Category: Music

Songs Sold for a Song

In our principles textbook, Modern Principles, Tyler and I discuss securitization and give the interesting example of music securitization with the picture at right (I’m pretty proud of the caption.)

In our principles textbook, Modern Principles, Tyler and I discuss securitization and give the interesting example of music securitization with the picture at right (I’m pretty proud of the caption.)

But what has happened to these big purchases of song portfolios? Ted Gioia runs the numbers and finds that the rock stars sold at the top and the financiers are taking a bath!

On Thursday, Hipgnosis announced a plan to sell almost a half billion dollars of its song portfolio. They need to do this to pay down debt. That’s an ominous sign, because the songs Hipgnosis bought were supposed to generate lots of cash. Why can’t they handle their debt load with that cash flow?

But there was even worse news. Hipgnosis admitted that they sold these songs at 17.5% below their estimated “fair market value.” This added to the already widespread suspicion that current claims of song value are inflated.

Hipgnosis’s share price actually dropped after the announcement.

Last year, I predicted the following:

“Don’t be surprised if the folks at [private equity group] Blackstone end up owning all those songs. But if it happens, they will probably acquire the music at a sharp discount to what those songs were worth just a few months ago.”

Can you guess the buyer in the deal announced on Thursday? Yes, it was a Blackstone-backed fund. And they definitely got that discount.

But there’s one part of this story that I love.…It confirms my sense that karma is at work in the universe, and everything tends towards justice and fairness—if you’re willing to wait long enough.

Here’s that element of karma. The old rock stars actually did defeat the system. They screwed the man, and did it big time.

By my measure, Bob Dylan sold out at the top, and gets to laugh at the financiers who overpaid him. The same is true of Paul Simon and Neil Young and all the rest.

When I launch my hedge fund, I’m going to invite them to join me as partners. They are shrewd operators, every one of them.

What should I ask Masaaki Suzuki?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is the opening of his Wikipedia page:

Masaaki Suzuki (鈴木 雅明, Suzuki Masaaki, born 29 April 1954) is a Japanese organist, harpsichordist and conductor, and the founder and music director of the Bach Collegium Japan. With this ensemble he is recording the complete choral works of Johann Sebastian Bach for the Swedish label BIS Records, for which he is also recording Bach’s concertos, orchestral suites, and solo works for harpsichord and organ. He is also an artist-in-residence at Yale University and the principal guest conductor of its Schola Cantorum, and has conducted orchestras and choruses around the world.

He is not just an incredible artist, he is one of the most remarkable achievers of our time. So what should I ask him?

Why is the minor key rising in popularity?

