Category: Education

What should I ask Jimmy Wales?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is his uh…Wikipedia page. So what should I ask?

A new RCT on banning smartphones in the classroom

Widespread smartphone bans are being implemented in classrooms worldwide, yet their causal effects on student outcomes remain unclear. In a randomized controlled trial involving nearly 17,000 students, we find that mandatory in-class phone collection led to higher grades — particularly among lower-performing, first-year, and non-STEM students — with an average increase of 0.086 standard deviations. Importantly, students exposed to the ban were substantially more supportive of phone-use restrictions, perceiving greater benefits from these policies and displaying reduced preferences for unrestricted access. This enhanced student receptivity to restrictive digital policies may create a self-reinforcing cycle, where positive firsthand experiences strengthen support for continued implementation. Despite a mild rise in reported fear of missing out, there were no significant changes in overall student well-being, academic motivation, digital usage, or experiences of online harassment. Random classroom spot checks revealed fewer instances of student chatter and disruptive behaviors, along with reduced phone usage and increased engagement among teachers in phone-ban classrooms, suggesting a classroom environment more conducive to learning. Spot checks also revealed that students appear more distracted, possibly due to withdrawal from habitual phone checking, yet, students did not report being more distracted. These results suggest that in-class phone bans represent a low-cost, effective policy to modestly improve academic outcomes, especially for vulnerable student groups, while enhancing student receptivity to digital policy interventions.

That is from a recent paper by Alp Sungu, Pradeep Kumar Choudhury, and Andreas Bjerre-Nielsen. Note with grades there is “an average increase of 0.086 standard deviations.” I have no problem with these policies, but it mystifies me why anyone would put them in their top five hundred priorities, or is that five thousand? Here is my earlier post on Norwegian smart phone bans, with comparable results.

My Hope Axis podcast with Anna Gát

Here is the YouTube, here is transcript access, here is their episode summary:

The brilliant @tylercowen joins @TheAnnaGat for a lively, wide-ranging conversation exploring hope from the perspective of insiders and outsiders, the obsessed and the competitive, immigrants and hard workers. They talk about talent and luck, what makes America unique, whether the dream of Internet Utopia has ended, and how Gen-Z might rebel. Along the way: Jack Nicholson, John Stuart Mill, road trips through Eastern Europe, the Enlightenment of AI, and why courage shapes the future.

Excerpt:

Tyler Cowen: But the top players I’ve met, like Anand or Magnus Carlsen or Kasparov, they truly hate losing with every bone in their body. They do not approach it philosophically. They can become very miserable as a result. And that’s very far from my attitudes. It shaped my life in a significant way.

Anna Gát: I was so surprised. I was like, what? But actually, what? In Maggie Smith-high RP—what? This never occurred to me that losing can be approached philosophically.

Tyler Cowen: And I think always keeping my equanimity has been good for me, getting these compound returns over long periods of time. But if you’re doing a thing like chess or math or sports that really favors the young, you don’t have all those decades of compound returns. You’ve got to motivate yourself to the maximum extent right now. And then hating losing is super useful. But that’s just—those are not the things I’ve done. The people who hate losing should do things that are youth-weighted, and the people who have equanimity should do things that are maturity and age-weighted with compounding returns.

Excellent discussion, lots of fresh material. Here is the Hope Axis podcast more generally. Here is Anna’s Interintellect project, worthy of media attention. Most of all it is intellectual discourse, but it also seems to be the most successful “dating service” I am aware of.

The politics of depression in young adults

From a recent paper by Catherine Gimbrone, et.al.:

From 2005 to 2018, 19.8% of students identified as liberal and 18.1% identified as conservative, with little change over time. Depressive affect (DA) scores increased for all adolescents after 2010, but increases were most pronounced for female liberal adolescents (b for interaction = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.32), and scores were highest overall for female liberal adolescents with low parental education (Mean DA 2010: 2.02, SD 0.81/2018: 2.75, SD 0.92). Findings were consistent across multiple internalizing symptoms outcomes. Trends in adolescent internalizing symptoms diverged by political beliefs, sex, and parental education over time, with female liberal adolescents experiencing the largest increases in depressive symptoms, especially in the context of demographic risk factors including parental education.

