Category: Philosophy

What is opera?

The quality common to all the great operatic roles, e.g., Don Giovanni, Norma, Lucia, Tristan, Isolde, Brunnhilde, is that each of them is a passionate and willful state of being. In reali life they would all be bores, even Don Giovanni.

In recompense for this lack of psychological complexity, however, music can do what words cannot, present the immediate and simultaneous relation of these states to each other. The crowning glory of opera is the big ensemble.

That is from an excellent W.H. Auden essay “Notes on Music and Opera.”

Matt Yglesias on aphantasia

What I tend to approach from the outside are unpleasant experiences. Life is a mix of ups and downs, but I’m not really haunted by sad experiences or disturbing things that I’ve seen. I can tell you about the time I found a dead body in the alley and called the authorities to report it, and my recollection is it was pretty gross, but I certainly don’t have any pictures of that in my iPhone.

Sometimes I see something that causes me to update my views of the world. But when I saw the body, I was already aware, factually, that drug overdose deaths were becoming common in D.C., so I felt that I hadn’t really learned anything new. At the time I was victimized by crime, the amount of violent crime in this city had been on a steady downward trend for a very long time, so it didn’t cause me to change my views at all. Several years later, that downward trend started to reverse and, after a few years of gradual growth, there were some sharp jumps, and then I got worried and started calling for policy changes.

And I think this is a strength of the aphantasic worldview. Something bad happened to me that was statistically anomalous, so I didn’t change my views. When the broader situation changed, I did change my views, even though actually nothing bad happened to me personally. And that’s because the right way to assess crime trends is to try to get a statistically valid view of the situation, not overindex on the happenstance of your life.

Here is the full essay. Here is Hollis Robbins on related issues.

My Conversation with the excellent Donald S. Lopez Jr.

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Donald discuss the Buddha’s 32 bodily marks, whether he died of dysentery, what sets the limits of the Buddha’s omniscience, the theological puzzle of sacred power in an atheistic religion, Buddhism’s elaborate system of hells and hungry ghosts, how 19th-century European atheists invented the “peaceful” Buddhism we know today, whether the axial age theory holds up, what happened to the Buddha’s son Rahula, Buddhism’s global decline, the evidently effective succession process for Dalai Lamas, how a guy from New Jersey created the Tibetan Book of the Dead, what makes Zen Buddhism theologically unique, why Thailand is the wealthiest Buddhist country, where to go on a three-week Buddhist pilgrimage, how Donald became a scholar of Buddhism after abandoning his plans to study Shakespeare, his dream of translating Buddhist stories into new dramatic forms, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Fire is a central theme in Buddhism, right?

LOPEZ: Well, there are hot hells, and there are also cold hells. Fire comes up, really, in the idea of nirvana. Where we see the fire, I think most importantly, philosophically, is the idea of where did the Buddha go when he died? He was not reborn again. They say it’s really just like a flame going out, that is, the flame ends. Where did the fire go? Nowhere, that is, the wood that was producing the flame is all burned up, and you just end. Nirvana is not a place. It’s a state of extinction or what the Buddhists call cessation.

COWEN: What role does blood sacrifice play in Buddhism?

LOPEZ: Well, it’s not supposed to perform any role. There’s no blood sacrifice in Buddhism.

COWEN: No blood sacrifice. How about wrathful deities?

LOPEZ: Wrathful deities — there’re a lot, yes.

COWEN: Then we’re back to supernatural. Again, this gets to my central confusion. It’s atheistic, but there’s some other set of principles in the universe that generate wrathful deities, right?

LOPEZ: Wrathful deities are beings who were humans in one lifetime, animals in another, and born as wrathful deities in another lifetime. Everyone is in the cycle of rebirth. We’ve all been wrathful deities in the past. We’ll be wrathful deities in the future unless we get out soon. It’s this universe of strange beings, all taking turns, shape-shifting from one lifetime to the next, and it goes on forever until we find the way out.

