Category: Medicine

New York Will Try Convalescent Blood Therapy

On March 17 I wrote: “A simple and medically feasible strategy is available now for treating COVID-19 patients, transfuse blood plasma from recovered patients.” New York, with other states following closely behind, is now trying the idea.

NBC News: Hoping to stem the toll of the state’s surging coronavirus outbreak, New York health officials plan to begin collecting plasma from people who have recovered and injecting the antibody-rich fluid into patients still fighting the virus.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the plans during a news briefing Monday. The treatment, known as convalescent plasma, dates back centuries and was used during the flu epidemic of 1918 — in an era before modern vaccines and antiviral drugs.

Some experts say the treatment, although somewhat primitive, might be the best hope for combating the coronavirus until more sophisticated therapies can be developed, which could take several months.

The FDA acted quickly to approve the therapy on an emergency case-by-case basis, although it’s not clear to me that legally they should be involved at all given the therapy seems more like an off-label use of blood plasma than a new drug.

Suggest regulatory pauses

Suggest Regulatory Pauses

Is there some government regulation or rule that is keeping you from helping manage the COVID-19 crisis?

Maybe you’re a frontline healthcare worker, an administrator, or work in manufacturing, and believe you could make medical supplies. Whatever your position or industry, perhaps you have ideas that could help.

We want to hear from you. Please fill out the form below.

An initiative from the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago.

FDA Stops At-Home Tests

TechCrunch…the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has updated its Emergency Use Authorization guidelines to private labs that specifically bar the use of at-home sample collection. This means startups, including Everlywell, Carbon Health and Nurx, will have to immediately discontinue their testing programs in light of the clarified rules.

The FDA issued the updated guidance on March 21, and though some of the companies had already begun to ship their sample collection kits to people, and even begun to receive samples back to their diagnostic laboratory partners, even any samples in-hand will not be tested, and will instead be destroyed in order to comply with the FDA’s request

The tests are collected at home but the tests themselves are done in certified labs under quality-control standards (CLIA). It is of course possible, even likely, that tests collected at home are not as accurate as those collected by a trained nurse. But we don’t want trained nurses to be testing everyone–they have other things to do right now. Furthermore, some of these errors will be detected at the lab and can be fixed with a retest. False negatives are possible but going to a hospital or standing in line to get a test also comes with risk. False negatives will also become apparent to the extent that symptoms worsen at which time patients can seek medical assistance. Yes, of course, delay and false reassurance are also not without risk. Welcome to the world of tradeoffs. But at this point in time we need to unleash American ingenuity and enterprise and evolve our way to the frontier as conditions improve.

We need to learn now, regulate later.

Lessons from the “Spanish Flu” for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity

That is the subtitle of a new paper by Robert J. Barro, José F. Ursúa, and Joanna Weng, here is the abstract:

Mortality and economic contraction during the 1918-1920 Great Influenza Pandemic provide plausible upper bounds for outcomes under the coronavirus (COVID-19). Data for 43 countries imply flu-related deaths in 1918-1920 of 39 million, 2.0 percent of world population, implying 150 million deaths when applied to current population. Regressions with annual information on flu deaths 1918-1920 and war deaths during WWI imply flu-generated economic declines for GDP and consumption in the typical country of 6 and 8 percent, respectively. There is also some evidence that higher flu death rates decreased realized real returns on stocks and, especially, on short-term government bills.

I wonder if the economic cost isn’t higher today because we know more about how to limit pandemic spread and we also value human lives more, relative to economic output?

Kudos to the authors for such swift work.

Also from NBER here is Andrew Atkeson on the dynamics of disease progression, depending on the percentage of the population with the disease. Here is an excerpt from the paper:

Even under severe social distancing scenarios, it is likely that the health system will be overwhelmed, which is indicated to happen when the portion of the U.S. population actively infected and suffering from the disease reaches 1% (about 3.3 million current cases).7 More severe mitigation efforts do push the date at which this happens back from 6 months from now to 12 months from now or more, perhaps allowing time to invest heavily in the resources needed to care for the sick. It is clear that to avoid a health care catastrophe as is currently being experienced in Italy, prolonged severe social distancing measures will need to be combined with a massive investment in health care capacity.

Under almost all of the scenarios considered, at the peak of the disease progression, between 10% and 20% of the population (33 – 66 million people) suffers from an active infection at the same time.

A not entirely cheery prognosis.

