Category: Philosophy

Principles, from Nabeel

14. You don’t do anyone any favors by lurking, put yourself out there!

15. If you don’t “get” a classic book or movie, 90% of the time it’s your fault. (It might just not be the right time for you to appreciate that thing.)

16. If you find yourself dreading Mondays, quit…

23. Doing things is energizing, wasting time is depressing. You don’t need that much ‘rest’.

24. Being able to travel is one of the key ways the modern world is better than the old world. Learn to travel well.

Here is the full list.

My podcast with Reason

With Liz Wolfe and Zach Weissmueller:

The link here contains the YouTube video, text description, and links to audio versions at reason.com: https://reason.com/podcast/2025/01/10/tyler-cowen-why-do-we-refuse-to-learn-from-history/

Youtube page for embedding is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-Kpyg2mFU8

Lots of about libertarianism and state capacity libertarianism, and The Great Forgetting, food at the end…interesting throughout!

Podcast with Misha Saul

Misha lives in Sydney and works in finance and is very smart. Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Some bullet points:

- “[Agency has] one of the most skewed distributions I can think of”

- “You look like you have kids. I thought you would have kids.”

- “You’re going to drive Melbourne into the ground and it will be your fault.”

- “It’s striking to me when I receive Emergent Ventures applications, which is all in English, of course. I hardly ever get any from Australia.”

- Tyler on who he is in German: “Dreamier, more romantic, maybe more relaxed, less obsessed with getting work done.”

There is a good bit of new material in here.

Richard A. Easterlin, RIP

He was one of the fathers of “happiness economics,” here is a NYT obituary. Via John Chamberlin.

My 92nd St. Y debate with Robert Kuttner on income inequality

Here goes:

Ex po st, the Manhattan audience swung thirty (!) points in my favor, compared to the pre-debate poll. This was a fun event for me.

My Shakespeare and literature podcast with Henry Oliver

Here is the audio and transcript, here is the episode summary:

Tyler and I spoke about view quakes from fiction, Proust, Bleak House, the uses of fiction for economists, the problems with historical fiction, about about drama in interviews, which classics are less read, why Jane Austen is so interesting today, Patrick Collison, Lord of the Rings… but mostly we talked about Shakespeare. We talked about Shakespeare as a thinker, how Romeo doesn’t love Juliet, Girard, the development of individualism, the importance and interest of the seventeenth century, Trump and Shakespeare’s fools, why Julius Cesar is over rated, the most under rated Shakespeare play, prejudice in The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare as an economic thinker. We covered a lot of ground and it was interesting for me throughout.

Excerpt:

Henry No, I agree with you. The thing I get the most pushback about with Shakespeare is when I say that he was a great thinker.

Tyler He’s maybe the best thinker.

And:

Henry Sure. So you’re saying Juliet doesn’t love Romeo?

Tyler Neither loves the other.

Henry Okay. Because my reading is that Romeo has a very strong death drive or dark side or whatever.

Tyler That’s the strong motive in the play is the death drive, yeah.

Henry and I may at some point do a podcast on a single Shakespeare play.

Questions that are rarely asked

“Which do you think is the best symphony which you never have heard?”

It used to be the first two symphonies of Carl Nielsen, but yesterday I heard them. They are good, probably not great, but in any case I never had heard them before. I have heard more Haydn symphonies than you might think (all of them), so for me the answer is not one of those.

Perhaps now it is something by Lutoslawski? I only know two of them, and I like them. What else does this margin hold? And how long will I need to explore it?

This question gets at two issues. First, how do you assess matters you do not really know? What kinds of evidence do you bring to bear on answering this question?

Second, why do you stop at one margin rather than another? Why don’t you know whatever you think is the best symphony you have never heard? Was your last attempt in that direction such a miserable failure? Are symphonies really so bad? I think not. No matter who you are, there are still some good ones.

So what is stopping you?

Is there an intermediate position on immigration?

It is a common view, especially on the political right, that we should be quite open to highly skilled immigrants, and much less open to less skilled immigrants. Increasingly I am wondering whether this is a stable ideological equilibrium.

To an economist, it is easy to see the difference between skilled and less skilled migrants. Their wages are different, resulting tax revenues are different, and social outcomes are different, among other factors. Economists can take this position and hold it in their minds consistently and rather easily (to be clear, I have greater sympathies for letting in more less skilled immigrants than this argument might suggest, but for the time being that is not the point).

The fact that economists’ intuitions can sustain that distinction does not mean that public discourse can sustain that distinction. For instance, perhaps “how much sympathy do you have for foreigners?” is the main carrier of the immigration sympathies of the public. If they have more sympathies for foreigners, they will be relatively pro-immigrant for both the skilled and unskilled groups. If they have fewer sympathies for foreigners, they will be less sympathetic to immigration of all kinds. Do not forget the logic of negative contagion.

You also can run a version of this argument with “legal vs. illegal immigration” being the distinction at hand.

Increasingly, I have the fear that “general sympathies toward foreigners” is doing much of the load of the work here. This is one reason, but not the only one, why I am uncomfortable with a lot of the rhetoric against less skilled immigrants. It may also be the path toward a tougher immigration policy more generally.

