Category: History

Estimating when the Soviets could produce a nuclear weapon

Following up on Alex's post on Soviet economic growth forecasts, I was intrigued to read the 1940s estimates, emanating from the United States, about when the Soviets would obtain a nuclear weapon. Leslie Groves — who knew something about building a bomb — testified in front of Congress that it would take them twenty years. In 1948 many Kremlinologists were saying "five to ten years," when in fact the Soviets had a usable bomb in 1949. In 1948 an engineer in Look magazine predicted the Soviets would get the bomb in 1954. Many scientists predicted 1952 and some thought 1970. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were predicted the mid- to late 1950s. The Air Force was the one institution which got it right and remarks from Senator Arthur Vandenberg were close to the truth as well.

Groves was skeptical of the Soviet engineers, who did not turn out to cause delays and who regularly did very well with what they had to work with. Other commentators did not realize that 40 percent of the world's known uranium reserves were within the Soviet Union, or that the Soviets could use German uranium quite well.

All this is from the truly excellent new book Red Cloud at Dawn: Truman, Stalin, and the End of the Atomic Monopoly, by Michael D. Gordin. Here is one very accurate review of the book.

One question is what kind of ideological biases, if any, colored these forecasts. Another question is whether today's estimates of Iranian production are any better.

Thai-Cambodia refugee camps, 1975-1999

Study this model and try to improve on it. Here is further historical information.

What does the domestic U.S. political equilibrium look like when we are funding and running these camps? Will Obama be seen as "doing too much" for "black people"? How will we punish wrongdoers in the camps? Will the residents be treated better than those in Guantanamo? What happens when we, explicitly or implicitly, start using Haitian gangs to keep order in the camps? How many Haitians will the DR shoot crossing the border?

Haitians are extremely nationalistic, sensitive to foreign influence, and they have a clear historical memory of the U.S. occupation of 1915-1934. What if they ask us to leave before the camps are self-sustaining? For how long will we pretend that Haiti still has a real government?

Those are my questions for today.

Why is Haiti so poor?, part II

Here is a short essay, I thank MR commentator Bobabdil for the pointer.

Why is Haiti so poor?

I'm not interested in talking about Greg Clark or making comparisons to the West; if need be compare it to other black Caribbean nations, such as Jamaica or Barbados. It's much worse and in terms of social indicators it is also worse than many places in Africa. Why? Here a few hypotheses (NB: I don't endorse all of them):

1. Haiti cut its colonial ties too early, rebelling against the French in the early 19th century and achieving complete independence. Guadaloupe and Martinique are still riding the gravy train and French aid is a huge chunk of their gdps.

2. Haiti was a French colony in the first place and French colonies do less well.

3. Sugar cane gave Haiti some early characteristics of "the resource curse," dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries.

4. Haiti was doing OK until the Duvaliers destroyed civil society, thus putting the country on a path toward destruction. It is a more or less random one-time event which wrecked the place.

5. Hegel was correct that the "voodoo religion," with its intransitive power relations among the gods, was prone to producing political intransitivity as well. (Isn't that a startling insight for a guy who didn't travel the broader world much?)

6. For reasons peculiar to the history of the slave trade, Haitian slaves came from many different parts of Africa and thus Haitian internal culture has long had lower levels of cohesion and cooperation. (The former point about the mix is true, but the cultural point is speculation.)

7. Haiti has higher than average levels of polygamy (but is this cause or effect?)

8. In the early to mid twentieth century, Haiti was poorly situated to attract Chinese and other immigrants, unlike say Jamaica or Trinidad. It is interesting that many of the wealthiest families in Haiti are Lebanese, such as the Naders.

Overall I don't find this set of possible factors very satisfactory. Is it asking too much to wish for an economics profession that is obsessed with such a question?

If you are looking for some cross-sectional variation to ponder, consider the fate of Haitians in Suriname (they make up a big chunk of the population there), Haiti vs. Santiago, Cuba, pre-Castro of course, or why early Haitian migrants to Montreal have done better than later migrants to Miami and Brooklyn.

Prison protectionism

State officials admited that the prison was built in an isolated location to avoid competition "with the honest mechanical classes."

That's about Clinton State Prison, built in 1845 and the anecdote is from Timothy Gilfoyle's A Pickpocket's Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. Here is my previous post on the book.

