Category: Political Science

Nationalism in Online Games During War

We investigate how international conflicts impact the behavior of hostile nationals in online games. Utilizing data from the largest online chess platform, where players can see their opponents’ country flags, we observed behavioral responses based on the opponents’ nationality. Specifically, there is a notable decrease in the share of games played against hostile nationals, indicating a reluctance to engage. Additionally, players show different strategic adjustments: they opt for safer opening moves and exhibit higher persistence in games, evidenced by longer game durations and fewer resignations. This study provides unique insights into the impact of geopolitical conflicts on strategic interactions in an online setting, offering contributions to further understanding human behavior during international conflicts.

That is from a new paper by Eren Bilen, Nino Doghonadze, Robizon Khubulashvili, and David Smerdon. Imagine if there is some addition Sino-Indian conflict right before the Ding vs. Gukesh WCC match…

For the pointer I thank various MR readers.

The who and how of campaign spending on Meta

Trump targets horse riding, Biden targets football, and RFK Jr. targets comedy.

Trump also can claim Ted Nugent fans, here is the full story. Via A.

A theory of information, by Noah Smith

So here you go: a theory of how totalitarianism might naturally triumph. The basic idea is that when information is costly, liberal democracy wins because it gathers more and better information than closed societies, but when information is cheap, negative-sum information tournaments sap an increasingly large portion of a liberal society’s resources. Remember that I don’t believe this theory; I’m merely trying to formulate it.

Here is the full blog post, gated after some point.

The Sea Change on Crypto-Regulation

In the last few weeks there has been a sea change in crypto regulation:

1. Bitcoin spot ETFs were approved–reluctantly, after a 3-judge Federal Appeals court ruled unanimously that the SEC had acted arbitrarily and capriciously–but nevertheless opening Bitcoin holdings to institutional investors. Case in point, The State of Wisconsin bought Bitcoin ETFs for its pension fund.

2. In a very unusual move, SAB 121, was overturned by the House and then, even more surprisingly, overturned by the Senate including the votes of many Democrats. < href=”https://www.sec.gov/oca/staff-accounting-bulletin-121″>SAB 121 is an SEC staff accounting bulletin (not law but guidance) that said to banks if you hold crypto for your customers, i.e. a custody service, you must account for it on your balance sheet. This guidance does not apply to custody of any other asset. Essentially, SAB 121 made it prohibitive for banks to offer custody services for crypto because that service would then impact all kinds of risk and asset regulations on the bank. Aside from singling out crypto, the SEC is not a regulator of banks so this seemed like a regulatory overreach.

President Biden said he will veto but that is no longer certain. It wasn’t just crypto lobbying against SAB 121 but traditional banks. The banks point to the approval of Bitcoin ETFs saying, quite logically, why can’t we custody these ETFs the way we do every other ETF? Senate Majority leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., sometimes called Wall Street’s man in Washington, voted in favor of nullifying SAB 121. Schumer can read the room.

3. The House voted to ban the Fed from establishing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

4. The House approved a wide-ranging bill to (finally!) establish regulations for digital assets markets. The vote was 279-136 in favor with many Democrats crossing party lines to support it.

5. After saying nothing for months, usually a bad sign, the SEC approved Ethereum spot ETFs. On the surface, this might have seemed logically inevitable given the approval of Bitcoin spot ETFs but many people thought the SEC would do everything it could to find daylight between Bitcoin and ETH. Instead, it tacitly acknowledged that ETH is a commodity and not a security.

Why is this happening? I see three main factors at play. First, crypto is becoming integrated with traditional finance. As the big banks get involved, the politics around crypto are shifting. Second, crypto is becoming normalized. Ironically, the prosecution of Sam Bankman-Fried, Changpeng Zhao and manipulators like Avraham Eisenberg may have convinced some U.S. regulators that crypto doesn’t have to be destroyed, it can be tamed. Nakamoto might not be pleased but realistically this was the only option to move forward. Eventually, everyone wants to pay their mortgage. Third, Trump’s strong endorsement of crypto has alarmed the Biden administration. Most political issues are firmly divided along party lines, but crypto remains an open issue. With millions of crypto owners in the United States, a significant number are highly motivated to vote their wallets. Biden doesn’t want to give the crypto issue to Trump.