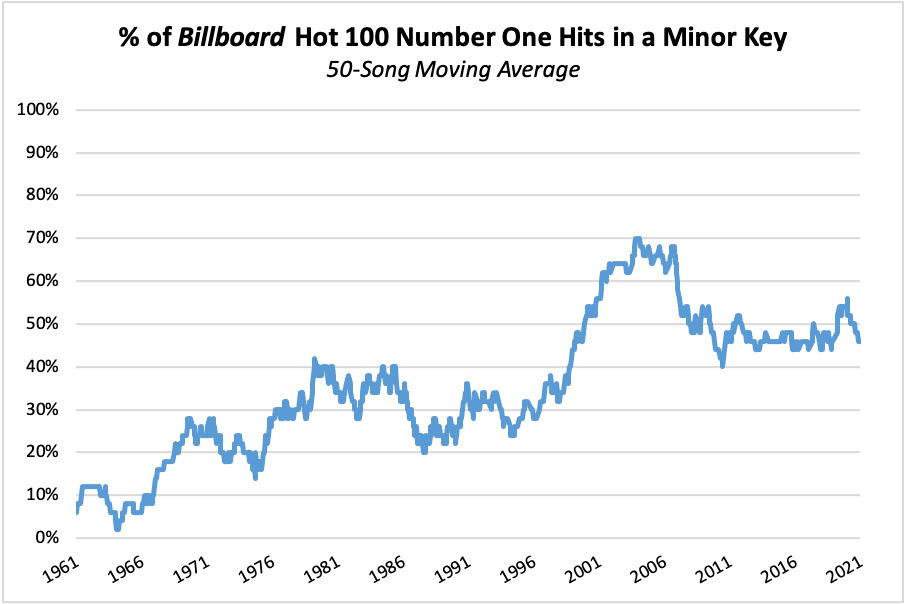

Another telltale sign of sad songs is the minor key. This rise in minor key songs has been dramatic. Around 85% of songs were in a major key back in the 1960s, but in more recent years this has fallen in half.

My favorite guru of music data analytics, Chris Dalla Riva, has sent me this chart showing the increasing share of Billboard #1 hits in a minor key. (By the way, I highly recommend Chris’s Substack Can’t Get Much Higher.)

Here is more from Ted Gioia.

Is Bach the greatest achiever of all time?

I’ve been reading and rereading biographies of Bach lately (for some podcast prep), and it strikes me he might count as the greatest achiever of all time. That is distinct from say regarding him as your favorite composer or artist of all time. I would include the following metrics as relevant for that designation:

1. Quality of work.

2. How much better he was than his contemporaries.

3. How much he stayed the very best in subsequent centuries.

4. Quantity of work.

5. Peaks.

6. Consistency of work and achievement.

7. How many other problems he had to solve to succeed with his achievement. For Bach, this might include a) finding musical manuscripts, b) finding organs good enough to play and compose on, c) dealing with various local and church authorities, d) migrating so successfully across jurisdictions, e) composing at an impossibly high level during the four years he was widowed (with kids), before remarrying.

8. Ending up so great that he could learn only from himself.

9. Never experiencing true defeat or setback (rules out Napoleon!).

I see Bach as ranking very, very high in all these categories. Who else might even be a contender for greatest achiever of all time? Shakespeare? Maybe, but Bach seems to beat him for relentlessness and quantity (at a very high quality level). Beethoven would be high on the list, but he doesn’t seem to quite match up to Bach in all of these categories. Homer seems relevant, but we are not even sure who or what he was. Archimedes? Plato or Aristotle? Who else?

Addendum: from Lucas, in the comments:

My Conversation with Vishy Anand

In Chennai I recorded with chess great Vishy Anand, here is the transcript, audio, and video, note the chess analysis works best on YouTube, for those of you who follow such things (you don’t have to for most of the dialogue). Here is the episode summary:

Tyler and Vishy sat down in Chennai to discuss his breakthrough 1991 tournament win in Reggio Emilia, his technique for defeating Kasparov in rapid play, how he approached playing the volatile but brilliant Vassily Ivanchuk at his peak, a detailed breakdown of his brilliant 2013 game against Levon Aronian, dealing with distraction during a match, how he got out of a multi-year slump, Monty Python vs. Fawlty Towers, the most underrated Queen song, how far to take chess opening preparation, which style of chess will dominate in the next ten years, how AlphaZero changes what we know about the game, the key to staying a top ten player at age 53, why he thinks he’s a worse loser than Kasparov, qualities he looks for in talented young Indian chess players, picks for the best places to eat in Chennai, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Do you hate losing as much as Kasparov does?

ANAND: To me, it seems he isn’t even close to me, but I admit I can’t see him from the inside, and he probably can’t see me from the inside. When I lose, I can’t imagine anyone in the world who loses as badly as I do inside.

COWEN: You think you’re the worst at losing?

ANAND: At least that I know of. A couple of years ago, whenever people would say, “But how are you such a good loser?” I’d say, “I’m not a good loser. I’m a good actor.” I know how to stay composed in public. I can even pretend for five minutes, but I can only do it for five minutes because I know that once the press conference is over, once I can finish talking to you, I can go back to my room and hit my head against the wall because that’s what I’m longing to do now.