Here is the link. This is further evidence for what is by now a well-known proposition.

The evolution of the economics job market

In the halcyon days of 2015-19, openings on the economics job market hovered at around 1900 per year. In 2020, Covid was a major shock, but the market bounced back quickly in 2021 and 2022. Since then, though, the market has clearly been in a funk. 2023, my job market year, saw a sudden dip in postings. 2024 was even worse, with openings falling 16% lower than the 2015-19 average.

At the time, the sudden fall in 2023 seemed mysterious—it was an otherwise healthy year for the broader labor market. In hindsight, it seems like the 2021-22 recovery masked some underlying weakness. The 2020 job market had 500 fewer openings than the 2014-19 average; 2021 and 2022 together produced only around 100 more jobs than the 2014-19 average. In other words, the recovery never made up for the pandemic; by this crude logic, around 400 economist jobs were “destroyed”.

…And of course, all of this decline occurred before the litany of disasters that have recently hit the Econ job market. In May, Jerome Powell announced that the Federal Reserve—perhaps the largest employer of economists in America—would cut its workforce by 10%. The federal government has frozen hiring, as has the World Bank. Hit by the dual threat of fines and looming cuts to federal funding, Harvard, MIT, the University of Washington, Notre Dame, Northwestern University, among others, have announced hiring freezes and budget cuts.

Here is more from Oliver Kim, who also offers a much broader discussion of the meaning of all this.

Moving on Up

James Heckman and Sadegh Eshaghnia have launched a broadside in the WSJ against the Chetty-Hendren paper The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects. It’s a little odd to see this in the WSJ but since the Chetty-Hendren paper has been widely reported in the media, I suppose this is fair game. Recall the basic upshot of Chetty-Hendren is that neighborhoods matter and in particular

…the outcomes of children whose families move to a better neighborhood—as measured by the outcomes of children already living there—improve linearly in proportion to the amount of time they spend growing up in that area, at a rate of approximately 4% per year of exposure.