None of this means we are entering crypto Nirvana but as far as regulation is concerned a lot has changed in just a matter of weeks.

Full Disclosure: I am an advisor to several firms in the crypto space including MultiversX, Bluechip and 0L.

*Unit X*

The subtitle of this new and excellent book is How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley are Transforming the Art of War. It is written not by journalists but two insiders to the process, namely Raj M. Shah and Christopher Kirchoff. Here you can read about Eric Schmidt, Brendan McCord, Anduril, Palantir, and much more.

I am not yet finished with the book, in the meantime here is one short excerpt, one that sets the stage for much of what follows:

It turned out that before Silicon Valley tech could be used on the battlefield, we had to go to war to buy it. We had to hack the Pentagon itself — its archaic acquisition procedures, which prevent moving money at Silicon Valley speed. In Silicon Valley, deals are done in days. The eighteen- to twenty-four month process for finalizing contracts used by most of the Pentagon was a nonstarter. No startup CEO trying to book revenue can wait for the earth to circle the sun twice. We needed a new way.

And this bit:

Ukraine avoided power interruptions in part because its over-engineered power grid boasts twice the capacity that the country needs — ironically, the system was originally designed by the Soviets to withstand a NATO attack.

The authors understand both the worlds of tech and bureaucracy very well, kudos to them. Due out in July.

The Generalist interviews me

I was happy with how this turned out, here is one excerpt:

I think we’re overestimating the risks to American democracy. The intellectual class is way too pessimistic. They’re not used to it being rough and tumble, but it’s been that way for most of the country’s history. It’s correct to think that’s unpleasant. But by being polarized and shouting at each other, we actually resolve things and eventually move forward. Not always the right way. I don’t always like the decisions it makes. But I think American democracy is going to be fine.

Polarization has its benefits. In most cases, you say what you think, and sooner or later, someone wins. Abortion is very polarized, for example. I’m not saying which side you should think is correct, but states are re-examining it. Kansas recently voted to allow abortion, and Arizona is in the midst of a debate. Over time, it will be settled—one way or another. Slugging things out is underrated.

Meanwhile, being reasonable with your constituents is overrated. Look at Germany, which has non-ideological, non-polarized politics. They’ve gotten every decision wrong. Their whole strategy of buying cheap energy from Russia to sell to China was a huge blunder. They bet most of their economy on it, and neither of those two things will work out. They also have no military whatsoever. It’s not like, “Ok, they don’t spend enough.” They literally had troops that didn’t have rifles to train with and were forced to use broomsticks.

Germany is truly screwed and won’t face up to it. But when you listen to their politicians speak – and I do understand German – they always sound intelligent and reasonable. They could use a dose of polarization, but they’re afraid because of their history, which I get. But the more you look at their politics, the more you end up liking ours, I would say.

I would note that Germany’s various “centrist” or “coalition of the middle” regimes have brought us AfD, which is polarizing in the worst way and considered to be an extremist party worthy of being spied upon.

And this:

What craft are you spending a lifetime honing?

Shooting a basketball. I’ve done that for the longest, outside of eating and breathing. I’m just not very good at it.

I started doing it when I was about eight. We moved close to a house with a hoop, and all the other kids would gather there and play. It was a social thing, and I started doing it. I kept it going in all the different places I’ve lived. The only country I couldn’t keep the habit going was Germany. But when I was living in New Zealand, I made a special point of it. It’s good exercise, it’s relaxing, you get to be outside. It’s a little cold today, but I did it yesterday, and I’ll do it tomorrow.

It’s important to repeatedly do something you’re not that good at. Most successful people are good at what they do, but if that’s all they do, they lose humility. They find it harder to understand a big chunk of the world that doesn’t have their talent or is simply mediocre. It helps you keep things in perspective.

I’m not terrible at it. I have gotten better, even recently. But no one would say I’m really good.

Interesting throughout, as they like to say.

My excellent Conversation with Benjamin Moser

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Benjamin Moser is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer celebrated for his in-depth studies of literary and cultural figures such as Susan Sontag and Clarice Lispector. His latest book, which details a twenty-year love affair with the Dutch masters, is one of Tyler’s favorite books on art criticism ever.