In fact, it’s gotten even worse because as you get on, you think, “I should have known that. I should have known that. I should have known not to do that. What is the point of doing this a thousand times and not learning anything?” You get angry with yourself much more. I hate losing much more, even than before.

COWEN: There’s an interview with Magnus on YouTube, and they ask him to rate your sanity on a scale of 1 to 10 — I don’t know if you’ve seen this — and he gives you a 10. Is he wrong?

ANAND: No, he’s completely right. He’s completely right. Sanity is being able to show the world that you are sane even when you’re insane. Therefore I’m 11.

COWEN: [laughs] Overall, how happy a lot do you think top chess players are? Say, top 20 players?

ANAND: I think they’re very happy.

Most of all, I was struck by how good a psychologist Vishy is. Highly recommended, and you also can see whether or not I can keep up with Vishy in his chess analysis. Note I picked a game of his from ten years ago (against Aronian), and didn’t tell him in advance which game it would be.

When does the quality premium disappear?

I have been pondering the world of classical music once again, mostly because of two new releases. One is the late Beethoven string quartets by the Calidore Quartet, and the other is a six-CD Chopin box by Jean-Marc Luisada.

The most striking feature of these recordings is that they are as good as any in the case of the Beethoven, and top tier for the Chopin (yes I have heard Rubinstein, Horowitz playing Chopin live, Cortot, Dinu Lipatti, Bolet playing Chopin live, I know how to spell Krystian Zimerman, as for the Beethoven the Busch Quartet, Quartett Italiano, Alban Berg, Gewandhaus, Danish Quartet, and much more!)

A second striking feature of the status quo is that hardly anyone seems to have heard of these performers. Luisada has a Wikipedia article, but there don’t seem to be full-length profiles of him. The Calidore Quartet has a slightly longer Wikipedia article, but again there is no serious coverage of him on line. Hardly anyone has heard of them, and their releases will at best sell a few hundred copies.

I don’t think any people deny the quality of these offerings, though they may disagree on the exact nature of the superlatives to offer. The point is that few people care. Furthermore, few people care that few people care.

Still, I wonder…can there be other markets where there is so much quality available that the quality premium goes away? Note that in these equilibria, most customers are not listening to the very highest quality products, rather they may choose the products associated with greater celebrity (which typically are still very good though not the very best).

If all goes well in the world (ha), is this where ideas markets end up?

How about markets for Sichuan food? How many people really care about the very very best ma la?

Clearly the 18th century was very different. Adam Smith and David Hume were much, much better than virtually all of their contemporaries, and they reaped a high quality premium, at least in terms of fame, influence, and longevity.

What exactly makes the quality premium go away or dwindle?

Do we prefer a world with a lower quality premium, yet is such a world also bound to disappoint us morally?

My Conversation with the excellent Noam Dworman

I am very pleased to have recorded a CWT with Noam Dworman, mostly about comedy but also music and NYC as well. Noam owns and runs The Comedy Cellar, NYC’s leading comedy club, and he knows most of the major comedians. Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler sat down at Comedy Cellar with owner Noam Dworman to talk about the ever-changing stand-up comedy scene, including the perfect room temperature for stand-up, whether comedy can still shock us, the effect on YouTube and TikTok, the transformation of jokes into bits, the importance of tight seating, why he doesn’t charge higher prices for his shows, the differences between the LA and NYC scenes, whether good looks are an obstacle to success, the oldest comic act he still finds funny, how comedians have changed since he started running the Comedy Cellar in 2003, and what government regulations drive him crazy. They also talk about how 9/11 got Noam into trouble, his early career in music, the most underrated guitarist, why live music is dead in NYC, and what his plans are for expansion.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: If you do stand-up comedy for decades at a high level — not the Louis C.K. and Chris Rock level, but you’re successful and appear in your club all the time — how does that change a person? But not so famous that everyone on the street knows who they are.

DWORMAN: How does doing stand-up comedy change a person?

COWEN: For 25 years, yes.