COWEN: Are they like ghosts at all — the wrathful deities?

LOPEZ: There’s a whole separate category of ghosts. The ghosts are often called — if we look at the Chinese translation — hungry ghosts. The ghosts are beings who suffer from hunger and thirst. They are depicted as having distended bellies. They have these horrible sufferings that when they drink water, it turns into molten lead. They’ll eat solid food — it turns into an arrow or a spear. Constantly seeking food, constantly being frustrated, and they appear a lot in Buddhist text. One of the jobs of Buddhist monks and nuns is to feed the hungry ghosts.

COWEN: Is it a fundamental misconception to think of Buddhism as a peaceful religion?

And:

COWEN: …If one goes to Borobudur in Java — spectacular, one of the most amazing places to see in the world.

LOPEZ: Absolutely.

COWEN: We read that it was abandoned. It wasn’t even converted into a tourist site or a place where you would sell things. Why would you just toss away so much capital structure?

LOPEZ: I think it just got overgrown by the jungle. I think that people were not going there. There were no Buddhist pilgrims coming. The populace converted to Islam mostly, and it just fell into decline, just to be revived in the 19th, 20th century.

COWEN: Turn it into a candy store or something! It just seems capital maintenance occurs across other margins. The best-looking building you have — one of the best-looking in the world — is forgotten. Don’t you find that paradoxical?

Definitely recommended, interesting throughout and I learned a great deal doing the prep. One of my favorite episodes of this year. And I am happy to recommend all of Donald’s books on Buddhism.

Andrej and Dwarkesh as philosophy

If you follow AI at all, you probably do not need another recommendation of the Andrej Karpathy and Dwarkesh Patel podcast, linked to here:

I hardly ever listen to podcasts, but at almost two and a half hours I found this one worthwhile and that was at 1x (I don’t listen to podcasts at higher speed, not wanting to disrupt the drama of the personalities). What struck me is how philosophical so many aspects of the discussion were. Will this end up being the best “piece of philosophy” done this year? Probably. Neither participant of course is a trained philosopher, but neither were Plato or Kierkagaard. They are both very focused on real issues however, and new issues at that. And dialogue is hardly a disqualifying medium when it comes to philosphy.

Some guy on Twitter felt I was slighting this book in my tweet on the matter. I’ll let history judge this one, as we’ll see which issues people are still talking about fifty years from now (note I said nothing against that book in my tweet, nor against contemporary philosophy, I just said this podcast was philosophical and very good). I’ve made the point before (pre-LLM) that current academic philosophers are losing rather dramatically in the fight for intellectual influence, and perhaps more of a serious engagement with these issues would help. I’ve seen plenty of philosophical work on AI, but none of it yet seems to be interesting. For that you have to go to the practitioners and the Bay Area obsessives.

The cosmopolitan conservative

From the excellent Janan Ganesh (FT):

Often, it is fear of causing offence that stops liberal-minded people engaging with vast tracts of the world. And so cultural sensitivity turns into its own kind of parochialism. If Forsyth was a workmanlike writer, he had a grander twin in VS Naipaul, who wrote on a global canvas despite or because of personal attitudes that some call reactionary. (Others have used a different r-word about him.) A modern liberal would not be as cutting about Africa and south-east Asia as Naipaul, it is true. But then don’t assume that a modern liberal would, in either sense of the phrase, “go there” at all.

I even wonder if a small amount of jingoism helps. You have to see the world from somewhere. The branding of this column, Citizen of Nowhere, is tongue-in-cheek: a reference to an old speech by one of our lesser prime ministers here in Britain. The truth is, without a starting point to which one is attached, it is hard to even register cultural differences, let alone comment on them. The result is that weird flattening jargon in which well-meaning people address the world. Rory Stewart remembers some first-class diplomatic baloney during his time in Afghanistan. “Every Afghan is committed to a gender-sensitive, multi-ethnic centralised state . . . ” and so on.