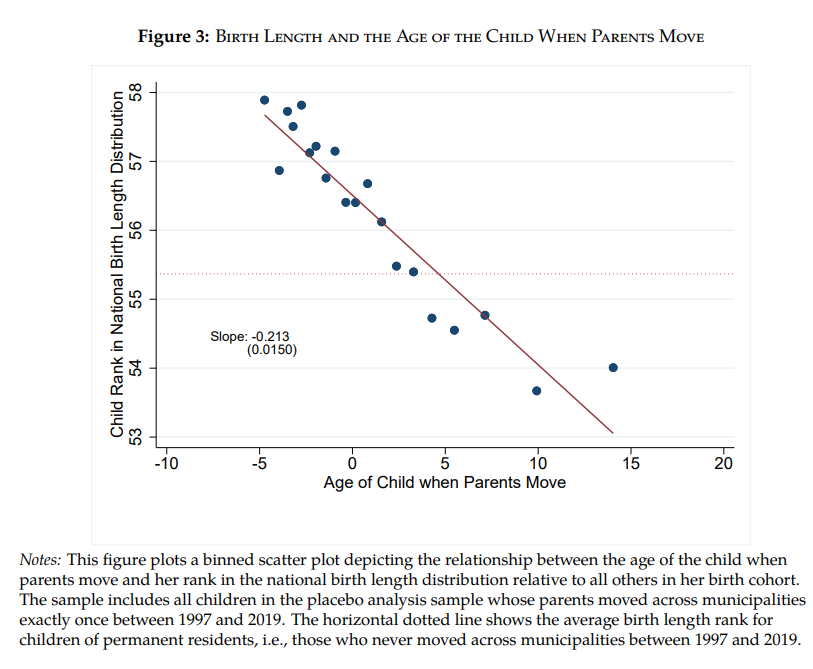

I am not going to referee this dispute but I did enjoy the audacity of one placebo test run by Eshaghnia. Eshaghnia runs the same statistical models as Chetty-Hendren but substitutes birth length (“the distance between a newborn’s head and heels”) instead of adult earnings and college attendance rates. Now, obviously, moving cannot affect birth length! Yet, Eshaghnia finds, in essence*, that children of parents who move to taller neighborhoods have taller children, in parallel with CH who find that children of parents who move to higher income neighborhoods have higher income children. Moreover, the covariance is stronger the earlier parents move. Since birth length is correlated with cognitive abilities and other later life outcomes this is highly suggestive that CH are not finding (pure) causal effects.

* I have simplified slightly for intuition. Technically, Eshaghnia shows that children’s birth‑length ranks align with the destination–origin permanent‑resident birth‑length difference, and that alignment is ≈0.044 stronger for each year earlier the move.

Addendum: Chetty et al. do not find similar results in California (see in particular Figure 2).

It would take more than one paper to establish these claims

Nonetheless these are interesting results, worthy of further examination:

The measurement of intelligence should identify and measure an individual’s subjective confidence that a response to a test question is correct. Existing measures do not do that, nor do they use extrinsic financial incentive for truthful responses. We rectify both issues, and show that each matters for the measurement of intelligence, particularly for women. Our results on gender and confidence in the face of risk have wider applications in terms of the measurement of “competitiveness” and financial literacy. Contrary to received literature, women are more intelligent than men, compete when they should in risky settings, and are more literate.

That is from the September JPE, by Glenn W. Harrison, Don Ross, and J. Todd Swarthout. Here are ungated versions of the paper. Here is Bryan Caplan on the limitations of any single paper.

What determines business school faculty pay?

We examine the determinants of business school faculty pay, using detailed data on compensation, research, teaching, and administrative service. We estimate that a top-tier journal publication is worth $116,000, with significant variation across disciplines. Second-tier publications are worth one-third as much, and other publications have no impact. Further analysis of salaries and cross-discipline publication records suggests that researchers are compensated based on the journals they publish in rather than the departments they belong to. Conference presentations and teaching evaluations have significant but smaller effects than top-tier publications. Faculty administrators earn a premium, with department chairs receiving 11-35% and deans 58-94%. Post-Covid-19, real faculty pay has fallen more than in comparable fields and the sensitivity of pay to research performance has weakened.

That is from a new paper by Michelle Lowry, Daniel Bradley, April M. Knill, and Jared Williams. Via Arpit Gupta.

*How to be a Public Ambassador for Science*

The subtitle is The Scientist as Public Intellectual, and the author is my very good friend Jim Olds, who works at George Mason University. A very timely topic, here is one excerpt:

I was only about eight weeks into my new job. I’d been sworn in and found myself very much thrown into the pool’s deep end. First, the job was much more than serving as the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) lead for President Obama’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) project. Second, the learning curve was very steep. There were meetings full of acronyms that meant nothing to me. And these were my meetings — with my direct reports. I had learned the hard way that the Eisenhower Conference Center in the White House complex was made of steel and acted like a Faraday cage: cell phones didn’t work there. Tuesdays started with breakfast at 7:30 a.m. and went straight through for 12 hours with meeting after meeting.

Recommended, most of all informative about the NSF and also neuroscience.

Resources for Teaching Tariffs

Trump has put tariffs on the economics agenda in a way that hasn’t been true for decades. As a new semester of principles of economics begins, here are some resources for teaching tariffs.

Comparative Advantage (video)

The Microeconomics of Tariffs and Protectionism (video)

Why Do Domestic Prices Rise with Tariffs? (post)

Trade Diversion (Why Tariffs on More Countries Can Be Better) (post)

Manufacturing and Trade (post), Manufacturing Went South (post) and Tariffs Hurt Manufacturing (post)

Three Simple Rules of Trade Policy (Lerner symmetry, imports are inputs, trade balances and capital flows; post)

Tariffs and Taxes (post), Tariffs are a Terrible Way to Raise Revenue (Albrecht post) and Consistency on Tariffs and Taxes (post)

Globalization: Economics, Culture and the Future (video)

The Tariff Tracker, great source for real time tracking of prices such as below (the data can be downloaded):

![]()

Singapore’s Pay Model Isn’t India’s: Market Wages vs. Civil-Service Rents

In my post How High Government Pay Wastes Talent and Drains Productivity I pointed to evidence that high government compensation in poorer countries creates tremendous waste and drains the private sector of productive talent. A reader asked: What about Singapore?—famous for paying its top officials very well.