A new idea for small business lending and support

From my email, from Amanda Brown, she is developing this plan with Ben Laufer:

I am a master’s student at Stanford in Management Science & Engineering and a fan of your blog Marginal Revolution. I have been following it more closely in the midst of COVID-19, especially the conversations about small business financing during the crisis (e.g. today’s post about bridge loans).

I was hoping to get feedback on an idea for a new small business lending platform which would allow community members to fund fractional amounts of a business loan. The thesis is that fractional loan contributions from local supporters would give institutional lenders confidence to fund the full requested loan amount (and that the total amount contributed by peers would supplement traditional measures of borrower creditworthiness, such as FICO score, cash flow, etc., when setting the interest rate). For example, 10% of the principal might come from all the peer investors combined, and the remaining 90% from a single big lender. To my knowledge, nothing quite like this exists. In the wake of COVID-19 shutdowns, it seems especially important for small businesses at the heart of our communities to be getting access to low-interest financing based on peer endorsement.

Adding the “peer staking” element to a small business loan signals to investors that the local community believes in the future success of the business and the borrower’s likelihood of repaying (and peers would also be able to earn the same interest rate return on the principal as the majority funder… so it’s not like crowdfunding, where you contribute but won’t see your dollar again…). The design also increases accountability without the need for a collateral since borrowers would feel a personal responsibility to repay their peer debt-holders, who may be friends, family or customers.

I am wondering what your thoughts are on the idea (and its relevance at this time). If you think it is worthwhile, perhaps you would consider sharing this 5-minute survey with your followers to collect feedback on the idea:

https://forms.gle/Tk2Gweqa5frTacid9

Amanda Brown ([email protected])

Ben Laufer ([email protected])

Pooling to multiply SARS-CoV-2 testing throughput

Here is an email from Kevin Patrick Mahaffey, and I would like to hear your views on whether this makes sense:

One question I don’t hear being asked: Can we use pooling to repeatedly test the entire labor force at low cost with limited SARS-CoV-2 testing supplies?

Pooling is a technique used elsewhere in pathogen detection where multiple samples (e.g. nasal swabs) are combined (perhaps after the RNA extraction step of RT-qPCR) and run as one assay. A negative result confirms no infection of the entire pool, but a positive result indicates “one or more of the pool is infected.” If this is the case, then each individual in the pool can receive their own test (or, if we’re getting fancy [read: probably too hard to implement in the real world], perform an efficient search of the space using sub-pools).

To me, at least, the key questions seem to be:

– Are current assays sensitive enough to work? Technion researchers report yes in a pool as large as 60.

– Can we align limiting factors in testing cost/velocity with pooled steps? For example, if nasal swabs are the limiting reagent, then pooling doesn’t help; however if PCR primers and probes are limiting it’s great.

– Can we get a regulatory allowance for this? Perhaps the hardest step.Example (readers, please check my back-of-the-envelope math): If we assume base infection rate of the population is 1%, then pooling of 11 samples has a ~10% chance of coming out positive. If you run all positive pools through individual assays, the expected number of tests per person is 0.196 or a 5.1x multiple on testing throughput (and a 5.1x reduction in cost). This is a big deal.

If we look at this from the view of whole-population biosurveillance after the outbreak period is over and we have a 0.1% base infection rate, pools of 32 samples have an expected number of tests per person at 0.0628 or a 15.9x multiple on throughput/cost reduction.

Putting prices on this, an initial whole-US screen at 1% rate would require about 64M tests. Afterward, performing periodic biosurveillance to find hot spots requires about 21M tests per whole-population screen. At $10/assay (what some folks working on in-field RT-qPCR tests believe marginal cost could be), this is orders of magnitude less expensive than mitigations that deal with a closed economy for any extended period of time.

I’m neither a policy nor medical expert, so perhaps I’m missing something big here. Is there really $20 on the ground or [something something] efficient market?

By the way, Iceland is testing many people and trying to build up representative samples.

That was then, this is now

In 1957, when flu swept through Hong Kong, Mr [Maurice] Hilleman identified the virus as a new form to which people had no natural immunity and passed on his findings to vaccine-makers. When the virus reached the United States a few months later 40m doses of vaccine were ready to limit its damage.

Here is more from The Economist, circa 2005, via Brian LaRocca. How many of you have heard of Maurice Hilleman? He has other accomplishments, and according to Wikipedia “He is credited with saving more lives than any other medical scientist of the 20th century.” I say he is underrated!