Recommended.

David Brooks on the New Right

Excellent David Brooks column on how the right has adopted the theories and tools of the left:

As so many have noted, MAGA is identity politics for white people. It turns out that identity politics is more effective when your group is in the majority.

…Last year, a writer named James Lindsay cribbed language from “The Communist Manifesto,” changed its valences so that they were right wing and submitted it to a conservative publication called The American Reformer. The editors, unaware of the provenance, were happy to print it. When the hoax was revealed, they were still happy! The right is now eager to embrace the ideas that led to tyranny, the gulag and Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Interestingly, the right didn’t take the leftist ideas that were intended to build something; they took just the ideas intended to destroy.

Read the whole thing.

*The Master of Contradictions*

The author is Morten Jensen, and the subtitle is Thomans Mann and the Making of The Magic Mountain. An excellent introduction to Mann’s tome, and it many fine discussions. Here is one excerpt:

It becomes possible, then, to read The Magic Mountain as a novel partly about the limits and failures of the more positivistic strain of nineteenth-century liberalism — a triumphalist worldview that failed to recognize or halt Europe’s drift toward nationalism, reaction, and the industrial carnage of the First World War. Settembrini, the noveläs representative of this worldview, shares its myriad flaws, beliving, for instance, that self-perfection is the ultimate goal of humankind. And like so many nineteenth-century liberal utopians, he celebrates technology as “the most dependable means by which to bring nations closer together, furthering their knowledge of one another, paving the way for people-to-people exchanges, destroying prejudices, and leading at last to the universal brotherhood of nations.

…More than just a vessel for a philosophical point of view, however, Settembrini is, or becomes, one of The Magic Mountain’s most endearing characters. One cannot help but smile a little — half with affection, half with pity — whenever he enters the stage. It’s one of the novel’s great distinctions that its central characters are never merely reducible to the philosophical worldview they represent; Settembrini, even when Mann is at his most sarcastic, is always first and foremost Settembrini, as if Mann were gradually convinced by his fictional creation as a dynamic individual rather than a static representation.

Recommended.

Informative jury disagreement

The article introduces a counterintuitive argument, contending that jury disagreement on the defendant’s guilt-a nonunanimous conviction-may well provide a more informative signal, compared to consensus. Because stronger consensus implies higher likelihood of herding, it is shown that beyond some threshold, further accumulation of votes to convict would carry negligible epistemic contribution, barely enhancing the posterior probability of guilt. On the other hand, while dissenting votes provide a direct signal of innocence, they indicate that herding has not been involved in the decision-making process, hence increase the epistemic contribution of any vote generated by said processincluding votes to convict-and may thus offer an indirect signal of guilt, potentially increasing the posterior. This unravels the informational value of dissent and the possible disadvantageousness of consensus.

That is from a new paper by Roy Baharad, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Helen Andrews on the feminization of culture

Thiel and Wolfe on the Antichrist in literature

Jonathan Swift tried to exorcise Baconian Antichrist-worship from England. Gulliver’s Travels agreed with New Atlantis on one point: The ancient hunger for knowledge of God had competition from the modern thirst for knowledge of science. In this quarrel between ancients and moderns, Swift sided with the former.

Gulliver’s Travels takes us on four voyages to fictional countries bearing scandalous similarities to eighteenth-century England. In his depictions of the Lilliputians, Brobdingnagians, Laputans, and Houyhnhnms, Swift lampoons the Whig party, the Tory party, English law, the city of London, Cartesian dualism, doctors, dancers, and many other people, movements, and institutions besides. Swift’s misanthropy borders on nihilism. But as is the case with all satirists, we learn as much from whom Swift spares as from whom he scorns—and Gulliver’s Travels never criticizes Christianity. Though in 2025 we think of Gulliver’s Travels as a comedy, for Swift’s friend Alexander Pope it was the work of an “Avenging Angel of wrath.” The Anglican clergyman Swift was a comedian in one breath and a fire-and-brimstone preacher in the next.