DWORMAN: Well, first of all, it makes it harder for them to socialize. I hear this story all the time about comedians when they go to Thanksgiving dinner with their family, and all of a sudden, the entire place gets silent. Like, “Did he just say . . .” Because you get used to being in an atmosphere where you could say whatever you want.

I think probably, because I know this in my life — and again, getting used to essentially being your own boss, you get used to that. Then it just becomes very, very hard to ever consider going back into the structured life that most people expect is going to be their lives from the time they’re in school — 9:00 to 5:00, whatever it is. At some point, I think, if you do it for too long, you would probably kill yourself rather than go back.

I’ve had that thought myself. If I had to go back to . . . I never practiced law, but if I had to take a job as a lawyer — and I’m not just saying this to be dramatic — I think I might kill myself. I can’t even imagine, at my age, having to start going to work at nine o’clock, having a boss, having to answer for mistakes that I made, having the pressure of having to get it right, otherwise somebody’s life is impacted. I just got too used to being able to do what I want when I want to do it.

Comedians have to get gigs, but essentially, they can do what they want when they want to do it. They don’t have to get up in the morning, and I think, at some point, you just become so used to that, there’s no going back.

Recommended, interesting throughout.

Sinead O’Connor, RIP

Sinead O’Connor was a great singer–never more evident than in her collection of standards, Am I Not Your Girl? The entire album is wonderful. So sad to hear of her passing. Here on the painful decline of a marriage, Success Has Made a Failure of Our Home. Kills me every time I hear it.

From Faith and Courage, I love The Lamb’s Book of Life.

Out of history we have come

With great hatred and little room

It aims to break our hearts

Wreck us up and tear us all apart

But if we listen to the Rasta man

He can show us how it can be done

To live in peace and live as one

Get our names back in the book of life of the lamb

Here to cheer me up is Sinead in happier times, Daddy I’m fine, also from Faith and Courage.

Amazingly, her album of reggae songs Throw Down Your Arms, is very good. Who else could have pulled that off?

One more, from the Chieftain’s Long Black Veil–many great songs but none better than Sinead’s Foggy Dew, now the definitive version.

And back through the glen, I rode again

And my heart with grief was sore

For I parted then with valiant men

Whom I never shall see n’more

But to and fro in my dreams I go

And I kneel and pray for you

For slavery fled, O glorious dead

When you fell in the foggy dew

RIP Sinead. Thank you for the great music.

My excellent Conversation with David Bentley Hart

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

David Bentley Hart is an American writer, philosopher, religious scholar, critic, and theologian who has authored over 1,000 essays and 19 books, including a very well-known translation of the New Testament and several volumes of fiction.

In this conversation, Tyler and David discuss ways in which Orthodox Christianity is not so millenarian, how theological patience shapes the polities of Orthodox Christian nations, how Heidegger deepened his understanding of Christian Orthodoxy, who played left field for the Baltimore Orioles in 1970, the simplest way to explain how Orthodoxy diverges from Catholicism, the future of the American Orthodox Church, what he thinks of the Book of Mormon, whether theological arguments are ultimately based on reason or faith, what he makes of reincarnation and near-death experiences, gnosticism in movies and TV, why he dislikes Sarah Ruden’s translation of the New Testament, the most difficult word to translate, a tally of the 15+ languages he knows, what he’ll work on next, and more.

Hart is probably the best-read CWT guest of all time, with possible competition from Dana Gioia? Excerpt:

COWEN: If you could explain to me, as simply as possible, in which ways is Orthodox Christianity not so very millenarian?

HART: Well, it depends on what you mean by millenarian. I’d have to ask you to be a bit more —

COWEN: Say the Protestant 17th-century sense that the world is on the verge of a very radical transformation that will herald in some completely new age, and we all should be prepared for it.

HART: Well, in one sense, it’s been the case of Christianity from the first century that it’s always existed in a time between times. There’s always this sense of being in history but always expecting an imminent interruption of history.

