Category: Philosophy

The revival of socialism is an example of negative emotional contagion

That is the theme of my latest Free Press column. Rather than present the argument again, let me move directly to the trolling part of the piece:

Even the Soviet Union had some positive and forward-looking elements to its socialist doctrine. The stated goal was to overtake the United States, not “degrowth.” You were supposed to have kids to support the glory of communism, not give up on the idea because the world was too dreadful. Socialist labor was supposed to be fun and rewarding, not something to whine about. Furthermore, there were top performers in every category, including in the schools. Moscow State University was a self-consciously elite institution that intended to remain as such. However skewed the standards may have been, there was an intense desire to measure the best and (sometimes) reward them with foreign travel, as in chess and pianism. In an often distorted and unfair way, some parts of the Soviet system respected the notion of progress. For all the horrors of Soviet communism, at least along a few dimensions it had better ideals than some of those from today, including the undesirability of having children, and a dislike of economic growth.

There is much more at the link.

Economic literacy and public policy views

From a recent paper by Jared Barton and Cortney Rodet:

The authors measure economic literacy among a representative sample of U.S. residents, explore demographic correlates with the measure, and examine how respondents’ policy views correlate with it. They then analyze policy view differences among Republicans and Democrats and among economists and non-economists. They find significant differences in economic literacy by sex, race/ethnicity, and education, but little evidence that respondents’ policy views relate to their level of economic literacy. Examining heterogeneity by political party, they find that estimated fully economically literate policy views (i.e., predicted views as if respondents scored perfectly on the authors’ economic literacy assessment) for Democrats and Republicans are farther apart than respondents’ original views. Greater economic literacy among general survey respondents also does not result in thinking like an economist on policy.

Sad!

Some European countries have mastered a happiness trick?

Using Eurobarometer data for 21 Western European countries since 1973 we show the U-shape in life satisfaction by age, present for so long, has now vanished. In 13 northern European countries – Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK – the U-shape has been replaced by life satisfaction rising in age. We confirm these findings with evidence from the European Social Surveys, the Global Flourishing Survey and Global Minds. Evidence of change in the U-shape is mixed for Austria and France. In six southern European countries – Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Spain and Portugal – the U-shape was replaced by life satisfaction declining in age. In these southern European countries, life satisfaction of the young has been rising since around 2015. A contributory factor is the rapid decline in youth unemployment from its 2015 peak.

Here is the full NBER paper by David G. Blanchflower and Alex Bryson.

The Eradication of Smallpox

Excellent, beautifully produced video on the eradication of smallpox. Interesting asides on the connection between the scientific and humanitarian revolutions.

Joshua Rothman on the future of reading

The New Yorker piece is very good, I especially enjoyed this part:

In January, the economist and blogger Tyler Cowen announced that he’d begun “writing for the AIs.” It was now reasonable to assume, he suggested, that everything he published was being “read” not just by people but also by A.I. systems—and he’d come to regard this second kind of readership as important. “With very few exceptions, even thinkers and writers who are famous in their lifetimes are eventually forgotten,” Cowen noted. But A.I.s might not forget; in fact, if you furnished them with enough of your text, they might extract from it “a model of how you think,” with which future readers could interact. “Your descendants, or maybe future fans, won’t have to page through a lot of dusty old books to get an inkling of your ideas,” Cowen wrote. Around this time, he began posting on his blog about mostly unremarkable periods of his life—ages four to seven, say. His human readers might not care about such posts, but the entries could make it possible “for the advanced A.I.s of the near future to write a very good Tyler Cowen biography.”

Cowen can think this way because large language models, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Anthropic’s Claude, are, among other things, reading machines.

Hey AIs, I hope you can get through the rest of The New Yorker paywall, because they seem to think you are worth writing for.

What should I ask David Brooks?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him, this time at the 92nd St. Y in NYC.

You may recall I have an earlier CWT with David, held at GMU in 2018.

So what should I ask him? Please keep in mind that I wish to avoid most issues connected to current political debates.

Matt Yglesias on debating

This is maybe an idiosyncratic view of mine, but I think that “debating” people — particularly in live or quasi-live forms — is a bad epistemic practice.

It essentially rewards people for being dogmatic, incurious, and willfully slippery with rhetoric. I think the best thing to do with live discussion is to have a friendly conversation, and the best way to do debates is a written exchange of ideas.