I hope I am wrong about this. Right now the stakes are very high.

In the meantime, speak and write about other people nicely! Even if you think they are damaging your country in some significant respects. You want your principles here to remain quite circumscribed, and not to turn into anti-foreigner sentiment more generally.

Full-length documentary on the life and legacy of Rene Girard

Very well done.

Dwarkesh Patel interviews me at the Progress Studies conference

Recommended, interesting and humorous throughout.

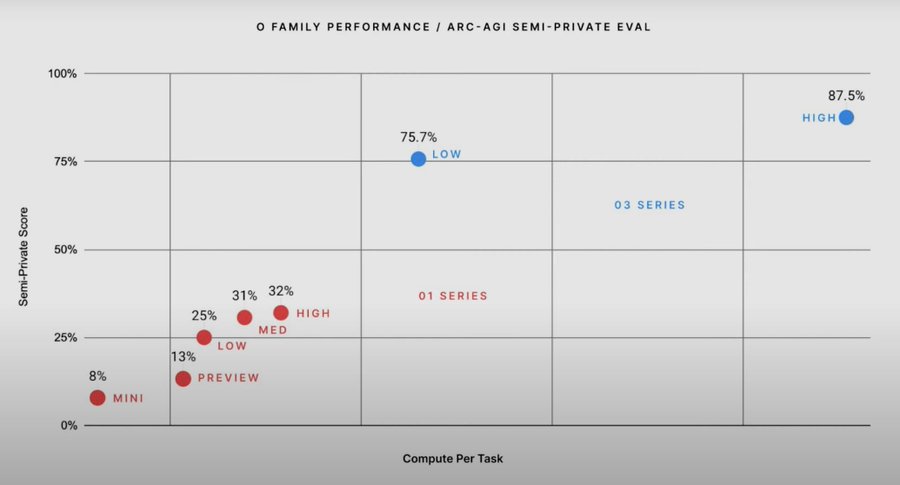

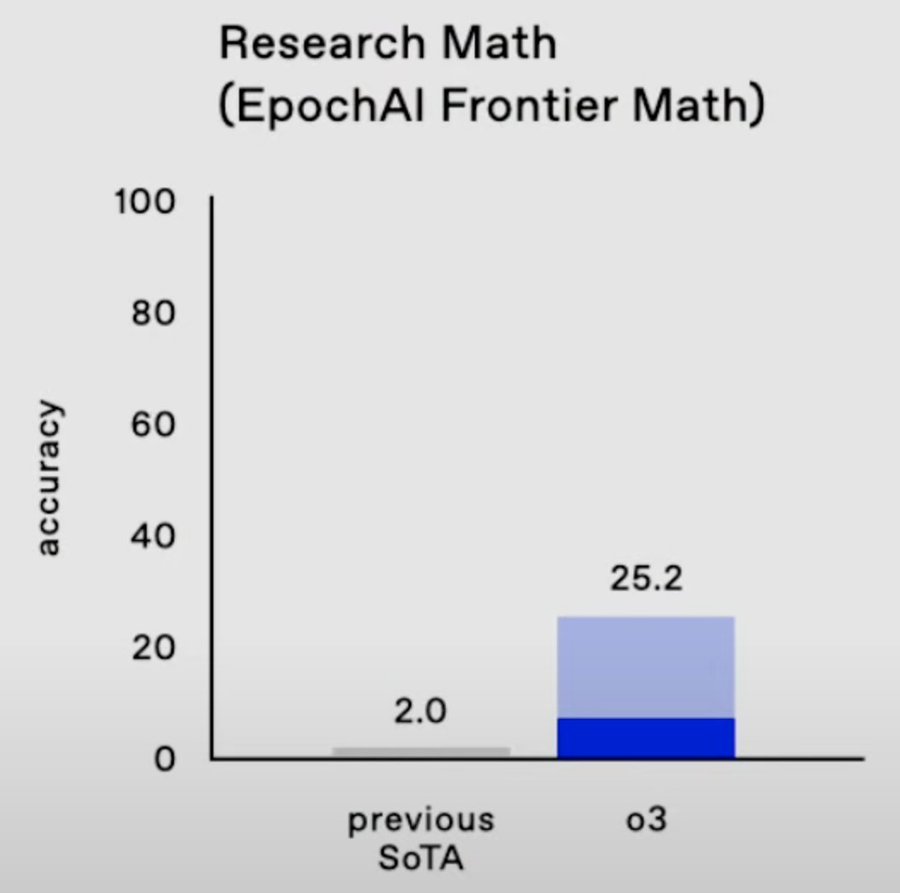

The new o3 model from OpenAI

Some more results. And this:

Yupsie-dupsie, delivery of this:

Happy holidays people, hope you are enjoying the presents!

Why you should be talking with gpt about philosophy

I’ve talked with Gpt (as I like to call it) about Putnam and Quine on conceptual schemes. I’ve talked with it about Ζeno’s paradoxes. I’ve talked with it about behaviourism, causality, skepticism, supervenience, knowledge, humour, catastrophic moral horror, the container theory of time, and the relation between different conceptions of modes and tropes. I tried to get it to persuade me to become an aesthetic expressivist. I got it to pretend to be P.F. Strawson answering my objections to Freedom and Resentment. I had a long chat with it about the distinction between the good and the right.

