Category: Political Science

The pay of Presidents (from my email)

Adjusting for inflation, President Biden is one of the lowest-paid Presidents in American history. See the first and last figures in this analysis from 2012.

This source’s figures are all in 2012 dollars, and there’s been 39% cumulative inflation since then, while the President’s nominal salary has stayed fixed at $400,000/year (nominal). So Bill Clinton’s average real salary over his presidency – the lowest real historical pay as of the time of this source’s analysis – would be worth $403,100 today, just barely edging out Biden’s current salary of $400,000. (But Clinton’s average real salary was probably lower than Biden’s average salary over the course of Biden’s presidency. There have been a few years when the President’s real annual salary was below its current level, including during most of Clinton’s presidency.)

The last time the President’s real salary dropped down below its current level, Congress voted to double it.

That is from TP.

What to think about ranked choice voting?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one key segment:

Game theory can help explain how ranked choice voting changes the behavior of candidates, as well as the elites who support them. Consider a ranked choice election that has five or six candidates. To win the election, you can’t just appeal to your base. You also can’t alienate your opponent’s base. You want supporters of other candidates to regard you as “not too bad,” because if they hate you, they could rank you very low and get you tossed out of the running quickly.

Candidates are thus encouraged to moderate their positions and their behavior — that is, not to call each other too many names. If the favorite candidate of one voter calls the favorite of another “weird,” for example — to choose an example not quite at random — the latter voter might respond by voting down the name-caller to the very bottom.

The result? Negative campaigning diminishes, and politics moderates. The effect can be especially pronounced in party primaries, which sometimes are dominated by the most extreme voters.

The candidates also compete in different ways. In particular, they try to outdo each other when it comes to constituency service, which is a way of being popular without offending anybody.

The broader evidence on ranked choice voting shows that, when used, it has made US politics more moderate. Alaska’s ranked choice voting helped moderate Republican Lisa Murkowski beat her more ideological opponents in 2022. In Idaho, some conservatives regard ranked choice voting with suspicion, fearing it is a plot to neutralize their influence.

In Ireland, politics is fairly non-ideological on most matters of policy, and elections are not typically seen as major, course-altering events. After more than a century with this system, the Irish seem happy to keep it.

The lesson here is that it is not possible to evaluate ranked choice voting in the abstract. It usually makes politics less extreme and less ideological, but those are descriptive terms, not normative ones. I would prefer California’s politics to be less ideological, for example, but that is because it embodies an ideology distinct from mine. And sometimes the more extreme and ideological positions are entirely correct, as for instance John Stuart Mill’s advocacy of women’s suffrage and birth control in the 19th century.

In general, ranked choice voting is best for places where voters feel things are already on the right track and ought to stay there. It is a voting system for the self-satisfied. Which parts of contemporary America might that describe? No voting method yet devised can settle that question.

High and low decoupling, and other matters (from my email)

This is all from an anonymous reader, not by me, but I will not indent:

“Hi Tyler,

I enjoyed your post – I’m kind of tired of this – and wanted to respond to it as I think what you wrote gets at two important trends happening in politics today.

1 – High and Low Decoupling

First of all the examples of idiotic tribal behaviour you cited remind me of an idea I was first introduced to by Tom Chivers about the difference between high decouplers – individuals comfortable separating and isolating ideas from actions, and low decouplers – individuals who see ideas as inextricable from their wider contexts. – https://unherd.com/2020/02/eugenics-is-possible-is-not-the-same-as-eugenics-is-good/

I would argue that up until today low decoupling (along with the everpresent sin of motivated reasoning) has been the cultural norm in politics for over a century, if not longer, and so much of the bollocks we see in political rhetoric and in corporate news coverage across the western world can be explained by everyone having to conform to the norm if they want to succeed.

hat I would argue we are seeing now thanks to Twitter (and especially its inspired Community Notes feature) is the first proper challenge to the low decoupling cultural norm and the vacuum that is developing thanks to more and more people seeing (and criticising) politicians conforming to it. Indeed whilst the internet may not forget anything, up until Elon’s takeover of twitter the internet has been something of a toothless old dog.