Large industrial enterprises in the late 19th century

By the time of Appo's first incarceration in 1874, Sing Sing was a sprawling, seventy-seven-acre industrial complex, simultaneously a "great human cage" and "a leviathan" factory complex…Inside, horses and wagons moved higher and thither, ship masts towered above the quay walls, and freight trains thundered through the prison grounds. In the age of industry, wrote another observer, Sing Sing was a "vast creative emporium." It was arguably the largest manufacturing complex in the country, if not the world.

The size of Sing Sing's labor force dwarfed those of most American factories.

That's from Timothy Gilfoyle's excellent A Pickpocket's Tale: The Underworld of Nineteenth Century New York.

The Pamuk brothers

Kurt Schuler writes to me:

If you are not already aware of it (and I didn’t see it mentioned in a quick search of Marginal Revolution), it may interest you that Orhun Pamuk has an older brother, Sevket, an economist who shuttles between LSE and Bogaziçi (Bosphorus) University in Istanbul. Sevket is the coauthor of A History of Middle East Economies in the Twentieth Century and author of A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire, among other works in English and Turkish…A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire is a really good book for those interested in monetary history, by the way, because it covers a long period, a big geographical area, and a body of writing in languages that hardly any Anglophone economists read, all in a brisk 300 pages.

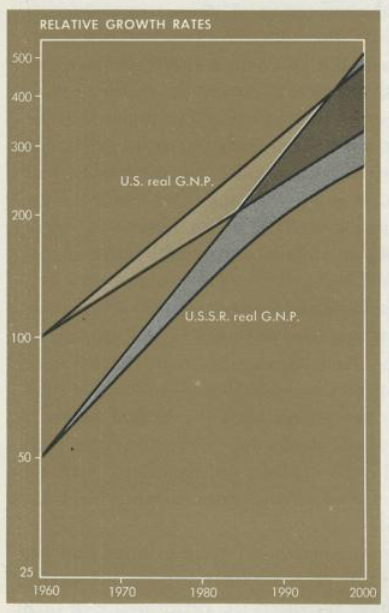

Soviet Growth & American Textbooks

In the 1961 edition of his famous textbook of economic principles, Paul Samuelson wrote that GNP in the Soviet Union was about half that in the United States but the Soviet Union was growing faster. As a result, one could comfortably forecast that Soviet GNP would exceed that of the United States by as early as 1984 or perhaps by as late as 1997 and in any event Soviet GNP would greatly catch-up to U.S. GNP. A poor forecast–but it gets worse because in subsequent editions Samuelson presented the same analysis again and again except the overtaking time was always pushed further into the future so by 1980 the dates were 2002 to 2012. In subsequent editions, Samuelson provided no acknowledgment of his past failure to predict and little commentary beyond remarks about “bad weather” in the Soviet Union (see Levy and Peart for more details).

Among libertarians, this story has long been the subject of much informal amusement. But more recently my colleague David Levy and co-author Sandra Peart have discovered that the story is much more interesting and important than many people, including myself, had ever realized.

Among libertarians, this story has long been the subject of much informal amusement. But more recently my colleague David Levy and co-author Sandra Peart have discovered that the story is much more interesting and important than many people, including myself, had ever realized.

First, an even more off-course analysis can also be found in another mega-selling textbook, McConnell’s Economics (still a huge seller today). Like Samuelson, McConnell estimated Soviet GNP as half that of the United States in 1963 but he showed that the Soviets were investing a much larger share of GNP and thus growing at rates “two to three times” higher than the U.S. Indeed, through at least ten (!) editions, the Soviets continued to grow faster than the U.S. and yet in McConnell’s 1990 edition Soviet GNP was still half that of the United States!

A second case of being blinded by “liberal” ideology? If so, Levy and Peart throw another curve-ball because the very liberal even “leftist” texts of the time, notably those by Lorie Tarshis and Robert Heilbroner did not make the Samuelson-McConnell mistake.

Tarshis and Heilbroner were more liberal than Samuelson and McConnell but offered a more nuanced, descriptive and tentative account of the Soviet economy. Why? Levy and Peart argue that they were saved from error not by skepticism about the Soviet Union per se but rather by skepticism about the power of simple economic theories to fully describe the world in the absence of rich institutional detail.

To make their predictions, Samuelson and McConnell relied heavily on the production possibilities frontier (PPF), the idea that the fundamental tradeoff for any society was between “guns and butter.” Thus, in the 1948 edition Samuelson wrote:

The Russians having no unemployment before the war, were already on their Production-possibilities curve. They had no choice but to substitute war goods for civilian production-with consequent privation.