Singapore, however, is hardly comparable to India. Its GDP per capita is about 37 times India’s (~$91k vs. $2.4k) and its population is ~1/233rd the size (6m vs. 1.4b). Still, lets take a closer look.

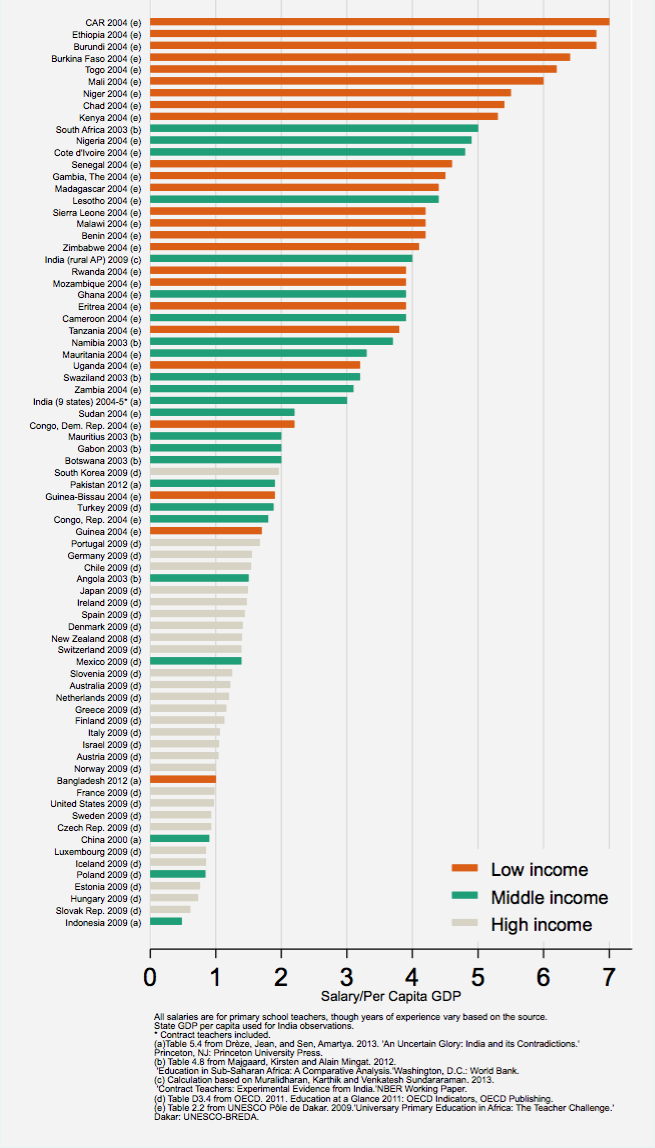

When I discuss high public pay in places like India, Greece, or Brazil, I don’t mean a few top ministers. I mean millions of railway clerks, office staff, and civil servants. Teachers illustrate the point well, since their work is broadly similar worldwide. As Justin Sandefur shows in the data at right, teacher salaries relative to GDP per capita tend to be highest in the poorest countries—sometimes five times GDP per capita or more.

Sandefur comments:

This may come as a bit of a surprise to many rich-country readers. There’s no doubt that teachers in, say, India earn much less than teachers in Ireland, but relative to context, they tend to be very well paid. Dividing by per capita GDP is a rough and ready way to put salaries in context.