But Orthodoxy has been around for a while. It’s part of an underrated culture, grounded originally in the Eastern Greco-Roman world, and has a huge apparatus of philosophy and theology and, I think, over the centuries has learned to be patient.

The Protestant millenarianism you speak of always seems to have been born out of historical crisis in a sense. The rise of the nation-state, the fragmentation of the Western Church — it’s always as much an effective history as a flight from history.

Whereas, I think it’s fair to say that Orthodoxy has created for itself a parallel world just outside the flow of history. It puts much more of an emphasis on the spiritual life, mysticism, that sort of thing. And as such, whereas it still uses the recognizable language of the imminent return of Christ, it’s not at the center of the spiritual life.

COWEN: How does that theological patience shape the polities of Orthodox Christian nations and regions? How does that matter?

HART: Well, it’s been both good and bad, to be honest. At its best, Orthodoxy has cultivated a spiritual life that nourished millions and that puts an emphasis upon moral obligation to others and the life of charity and the ascetical virtues of Christianity, the self-denial. At its worst, however, it’s often been an accommodation with historical forces that are antithetical to the gospel, too.

It’s often been the case that Orthodoxy has been so, let’s say, disenchanted with the millenarian expectation that it’s become a prop of the state, and you can see it today in Russia, in which you have a church institution. Now, this isn’t to speak of the faithful themselves, but the institutional authority of the state — of the institution, rather, of the church more or less being nothing but a propaganda wing of an authoritarian and terrorist government.

So, it’s had both its good and its bad consequences over the centuries. At its best, as I say, it encourages a true spiritual life that can teach one to be detached from ambitions and expectations and the violent projects of the ego. But at its worst, it can become a passive participant in precisely those sorts of projects and those sorts of evils.

Recommended, interesting throughout, and yes I do ask him about the Baltimore Orioles.

Messiaen’s Vingts Regards sur l`Enfant Jesus, by Krystoffer Hyldig

Emergent Ventures winners, 26th cohort

Winston Iskandar, 16, Manhattan Beach, CA, an app for children’s literacy and general career development. Winston also has had his piano debut at Carnegie Hall.

ComplyAI, Dheekshita Kumar and Neha Gaonkar, Chicago and NYC, to build an AI service to speed the process of permit application at local and state governments.

Avi Schiffman and InternetActivism, “leading the digital front of humanitarianism.” Avi is a repeat winner.

Jarett Cameron Dewbury, Ontario, and Cambridge MA, General career support, AI and biomedicine, including for the study of environmental enteric dysfunction. Here is his Twitter.

Ian Cheshire, Wallingford, Pennsylvania, high school sophomore, general career support, tech, start-ups, and also income-sharing agreements.

Beyzamur Arican Dinc, psychology Ph.D student at UCSB, regulation of emotional dyads in relationships and marriages, from Istanbul.

Ariana Pineda, Evanston, Illinois, Northwestern. To attend a biology conference in Prospera, Honduras.

Satvik Agnihotri, high school, NYC area, to visit the Bay Area for a summer, study logistics, and general career development.

Michael Loftus, Ann Arbor, for a neuro tech hacker house, connected to Myelin Group.

Keir Bradwell, Cambridge, UK, Political Thought and Intellectual History Masters student, to visit the U.S. to study Mancur Olson and Judith Shklar, and also to visit GMU.

Vaneeza Moosa, Ontario, incoming at University of Calgary, “Developing new therapies for malignant pleural mesothelioma using epigenetic regulators to enhance tumor growth and anti-tumor immunity with radiation therapy.”

Ashley Mehra, Yale Law School, background in classics, general career development and for eventual start-up plans.

An important project not yet ready to be announced, United Kingdom.

Jennifer Tsai, Waterloo, Ontario and Geneva (temporarily), molecular and computational neuroscience, to study in Gregoire Courtine’s lab.

Asher Parker Sartori, Belmont, Massachusetts, working with Nina Khera (previous EV winner), summer meet-up/conference for young bio people in Hanover, New Hampshire.