Benjamin joined Tyler to discuss why Vermeer was almost forgotten, how Rembrandt was so productive, what auctions of the old masters reveals about current approaches to painting, why Dutch art hangs best in houses, what makes the Kunstmuseum in the Hague so special, why Dutch students won’t read older books, Benjamin’s favorite Dutch movie, the tensions within Dutch social tolerance, the joys of living in Utrecht, why Latin Americans make for harder interview subjects, whether Brasilia works as a city, why modernism persisted in Brazil, how to appreciate Clarice Lispector, Susan Sontag’s (waning) influence, V.S. Naipaul’s mentorship, Houston’s intellectual culture, what he’s learning next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: You once wrote about Susan Sontag, and I quote, “So much of Sontag’s best work concerns the ways we try, and fail, to see.” Please explain.

MOSER: This is what On Photography is about. This is what Against Interpretation is about in Sontag’s work. Of course, in my new book, The Upside-Down World, I talk about how I’m not really great at seeing, particularly. I’m not that visual. I’m a reader. I’m a bookworm. Often, when I’ve looked at paintings, I’ve realized how little I actually see. Sometimes I do feel embarrassed by it. You’ll read the label and it’ll be three sentences, and it’ll say like, A Man with a Dog. You’re like, “Oh, I didn’t even see the dog.” You know what I mean?

On these very basic levels, I just think, “Oh, if someone doesn’t point it out to me, I really don’t see.” I think that that was one of the fascinating things about Sontag, that she was not really able to see. She was actually quite terrible at seeing, and this was especially true in her relationships. She was very bad at seeing what other people were thinking and feeling.

I think because she was aware of that, she tried very hard to remedy it, but it’s just not something you can force. You can’t force yourself to like certain music or to like certain tastes that you might not actually like.

COWEN: What was Sontag most right about or most insightful about?

MOSER: I think this question of images — what images do — and photography and how representations, metaphors can pervert things. She had a very deep repulsion to photography. She really hated photography, and this is why a lot of photographers hated her because they felt this, even though she didn’t really say it. She really didn’t trust it. She really thought it was wicked. At the same time, for somebody who had a deficit, I guess you could say, in seeing, she really relied on it to understand the world.

I think that tension is very instructive for us, because now, she already says 50 years ago, “There are all these images. We don’t know what to do with them. We don’t know how to process them.” Forget AI, forget Russian trolls on Twitter. She uses this word I really like, hygiene, a lot. She talks about mental hygiene and how you can clean the rusty pipes in your brain. That’s why I think reading her helped me at least to understand a lot of what I’m seeing in the world.

COWEN: Do you think she will simply end up forgotten?

Again, I am happy to recommend Benjamin’s latest book The Upside-Down World: Meetings with Dutch Masters.

Free Trade with Free Nations

Alec Stapp points out that Canada is the only NATO country that has a free trade agreement with the United States. That’s quite remarkable if you think about it. NATO allies are bound by mutual defense commitments, support for military cooperation, and a dedication to democratic principles. Despite these shared commitments, the U.S. still enforces tariffs and quotas on our NATO allies including France, Germany, the UK, Denmark, Portugal, and Spain. This is like getting married and not having a joint checking account. If they are good enough partners to commit to their defense then surely NATO allies are good enough partners to commit to free trade?

Free trade enhances the economic strength of countries, thus free trade should be a strategic asset in self-defense. Let’s be rich and safe together.

There are many reasons to have free trade agreements with countries that we don’t have a defense pact with but free trade with free nations should be a minimum standard. It’s not just the United States, of course, NATO allies don’t all have free trade agreements with fellow NATO members. So how about a North-Atlantic Trade Organization? You could call it NATO for short.

What should I ask Velina Tchakarova?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. She runs a geopolitics firm, hails from Bulgaria, is in my view broadly classical liberal, focuses on conflict in Eastern Europe and Ukraine, and is very active on Twitter.

Here is Velina on LinkedIn. She does not seem crazy.

So what should I ask her?