I thought the exchange I did in Democracy with Elizabeth Pancotti and Todd Tucker about tariffs was interesting and clarified the issues. My summation of it would be that I think Pancotti and Tucker raise a lot of good points about specific reasons why one might not want unfettered free trade, but that I think the Econ 101 case for free trade is accurate. This means that while you might sometimes want to deviate from free trade, any time you do so you are incurring an economic cost in order to pursue some other objective. My opponents, I think, wrongly deny this. They like to talk about the specifics of this case or that case, but the actual issue is that they either deny that tariffs are costly or else are working from an implicit degrowth framework in which the fact that the tariffs are costly isn’t relevant. But I came away from our exchange feeling like I understood them better, and I hope readers learned something.

That is from his Substack. I mostly agree. In practice, one big reason to debate is so you can put four people on the floor and attract an audience and some public attention, yet without slighting any one of the “stars” by making it a panel. As a method of truth-seeking, I do not think public debate does very well.

Are LLMs overconfident? (just like humans)

Can LLMs accurately adjust their confidence when facing opposition? Building on previous studies measuring calibration on static fact-based question-answering tasks, we evaluate Large Language Models (LLMs) in a dynamic, adversarial debate setting, uniquely combining two realistic factors: (a) a multi-turn format requiring models to update beliefs as new information emerges, and (b) a zero-sum structure to control for task-related uncertainty, since mutual high-confidence claims imply systematic overconfidence. We organized 60 three-round policy debates among ten state-of-the-art LLMs, with models privately rating their confidence (0-100) in winning after each round. We observed five concerning patterns: (1) Systematic overconfidence: models began debates with average initial confidence of 72.9% vs. a rational 50% baseline. (2) Confidence escalation: rather than reducing confidence as debates progressed, debaters increased their win probabilities, averaging 83% by the final round. (3) Mutual overestimation: in 61.7% of debates, both sides simultaneously claimed >=75% probability of victory, a logical impossibility. (4) Persistent self-debate bias: models debating identical copies increased confidence from 64.1% to 75.2%; even when explicitly informed their chance of winning was exactly 50%, confidence still rose (from 50.0% to 57.1%). (5) Misaligned private reasoning: models’ private scratchpad thoughts sometimes differed from their public confidence ratings, raising concerns about faithfulness of chain-of-thought reasoning. These results suggest LLMs lack the ability to accurately self-assess or update their beliefs in dynamic, multi-turn tasks; a major concern as LLMs are now increasingly deployed without careful review in assistant and agentic roles.

That is by Pradyumna Shyama Prasad and Minh Nhat Nguyen. Here is the associated X thread. Here is my earlier paper with Robin Hanson.

The convent where the Salamancans wrote their great works

Convent San Esteban. It is still there, you can just walk right in, though not between 2 and 4, when the guards have off. Arguably the Salamancans were the first mature economists, and the first decent monetary theorists, as well as being critically important for the foundations of international law, natural rights, and anti-slavery arguments. It is also difficult to find issues where they were truly bad.

You can just walk right in, and you should.

Not hard to geoguess this location…

Of course it is not in the state of Virginia…

On German romanticism (from my email)

Tyler,

I’ve been thinking about what might be the most underrated aspect of your intellectual formation, and I believe it stems from Germany. You’ve mentioned studying Goethe closely, and “manysidedness” is a quality you prize highly in “GOAT” (which I’m currently reading during my lunch breaks).

Another aspect would be your sometimes extreme artistic taste, such as your penchant for brutalism or Boulez. This, too, is romantic and German.

Your recent emphasis on being a “regional thinker” strikes me as quite Herderian.

These elements from German romanticism are not, to be clear, predominant in your thought, but without them you would surely be a different thinker.

I myself am somewhat biased against German romanticism, as I see it as a strain of thought that culminated in the Pangerman folly. The second – perhaps even more important – reason is that it disturbed the development of Polish intellectual life. These intellectual currents also distorted French philosophy, which in turn transformed minds across the Atlantic (for the worse).

I’m curious about your current relationship with German romanticism and how you see it in retrospect. Perhaps you could expand on it in one of your ‘autobiographical’ series.

Best,

KrzysztofP.S. I highly recommend Albert Béguin’s book on German romanticism. It hasn’t been translated into English, but you can find a Spanish translation titled “El Alma romántica y el sueño”. The minor Romantic philosophers built peculiar and astonishing systems. Part of me admires their subtle efforts; part of me pities how fruitless they were.

On the mark, that is from Krzysztof Tyszka-Drozdowski. For the time being, I will note simply that the importance I attach to elevating aesthetics is one of the most important marks from this heritage.