The Internal Contradictions of Segregating the Elderly

There are two problems, even internal contradictions, with segregating the elderly and letting others return to work. The first is fairly well known. When you run the numbers, as the British did, you find that a lot of young people would die. If we return to work too quickly it could easily happen that 20-40% of the US population gets COVID-19. Suppose 20% of the population gets it–that’s 66 million people. And let’s suppose the death rate is on the low end because healthy, young people get it rather than the elderly, say half of one percent, .005, then we have 330,000 deaths of healthy, young people.

Moreover, the numbers I just gave are conservative and don’t make a lot of sense because if 330,000 die then the hospital system is going to be overwhelmed and the death rate will be higher than .005. An internal contradiction.

The second internal contradiction is less well known. We probably can’t segregate the elderly because the more young people get COVID-19 the less realistic protecting a subset of the population becomes. In other words, the premise of the segregation argument is that we can protect the elderly but that premise becomes less plausible the more COVID-19 spreads but allowing it to spread is why we were locking down the elderly. An internal contradiction.

Are there some scenarios where all this works out? Probably but I wouldn’t bet on hitting the trifecta. The lesson of COVID-19 is that like it or not we are all in this together.

Arguments Against International Trade in Modern Principles of Economics

In our textbook, Modern Principles of Economics, Tyler and I explain the benefits of free trade and show why some common arguments against free trade are mistaken. Our goal, however, is to teach students how to think like economists and so we also explain the costs of free trade. In particular, we indicate the strongest arguments against free trade and explore when those arguments best apply. Here’s one of the better arguments against free trade, straight from the book:

If a good is vital for national security but domestic producers have higher costs than foreign producers, it can make sense for the government to tax imports or subsidize the production of the domestic industry. It may make sense, for example, to support a domestic vaccine industry. In 1918, more than a quarter of the U.S. population got sick with the flu and more than 500,000 died, sometimes within hours of being infected. The young were especially hard-hit and, as a result, life expectancy in the United States dropped by 10 years. No place in the world was safe, as between 2.5% and 5% of the entire world population died from the flu between 1918 and 1920. Producing flu vaccine requires an elaborate process in which robots inject hundreds of millions of eggs with flu viruses. In an ordinary year, there are few problems with buying vaccine produced in another country, but if something like the 1918 flu swept the world again, it would be wise to have significant vaccine production capacity in the United States.

If I may be permitted to advertise a bit (more). In Modern Principles, we explain the concept of externalities using flu shots. In macroeconomics, we deal with both real shocks and demand shocks and we list pandemics as one example of a real shock. We also explain how shocks are amplified and can create dis-coordination. These relevant, real world examples in Modern Principles are not an accident. There are different styles of textbooks. Some are written in a vanilla style so they don’t need to be updated or revised very often. In contrast, we wanted Modern Principles to have modern examples and to be relevant to the times. Sometimes, however, we’d like it to be a little less relevant.

Bridge loans for economically troubled firms

Andrew Ross Sorkin explains (NYT):

The fix: The government could offer every American business, large and small, and every self-employed — and gig — worker a no-interest “bridge loan” guaranteed for the duration of the crisis to be paid back over a five-year period. The only condition of the loan to businesses would be that companies continue to employ at least 90 percent of their work force at the same wage that they did before the crisis. And it would be retroactive, so any workers who have been laid off in the past two weeks because of the crisis would be reinstated.

Strain and Hubbard call for $1.2 trillion in lending to smaller businesses (Bloomberg). John Cochrane considers a version of the plan. Here is Brunnermeier, Landau, Pagano, and Reis. I have been pondering the following points:

1. If you are an optimist about the cycle of recovery, this is very likely a good idea. If you let those companies fall apart, there is a significant loss of organizational capital and the matching problems in the labor markets have to be solved all over again. Recent experience on that front is not so encouraging.

2. If you are a pessimist about the cycle of recovery, I am less sure how well this will work. Let’s say a vaccine is difficult and there a few waves of the virus. Many of the smaller or even larger businesses may be going under anyway, as they cannot live off aid forever. In the meantime, you might actually want those resources to be reallocated to good transport, biomedical testing, and so on. If the wartime analogy is apt, you don’t want to freeze the previous capital structure into place, unless of course you get lucky and win the war early.