My Conversation with the excellent Coleman Hughes

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Coleman and Tyler explore the implications of colorblindness, including whether jazz would’ve been created in a color-blind society, how easy it is to disentangle race and culture, whether we should also try to be ‘autism-blind’, and Coleman’s personal experience with lookism and ageism. They also discuss what Coleman’s learned from J.J. Johnson, the hardest thing about performing the trombone, playing sets in the Charles Mingus Big Band as a teenager, whether Billy Joel is any good, what reservations he has about his conservative fans, why the Beastie Boys are overrated, what he’s learned from Noam Dworman, why Interstellar is Chris Nolan’s masterpiece, the Coleman Hughes production function, why political debate is so toxic, what he’ll do next, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: How was it you ended up playing trombone in Charles Mingus Big Band?

HUGHES: I participated in the Charles Mingus high school jazz festival, which they still do every year. It was new at the time. They invite bands from all around to audition, and they identify a handful of good soloists and let them sit in for one night with the band. I sat in with the band, and the band leader knew that I lived close by in New Jersey, and so essentially invited me to start playing with the band on Monday nights.

I was probably 16 or 17 at this point, so I would take the NJ Transit into New York City on a Monday night, play two sets with the Mingus Band sitting next to people that had been my idols and were now my mentors — people like Ku-umba Frank Lacy, who is a fantastic trombone player; played with Art Blakey and D’Angelo and so forth. Then I would go home at midnight and go to school on Tuesday morning.

COWEN: Why is the music of Charles Mingus special in jazz? Because it is to me, but how would you articulate what it is for you?

Here is another:

COWEN: If I understand you correctly, you’re also suggesting in our private lives we should be color-blind.

HUGHES: Yes. Broadly, yes. Or we should try to be.

COWEN: We should try to be. This is where I might not agree with you. So I find if I look at media, I look at social media, I see a dispute — I think 100 percent of the time I agree with Coleman, pretty much, on these race-related matters. In private lives, I’m less sure.

Let me ask you a question.

HUGHES: Sure.

COWEN: Could jazz music have been created in a color-blind America?

HUGHES: Could it have been created in a color-blind America — in what sense do you mean that question?

COWEN: It seems there’s a lot of cultural creativity. One issue is it may have required some hardship, but that’s not my point. It requires some sense of a cultural identity to motivate it — that the people making it want to express something about their lives, their history, their communities. And to them it’s not color-blind.

HUGHES: Interesting. My counterargument to that would be, insofar as I understand the early history of jazz, it was heavily more racially integrated than American society was at that time. In the sense that the culture of jazz music as it existed in, say, New Orleans and New York City was many, many decades ahead of the curve in terms of its attitudes towards how people should live racially: interracial friendship, interracial relationship, etc. Yes, I’d argue the ethos of jazz was more color-blind, in my sense, than the American average at the time.

COWEN: But maybe there’s some portfolio effect here. So yes, Benny Goodman hires Teddy Wilson to play for him. Teddy Wilson was black, as I’m sure you know. And that works marvelously well. It’s just good for the world that Benny Goodman does this.

Can it still not be the case that Teddy Wilson is pulling from something deep in his being, in his soul — about his racial experience, his upbringing, the people he’s known — and that that’s where a lot of the expression in the music comes from? That is most decidedly not color-blind, even though we would all endorse the fact that Benny Goodman was willing to hire Teddy Wilson.

HUGHES: Yes. Maybe — I’d argue it may not be culture-blind, though it probably is color-blind, in the sense that black Americans don’t just represent a race. That’s what a black American would have in common — that’s what I would have in common with someone from Ethiopia, is that we’re broadly of the same “race.” We are not at all of the same culture.

To the extent that there is something called “African American culture,” which I believe that there is, which has had many wonderful products, including jazz and hip-hop — yes, then I’m perfectly willing to concede that that’s a cultural product in the same way that, say, country music is like a product of broadly Southern culture.