Note that Samuelson assumes all countries and economic systems are efficient (the Russians are “on” the curve) only the choice of guns versus butter differs. When the war ended, the fundamental tradeoff became one between investment and consumption and since the Soviets invested a greater share of GNP they would naturally consume less but grow faster. Moreover, since the Soviet’s had solved the unemployment problem they were, if anything, more efficient than the U.S. (here we see the Keynesian influence).

Levy and Peart conclude that although ideology may have played a role what arguably made a bigger difference was the blindness imposed by chosen tools. As they write:

We are all constrained by means of models: we gain insight in one dimension by blinding ourselves to events in other dimensions. Competition among models may be necessary to insure that the benefits of the models exceeds their cost.

(Applications to the financial crisis are apposite.)

Addendum: Bryan Caplan also comments. As Bryan notes, a very good economist can use PPFs and still get the story right.

“Fruitful Decade for Many in the World”

My NYT column today is about how good the last ten years have been for China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, and much of Africa. It is not, as Time magazine has suggested, the worst decade in human history. Here is a brief excerpt:

One lesson from all of this is that steady economic growth is an underreported news story – and to our own detriment. As human beings, we are prone to focus on very dramatic, visible events, such as confrontations with political enemies or the personal qualities of leaders, whether good or bad. We turn information about politics and economics into stories of good guys versus bad guys and identify progress with the triumph of the good guys. In the process, it’s easy to neglect the underlying forces that improve life in small, hard-to-observe ways, culminating in important changes.

Here is Alex's earlier post on African success in the decade. In addition to growth statistics, I see much of the developing world as having demonstrated a much higher than expected level of social and political cohesion. Excerpt:

Since 2007, according to Goldman Sachs, the biggest emerging markets–Brazil, Russia, India and China–have accounted for 45% of global growth, almost twice as much as in 2000-06 and three times as much as in the 1990s.

Arnold Kling notes: "Even in the United States, the fact that people are living healthier longer represents an improvement above and beyond the GDP statistics."

I did not have enough space to discuss the question of growth rates versus per capita growth rates, but here are a few relevant points:

1. Babies are pretty cheap to feed. In the short run, if your economy grows, and at the same time produces more infants, the adults are still better off.

2. In the longer run, developing countries are making the "demographic transition" quicker and more dramatically than had been expected. Mexico is an extreme example of this more general point. So if you are very worried about overpopulation (not my view), there still has been plenty of good demographic news in the last decade. Economic growth in the developing world will not be "swallowed up" by rising population.

3. "More children" can be a legitimate way for a country to enjoy higher living standards.

4. Social indicators such as water and sanitation in households are generally higher in the afore-cited countries, over the last decade. That's further evidence for #1.

Again, I'd like to stress the general point that most American-born economists are not sufficiently cosmopolitan in their thinking and writing.

Projects to ponder, and let’s drink a toast to fixed costs for once

Hans Larsson, the Canada Research Chair in Macro Evolution at

Montreal's McGill University, said he aims to develop dinosaur traits

that disappeared millions of years ago in birds.Larsson believes by flipping certain genetic levers during a chicken

embryo's development, he can reproduce the dinosaur anatomy, he told

AFP in an interview.Though still in its infancy, the research could eventually lead to

hatching live prehistoric animals, but Larsson said there are no plans

for that now, for ethical and practical reasons — a dinosaur hatchery

is "too large an enterprise."

The longer story is here and I thank Bookslut (one of my favorite blogs) for the pointer. Here is Larsson's home page.

How bad is it to be uninsured today?

Ezra Klein raised a big stir by suggesting that the possible failure of the health care bill will cost a large number of lives; he cited a figure of 20,000 per year. (You'll find pushback from Michael Cannon on the number.)

Rather than disputing the number, my question is a simpler one. Let's say the figure were a correct one. How would you fill in the following blank?:

"Being uninsured in 2009 is, in terms of life expectancy, as bad as being insured in the earlier year ????"

What is the correct year for this comparison to hold?

Simply knowing the correct year is my main concern in this post, but there is an additional angle. Twenty years from now there will also be some uninsured Americans, even if the current bill passes. There will be pleas to help them. If you wish to help them, does that mean that the insured today also deserve additional health care subsidies? Or is the whole comparison just about equality? How about caring about inequality across time? If you favor additional subsidies for the uninsured today, are you also committed to wishing there had been additional subsidies for the insured back in year ????

I thank Bryan Caplan for a useful conversation related to this blog post.