3. If you a pessimist about the solvency of banks (have you ever seen a stress test for 30% unemployment?), you have not gotten the government out of the business of capital allocation.

4. The bridge loans might work especially poorly for start-ups. Yes, StubHub or some company like that is around for the long run, and if the bridge loans can keep them up and running until concerts return, so much the better. But what about the eighty wanna-bees next in line, most of whom are likely to fail? Do they too get bridge loans? (Do note the ecosystem as a whole is yielding positive value.) The market itself chose the venture capital financing form for those entities, not debt. And yet now the government is stepping in and propping them up with debt, even though we know virtually all of them are likely to fail (even pre-coronavirus that was the case). You might think “well, we will know not to do that.” But on what legal basis would those other “likely to fail start-ups” be excluded from the bridge loans?

4b. Is it all about “banks decide”? How do we stop banks from simply hoarding the new money? (The Fed already has flooded the banking system with liquidity.) Just loaning the money to super-safe firms for de facto negative rates? What exactly are the regulatory requirements here? To the extent the loans are de facto guaranteed, won’t banks lend to a large number of lemons? What do the interest rates and collateral requirements look like on these loans and how are those set in what is now a non-competitive setting?

5. Overall my sense is that American policy, if only for cultural reasons, has to proceed on an optimistic basis. It is not clear what the relevant alternative is, and I do not oppose bridge loans. Nonetheless I am seeing too many people jump uncritically at bridge loans with a “throw everything at the wall” approach and not thinking hard enough about their possible downsides. At the very least, being critical about bridge loans will help us make bridge loans better.

6. No, I don’t favor governmental bridge loans for non-profits. De facto, that this means this is a huge relative shift of resources away from non-profits and toward businesses. YMMV.

7. I have received numerous reader emails telling me how bad, slow, and cumbersome is the Small Business Administration process for getting loans. Will this new regime do better?

8. It is the same government that could not organize testing and mask production that we are expecting to run what might amount to a $1 trillion plus bridge loans program.

Have a nice day.