COWEN: But then here’s my worry a bit. You’re going to have people privately putting out cultural visions in the public sphere through music, television, novels — a thousand ways — and those will inevitably be somewhat political once they’re cultural visions. So these other visions will be out there, and a lot of them you’re going to disagree with. It might be fine to say, “It would be better if we were all much more color-blind.” But given these other non-color-blind visions are out there, do you not have to, in some sense, counter them by not being so color-blind yourself and say, “Well, here’s a better way to think about the black or African American or Ethiopian or whatever identity”?

Interesting throughout.

Trump and the Fed

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

Trump advisers have been drafting plans to limit significantly the operating autonomy of the Fed. The Trump campaign has disavowed these plans, but the general ideas have been spreading in Republican circles, as evidenced by the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 report. Trump himself has called for a weaker dollar policy, which could not be carried out without some degree of Fed cooperation. As a former businessman and real-estate developer, Trump seems to care most about interest rates, banking and currencies.

One concrete proposal reported in the Wall Street Journal would require the Fed to informally consult with the president on decisions concerning interest rates and other major aspects of monetary policy. That would make it harder for the central bank to commit to a stated policy of disinflation, since the ongoing influence of the president would be a wild card in the decision. Presidents would likely give more consideration to their own reelection prospects than to the advice of the Fed staff. Further confusion would result from the reality that the responsibility of the president in these matters simply would not be clear.

It’s important not to be naïve: Regardless of who is in the White House, the Fed already cares what the president and Congress think, as its future independence is never guaranteed. Still, explicit consultation would undercut the coherence of the decision-making process within the Fed itself and send a negative signal to investors. There is no upside from this approach.

There is much more at the link.

Trade reform and economic growth

From the excellent Doug Irwin:

Do trade reforms that significantly reduce import barriers lead to faster economic growth? In the twenty-five years since Rodríguez and Rodrik’s (2000) critical survey of empirical work on this question, new research has tried to overcome the various methodological problems that have plagued previous attempts to provide a convincing answer. I examine three strands of recent work on this issue: cross-country regressions focusing on within-country growth, synthetic control methods on specific reform episodes, and empirical country studies looking at the channels through which lower trade barriers may increase productivity. A consistent finding is that trade reforms have had a positive impact on economic growth, on average, although the effect is heterogeneous across countries. Overall, these research findings should temper some of the previous agnosticism about the empirical link between trade reform and economic performance.

Here is my much earlier CWT with Doug Irwin.

Four Thousand Years of Egyptian Women Pictured

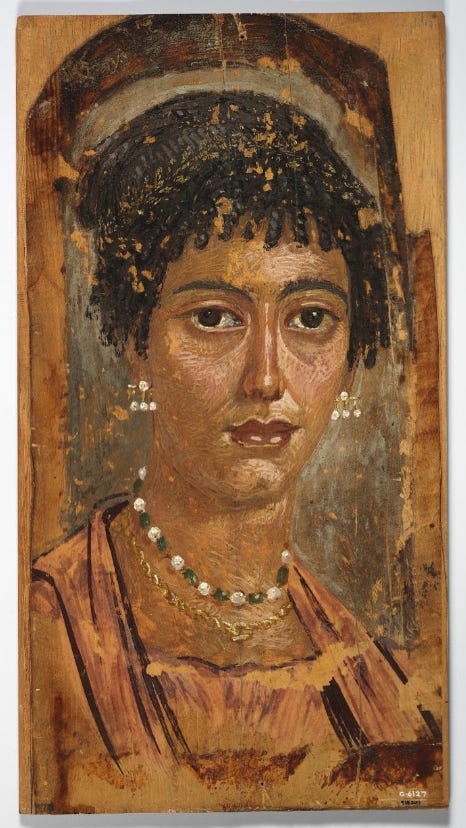

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

In an excellent, deep-dive Alice Evans looks at patriarchy in Egypt using pictures drawn from four thousand years of history. Here are three examples.

A wealthy woman, shown at right circa 116 CE. Unveiled, immodest, looking out at the world. A person to be reckoned with.