Gulliver claims he is a good Christian. We doubt him, as we doubt Bacon’s chaplain. Gulliver’s first name, Lemuel, translates from Hebrew as “devoted to God.” But “Gulliver” sounds like “gullible.” Swift quotes Lucretius on the title page of the 1735 edition: “vulgus abhorret ab his.” In its original context, Lucretius’s quote describes the horrors of a godless cosmos, horrors to which Swift will expose us. The words “splendide mendax” appear below Gulliver’s frontispiece portrait—“nobly untruthful.” In the novel’s final chapter, Gulliver reflects on an earlier promise to “strictly adhere to Truth” and quotes Sinon from Virgil’s Aeneid. Sinon was the Greek who convinced the Trojans to open their gates to the Trojan horse: one of literature’s great liars.

Here is the full article, interesting and varied throughout.

My excellent Conversation with John Amaechi

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. As I said on Twitter, John has the best “podcast voice” of any CWT guest to date. Here is the episode summary:

John Amaechi is a former NBA forward/center who became a chartered scientist, professor of leadership at Exeter Business School, and New York Times bestselling author. His newest book, It’s Not Magic: The Ordinary Skills of Exceptional Leaders, argues that leadership isn’t bestowed or innate, it’s earned through deliberate skill development.

Tyler and John discuss whether business culture is defined by the worst behavior tolerated, what rituals leadership requires, the quality of leadership in universities and consulting, why Doc Rivers started some practices at midnight, his childhood identification with the Hunchback of Notre Dame and retreat into science fiction, whether Yoda was actually a terrible leader, why he turned down $17 million from the Lakers, how mental blocks destroyed his shooting and how he overcame them, what he learned from Jerry Sloan’s cruelty versus Karl Malone’s commitment, what percentage of NBA players truly love the game, the experience of being gay in the NBA and why so few male athletes come out, when London peaked, why he loved Scottsdale but had to leave, the physical toll of professional play, the career prospects for 2nd tier players, what distinguishes him from other psychologists, why personality testing is “absolute bollocks,” what he plans to do next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Of NBA players as a whole, what percentage do you think truly love the game?

AMAECHI: It’s a hard question to answer. Well, let me give a number first, otherwise, it’s just frustrating. 40%. And a further 30% like the game, and 20% of them are really good at the game and they have other things they want to do with the opportunities that playing well in the NBA grants them.

But make no mistake, even that 30% that likes the game and the 40% that love the game, they also know that they like what the game can give them and the opportunities that can grow for them, their families and generation, they can make a generational change in their family’s life and opportunities. It’s not just about love. Love doesn’t make you good at something. And this is a mistake that people make all the time. Loving something doesn’t make you better, it just makes the hard stuff easier.

COWEN: Are there any of the true greats who did not love playing?

AMAECHI: Yeah. So I know all former players are called legends, whether you are crap like me or brilliant like Hakeem Olajuwon, right? And so I’m part of this group of legends and I’m an NBA Ambassador as well. So I go around all the time with real proper legends. And a number of them I know, and so I’m not going to throw them under the bus, but it’s the way we talk candidly in the van going between events. It’s like, “Yeah, this is a job now and it was a job then, and it was a job that wrecked our knees, destroyed our backs, made it so it’s hard for us to pick up our children.”

And so it’s a job. And we were commodities for teams who often, at least back in those days, treated you like commodities. So yeah, there’s a lot of superstars, really, really excellent players. But that’s the problem, don’t conflate not loving the game. And also, don’t be fooled. In Britain there’s this habit of athletes kissing the badge. In football, they’ve got the badge on their shirt and they go, “Mwah, yeah.” If that fools you into thinking that this person loves the game, if them jumping into the stands and hugging you fools you into thinking that they love the game, more fool you.

COWEN: Michael Cage, he loved the game. Right?