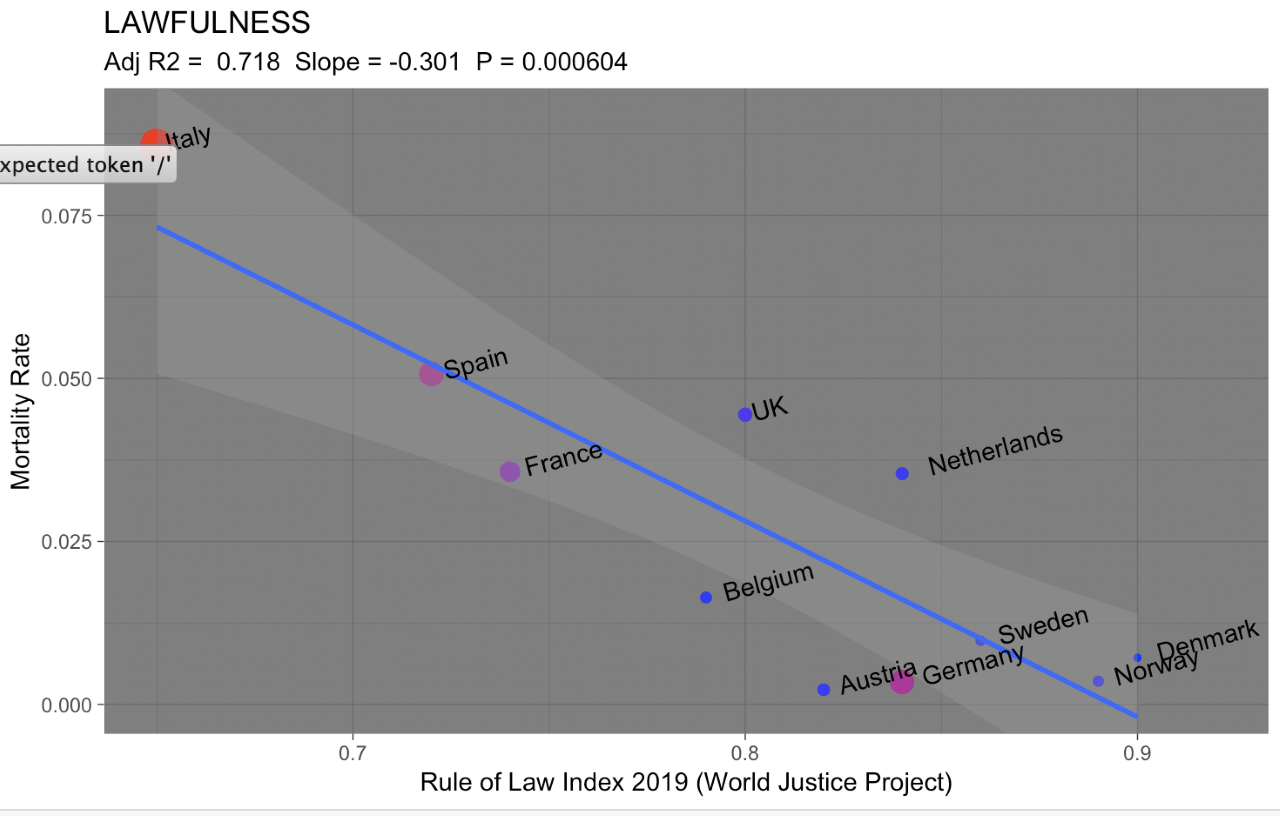

European fatality rates and lawfulness

Correlation ain’t causation, but nonetheless it is worth looking at correlation:

Via Daniel Wilson. And here is a story about defiant Iranians.

The three ideas you all are writing me the most about

1. Segregating old people, and letting others go about their regular business. Given how many older people now work (and vote), and how many employees in nursing homes are young, I’ve yet to see a good version of this plan, but if you favor it please do try to write one up. One of you suggested taking everyone over the age of 65 and encasing them in bubble wrap, or something.

2. Tracking and surveillance by smart phones. Here is one story, here is another. Here is an Oxford project. Singapore is using related ideas, China has too.

3. Testing as many Americans as possible, or at least a representative sample, to get data.

I hope to analyze these more in the future.

Emergent Ventures prize winners for coronavirus work

I am happy to announce the first cohort of Emergent Ventures prize winners for their work fighting the coronavirus. Here is a repeat of the original prize announcement, and one week or so later I am delighted there are four strong winners, with likely some others on the way. Again, this part of Emergent Ventures comes to you courtesy of the Mercatus Center and George Mason University. Here is the list of winners:

Social leadership prize: Helen Chu and her team at the University of Washington. Here is a NYT article about Helen Chu’s work, excerpt:

Dr. Helen Y. Chu, an infectious disease expert in Seattle, knew that the United States did not have much time…

As luck would have it, Dr. Chu had a way to monitor the region. For months, as part of a research project into the flu, she and a team of researchers had been collecting nasal swabs from residents experiencing symptoms throughout the Puget Sound region.

To repurpose the tests for monitoring the coronavirus, they would need the support of state and federal officials. But nearly everywhere Dr. Chu turned, officials repeatedly rejected the idea, interviews and emails show, even as weeks crawled by and outbreaks emerged in countries outside of China, where the infection began.

By Feb. 25, Dr. Chu and her colleagues could not bear to wait any longer. They began performing coronavirus tests, without government approval.

What came back confirmed their worst fear. They quickly had a positive test from a local teenager with no recent travel history. The coronavirus had already established itself on American soil without anybody realizing it.

And to think Helen is only an assistant professor.

Data gathering and presentation prize: Avi Schiffmann

Here is a good write-up on Avi Schiffmann, excerpt:

A self-taught computer maven from Seattle, Avi Schiffmann uses web scraping technology to accurately report on developing pandemic, while fighting misinformation and panic.

Avi started doing this work in December, remarkable prescience, and he is only 17 years old. Here is a good interview with him:

I’d like to be the next Avi Schiffmann and make the next really big thing that will change everything.

Here is Avi’s website, ncov2019.live/data.

Prize for good policy thinking: The Imperial College researchers, led by Neil Ferguson, epidemiologist.

Neil and his team calculated numerically what the basic options and policy trade-offs were in the coronavirus space. Even those who disagree with parts of their model are using it as a basic framework for discussion. Here is their core paper.

The Financial Times referred to it as “The shocking coronavirus study that rocked the UK and US…Five charts highlight why Imperial College’s research radically changed government policy.”

The New York Times reported “White House Takes New Line After Dire Report on Death Toll.” Again, referring to the Imperial study.

Note that Neil is working on despite having coronavirus symptoms. His earlier actions were heroic too:

Ferguson has taken a lead, advising ministers and explaining his predictions in newspapers and on TV and radio, because he is that valuable thing, a good scientist who is also a good communicator.