Nima Pourjafar, 17, starting this fall at Waterloo, Ontario. For general career development, interested in apps, programming, economics, solutions to social problems.

Karina, 17, sophomore in high school, neuroscience, optics, and light, Bellevue, Washington.

Sana Raisfirooz, Ontario, to study bioelectronics at Berkeley.

James Hill-Khurana (left off an earlier 2022 list by mistake), Waterloo, Ontario, “A new development environment for digital (chip) design, and accompanying machine learning models.”

Ukraine winners

Tetiana Shafran, Kyiv, piano, try this video or here are more. I was very impressed.

Volodymyr Lapin, London, Ukraine, general career development in venture capital for Ukraine.

What should I ask Ada Palmer?

I will be doing a Conversation with her. She is a unique thinker and presence, and thus hard to describe. Here is a brief excerpt from her home page:

I am an historian, an author of science fiction and fantasy, and a composer. I teach in the History Department at the University of Chicago.

Yes, she has tenure. Her four-volume Terra Ignota series is a landmark of science fiction, and she also has a deep knowledge of the Renaissance, Francis Bacon, and the French Enlightenment. She has been an advocate of free speech. Here is her “could be better” Wikipedia page. The imaginary world of her novels is peaceful, prosperous, obsessed with the Enlightenment (centuries from now), suppresses both free speech and gender designations, and perhaps headed for warfare once again?

Here is her excellent blog, which among other things considers issues of historical progress, and also her problems with chronic pain management and disability.

So what should I ask her?

*The Lost Album of the Beatles*

The author is Daniel Rachel, and the subtitle is What if The Beatles Hadn’t Split Up? This is perfectly fine as a music book (for Beatle fans, it won’t convince the unconverted), but I couldn’t stop thinking of the Lucas critique.

For the author, the Beatles “final last album” is a double album of the best cuts from Beatle early solo careers, and that is an impressive assemblage indeed. McCartney’s “Back Seat of My Car,” for instance, was written in 1968, or at least started in that year, so surely it would have ended up on the last album. Or would it have? It didn’t end up on Let It Be or Abbey Road, so who knows? As long as the end of The Beatles was in sight, perhaps each Beatle would have hoarded his best potential solo material. Or maybe the other Beatles would have vetoed some of those songs, just as Paul in 1968 had decided that George’s “Isn’t a Pity?” wasn’t suitable as a Beatles song. Or maybe John and Paul would have had to give more songs to George and Ringo, to keep the group together, but arguably to the detriment of the final album. Most of the songs on All Things Must Pass are very good, but best suited to their own little walled garden.

In contrast, this economist believes that an additional album would have fallen somewhere between Let It Be and The White Album, with an overall sound somewhat akin to “Free as a Bird,” or perhaps also Ringo’s “I’m the Greatest,” penned by John and cut with George as well. Good stuff, but I’m still glad they split. Get that Q up, especially given that market power was present!

And don’t assume that Beatle behavior remains invariant across different policy regimes. Lucas truly was a universal economist.

Wings at the Speed of Sound — a review

Was it Ian Leslie I promised this review to? Time is slipping away!

Speed of Sound (songs at the link) was much derided upon its release in 1976, and more recently one scathing reviewer gave it a “1” score out of 10. Yet I find this an entertaining and also compelling work. At least Eoghan Lyng had the sense to call it “definitely infectious and decidedly hummable.” But it’s better than that, and I would stress the following:

1. The album very definitely has its own “sound.” Super clean production, a limpid clarity in the mix, and sparing deployment of guitar. Not all of that works all the time, but there is a coherence to a production often described as a mish-mash. The sound of the whole is best reflected by “The Note You Never Wrote,” a McCartney song sung by Denny Laine, placed wisely in the number two slot. Nothing on either the disc or the original album sounds compressed, rather it all comes to life. It’s better than the sluggish, overproduced, horn-heavy Venus and Mars.