But do note that most of the Conversation is not about the NBA.

My excellent Conversation with Steven Pinker

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Steven probe these dimensions of common knowledge—Schelling points, differential knowledge, benign hypocrisies like a whisky bottle in a paper bag—before testing whether rational people can actually agree (spoiler: they can’t converge on Hitchcock rankings despite Aumann’s theorem), whether liberal enlightenment will reignite and why, what stirring liberal thinkers exist under the age 55, why only a quarter of Harvard students deserve A’s, how large language models implicitly use linguistic insights while ignoring linguistic theory, his favorite track on Rubber Soul, what he’ll do next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Surely there’s a difference between coordination and common knowledge. I think of common knowledge as an extremely recursive model that typically has an infinite number of loops. Most of the coordination that goes on in the real world is not like that. If I approach a traffic circle in Northern Virginia, I look at the other person, we trade glances. There’s a slight amount of recursion, but I doubt if it’s ever three loops. Maybe it’s one or two.

We also have to slow down our speeds precisely because there are not an infinite number of loops. We coordinate. What percentage of the coordination in the real world is like the traffic circle example or other examples, and what percentage of it is due to actual common knowledge?

PINKER: Common knowledge, in the technical sense, does involve this infinite number of arbitrarily embedded beliefs about beliefs about beliefs. Thank you for introducing the title with the three dots, dot, dot, dot, because that’s what signals that common knowledge is not just when everyone knows that everyone knows, but when everyone knows that everyone knows that and so on. The answer to your puzzle — and I devote a chapter in the book to what common knowledge — could actually consist of, and I’m a psychologist, I’m not an economist, a mathematician, a game theorist, so foremost in my mind is what’s going on in someone’s head when they have common knowledge.

You’re right. We couldn’t think through an infinite number of “I know that he knows” thoughts, and our mind starts to spin when we do three or four. Instead, common knowledge can be generated by something that is self-evident, that is conspicuous, that’s salient, that you can witness at the same time that you witness other people witnessing it and witnessing you witnessing it. That can grant common knowledge in a stroke. Now, it’s implicit common knowledge.

One way of putting it is you have reason to believe that he knows that I know that he knows that I know that he knows, et cetera, even if you don’t literally believe it in the sense that that thought is consciously running through your mind. I think there’s a lot of interplay in human life between this recursive mentalizing, that is, thinking about other people thinking about other people, and the intuitive sense that something is out there, and therefore people do know that other people know it, even if you don’t have to consciously work that through.

You gave the example of norms and laws, like who yields at an intersection. The eye contact, though, is crucial because I suggest that eye contact is an instant common knowledge generator. You’re looking at the part of the person looking at the part of you, looking at the part of them. You’ve got instant granting of common knowledge by the mere fact of making eye contact, which is why it’s so potent in human interaction and often in other species as well, where eye contact can be a potent signal.

There are even species that can coordinate without literally having common knowledge. I give the example of the lowly coral, which presumably not only has no beliefs, but doesn’t even have a brain with which to have beliefs. Coral have a coordination problem. They’re stuck to the ocean floor. Their sperm have to meet another coral’s eggs and vice versa. They can’t spew eggs and sperm into the water 24/7. It would just be too metabolically expensive. What they do is they coordinate on the full moon.

On the full moon or, depending on the species, a fixed number of days after the full moon, that’s the day where they all release their gametes into the water, which can then find each other. Of course, they don’t have common knowledge in knowing that the other will know. It’s implicit in the logic of their solution to a coordination problem, namely, the public signal of the full moon, which, over evolutionary time, it’s guaranteed that each of them can sense it at the same time.

Indeed, in the case of humans, we might do things that are like coral. That is, there’s some signal that just leads us to coordinate without thinking it through. The thing about humans is that because we do have or can have recursive mentalizing, it’s not just one signal, one response, full moon, shoot your wad. There’s no limit to the number of things that we can coordinate creatively in evolutionarily novel ways by setting up new conventions that allow us to coordinate.