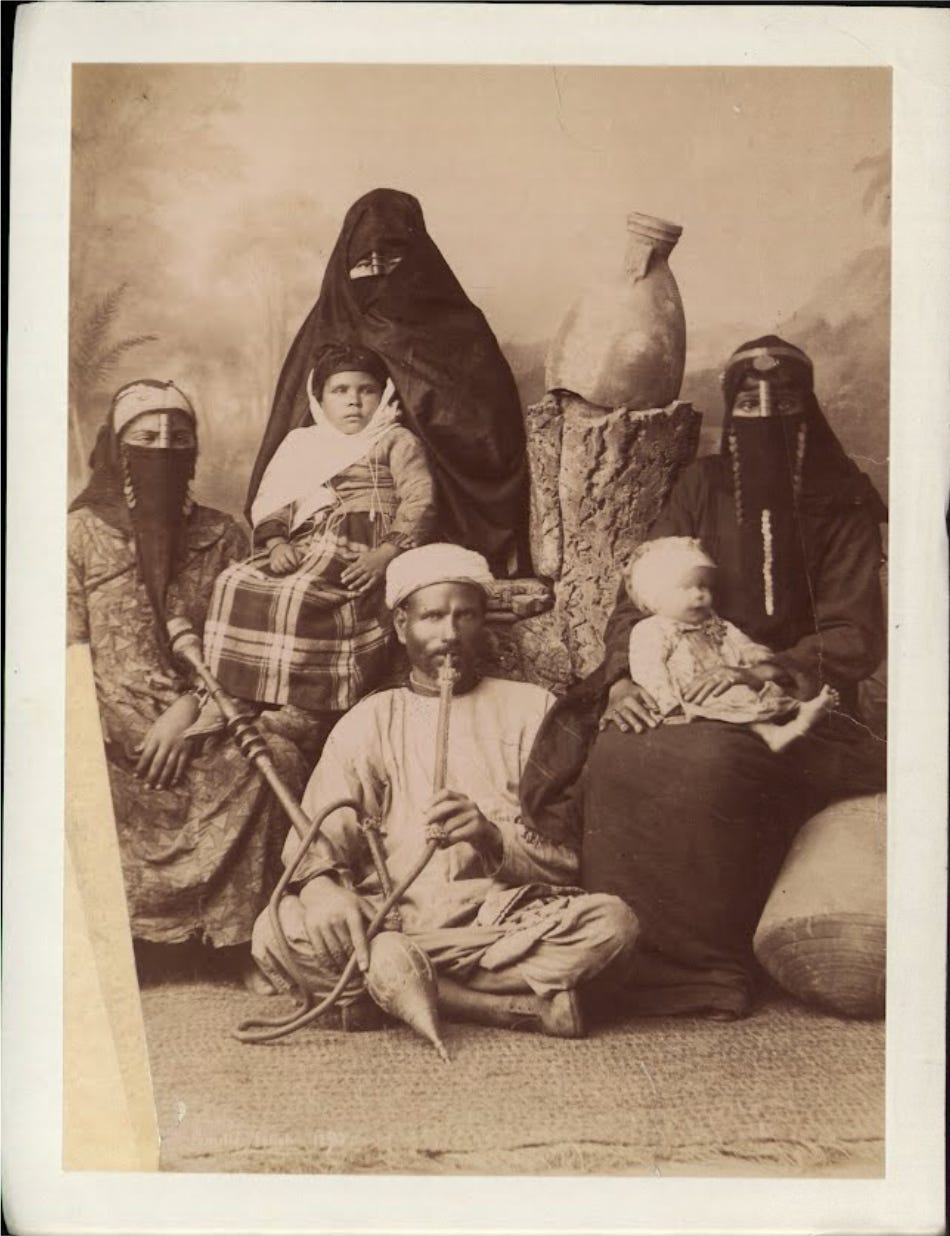

After the Arab conquests, pictures of people in general disappear, and there are no books written by women. With the dawn of photography in the 19th century we see (at left) what was probably typical, veiled women, and very few women on the street.