Furthermore:

He is a workaholic, according to his colleague Christl Donnelly, a professor of statistical epidemiology based at Oxford University most of the time, as well as at Imperial. “He works harder than anyone I have ever met,” she said. “He is simultaneously attending very large numbers of meetings while running the group from an organisational point of view and doing programming himself. Any one of those things could take somebody their full time.

“One of his friends said he should slow down – this is a marathon not a sprint. He said he is going to do the marathon at sprint speed. It is not just work ethic – it is also energy. He seems to be able to keep going. He must sleep a bit, but I think not much.”

Prize for rapid speedy response: Curative, Inc. (legal name Snap Genomics, based in Silicon Valley)

Originally a sepsis diagnostics company, they very rapidly repositioned their staff and laboratories to scale up COVID-19 testing. They also acted rapidly, early, and pro-actively to round up the necessary materials for such testing, and they are currently churning out a high number of usable test kits each day, with that number rising rapidly. The company is also working on identifying which are the individuals most like to spread the disease and getting them tested first. here is some of their progress from yesterday.

Testing and data are so important in this area.

General remarks and thanks: I wish to thank both the founding donor and all of you who have subsequently made very generous donations to this venture. If you are a person of means and in a position to make a donation to enable this work to go further, with more prizes and better funded prizes, please do email me.

Super spreader immunity vs. herd immunity, from Paul Seabright

Dear Tyler,

I’ve read the comments section of your post on herd immunity pretty carefully and a point nobody has yet brought out is the importance of variance in R0. Suppose that an average R0 of 2.72 is made up of a) a low spreader subset of 90% of the population with R0 of 0.8 and b) 10% of super spreaders with an R0 of 20.

If what makes super spreaders different from the rest is just some invisible genetic factor, then using the average R0 of 2.72 in simulations may be a good approximation, and relaxing social distancing after the first wave may indeed lead to a large second wave.

But if what makes super spreaders different is a behavioral characteristic that also makes them much more likely to be infected than the rest of the population during the first wave, then the effect of the first wave may be much more permanent than the average R0 of 2.72 can capture.

Suppose the first wave infects 5% of low spreaders and 50% of high spreaders. Then after the first wave the uninfected population consists of a much smaller proportion of super spreaders than before and R0 for that population drops dramatically (to 1.86 in this example).

More generally if there is variance in systematic individual characteristics that affect R0 (and not just chance factors particular to the first wave), then stopping the epidemic requires only that enough of the high R0 individuals acquire immunity. That may happen naturally in the first wave, or it might be something that policy could influence. We may soon be able to test this by looking for a second wave in China as restrictions are relaxed.

An even more general point is that, unlike in many other familiar contexts, inequality in R0 is really good news. It reduces the size of the set of individuals whose behavior you need to influence. The more inequality the better!

The Coronavirus Killed the Progressive Left

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column. Yes trolling, but trolling with the truth. Here are scattered excerpts:

— The egalitarianism of the progressive left also will seem like a faint memory. Elites are most likely to support wealth redistribution when they feel comfortable themselves, and indeed well-off coastal elites in California and the Northeast are a backbone of the progressive movement. But when these people feel threatened in their lives or occupations, or when the futures of their children suddenly seem less secure, redistribution will not be such a compelling ideal…

— The case for mass transit also will seem weaker, because subways and buses will be associated with the fear of Covid-19 transmission. In a similar fashion, the forces of NIMBY will become stronger, relative to those of YIMBY, because people secure in their isolated suburban homes will feel less stressed than those in densely packed urban apartment buildings.

— There is likely to be much more government intervention in some parts of the health-care sector, but it will focus on scarce hospital beds and ventilators, and enforce nasty triage, rather than being a benevolent move toward universal coverage. If anything, it will drive home the message that supply constraints are binding and America can’t have everything — hardly the traditional progressive message.

— — The climate change movement is likely to be another victim. How much have you heard about Greta Thunberg lately? Concern over the climate will seem like another luxury from safer and more normal times. In addition, the course of anti-Covid-19 efforts may not prove propitious for the climate change movement. If the fight against Covid-19 suddenly improves (perhaps a vaccine working very quickly?), Americans may come to expect the same in the fight against climate change.

There is much more at the link, of course some of you will hate it. And of course Sanders and Warren did not exactly dominate voter sentiment, and that was largely pre-Covid.