2. The unapologetic presentation has held up fine, rejecting its own era of albums that were overloaded with ideas, overproduced, and too self-consciously parading their messages. Speed of Sound is so deliberately unhip you can hardly believe it — who else in 1976 would pay tribute to “Phil and Don” of the Everly Brothers? And Paul was thanking MLK (“Martin Luther”) when others were still flirting with the Black Panthers. Surely he was right that “Silly Love Songs” would persist, so maybe people were hating on how on the mark he was.

2. At exactly the same time Wings was evolving into one of the very best live acts of the 1970s, far better than the Beatles ever were. (Yes, I know it is hard to admit that.) Their live act sizzled, and yes I did see it back then and I have listened to it many times since. Check out the YouTube channel of jimmymccullochfan, for instance “Beware My Love” or “Soily,” or how about “Call Me Back Again“? For Macca, Wings at this time was essentially a live band, and it proved to be his greatest live band achievement of all time (with some competition from his early 1990s shows), most of all pinned down by Jimmy McCulloch on guitar and Paul on bass.

You have to think of Speed of Sound as a complementary valentine to the live shows, a sweeter and more digestible version of what went into the road. Most of all it is about Paul and Linda, about the maturation of Wings as a group, about opennness to the world and to each other (a recurring Macca theme) and about domestic life, with recurring melancholy thrown in. Maybe those ideas are not your bag, but at least you can accept this as one piece of the broader McCartney tableau.

Now Macca knew you might not know about the live shows, but he didn’t care. He figured he was giving you two monster hits (“Let Em In,” “Silly Love Songs”) in the process, and that was good enough. And yes I agree he was too much the satisficer in this period.

3. The weak songs are “Wino Junko” and “Time to Hide” — 10% less democracy as Garett Jones says! “Time to Hide” is almost good, but it relies too heavily on horns and then drags on. “San Ferry Anne” also has a weak use of horns and the melody never quite takes off. “Cook of the House” goes into a category of its own. I’ll say only Wings [sic] needed to get this out of its system to move on to other approaches. I am pleased, however, that the lyrics are fulsome in their praise of domesticity, compare it to Lennon’s effort in an analogous but not similar vein. I don’t mind “dares to be appalling” as much as many others do. Frankly, I enjoy this song.

4. Excellent are “Let ’em In,” “The Note You Never Wrote,” “She’s My Baby,” “Beware My Love,” “Silly Love Songs,” and “Warm and Beautiful.” That is six very good songs on an album, with “Must Do Something About It” as “pretty good.” The prominence of the former set on Beatles XM satellite radio should not go unremarked, as presumably listeners are not switching the dial away. These songs are still popular nearly fifty years later.

5. “She’s My Baby” is the most underrated cut of that lot. It starts before you realize it and it just gets down to business. Thumping bass, innovative vocal, it keeps on going and then it segues into “Beware My Love.” Does not wear out its welcome.

6. There is no good reason to mock “Silly Love Songs,” which is a classic, ecstatic in its peaks, and which deploys disco influences in just the right way. The vocal and bass lines work perfectly, as does Linda’s vocal counterpoint. It stays vital at almost six minutes long. Once you step out of your ingrained bias, it is easy to see this is better than many of the classic McCartney Beatle songs. I would rather hear it than say Lennon’s soppy “Imagine,” which is ideologically ill-conceived to boot. Macca in this one is sly, mocking, and sardonic too, such as when he subtly refers to the problematic nature of mutual orgasm (“love doesn’t come in a minute…sometimes it doesn’t come at all…”).

7. “I must be wrong” in “Beware My Love” (plus the preceding guitar break) and “I love you” in “Silly Love Songs” are the two highlight moments of the album.

There are definitely disappointments in this work, but it is time we were able to view its contributions with some objectivity. Wings at the Speed of Sound is an excellent album, still worth the relistens. And I really am glad that the Beatles broke up — it meant more music from the group as a whole.