COWEN: I’m not doubting that we coordinate. My worry is that common knowledge models have too many knife-edge properties. Whether or not there are timing frictions, whether or not there are differential interpretations of what’s going on, whether or not there’s an infinite number of messages or just an arbitrarily large number of messages, all those can matter a lot in the model. Yet actual coordination isn’t that fragile. Isn’t the common knowledge model a bad way to figure out how coordination comes about?

And this part might please Scott Sumner:

COWEN: I don’t like most ballet, but I admit I ought to. I just don’t have the time to learn enough to appreciate it. Take Alfred Hitchcock. I would say North by Northwest, while a fine film, is really considerably below Rear Window and Vertigo. Will you agree with me on that?

PINKER: I don’t agree with you on that.

COWEN: Or you think I’m not your epistemic peer on Hitchcock films?

PINKER: Your preferences are presumably different from beliefs.

COWEN: No. Quality relative to constructed standards of the canon…

COWEN: You’re going to budge now, and you’re going to agree that I’m right. We’re not doing too well on this Aumann thing, are we?

PINKER: We aren’t.

COWEN: Because I’m going to insist North by Northwest, again, while a very good movie is clearly below the other two.

PINKER: You’re going to insist, yes.

COWEN: I’m going to insist, and I thought that you might not agree with this, but I’m still convinced that if we had enough time, I could convince you. Hearing that from me, you should accede to the judgment.

I was very pleased to have read Steven’s new book

What should I ask Alison Gopnik?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. Here is Wikipedia:

Alison Gopnik (born June 16, 1955) is an American professor of psychology and affiliate professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley. She is known for her work in the areas of cognitive and language development, specializing in the effect of language on thought, the development of a theory of mind, and causal learning. Her writing on psychology and cognitive science has appeared in Science, Scientific American, The Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, New Scientist, Slate and others. Her body of work also includes four books and over 100 journal articles…

Gopnik has carried out extensive work in applying Bayesian networks to human learning and has published and presented numerous papers on the topic…Gopnik was one of the first psychologists to note that the mathematical models also resemble how children learn.

Gopnik is known for advocating the “theory theory” which postulates that the same mechanisms used by scientists to develop scientific theories are used by children to develop causal models of their environment.

Here is her home page. So what should I ask her?

The new Derek Parfit volume

He also talked about more personal matters such as his severe problems with insomnia during the recent book-writing process, saying that he was sometimes awake for thirty-six hours at a time and felt that if he had had a gun to hand he might have shot himself — not because he wanted to die, but because he was desperate to lose consciousness. He had eventually been recommended to try a sleep regime and calming drugs that had solved the problem, and when I commented that I also had problems with sleep, he immediately suggested I should try his methods too. I discovered later that whenever he came across some technique he regarded as providing a major life improvement, he would proselytize it far and wide.

That is from Janet Radcliffe Richard, the widow of Derek Parfit. Her fascinating spousal memoir is from the new and fascinating edited collection Derek Parfit: His Life and Thought, edited by Jeff McMahan. Worth the triple digit price. Derek would exercise on a stationery bike only, because that was the only form of exercise compatible with reading. And he was a big fan of Uchida playing Mozart, as all people should be.

And there is this segment, near the close of the essay:

…in the eyes of some people who were aware of it, my philosophical standing was if anything diminished, because in Derek’s circle I was merely his partner, and barely known otherwise. He did not open up new opportunities for me; on the contrary, I rather dropped out of public view when we lived togehter. He did not widen my social circle, because he did not have one; in practice (not deliberately), he severely contracted it. He was of little use for anything recreational, because we did together only what he wanted to do, and soon after I met him most possibilities of that kind were perpetually over the horizon. He did not in any way advance my career: he was neither my teacher nor my referee, and I had started to establish my terrain — very different from his — before I knew him. I learned an enormous amount from him, of course; but I did not often find it helpful to discuss my work with him. Even my eventual return to Oxford had nothing to do with him.