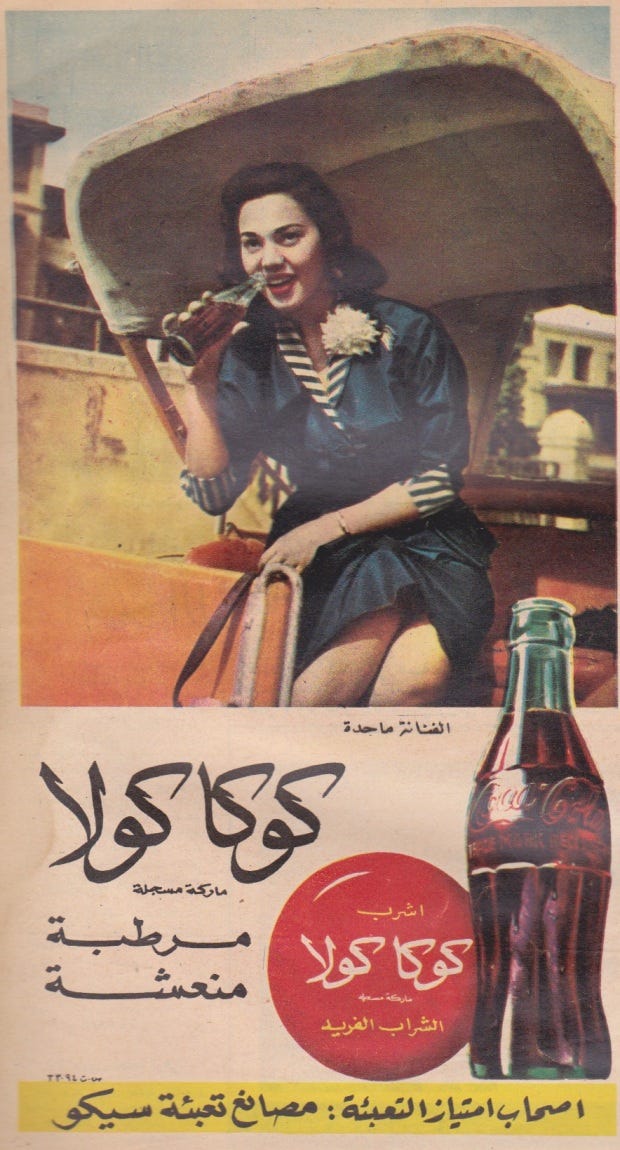

In the 1950s and 1970s we see a remarkable revitalization and liberalization noted most evidently in advertisements (advertisers being careful not to offend). Note the bare legs and the fact that many advertisements are directed at women (below)

This period culminates in a remarkable video unearthed by Evans of Nasser in 1958 openly laughing at the idea that women should or could be required to veil in public. Worth watching.

In the 1980s, however, it all ends.

Egyptians who came of age in the 1950s and ‘60s experienced national independence, social mobility and new economic opportunities. By the 1980s, economic progress was grinding down. Egypt’s purchasing power was plummeting. Middle class families could no longer afford basic goods, nor could the state provide.

As observed by Galal Amin,

“When the economy started to slacken in the early 1980s, accompanied by the fall in oil prices and the resulting decline in work opportunities in the Gulf, many of the aspirations built up in the 1970s were suddenly seen to be unrealistic and intense feelings of frustration followed”.

‘Western modernisation’ became discredited by economic stagnation and defeat by Israel. In Egypt, clerics equated modernity with a rejection of Islam and declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Islamic preachers called on men to restore order and piety (i.e., female seclusion). Frustrated graduates, struggling to find white collar work, found solace in religion, whilst many ordinary people turned to the Muslim Brotherhood for social services and righteous purpose.

That’s just a brief look at a much longer and fascinating post.

Do protests matter?

Only rarely:

Recent social movements stand out by their spontaneous nature and lack of stable leadership, raising doubts on their ability to generate political change. This article provides systematic evidence on the effects of protests on public opinion and political attitudes. Drawing on a database covering the quasi-universe of protests held in the United States, we identify 14 social movements that took place from 2017 to 2022, covering topics related to environmental protection, gender equality, gun control, immigration, national and international politics, and racial issues. We use Twitter data, Google search volumes, and high-frequency surveys to track the evolution of online interest, policy views, and vote intentions before and after the outset of each movement. Combining national-level event studies with difference-in-differences designs exploiting variation in local protest intensity, we find that protests generate substantial internet activity but have limited effects on political attitudes. Except for the Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd, which shifted views on racial discrimination and increased votes for the Democrats, we estimate precise null effects of protests on public opinion and electoral behavior.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Amory Gethin and Vincent Pons.