Not in a liquidity trap

Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, the former Rhodesia, was a quadrillion times worse than it was in Weimar Germany.

That's via Jason Kottke (source here). There's also this bit:

The cumulative devaluation of the Zimbabwe dollar was such that a stack of 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (26 zeros) two dollar bills (if they were printed) in the peak hyperinflation would have be needed to equal in value what a single original Zimbabwe two-dollar bill of 1978 had been worth. Such a pile of bills literally would be light years high, stretching from the Earth to the Andromeda Galaxy.

Nie pozwalam!

Liberum veto (Latin for I freely forbid) was a parliamentary device in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It allowed any member of the Sejm to force an immediate end to the current session and nullify all legislation already passed at it by shouting Nie pozwalam! (Polish: I do not allow!).

Here is more.

Another reason not to be a Civil War revisionist

As if you needed one:

Although southerners rebelled against growing centralization of the federal government, they had no qualms about establishing a strong national state of their own. Scholars have classified the Confederate central government as a form of "war socialism." The Confederacy owned key industries, regulated prices and wages, and instituted the most far-reaching draft in North American history. The Confederacy employed some 70,000 civilians in a massive (if poorly coordinated) bureaucracy that included thousands of tax assessors, tax collectors, and conscription agents. The police power of the Confederate state was sometimes staggering. To ride a train, for example, every passenger needed a special government pass…Political scientist Richard Franklin Bensel writes that "a central state as well organized and powerful as the Confederacy did not emerge until the New Deal and subsequent mobilization for World War II."

That is from John Majewski's excellent Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation.

One implication is that the United States kept "small government" for an artificially long period of time, due to North-South splits and the resulting inability to agree on what a larger government should be doing.

Project Cybersyn

Cybersyn was a project of the socialist government of Salvador Allende (1970-1973) and British cybernetic visionary Stafford Beer; its goal was to control the Chilean economy in real-time using computers and "cybernetic principles." The military regime that overthrew Allende dropped the project and probably for this reason when the project is periodically rediscovered it is often written about in a romantic tone as a revolutionary "socialist internet," decades ahead of its time that was "destroyed" by the military because it was "too egalitarian" or because they didn't understand it.

Although some sources at the time said the Chilean economy was "run by computer," the project was in reality a bit of a joke especially in retrospect, albeit a rather expensive one, and about the only thing about it that worked were the ordinary Western Union telex machines spread around the country. The two computers supposedly used to run the Chilean economy were IBM 360s (or machines on that order). These machines were no doubt very impressive to politicians and visionaries eager to use their technological might to control an economy (see picture at right.) Today, our perspective will perhaps be somewhat different when we realize that these behemoths were far less powerful than an iPhone. Run an economy with an iPhone? Sorry, there is no app for that.

Indeed, you don't have to read far between the lines of Andy "socialist internet" Beckett's account to get a flavor of what was really going on:

Beer's original band of disciples had been diluted by other, less idealistic scientists. There was constant friction between the two groups. Meanwhile, Beer himself started to focus on other schemes: using painters and folk singers to publicise the principles of high-tech socialism; testing his son's electrical public-opinion meters, which never actually saw service; and even organising anchovy-fishing expeditions to earn the government some desperately needed foreign currency.

(Note the classic, 'the visionary failed because others lacked idealism' story. Meanwhile the visionary is off on an anchovy-fishing expedition.)

Recently, Jeremiah Axelrod and Greg Borenstein have put together an excellent video essay (fyi, 25 minutes) which gets to the heart (perhaps head would be a better word) of Cybersyn by focusing on the legendary "control room," which they delightfully call the "inverted panopticon."

It is no accident, say Axelrod and Borenstein, that the control room looks like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise because the whole purpose of the room was to exude a science-fiction fantasy of omniscience and omnipotence. The fantasy naturally appealed to Allende who had the control room moved to the presidential palace just days before the coup.

The control room is like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise in another respect–both are stage sets. Nothing about the room is real, even the computer displays on the wall are simply hand drawn slides projected from the other side with Kodak carousels.

Ironically, when rumors of the project began to circulate, the illusion of omniscience and omnipotence that Beer had created, the same illusion that so appealed to Allende and that had funded Beer's visions and experiments, this illusion caused fear that an all-knowing big brother was on the way–and such fear may even have encouraged the coup.

After the coup, rather than destroying the project because of its "egalitarian" nature, the military regime was more likely to have been disillusioned and disappointed to discover project Cybersyn's impotence.

Hat tip to Boing Boing.