Recommended. Larry Temkin tells us that Parfit could not calculate a fifteen percent tip, and there is an essay by Derek’s brother as well. I have never seen a volume where the contributors evince so much fierce loyalty and attachment to their subject.

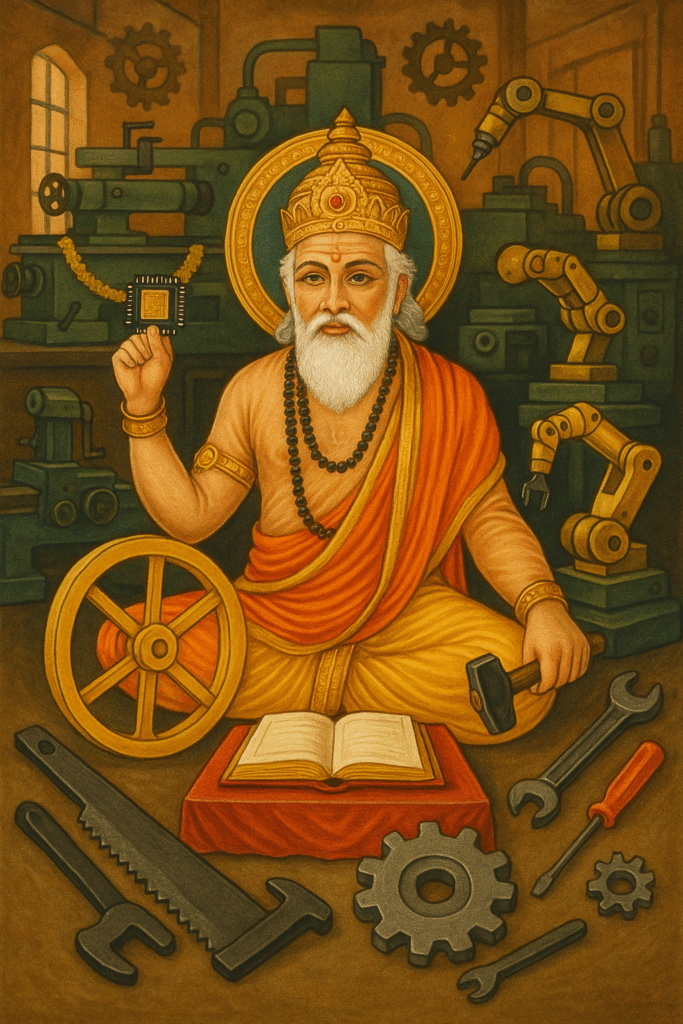

Celebrate Vishvakarma: A Holiday for Machines, Robots, and AI

Most holidays celebrate people, gods or military victories. Today is India’s Vishvakarma Puja, a celebration of machines. In India on this day, workers clean and honor their equipment and engineers pay tribute to Vishvakarma, the god of architecture, engineering and manufacturing.

Most holidays celebrate people, gods or military victories. Today is India’s Vishvakarma Puja, a celebration of machines. In India on this day, workers clean and honor their equipment and engineers pay tribute to Vishvakarma, the god of architecture, engineering and manufacturing.

Call it a celebration of Solow and a reminder that capital, not just labor, drives growth.

Capital today isn’t just looms and tractors—it’s robots, software, and AI. These are the new force multipliers, the machines that extend not only our muscles but our minds. To celebrate Vishvakarma is to celebrate tools, tool makers and the capital that makes us productive.

We have Labor Day for workers and Earth Day for nature. Viskvakarma Day is for the machines. So today don’t thank Mother Earth, thank the machines, reflect on their power and productivity and be grateful for all that they make possible. Capital is the true source of abundance.

Vishvakarma Day should be our national holiday for abundance and progress.

Hat tip: Nimai Mehta.