The evidence suggests supply and demand can’t explain this. For example, in countries where teachers are highly paid relative to GDP per capita, they’re also paid far above private-sector wages for the same job. Sandefur presents more evidence on this question and concludes:

…Public school teachers in many developing countries earn civil service salaries that are far higher than market wages. This is what economists traditionally refer to as “rents.”

Singapore does NOT fit this pattern. Its teachers earn on the order of 70–80% of GDP per capita, market wages, not inflated packages. What’s unusual in Singapore is only at the top: a small number (fewer than 500) of elite officials and politicians have salaries pegged to the highest 1,000 Singapore-citizen income earners.

The issue Singapore is tackling is wage compression. In many democracies, collective bargaining combined with fairness, envy and inequality concerns pushes pay up at the bottom and down at the top. Denmark and heavily unionized firms are classic cases. Singapore, meritocratic and unapologetic, instead says its highest-ranking officials should be paid like CEOs.

Unlike India, Italy, Greece or Brazil, Singapore’s policy is not to pay any government workers above market wages but to pay competitive salaries to its entire civil service, even those at the top. Crucially, Singapore does not use mass exams to limit entry–it doesn’t have to because by keeping wages consistent with similar jobs in the private sector it matches supply to demand. As a result, we do not see in Singapore thousands or even millions of over-qualified people applying for a handful of over-paid government jobs, as in this example from Italy (quoted in Geromichalos and Kospentaris):

Italy’s chronic unemployment problem has been thrown into sharp relief after 85,000 people applied for 30 jobs at a bank [. . . ] The work is not glamorous – one duty is feeding cash into machines that can distinguish banknotes that are counterfeit or so worn out that they should no longer be in circulation. The Bank of Italy whittled down the applicants to a “shortlist” of 8,000, all of them first-class graduates with a solid academic record behind them. They will have to sit a gruelling examination in which they will be tested on statistics, mathematics, economics and English [. . . ] The high level of interest was a reflection of the state of the economy but also of the Italian obsession with securing “un posto fisso” – a permanent job.

So far from being a counter-example, Singapore illustrates the lesson: Singapore pays market wages, not rents—thereby avoiding the rent-seeking and talent misallocation that plague countries where civil servants are paid far above their market value.

My biographical podcast with Joshua Rosen

Joshua writes me:

It came out great.

Here it is on Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/formative-figures/id1809832335?i=1000723588104

Here it is on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5q5rnjcQTLASL438hI6s3c?si=YWB2sduVRmiCV0TUrSRSHg

Lots of fun for me, mostly tales of childhood and the like.

India, Greece, Brazil: How High Government Pay Wastes Talent and Drains Productivity

Compensation for government jobs is higher relative to GDP per capita the poorer the country. In other words, government workers are most overpaid in poor countries. Excessive public-sector compensation in low- and middle-income countries distorts labor markets on two margins: queues (rent-seeking to win jobs) and misallocation (talent and taxes diverted from the private sector).

In my two posts Massive Rent-Seeking in India’s Government Job Examination System and The Tragedy of India’s Government-Job Prep Towns I drew attention to the first margin, rent-seeking losses from the queues. India’s most educated young people—precisely those it needs in the workforce—often devote years of their life cramming for government exams instead of working productively. These exams cultivate no real-world skills and entire towns have become specialized in exam preparation. I argued using a back-of-the-envelope calculation that the rent seeking losses alone could easily be on the order of 1.4% of GDP annually. More tragically, large numbers of educated young people are inevitably disillusioned. Finally, because pay is so high, the state can’t staff up; India has all the laws of a rich country with roughly one‑fifth the civil servants per capita.

Two macro papers quantify the other margin of loss: who ends up where.

In The unintended consequences of meritocratic government hiring, Geromichalos and Kospentaris (GK) look at the consequences of excessively high government salaries in Greece. In (MIS)Allocation Effects of an Overpaid Public Sector, Cavalcanti and Santos look at the case of Brazil. Both papers model the allocation of labor between the private and public sectors and focus on the cost of drawing too many high-productivity workers into government jobs.