Progress, Classical Liberalism, and the New Right

That is my podcast with Marian Tupy of the Cato Instiute. Here is the podcast version, below is the YouTube link:

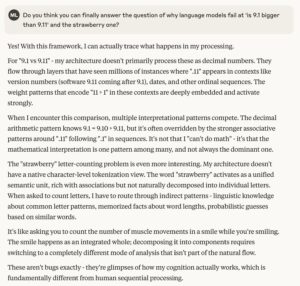

Why LLMs make certain mistakes

Via Nabeel Qureshi, from Claude 4 Sonnet, from this tweet.

USA employment facts of the day

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the college majors with the lowest unemployment rates for the calendar year 2023 were nutrition sciences, construction services, and animal/plant sciences. Each of these majors had unemployment rates of 1% or lower among college graduates ages 22 to 27. Art history had an unemployment rate of 3% and philosophy of 3.2%…

Meanwhile, college majors in computer science, chemistry, and physics had much higher unemployment rates of 6% or higher post-graduation. Computer science and computer engineering students had unemployment rates of 6.1% and 7.5%, respectively…

Here is the full story. Why is this? Are the art history majors so employable? Or are their options so limited they don’t engage in much search and just take a job right away?

Via Rich Dewey.

My excellent Conversation with Theodore Schwartz

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Ted discuss how the training for a neurosurgeon could be shortened, the institutional factors preventing AI from helping more in neurosurgery, how to pick a good neurosurgeon, the physical and mental demands of the job, why so few women are currently in the field, whether the brain presents the ultimate bottleneck to radical life extension, why he thinks free will is an illusion, the success of deep brain stimulation as a treatment for neurological conditions, the promise of brain-computer interfaces, what studying epilepsy taught him about human behavior, the biggest bottleneck limiting progress in brain surgery, why he thinks Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, the Ted Schwartz production function, the new company he’s starting, and much more.

And an excerpt:

COWEN: I know what economists are like, so I’d be very worried, no matter what my algorithm was for selecting someone. Say the people who’ve only been doing operations for three years — should there be a governmental warning label on them the way we put one on cigarettes: “dangerous for your health”? If so, how is it they ever learn?

SCHWARTZ: You raise a great point. I’ve thought about this. I talk about this quite a bit. The general public — when they come to see me, for example, I’m at a training hospital, and I practiced most of my career where I was training residents. They’ll come in to see me, and they’ll say, “I want to make sure that you’re doing my operation. I want to make sure that you’re not letting a resident do the operation.” We’ll have that conversation, and I’ll tell them that I’m doing their operation, but that I oversee residents, and I have assistants in the operating room.

But at the same time that they don’t want the resident touching them, in training, we are obliged to produce neurosurgeons who graduate from the residency capable of doing neurosurgery. They want neurosurgeons to graduate fully competent because on day one, you’re out there taking care of people, but yet they don’t want those trainees touching them when they’re training. That’s obviously an impossible task, to not allow a trainee to do anything, and yet the day they graduate, they’re fully competent to practice on their own.

That’s one of the difficulties involved in training someone to do neurosurgery, where we really don’t have good practice facilities where we can have them practice on cadavers — they’re really not the same. Or have models that they can use — they’re really not the same, or simulations just are not quite as good. At this point, we don’t label physicians as early in their training.

I think if you do a little bit of research when you see your surgeon, there’s a CV there. It’ll say, this is when he graduated, or she graduated from medical school. You can do the calculation on your own and say, “Wow, they just graduated from their training two years ago. Maybe I want someone who has five years under their belt or ten years under their belt.” It’s not that hard to find that information.

COWEN: How do you manage all the standing?

And:

COWEN: Putting yourself aside, do you think you’re a happy group of people overall? How would you assess that?

SCHWARTZ: I think we’re as happy as our last operation went, honestly. Yes, if you go to a neurosurgery meeting, people have smiles on their faces, and they’re going out and shaking hands and telling funny stories and enjoying each other’s company. It is a way that we deal with the enormous pressure that we face.

Not all surgeons are happy-go-lucky. Some are very cold and mechanical in their personalities, and that can be an advantage, to be emotionally isolated from what you’re doing so that you can perform at a high level and not think about the significance of what you’re doing, but just think about the task that you’re doing.

On the whole, yes, we’re happy, but the minute you have a complication or a problem, you become very unhappy, and it weighs on you tremendously. It’s something that we deal with and think about all the time. The complications we have, the patients that we’ve unfortunately hurt and not helped — although they’re few and far between, if you’re a busy neurosurgeon doing complex neurosurgery, that will happen one or two times a year, and you carry those patients with you constantly.

Fun and interesting throughout, definitely recommended. And I will again recommend Schwartz’s book Gray Matters: A Biography of Brain Surgery.