How will this shift away from low decoupling change political discourse? I suspect it will make debate more elitist and less accessible for ordinary people because arguments will have to become more sophisticated and require a certain level of engagement to understand. This will probably make political discussions seem duller to many people due to a more analytical and rigorous style as opposed to the quick trite phrases of the present moment. because political actors will know that they can be “owned” or discredited as “fake news” if they are shown to be using spin or overly simplistic arguments. Counter intuitively (for those not paying attention) I also then think the decline of low decoupling will see the death of “fact checkers” because of the growing cynicism towards this movement and the growing appreciation of the fact that there are inherent biases underlying those checking the facts and that they often present their responses in emotive and low decoupling ways.

It’s important to say I don’t think this change will necessarily change everyone’s behaviour but then it doesn’t need to. If it just changes the behaviour of the 10-20% of the population who take a moderate to high interest in politics (and are more important for changes within politics) then this will change the discussion even if the remaining 80% are still by and large low decouplers on political matters. But this change will itself play into the wider changes we are seeing in politics and which is the other point I want to highlight.

2 – The political realignment

Now going back to your post, what is arguably more interesting is the subtext of what you said, specifically your (low decoupling) defence of the new right. It could be argued that a Straussian reading of what you are saying is that despite where you thought you would be in the political new realignment you keep finding yourself in a different position and you find this fact unsettling. I think it shouldn’t be. It’s just that the present framing of the realignment is wrong and based on outdated understandings of the forces involved.

Now in the established narrative the new realigned politics should pit socially conservative economic nationalists against cosmopolitan socially liberal centrists (and leftists). And for libertarians/classical liberals the argument by many has been that the best position for the libertarian/classical liberal right is towards the cosmopolitan liberal end of the spectrum due to alleged shared norms for open societies. However, I actually disagree with this interpretation as whilst it’s a good theory it does not fit the reality of what has happened or indeed is happening in western politics.

The cosmopolitan liberal tribe could be about a commitment to open societies and broad liberal values but the reality has been and I would argue continue to be (because of the need to include radical leftists in this divide) a commitment to egalitarianism and the social democratic (left liberal) norms of political conduct which are poorly designed for our very online, wealthy multiracial Western nations.

These norms have led to the toleration of state corruption and inefficiency “how dare you criticise the teachers”, “how dare you criticise the NHS”, “how are you criticise the EU/Federal government” and the promotion of cancellation against those who go against the established narrative on issues such as the speed/scope/direction of Net Zero, stand up for women’s rights against the trans ideology or who critique the current model of immigration/integration.

The cosmopolitan liberals are on a hiding to nothing with all of these issues. And why? Because they as a political wing represent the status quo, and what we are seeing now is the beginning of the end for the dominant post 1945 social democratic settlement. 2020-21 I would argue, with the twin pillars of massive state control through the excuse of COVID and the cultural dominance of the BLM/Woke movement, was Western social democracy at its apex and the longer that model to hold the more it will corrode and wither into either a Robespierre-esque focus on equity, or else a degeneration into deep green anti growth nihilism, either of which will kill it as a force anyway. This is why Emmanuel Macron now seems out of his depth, why Trudeau keeps failing, and why the European Union continues to stagnate – they are the status quo establishment and they’ve run out of ideas.

So what then do I think will take its place. Well inevitably one wing of politics seeks to preserve the status quo and one wing seeks to overturn it and looking at the ideas floating around the populist/rightist/nationalist camp we can already see trends emerging. Now I will caveat that it will take a while for these to develop as intellectually there is no fertile “home” for this wing (being excluded from academia and more generally all sympathetic intellectual figures being shunned/condemned/cancelled but substack seems to be developing into a way “rightist” intellectuals can work and be paid to be intellectuals. And those intellectuals will not be drinking from a barren pool and when we look at the expected intellectual influencers it gets hard for classical liberals/libertarians to pretend they have no sympathy with this movement.

Now in a previous comment you’ve stated you think that religious intellectual figures will be at the core of intellectual developments going forward but what I see is that the core figures will actually be 5 irreligious figures namely; Roger Scruton, Elinor Ostrom, Ayn Rand, Thomas Sowell and Lee Kuan Yew. Together these five offer a philosophical basis, an economic analysis and a political roadmap from which western rightist parties can seek direction. I struggle to think of 5 other intellectuals who could have more relevant ideas for the current moment. If I could term the ideology brewed from this pool of thought I would not call it populism or even national conservatism but State Capacity Localism (wink), or as a slogan, Politics for improving the oikos.

And looking at the current trends and discussions already happening within politics you can clearly see the influence of the 5 in the way the discussions on the right are beginning to articulate possible policies;

-

Improving state capacity through slewing the deadwood of the bureaucratic state with a burn it down/drain the swamp mentality.

-

Nationalisation offset by deregulation – probably a better compromise than what we have today.

-

Local/community decision making on contentious topics with a focus on finding solutions over the current model of finding problems (forced by national government with the threat of national decision if a local solution is not found)

-

The binning of multiculturalism as an idea and assimilation as the core of all arguments on immigration and racial/cultural integration. Combine this with increasing discussions on what countries have achieved high trust multiracial societies (spoiler – Singapore) I expect we will see a reflowering of support for secularism, the absolute necessity of learning the national language for access to employment and state services, and a zero tolerance for ethnic or religious based politics.

-

Tough law and order policies focused on objective outcomes over cultural contexts. President Bukele (and Gavin Newsom when Xi came to visit) prove it can work.

-

The return of aesthetics as a mode of political analysis – beautiful houses and pleasant neighbourhoods and with that an attempt to improve everywhere in a country, most especially rust belts/flyover country.

-

The introduction of land value taxes – which as an idea is literally the opposite of a transnational globalist politics in how it encourages rootedness by design.

-

A focus on high standards, individual responsibility and the veneration and promotion of outstanding individuals regardless of wider factors. Alongside which there will be a focus on repealing “hate” speech laws and the enshrining of free speech, a la first amendment, into multiple countries statutes.

-

Finally I also expect as a response to overkill from the woke movement we will see (over time) the return of shame as a cultural norm.

And finally coming specifically to the core of social democracy – the bureaucratic welfare state we know the current model is unsustainable and yet the cosmopolitan liberals at best tinker or at worst do nothing to it – because their leftist element don’t want change just higher salaries. And we know as a certainty it will need to change but what are the practical solutions I think each welfare state could go one of two ways; a) to one based on mutual aid (maybe seeing the return of friendly societies?) and community ownership, or b) a new great bargain of a Hayekian welfare state as originally thought up by Sam Bowman back in 2015. https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/philosophy/lets-have-a-hayekian-welfare-state/. Neither of this fits neatly into the cosmopolitan liberal box as they require are particularist, require thinking domestically not internationally and would necessarily require a conversation about who and what is and isn’t included in welfare coverage – a conversation about the degree to which a society is closed off from others.

And just thinking about these bullet points isn’t it clear there are ample opportunities for classical liberals/libertarians to get involved with the rightist end and influence the discussion and direction of debate. What does the cosmopolitan liberal politics offer – net zero by 2045 or 2050? DEI officers in every workplace?

A soft warm feeling because the New York Times tolerates your existence.

Looking to the future I think we as western societies face a choice, but it is not between Heaven or Hell (as the corporate press on both sides would have it) or as some classical liberals/libertarians would see it as between a sort of hipster Reaganism and a reactionary Corbynism. I think the choice western societies face is between becoming new Argentinas or new Singapores (and as of last December Argentina have chosen Singapore) and this is why so many (such as yourself Tyler) find themselves on a different political side than they expected. The establishment has failed across the West; it’s just that we keep forgetting the establishment is the cosmopolitan left.”

Venezuela under “Brutal Capitalism”

Jeffrey Clemens points us to some bonkers editorializing in the NYTimes coverage of the likely stolen election in Venezuela. The piece starts out reasonably enough:

Venezuela’s authoritarian leader, Nicolás Maduro, was declared the winner of the country’s tumultuous presidential election early Monday, despite enormous momentum from an opposition movement that had been convinced this was the year it would oust Mr. Maduro’s socialist-inspired party.

The vote was riddled with irregularities, and citizens were angrily protesting the government’s actions at voting centers even as the results were announced.

The term “socialist-inspired party” is peculiar. The party in question is the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela) and it’s founding principles state, “The party is constituted as a socialist party, and affirms that a socialist society is the only alternative to overcome the capitalist system.” So, I would have gone with ‘Mr. Maduro’s socialist party’. No matter, that’s not the big blunder. Later the piece says:

If the election decision holds and Mr. Maduro remains in power, he will carry Chavismo, the country’s socialist-inspired movement, into its third decade in Venezuela. Founded by former President Hugo Chávez, Mr. Maduro’s mentor, the movement initially promised to lift millions out of poverty.

For a time it did. But in recent years, the socialist model has given way to brutal capitalism, economists say, with a small state-connected minority controlling much of the nation’s wealth.

Venezuela is now governed by “brutal capitalism” under Maduro’s United Socialist Party!??? The NYTimes has lost touch with reality. From the link we find that what they mean is that some price and wage controls were lifted, including allowing dollars to be used because the bolívar, was “made worthless by hyperinflation,” and remittances from the United States were legalized:

NYTimes: With the country’s economy derailed by years of mismanagement and corruption, then pushed to the brink of collapse by American sanctions, Mr. Maduro was forced to relax the economic restraints that once defined his socialist government and provided the foundation for his political legitimacy.

Lifting some controls does not make Venezuela a capitalist country. Moreover, the lifting of controls led to improvements:

…Seeing shelves stocked again has also helped ease tensions in the capital, where anger over the lack of basic necessities has, over the years, helped fuel mass protests.

…The transformation also brought some relief to the millions of Venezuelans who have family abroad and can now receive, and spend, their dollar remittances on imported food.

Of course, the improvements were not equally shared. If you want to call unequal improvements, “brutal capitalism”. Well, I don’t think that’s useful but if you do so be sure to note that “under Maduro’s administration, more than 20,000 people have been subject to extrajudicial killings and seven million Venezuelans have been forced to flee the country.” (Wikipedia.) That’s brutal socialism.

Lastly, I don’t expect, the NYTimes to keep up on the latest counter-factual estimation techniques so I won’t ding them too much, but it’s clear that the Chavismo regime never lifted millions out of poverty. At best, poverty fell during the good years at the rate one would have expected from looking at similar countries. It’s the later rise in poverty which is unprecedented, as the NYTimes previously acknowledged.

My excellent Conversation with Alan Taylor, on American history

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler and Taylor take a walking tour of early history through North America covering the decisions, and ripples of those decisions, that shaped revolution and independence, including why Canada didn’t join the American revolution, why America in turn never conquered Canada, American’s early obsession with the collapse of the Republic, how democratic the Jacksonians were, Texas/Mexico tensions over escaped African American slaves, America’s refusal to recognize Cuban independence, how many American Tories went north post-revolution, Napoleon III’s war with Mexico, why the US Government considered attacking Canada after the Civil War, and much more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Now, here’s a quotation from your writings, page 37: “One of the great ironies of the American Revolution was that it led to virtually free land for settlers in British Canada while rendering land more expensive in the United States.” Could you explain that, please?

TAYLOR: Sure. The war was very expensive. All the states and the United States also incurred immense debts. How are you going to pay for that? This is the time when there’s no income tax, and the chief ways in which governments could raise money were on import duties and then on selling land. There was a lot of land, provided you could take it away from native peoples. All of the states and the United States were in the business of trying to sell land, but also they’re reliant within the states on these land taxes. All of these go up, then, to try to finance the war debt.

Whereas in British Canada, the British government is subsidizing the local government. They’re paying the full freight of it, which means that local taxes were much lower there. It also meant that they could afford to basically give away land to attract settlers. They had this notion that if we offer free land to Americans, they will want to leave that new American republic, move back into the British Empire, strengthen Canada, and provide a militia to defend it.

Substantive and interesting throughout. And can you guess what in his answers surprised me most?

Kamala Harris economic record

As a presidential candidate, Ms. Harris proposed replacing Mr. Trump’s 2017 tax cuts with a monthly refundable tax credit worth up to $500 for people earning less than $100,000. The policy, known as the LIFT the Middle Class Act, was unveiled in 2018 and aimed to address the rising cost of living by providing middle-class and working families with money to help pay for everyday expenses. She framed it as a way to close the wealth gap in the United States.

In 2019, Ms. Harris proposed increasing estate taxes on the wealthy to pay for a $300 billion plan to raise teacher salaries. In what was billed as the “largest federal investment in teacher pay in U.S. history,” the plan would have given the average teacher in America a $13,500 pay increase.

…Ms. Harris wanted to raise the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 35 percent, which is higher than the 28 percent that Mr. Biden had proposed.

And:

Ms. Harris made affordable housing a priority during her tenure in the Senate and her presidential campaign, but took a different approach. She proposed the Rent Relief Act, which would have provided refundable tax credits allowing renters who earn less than $100,000 to recoup housing costs in excess of 30 percent of their incomes.

To help the poorest, Ms. Harris also called for providing emergency relief funding for the homeless and for spending $100 billion in communities where people have traditionally been unable to get home loans because of discrimination.

And:

Ms. Harris, who served as California’s attorney general from 2011 to 2017, has also focused heavily on consumer protection. In 2016, she threatened Uber with legal action if the company did not remove driverless cars from the state’s roads.

After the 2008 financial crisis, she pulled California out of a national settlement with big banks, leveraging her power to wrest more money from major mortgage lenders. She later announced that California homeowners would receive $12 billion in mortgage relief under the settlement.

Here is the full NYT piece by Alan Rappeport.

Not Lost In Translation: How Barbarian Books Laid the Foundation for Japan’s Industrial Revoluton

Japan’s growth miracle after World War II is well known but that was Japan’s second miracle. The first was perhaps even more miraculous. At the end of the 19th century, under the Meiji Restoration, Japan transformed itself almost overnight from a peasant economy to an industrial powerhouse.

After centuries of resisting economic and social change, Japan transformed from a relatively poor, predominantly agricultural economy specialized in the exports of unprocessed, primary products to an economy specialized in the export of manufactures in under fifteen years.

In a remarkable new paper, Juhász, Sakabe, and Weinstein show how the key to this transformation was a massive effort to translate and codify technical information in the Japanese language. This state-led initiative made cutting-edge industrial knowledge accessible to Japanese entrepreneurs and workers in a way that was unparalleled among non-Western countries at the time.

Here’s an amazing graph which tells much of the story. In both 1870 and 1910 most of the technical knowledge of the world is in French, English, Italian and German but look at what happens in Japan–basically no technical books in 1870 to on par with English in 1910. Moreover, no other country did this.

Translating a technical document today is much easier than in the past because the words already exist. Translating technical documents in the late 19th century, however, required the creation and standardization of entirely new words.

…the Institute of Barbarian Books (Bansho Torishirabesho)…was tasked with developing English-Japanese dictionaries to facilitate technical translations. This project was the first step in what would become a massive government effort to codify and absorb Western science. Linguists and lexicographers have written extensively on the difficulty of scientific translation, which explains why little codification of knowledge happened in languages other than English and its close cognates: French and German (c.f. Kokawa et al. 1994; Lippert 2001; Clark 2009). The linguistic problem was two-fold. First, no words existed in Japanese for canonical Industrial Revolution products such as the railroad, steam engine, or telegraph, and using phonetic representations of all untranslatable jargon in a technical book resulted in transliteration of the text, not translation. Second, translations needed to be standardized so that all translators would translate a given foreign word into the same Japanese one.

Solving these two problems became one of the Institute’s main objectives.

Here’s a graph showing the creation of new words in Japan by year. You can see the explosion in new words in the late 19th century. Note that this happened well after the Perry Mission. The words didn’t simply evolve, the authors argue new words were created as a form of industrial policy.

By the way, AstralCodexTen points us to an interesting biography of a translator at the time who works on economics books:

[Fukuzawa] makes great progress on a number of translations. Among them is the first Western economics book translated into Japanese. In the course of this work, he encounters difficulties with the concept of “competition.” He decides to coin a new Japanese word, kyoso, derived from the words for “race and fight.” His patron, a Confucian, is unimpressed with this translation. He suggests other renderings. Why not “love of the nation shown in connection with trade”? Or “open generosity from a merchant in times of national stress”? But Fukuzawa insists on kyoso, and now the word is the first result on Google Translate.

There is a lot more in this paper. In particular, showing how the translation of documents lead to productivity growth on an industry by industry basis and a demonstration of the importance of this mechanism for economic growth across the world.

The bottom line for me is this: What caused the industrial revolution is a perennial question–was it coal, freedom, literacy?–but this is the first paper which gives what I think is a truly compelling answer for one particular case. Japan’s rapid industrialization under the Meiji Restoration was driven by its unprecedented effort to translate, codify, and disseminate Western technical knowledge in the Japanese language.

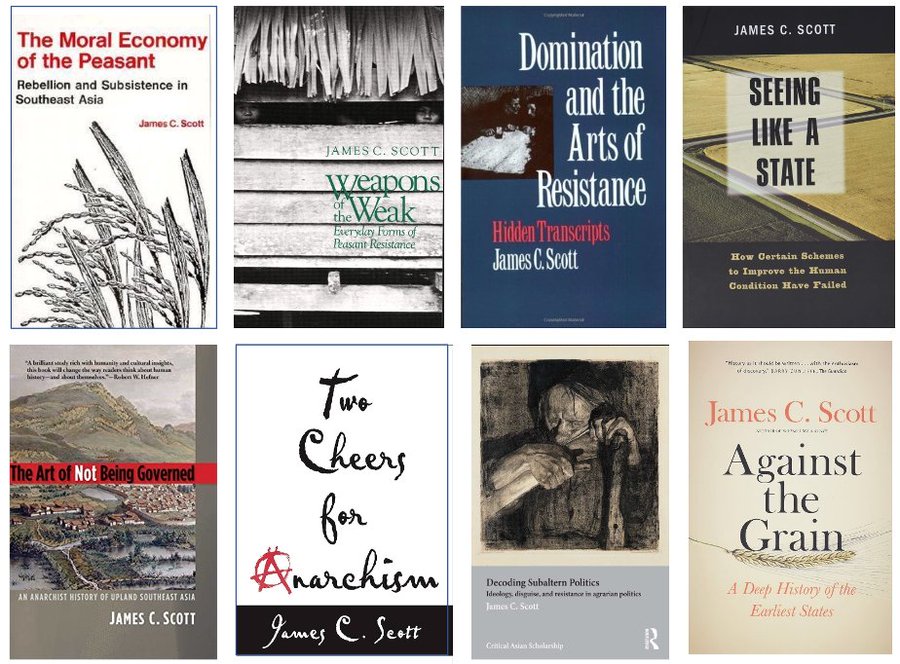

James Scott, RIP

The changes in vibes — why did they happen?

Clearly it has happened, and it has been accelerated and publicized by the Biden failings and the attempted Trump assassination. But it was already underway. If you need a single, unambiguous sign of it, I would cite MSNBC pulling off Morning Joe for a morning, for fear they would say something nasty about Trump.

Another way to put it is that Trump was a highly vulnerable, defeated President, facing numerous legal charges and indeed an actual felony conviction. Yet he now stands as a clear favorite in the next election. In conceptual terms, how exactly did that happen?

I had been thinking it would be a good cognitive test to ask people why they think the vibes have changed, and then to grade their answers for intelligence, insight, and intellectual honesty.

For instance, I used to read people arguing “Trump is popular because of racism,” but now that view is pretty clearly refuted, even if you think (as I do) that racism has some marginal impact on his support. Or other people have attributed the development to “polarization.” Whether or not you agree with the polarization thesis, it begs the question here, as we could be polarized with Trump as a big underdog.

In any case, thought I should start this process by offering my answers. Here they are, in a series of bullet points:

1. Trump and his team understand that we now live in a world of social media. Only a modest part of the Democratic establishment has mastered the same.

2. The “Trumpian Right,” whether you agree with it or not, has been more intellectually alive and vital than the Progressive Left, at least during the last five years, maybe more. Being fully on the outs, those people were more free to be creative, noting that I am not equating creative with being correct.

3. The deindustrialization of America has mattered more than people expected at first, and has had longer legs, in terms of its impact on public opinion. I would say this one is squarely in the mainstream account of the matter.

4. Many Trumpian and MAGA messages have been more in vibe with the negative contagion effects of our recent times.

5. The Democrats made a big bet that trying to raise the status of blacks would be popular, but at best they had mixed results. Some part of this failing was due to racists, some part due to immigrants with their own concerns, and some part due simply to the unpopularity of the message.

6. The ongoing feminization of society has driven more and more men, including black and Latino men, into the Republican camp. The Democratic Party became too much the party of unmarried women.

7. The Obama administration brought, to some degree, both the reality and perception of being ruled by the intellectual class. People didn’t like that.

8. Democrats and leftists are in fact less happy as people than conservatives are, on average. Americans noticed this, if only subconsciously.

9. The relentlessly egalitarian message of Democrats is not so popular, and furthermore — since every claim must have messengers — it translates in lived practice into an “I am better than you all are” vibe. Americans noticed this, if only subconsciously.

10. The Woke gambit has proven deeply unpopular.

11. Trans support has not been a winning issue for Democrats, but it is hard for them to let it go.

12. Immigration at the border has in fact spun out of control, and that has been a key Trump issue from the beginning of his campaign. And I write this as a person who is very pro-immigration. You can imagine how the immigration skeptics feel.

13. Higher education has been a traditional Democratic stronghold, and it remains one. Yet its clout and credibility have fallen significantly in the last few years.

14. The Democrats made a big mistake going after “Big Tech.” It didn’t cost them many votes, rather money and social capital. Big Tech (most of all Facebook) was the Girardian sacrifice for the Trump victory in 2016, and all the Democrats achieved from that was a hollowing out of their own elite base.

15. Various developments in Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Israel did not help the Democratic cause. Inflation was very high, and real borrowing rates went up sharply. This is true, whether or not you think it is the fault of Biden, or Trump would have done better. Crypto came under attack. The pandemic story is complicated, and its politics would require a post of its own, but I don’t think it helped the Democrats, most of all because they ended up “owning” many of the longer-lasting school closures.

And we haven’t even gotten to “Defund the police,” the recurring rise of anti-Semitism on the left, and at least a half dozen other matters.

16. In very simple terms, you might say the Democrats have done a lot to make themselves unpopular, and not had much willingness to confront that. Their own messages make this hard to face up to, since they are supposed to be better people.

You might add to this:

17. Trump is funny (he is one of the great American comics in fact), and

18. Trump acts like a winner. Americans like this, and his response to the failed assassination attempt drove this point home.

19. Biden’s recent troubles, and the realization that he and his team had been running a con at least as big as the Trump one. It has become a trust issue, not only an age or cognition issue.

On the other side of the ledger, you might argue, as do many intelligent people, that the Democrats are better at technocracy, and also that Democrats are more respectful of traditional political processes, especially transitions after elections. I’m not here to debate those issues! I know many MAGA supporters are not convinced, most of all on the latter. I’ll simply note that, in the minds of many Americans, those factors do not necessarily outweigh #1-19.

And there you go.

Addendum: Of course there was and is plenty wrong with Trump and the Trump administration. But the purpose here is not to compare Biden and Trump, rather it is to see why the Democrats are not doing better. If your response to that question is to cite reasons why the Democrats are better than Trump…well then you are exactly part of the problem.

Matt Yglesias on neoliberalism and economic growth

And it’s worth asking: Is it true that since 1974, policy debate in the United States has been dominated by a “growth-at-all-costs” brand of “free-market fundamentalism”?

I don’t think that actually is true. Technically, the biggest pieces of environmental legislation passed just outside that window — the Clean Air Act in 1970, the Clean Water Act in 1972, and the Endangered Species Act in 1973. But it’s pretty clear that environmental regulation is a lot stricter in 2024 than it was in 1974. The Americans With Disabilities Act was passed in 1990. Land use regulation — which was explicitly called “growth control” when it was new — has grown dramatically stricter since the seventies.

The idea that for the last 50 years we’ve been on a manic quest for growth is confused. In reality, we’ve seen during that time period increasing levels of political influence wielded by people (mainly environmentalists and NIMBYs) who are skeptical of economic growth. It’s true, as skeptics of growth sometimes note, that internal policy disputes in the 1950s and 60s rarely featured pushback on the grounds of the necessity of focusing on economic growth. But that’s not because anti-growth sentiment was stronger in the past — it’s because back then there was almost no one in a position of power who was arguing for explicitly anti-growth policies. Degrowthers have obviously not dominated American politics since the 1970s — we have had economic growth — but growth has been slower because anti-growth ideas have gotten some real purchase over the last 50 years. The Hewlett thesis statement about this is backwards.

Here is the full post, gated but worth paying for.

My excellent Conversation with Brian Winter

Here is the video, audio, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

It’s not just the churrasco that made him fall in love with Brazil. Brian Winter has been studying and writing about Latin America for over 20 years. He’s been tracking the struggles and triumphs of the region as it’s dealt with decades of coups, violence, and shifting economics. His work offers a nuanced perspective on Latin America’s persistent challenges and remarkable resilience.

Together Brian and Tyler discuss the politics and economics of nearly every country from the equator down. They cover the future of migration into Brazil, what it’s doing right in agriculture, the cultural shift in race politics, crime in Rio and São Paulo, the effectiveness and future consequences of Bukele’s police state in El Salvador, the economic growth of Colombia despite continued violence, the prevalence of startups and psychoanalysis in Argentina, Uruguay’s reduction in poverty levels, the beautiful ugliness of Sao Paulo, where Brian will explore next, and more.

And here is one excerpt;

COWEN: What’s the economic geography of Brazil going to look like? All the wealth near Mato Grosso and the north just very, very poor? Or the north empties out? How’s that going to work? There used to be some modest degree of balance.

WINTER: That’s true. Most of the population in Brazil and the economic center, for sure, was in the southeast. That means, really, São Paulo state, which is about a quarter of Brazil’s population but roughly a third of its GDP. Rio as well, and the state of Minas Gerais, which has a name that tells its history. That means “general mines” in Portuguese. That’s the area where a lot of the gold came out of in the 18th and 19th centuries. That’s gone now, so it’s not as much of an economic pull.

You’re right, Tyler, though, that a lot of the real boom right now, the action, is in places like Mato Grosso, which is in the region of Brazil called the Central West. That’s soy country. I’m from Texas, and Mato Grosso is virtually indistinguishable from Texas these days. It’s hot. It’s flat. The crop, like I said, is soy. There’s cattle ranching as well.

Even the music — Brazil, as others have noted, has gone from being the country of bossa nova and the samba in the 1970s to being the country of sertanejo today. Sertanejo is a Brazilian cousin of country music with accordions, but it’s sung by people — men mostly — in jeans, big belt buckles, and cowboy hats. They’re importing that — not only that economic model but that lifestyle as well.

COWEN: What is the great Brazilian music of today? MPB is dead, right? So, what should someone listen to?

Recommended, interesting throughout.

The French left is now winning

This is a big surprise to many people, as in the first round the right was doing much better in terms of votes and seats. We’ll learn more soon, but in the meantime I am reminded of one of the paradoxes in the theory of expressive voting. You might want to send a protest vote, but you don’t want too many other people sending the same protest vote. For instance, some people voting for Ralph Nader didn’t really want him to win. And the same may be true for the French right. So the very show of force from the right, in the first round, may have limited their subsequent numbers. More generally, you could say that an equilibrium, when there is a lot of expressive voting, is super-sensitive to expectations about the voting behavior of others. Especially when the receives of the expressive votes come close to holding real power.

Do you know the apocryphal story of the economics department that wanted to decide, unanimously, to vote 18-3 on the tenure case of a junior professor? That was not allowed, and so everyone voted in favor.

I wonder what this all means for a possible Democratic mini-primary!?

What should I ask Christopher Kirchhoff?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. In case you do not know, Christopher self-describes as:

Christopher Kirchhoff is an expert in emerging technology who founded the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley office and has led teams for the President, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and CEO of Google. He recently worked special projects at Anthropic. Previously, Dr. Kirchhoff helped design and scale $1 billion in philanthropic programs at Schmidt Futures. He also founded and led the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley Office, Defense Innovation Unit X, which piloted flying cars and microsatellites in military missions and created a new acquisition pathway for start-ups now responsible for $70 billion dollars of technology acquisition. During the Obama Administration, he was Director for Strategic Planning at the National Security Council and the senior civilian advisor to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

I very much enjoyed his new book Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley are Transforming the Future of War, co-authored with Raj M. Shah. Here is his home page. The book just received a very strong review from the FT.

So what should I ask Christopher?

PR for the UK?

I say no, we have enough European governments with proportional representation already. Should not someone allow for the possibility of more decisive action?

Estimates are suggesting that Labour won two-thirds of the seats with one-third of the vote, more or less. So that induces the usual cries of misrepresentation of the electorate (it also reminds us that virtually all electoral systems are not “democratic” in the naive sense of that term). But Britain has many serious problems, and I would rather see one party given a decisive mandate to handle them. And I write that as someone who is not in general rooting for the Labour Party — virtually all of my favorite British politicians are Tories, even if I do not like what that party has become as a whole.

Contrast the British with the recent French election. The distribution of votes was not altogether dissimilar, but the Britsh have “a landslide,” while the French have a possibly ungovernable situation.

I do love checks and balances, but the UK needs to defeat NIMBY and fix the NHS. Now it is Labour’s turn to try. Here is a broad outline of Labour’s 100-day plan. Not exactly what I would choose (see Wooldridge at Bloomberg), but if they get two or three big things right the regime still could be a success.

Note that the margins for the Labour victorious seats are extremely low, which means there is an ongoing constraint on the exercise of government power. I am not so worried about an “elected dictatorship.” If anything, it may not be decisive enough.

Another consideration is that PR for the UK could end up meaning the rise of an Islamic party of some kind, of course with minority status. I suspect that would worsen rather than improve democratic discourse in Britain, and perhaps hinder immigrant assimilation as well. I don’t want that to happen, and so it is another reason why the UK should not switch to a PR system.

What should I ask Nate Silver?

Yes, I will be doing another Conversation with Nate, based in part on his new and forthcoming book On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything (I have just started it, but so far it is very good, dealing with issues of poker and also risk-taking more generally).

Here is my previous Conversation with Nate Silver. And please note I am not looking to ask him about the election. So what should I ask?