…And my conclusion is that it’s now really good at philosophy…Gpt could easily get a PhD on any philosophical topic. More than that, I’ve had many philosophical discussions with professional philosophers that were much less philosophical than my recent chats with Gpt.

Here is the full Rebecca Lowe Substack on the topic. There are also instructions for how to do this well, namely talk with Gpt about philosophical issues, including ethics:

In many ways, the best conversation I’ve had with Gpt, so far, involved Gpt arguing against itself and its conception of me, as both Nozick1 (the Robert Nozick who sadly died in 2002) and Nozick2 (the imaginary Robert Nozick who is still alive today, and who according to Gpt has developed into a hardcore democrat), on the topic of catastrophic moral horror.

And as many like to say, this is the worst it ever will be…

The epistemics of drone incursions

I do not pretend to know what is going on, nor do I think it is aliens. I do read:

The sprawling Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio is the latest military installation to report mysterious drones flying over its airspace, The War Zone has learned.

“I can confirm small aerial systems were spotted over Wright Patterson between Friday night and Saturday morning,” base spokesman Bob Purtiman told The War Zone on Sunday in response to our questions about the sightings. “Today leaders have determined that they did not impact base residents, facilities, or assets. The Air Force is taking all appropriate measures to safeguard our installations and residents.”

The drones “ranged in sizes and configurations,” Purtiman said. “Our units are working with local authorities to ensure the safety of base personnel, facilities, and assets.”

The airspace over the base was closed for a while. My point here is to beware self-styled “debunkers,” who often acquire excess ownership in a schtick. Most of all I mean figures such as Mick West. It is easy enough to find stupid claims about drones (especially in New Jersey?) and counter them. The better way to proceed is to confront the strongest claims head on. The head of DHS is mystified, and a classified security briefing was held for Congress. Those are puzzles we should try to figure out. There is at least a reasonable probability that something interesting is going on here. Beware debunkers, very often they are not your epistemic friends.

Addendum: Here is an update from a man who receives high-level intelligence briefings.

My Conversation with the excellent Paula Byrne

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Paula discuss Virginia Woolf’s surprising impressions of Hardy, why Wessex has lost a sense of its past, what Jude the Obscure reveals about Hardy’s ideas about marriage, why so many Hardy tragedies come in doubles, the best least-read Hardy novels, why Mary Robinson was the most interesting woman of her day, how Georgian theater shaped Jane Austen’s writing, British fastidiousness, Evelyn Waugh’s hidden warmth, Paula’s strange experience with poison pen letters, how American and British couples are different, the mental health crisis among teenagers, the most underrated Beatles songs, the weirdest thing about living in Arizona, and more.

This was one of the most fun — and funny — CWTs of all time. But those parts are best experienced in context, so I’ll give you an excerpt of something else:

COWEN: Your book on Evelyn Waugh, the phrase pops up, and I quote, “naturally fastidious.” Why can it be said that so many British people are naturally fastidious?

BYRNE: Your questions are so crazy. I love it. Did I say that? [laughs]

COWEN: I think Evelyn Waugh said it, not you. It’s in the book.

BYRNE: Give me the context of that.

COWEN: Oh, I’d have to go back and look. It’s just in my memory.

BYRNE: That’s really funny. It’s a great phrase.

COWEN: We can evaluate the claim on its own terms, right?

BYRNE: Yes, we can.

COWEN: I’m not sure they are anymore. It seems maybe they once were, but the stiff-upper-lip tradition seems weaker with time.

BYRNE: The stiff upper lip. Yes, I think Evelyn Waugh would be appalled with the way England has gone. Naturally fastidious, yes, it’s different to reticent, isn’t it? Fastidious — hard to please, it means, doesn’t it? Naturally hard to please. I think that’s quite true, certainly of Evelyn Waugh because he was naturally fastidious. That literally sums him up in a phrase.

COWEN: If I go to Britain as an American, I very much have the feeling that people derive status from having negative opinions more than positive. That’s quite different from this country. Would you agree with that?

Definitely recommended, one of my favorite episodes in some while. And of course we got around to discussing Paul McCartney and Liverpool…

*A Boy’s Own Story*

By Edmund White, I enjoyed this paragraph from the preface:

In A Boy’s Own Story I touched on all the themes of my youth: the exaggerated consolations of the imagination; the sexy but crushing teenage culture of the 1950s; the importance of Buddhism, books and psychoanalysis to my development; my first contacts with bohemianism, the sole milieu where homosexuality was tolerated; and finally my cult of physical beauty. In recent years politically correct gay critics have taken me to task for my *looksism.” I never respond, but if I were to I’d say “Put the blame on Plato, who originated the seductive if unwholesome idea that physical beauty is a promise of Beauty, indistinguishable from Truth and Goodness.” All artists are responsive to beauty in any form it appears.

How did “looksism” get turned into “lookism“?