My excellent Conversation with Peter Thiel

Here is the audio, video, and transcript, along with almost thirty minutes of audience questions, filmed in Miami. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler and Peter Thiel dive deep into the complexities of political theology, including why it’s a concept we still need today, why Peter’s against Calvinism (and rationalism), whether the Old Testament should lead us to be woke, why Carl Schmitt is enjoying a resurgence, whether we’re entering a new age of millenarian thought, the one existential risk Peter thinks we’re overlooking, why everyone just muddling through leads to disaster, the role of the katechon, the political vision in Shakespeare, how AI will affect the influence of wordcels, Straussian messages in the Bible, what worries Peter about Miami, and more.

Here is an excerpt:

COWEN: Let’s say you’re trying to track the probability that the Western world and its allies somehow muddle through, and just keep on muddling through. What variable or variables do you look at to try to track or estimate that? What do you watch?

THIEL: Well, I don’t think it’s a really empirical question. If you could convince me that it was empirical, and you’d say, “These are the variables we should pay attention to” — if I agreed with that frame, you’ve already won half the argument. It’d be like variables . . . Well, the sun has risen and set every day, so it’ll probably keep doing that, so we shouldn’t worry. Or the planet has always muddled through, so Greta’s wrong, and we shouldn’t really pay attention to her. I’m sympathetic to not paying attention to her, but I don’t think this is a great argument.

Of course, if we think about the globalization project of the post–Cold War period where, in some sense, globalization just happens, there’s going to be more movement of goods and people and ideas and money, and we’re going to become this more peaceful, better-integrated world. You don’t need to sweat the details. We’re just going to muddle through.

Then, in my telling, there were a lot of things around that story that went very haywire. One simple version is, the US-China thing hasn’t quite worked the way Fukuyama and all these people envisioned it back in 1989. I think one could have figured this out much earlier if we had not been told, “You’re just going to muddle through.” The alarm bells would’ve gone off much sooner.

Maybe globalization is leading towards a neoliberal paradise. Maybe it’s leading to the totalitarian state of the Antichrist. Let’s say it’s not a very empirical argument, but if someone like you didn’t ask questions about muddling through, I’d be so much — like an optimistic boomer libertarian like you stop asking questions about muddling through, I’d be so much more assured, so much more hopeful.

COWEN: Are you saying it’s ultimately a metaphysical question rather than an empirical question?

THIEL: I don’t think it’s metaphysical, but it’s somewhat analytic.

COWEN: And moral, even. You’re laying down some duty by talking about muddling through.

THIEL: Well, it does tie into all these bigger questions. I don’t think that if we had a one-world state, this would automatically be for the best. I’m not sure that if we do a classical liberal or libertarian intuition on this, it would be maybe the absolute power that a one-world state would corrupt absolutely. I don’t think the libertarians were critical enough of it the last 20 or 30 years, so there was some way they didn’t believe their own theories. They didn’t connect things enough. I don’t know if I’d say that’s a moral failure, but there was some failure of the imagination.

COWEN: This multi-pronged skepticism about muddling through — would you say that’s your actual real political theology if we got into the bottom of this now?

THIEL: Whenever people think you can just muddle through, you’re probably set up for some kind of disaster. That’s fair. It’s not as positive as an agenda, but I always think . . .

One of my chapters in the Zero to One book was, “You are not a lottery ticket.” The basic advice is, if you’re an investor and you can just think, “Okay, I’m just muddling through as an investor here. I have no idea what to invest in. There are all these people. I can’t pay attention to any of them. I’m just going to write checks to everyone, make them go away. I’m just going to set up a desk somewhere here on South Beach, and I’m going to give a check to everyone who comes up to the desk, or not everybody. It’s just some writing lottery tickets.”

That’s just a formula for losing all your money. The place where I react so violently to the muddling through — again, we’re just not thinking. It can be Calvinist. It can be rationalist. It’s anti-intellectual. It’s not thinking about things.

Interesting throughout, definitely recommended. You may recall that the very first CWT episode (2015!) was with Peter, that is here.