with in our public schools. There are many actions we could take that would boost grades. We could adopt singapore’s culture or the Japanese juku system. We could become as draconian as you like to boost grades for low-performing students. But to what end? Maybe there is one Peter Scholze who could boost his early learning by 5 pct, even 100 or more pct depending on what schhol he is in, with a phone. Is banning it from him worth boosting the algebra 1 scores of 20,000 future real estate salesman by 3 percent? Phones are new. Teachers have no idea how to use them. They are devices that contain the entire world’s knowledge and kids want to use them – and we are banning them? Any teacher who wants to ban phones is taking the easy way out.

That is from Frank. A broader but related point is that a school without smartphones probably cannot teach its students AI — one of the most useful things for a person to learn nowadays. As Frank indicates, you should be very suspicious that the smart phone banners take absolutely no interest in measuring their possible benefits. We economists call it cost-benefit analysis. If you wish to argue the costs are higher than the benefits, fine, that can be debated. If you are not trying to measure the benefits, I say you are not trying to do science or to approach the problem objectively.

And from a later post, again Frank:

Academic Human Capital in European Countries and Regions, 1200-1793

We present new annual time-series data on academic human capital across Europe from 1200 to 1793, constructed by aggregating individual-level measures at three geographic scales: cities, present-day countries (as of 2025), and historically informed macro-regions. Individual human capital is derived from a composite index of publication outcomes, based on data from the Repertorium Eruditorum Totius Europae (RETE) database. The macro-regional classifications are designed to re ect historically coherent entities, offering a more relevant perspective than modern national boundaries. This framework allows us to document key patterns, including the Little Divergence in academic human capital between Northern and Southern Europe, the effect of the Black Death and the Thirty Years’ War on academic human capital, the respective contributions of academies and universities, regional inequality within the Holy Roman Empire, and the distinctiveness of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Here is the full paper by Matthew Curtisa, David de la Croix, Filippo Manfredinib, and Mara Vitale. Via the excellent Samir Varma.

New print edition of Works in Progress

Amazing, here is the site: “The print edition contains everything you can get online, plus a lot more: print-exclusive columns, beautiful art and design, letters from our readers and editors, and visual explainers of technology.”

What should I ask Cass Sunstein?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him soon. Most of all (but not exclusively) about his three recent books Liberalism: In Defense of Freedom, Manipulation: What It Is, Why It Is Bad, What To Do About It, and Imperfect Oracle: What AI Can and Cannot Do.

So what should I ask him? Here is my previous CWT with Cass.

asdf wrote: