Category: Science

The economics of compensated pregnancy surrogates, and who wants surrogates?

From Anemona Hartecollis, here are some interesting points:

Agencies prefer to contract with surrogates who are married with children, because they have a proven ability to have a healthy baby and are less likely to have second thoughts about giving up the child.

Conversely, gay couples are popular among surrogates. “Most of my surrogates want same-sex couples,” said Darlene Pinkerton, the owner of A Perfect Match, the agency in San Diego that Mr. Hoylman used. Women unable to become pregnant often go through feelings of jealousy and loss, she said. But with gay men, that is not part of the dynamic, so “the experience is really positive for the surrogate.”

Or as her husband, Tom, a third-party reproductive lawyer, put it, “Imagine instead of just having one husband doting on you, you have three guys now sending you flowers.”

The piece is interesting throughout.

The biggest problem with Swiss immigration restrictions

Switzerland really does produce global tfp, Tim Berners-Lee being the most obvious example, not to mention CERN, particle colliders, and pharmaceuticals:

The outcome of an ill-conceived referendum on 9 February against ‘mass immigration’ threatens to spoil Switzerland’s beautiful science landscape (see page 277).

The full story is here. For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

Collaborating With People Like Me: Ethnic co-authorship within the US

That is the new NBER paper by Richard B. Freeman and Wei Huang and it is an object lesson in the benefits of cross-cultural collaboration:

This study examines the ethnic identify of the authors of over 1.5 million scientific papers written solely in the US from 1985 to 2008. In this period the proportion of US-based authors with English and European names fell while the proportion of US-based authors with names from China and other developing countries increased. The evidence shows that persons of similar ethnicity co- author together more frequently than can be explained by chance given their proportions in the population of authors. This homophily in research collaborations is associated with weaker scientific contributions. Researchers with weaker past publication records are more likely to write with members of ethnicity than other researchers. Papers with greater homophily tend to be published in lower impact journals and to receive fewer citations than others, even holding fixed the previous publishing performance of the authors. Going beyond ethnic homophily, we find that papers with more authors in more locations and with longer lists of references tend to be published in relatively high impact journals and to receive more citations than other papers. These findings and those on homophily suggest that diversity in inputs into papers leads to greater contributions to science, as measured by impact factors and citations.

I can think of at least two ways of interpreting these results. First, there are research profit opportunities from finding talented foreign collaborators, who perhaps are still undervalued in their home environments, relative to their total potential global productivity. Second, the globalization of your connections proxies for how elite you are, even after adjusting for other measures of researcher quality.

Do any of you find ungated versions?

Jugaad sentences to ponder

The budget of India’s Mars mission, by contrast, was just three-quarters of the $100 million that Hollywood spent on last year’s space-based hit, “Gravity.”

There is more here.

Robert Gordon’s sequel paper on the great stagnation

You will find his NBER paper here, in which he responds to critics and outlines his core argument that U.S. growth is doomed to be slow and subpar for a long time to come. There is no point in summarizing this already-familiar debate, so let’s cut straight to the chase:

1. I agree with a great deal of this paper, to say the least, especially when it is compared to previous mainstream opinion on these topics. My favorite parts are his discussions of how multi-faceted were the waves of earlier progress starting in the 19th century, compared to some of the more recent and weaker tech revolutions. That said, in some key ways this piece falls short of meeting the standards of reasoned argumentation.

2. The single biggest question is how much the United States will be able to draw upon innovation from other countries, over the next say 40 years. Gordon doesn’t discuss this in a serious way. The rest of his paper simply lists a bunch of pessimistic factors (valid worries, I might add) and then declares he can’t think of anything else that might turn them around. Maybe that should shift your “p,” but one’s own failure to imagine shouldn’t imply a very firm conclusion about impossibilities.

3. There is a key passage on p.26: “My forecast of 1.3 percent annual total-economy productivity growth in the future does not require any foresight beyond suggesting that the past 40 years are a more relevant benchmark of feasible productivity growth than the 80 years of before 1972.” Fair enough, but how about looking at the last 120 years or last 120,000 years for that matter? The overall pattern is lots of pauses, followed by eventual new bursts of progress. That’s no proof of a future subsequent burst of progress, but so far history is not on the side of the long-term tech pessimists. It may be on the side of the short-term tech pessimists, at least for a while. Gordon, in 2003, wrote rather wisely: “But is it possible to be so sure which decades into the past are relevant for predictions…”

4. Gordon doesn’t know much about the literature on driverless vehicles and their potential, and yet he escalates his rhetoric to the point of giving the reader the impression that he approaches the entire question of tech progress with simple irritation: “This category of future progress is demoted to last place because it offers benefits that are so minor [compared to cars]…”

5. Advances in the biosciences are dismissed in two short paragraphs. For sure, I am myself somewhat in tune with the pessimistic perspective here. I think these advances were way over-promised and still may take longer than people think. Still, Gordon doesn’t offer any argument. His first sentence of that brief section says it all: “Future advances in medicine related to the genome have already proved to be disappointing.” This is a simple confusion of past and future tense.

7. Gordon still fails to credit the originators of the growth slowdown idea, as applied to contemporary times, namely Michael Mandel and Peter Thiel. The first sentence of his paper reads: “A controversy about the future of U.S. economic growth was ignited by my paper released in late summer 2012.” I would add, perhaps with a bit of peevishness, that a lot of the actual debate was kicked off by my own The Great Stagnation, published in January of 2011 and which was covered and commented on extensively. (And which by the way was dedicated to Mandel and Thiel, as well as citing them.) And if I did not credit Gordon more aggressively at that time, it is because I was all too well aware of his 2003 essay, “Exploding Productivity Growth,” the contents of which I do not need to relate any further but if you wish read at the link.

Gordon would do well to reflect a little more deeply on how and why he has changed his mind over the last ten years and what this implies for when a bit more agnosticism would be appropriate.

Addendum: I agree with Kevin Drum. Matt Yglesias comments too.

Is Robert Gordon underestimating the progress of automation?

In his recent NBER working paper, Robert Gordon wrote:

This lack of multitasking ability is dismissed by the robot enthusiasts – just wait, it is coming. Soon our robots will not only be able to win at Jeopardy but also will be able to check in your bags at the sky cap station at the airport, thus displacing the skycaps. But the physical tasks that humans can do are unlikely to be replaced in the next several decades by robots. Surely multiple-function robots will be developed, but it will be a long and gradual process before robots outside of the manufacturing and wholesaling sectors become a significant factor in replacing human jobs in the service or construction sectors.

So how is it with those skycaps? I queried Air Genius Gary Leff and he wrote this back to me:

There are still people picking up/loading bags onto the planes, but —

American Airlines has tested self-tagging of bags in Boston, Austin, and Orlando

http://boardingarea.com/aadvantagegeek/2012/11/14/american-airlines-orlando-mco-self-tagging-tag-bag-luggage-system-check-i/Qantas has permanent bag tags that work with RFID readers at the airport, you check in online and drop your bag at the bag drop and leave. This works for their Australian domestic flights. (I do have a “Q Bag Tag”)

http://www.qantas.com.au/travel/airlines/q-bag-tag/global/enBritish Airways is trialing an end to paper tags, they began with Microsoft employees in Seattle this past fall

http://boardingarea.com/viewfromthewing/2013/11/07/british-airways-new-electronic-baggage-tags/Brussels Airlines on intra-European flights departing Brussels

http://brusselsairlines.prezly.com/brussels-airport-and-brussels-airlines-test-automated-self-baggage-drop-off-BWI is working on their baggage systems to accommodate self-checking of bags

http://www.capitalgazette.com/news/general_assembly/bwi-moving-forward-with-new-hotel-self-bag-check-in/

And that required no more than a few minutes thought from Gary.

Joseph Nocera calls me on the phone

On Friday, I called Tyler Cowen, the George Mason University economist (and a contributor to The New York Times) to ask what he thought about the relationship between technological innovation and jobs. He told me that he mostly agreed with Brynjolfsson and McAfee about the future, though he disagreed with their assessment of the past. (One of his recent books is titled “The Great Stagnation.”)

Yes, he said, technology would replace humans for certain kinds of jobs, but he could also envision growth in the service sector. “The jobs will be better than they sound,” he said. “A lot of them will require skill and training, and will also pay well. I think we’ll get to driverless cars and much better versions of Siri fairly soon,” he added. “That will make the rate of labor force participation go down.”

Then he chuckled. He had recently been in a meeting with someone, explaining his views. “So what you’re saying,” the man concluded, “is that the pessimists are right. But it’s going to be much better than they think.”

Facebook is introducing more choices for gender identification

You don’t have to be just male or female on Facebook anymore. The social media giant is adding a customizable option with about 50 different terms people can use to identify their gender, as well as three preferred pronoun choices: him, her or them.

I’m all for this development, and I’ll note one extra thing: people who write on “the paradox of choice” are unlikely to ever use this as an example.

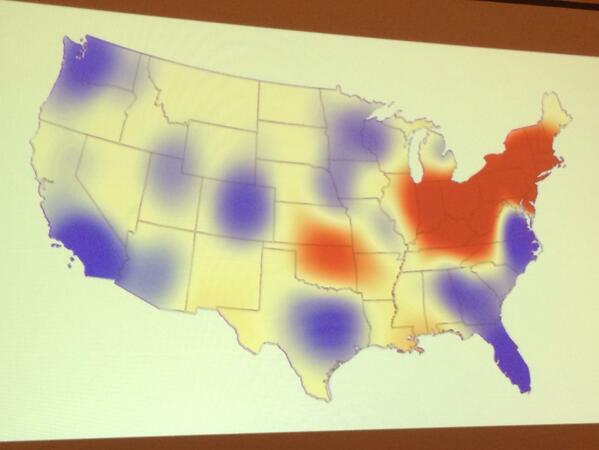

Personality by region

As indicated by words on blogs: red is high neurotic, blue is low. Highly speculative of course:

How beautiful is mathematics?

From James Gallagher of the BBC:

Mathematicians were shown “ugly” and “beautiful” equations while in a brain scanner at University College London.

The same emotional brain centres used to appreciate art were being activated by “beautiful” maths.

The researchers suggest there may be a neurobiological basis to beauty.

The likes of Euler’s identity or the Pythagorean identity are rarely mentioned in the same breath as the best of Mozart, Shakespeare and Van Gogh.

The study in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience gave 15 mathematicians 60 formula to rate.

Euler’s Identity is a particular favorite of mine, and indeed:

The more beautiful they rated the formula, the greater the surge in activity detected during the fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scans.

…To the untrained eye there may not be much beauty in Euler’s identity, but in the study it was the formula of choice for mathematicians.

Oh, and this:

In the study, mathematicians rated Srinivasa Ramanujan’s infinite series and Riemann’s functional equation as the ugliest of the formulae.

For the pointer I thank Joanna Syrda.

Are natural scientists smarter?

Social science professors at elite institutions are more likely to be religious and politically extreme than their counterparts in the natural sciences, argues a new paper in the Interdisciplinary Journal on Research and Religion. The reason? Natural scientists are just smarter, it says.

“There is sound evidence of a negative correlation between intelligence and religiosity and between intelligence and political extremism,” reads the paper, which examines existing data on academic scientists’ IQs by field, and on religious beliefs and political extremism among science professors in the U.S. and Britain. (An abstract of the paper is available here.) “Therefore the most probable reason behind elite social scientists being more religious than are elite physical scientists is that social scientists are less intelligent.”

The paper, written by Edward Dutton, adjunct professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Oulu, in Finland, and Richard Lynn, a retired professor of psychology from the University of Ulster, in Northern Ireland, who is known for his work on race and IQ, continues: “Intelligence is also a factor in interdisciplinary differences in political extremism, [with] physicists, who have high IQs, being among the least extreme and lower-IQ scholars being among the most extreme.”

There is more here, though I will note, without wishing to offend anyone in particular, that just about all of us are capable of being spectacularly dense, natural scientists included and these authors too. I believe these correlations, to the extent they are true, are better explained by sociological factors than by IQ. In the United States for instance various brands of humanities professors are in fact remarkably secular and I take this to be a stamp of a particular kind of affiliation to (and against) other social groups, not a sign of IQ in either direction. Note also that political extremism has to select against low IQ at some margins, if only because the extreme doctrine involves a complicated ideological apparatus of some sort rather than just “folk morality.”

By the way, here is Dutton’s earlier 2010 piece “Why did Jesus Go To Oxford University?” (pdf), which suggests the smarter and more creative students are more likely to have evangelical religious experience.

The UAE will deliver some governmental services by drone

The United Arab Emirates says it plans to use unmanned aerial drones to deliver official documents and packages to its citizens as part of efforts to upgrade government services.

…Local engineer Abdulrahman Alserkal, who designed the project, said fingerprint and eye-recognition security systems would be used to protect the drones and their cargo.

Gergawi said the drones would be tested for durability and efficiency in Dubai for six months, before being introduced across the UAE within a year. Services would initially include delivery of identity cards, driving licenses and other permits.

There is more here, hat tip to the excellent Mark Thorson.

If your parents died early, will you die early too?

But in fact the correlation of longevity between individual parents and children is very low. For the people dying in England in the period 1858-2012 with the rare surnames used in chapter 4, we can measure the correlation of longevity between fathers and sons for more than four thousand sons surviving until at least age 21. That correlation is only 0.13. If we take the average of both parents’ ages at death, that correlation increases to 0.26. But it is still low. In reality, your age at death is not strongly predictable from your parents’ age at death. All those saving more for retirement simply because both parents are fit, healthy, and in their nineties should stop immediately. Your expected additional longevity relative to the average is only three years.

That is from Greg Clark’s new and noteworthy The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility. Here is Kevin Drum on the book.

Who are the most overrated economists?

I was asked that question over lunch while visiting the PPE program at UNC, and my answer was this.

In general the market in ideas and reputations of economists works fairly well, at least in the United States. Nonetheless at any point in time, the most overrated economists are the most highly rated young empirical economists at the top schools.

Think of it this way. The half-life of a good empirical result is getting progressively shorter. Good empirical papers no longer stand as definitive accounts for fifteen years and sometimes not even for fifteen months. The science is getting better, but the individual economist is becoming less important, as we might expect from a growing division of labor. That is healthy, but it has implications for the distribution of reputation.

The total amount of repute and renown accorded to individual top young economists does not decline at the same rate that individual contributions become less important. That total amount of repute and renown at say Harvard, available to be doled out to the latest hot young economist, is fixed in the short run or may even be rising, due to the high returns on the school’s endowment.

So those economists end up individually overrated, even though as a whole they become more impressive over time.

Working backwards, one might be inclined to think old theorists and economists who have invented or fleshed out general methods are the most underrated.

First monkeys with customized mutations born

The ultimate potential of precision gene-editing techniques is beginning to be realised. Today, researchers in China report the first monkeys engineered with targeted mutations, an achievement that could be a stepping stone to making more realistic research models of human diseases.

Xingxu Huang, a geneticist at the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University in China, and his colleagues successfully engineered twin cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) with two targeted mutations using the CRISPR/Cas9 system — a technology that has taken the field of genetic engineering by storm in the past year. Researchers have leveraged the technique to disrupt genes in mice and rats, but until now none had succeeded in primates.

The article is here. Now solve for the equilibrium, as they like to say…

For the pointer I thank @autismcrisis.