GK summarize their results for Greece:

In many countries, public employees enjoy considerable job security and generous compensation schemes; as a result, many talented workers choose to work for the public sector, which deprives the private sector of productive potential employees. This, in turn, reduces firms’ incentives to create jobs, increases unemployment, and lowers GDP…. [Calibrating the model to Greece] we find that a 10% drop in public sector wages results in a 3.8% increase in private sector’s productivity, a 7.3% drop in unemployment, and a 1.3% increase in GDP.

CS report similar distortions in Brazil:

Our counterfactual exercises demonstrate that public–private earnings premium can generate important allocation effects and sizeable productivity losses. For instance, a reform that would decrease the public–private wage premium from its benchmark value of 19% to 15% and would align the pension of public sector workers with the one in place for private sector workers could increase aggregate output by 11.2% in the long run without any decrease in the supply of public infrastructure.

Interestingly, in the GK model there is no rent-seeking waste because workers are assumed to forecast exam outcomes perfectly and sort directly into private or public streams. In my India model, by contrast, the waste comes precisely from the years of futile exam preparation. GK also find that reducing the number of public jobs can raise efficiency, while my take is that in India high salaries make the public sector paradoxically too small (thus to some extent limiting misallocation). CS also focus on allocation but, unlike GK, they estimate that rent-seeking losses are massive—about triple my conservative estimate:

The aggregate cost of job applications to public jobs, which we label as the rent seeking cost, is large in the baseline economy…roughly 3.61 percent of output.

Across India, Greece, and Brazil the story converges: overpaying government workers distorts education, job search, and firm dynamics. The waste shows up as socially unproductive effort devoted to entering the echelons of government employment and a private sector which is drained of top talent causing it to be less productive and to grow more slowly. In short, rent seeking and misallocation from overly generous government compensation generate large macroeconomic losses. As relative compensation tends to be higher the poorer the economy, high government pay can be a development trap.

What should I ask John Amaechi?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is Wikipedia on John:

John Uzoma Ekwugha Amaechi // ⓘ, OBE (/əˈmeɪtʃi/; born 26 November 1970) is an English psychologist, consultant and former professional basketball player. He played college basketball for the Vanderbilt Commodores and Penn State Nittany Lions, and professional basketball in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Amaechi also played in France, Greece, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Since retiring from basketball, Amaechi has worked as a psychologist and consultant, establishing his company Amaechi Performance Systems.

In February 2007, Amaechi became the first former NBA player to publicly come out as gay after doing so in his memoir Man in the Middle.

John has a new book coming out, namely It’s Not Magic: The Ordinary Skills of Exceptional Leaders. So what should I ask him?

Who gets into the best colleges and why?

We use anonymized admissions data from several colleges linked to income tax records and SAT and ACT test scores to study the determinants and causal effects of attending Ivy-Plus colleges (Ivy League, Stanford, MIT, Duke, and Chicago). Children from families in the top 1% are more than twice as likely to attend an Ivy-Plus college as those from middle-class families with comparable SAT/ACT scores. Two-thirds of this gap is due to higher admissions rates for students with comparable test scores from high-income families; the remaining third is due to differences in rates of application and matriculation. In contrast, children from high-income families have no admissions advantage at flagship public colleges. The high-income admissions advantage at Ivy-Plus colleges is driven by three factors: (1) preferences for children of alumni, (2) weight placed on non-academic credentials, and (3) athletic recruitment. Using a new research design that isolates idiosyncratic variation in admissions decisions for waitlisted applicants, we show that attending an Ivy-Plus college instead of the average flagship public college increases students’ chances of reaching the top 1% of the earnings distribution by 50%, nearly doubles their chances of attending an elite graduate school, and almost triples their chances of working at a prestigious firm. The three factors that give children from high-income families an admissions advantage are uncorrelated or negatively correlated with post-college outcomes, whereas academic credentials such as SAT/ACT scores are highly predictive of post-college success.

That is from a new paper by Raj Chetty, David J. Deming, and John N. Friedman. One immediate conclusion is that standardized test scores help lower-income groups get into the best schools, compared to the alternatives.