Category: Science

Chat with James Pethokoukis on *Average is Over*

Here is one of several interesting bits:

Well the Brynjolfsson and McAffee book, “Race Against the Machine,” that’s a great book. It’s influenced my thinking. I just read their second forthcoming book, “The Second Machine Age.” They focus more on automation than I do and less on inequality and much less on social issues. But I think of myself as thinking along the same lines as they do. But they and I, we differ a lot about the past. So they don’t think the past has been a great stagnation. I agree with them a lot about the future, but disagree with them a lot about the past.

Gordon, I disagree with him about the future, but agree with him about the past. So Gordon, like me, sees a great stagnation. And he thinks it will never ever end. I think that’s crazy. Even if it were true, how would you know? But I see a lot of areas, not only artificial intelligence, but medicine and genomics, where the advances are not on the table now. But it’s hard to believe there’s not going to be a lot more coming. Science is very healthy. There’re new discoveries all the time. The lags are much longer than we’d like to think, but absolutely progress is not over, and we’re about to see a new wave of progress over the lifetimes of our children.

The full dialog is here.

My *New Yorker* interview on *Average is Over*

It was with Joshua Rothman, here is one bit:

The whole narrative you unfold—intelligent software, human-computer cooperation, deferring to our smartphones—sounds very futuristic. Do you think we’re living through a historically unprecedented period?

I don’t accept the view that this new era is so different from every time in the past. Consider the industrial revolution, which starts in Great Britain in the seventeen-seventies or seventeen-eighties. For a long time, you had rising inequality, fairly stagnant living standards, a lot of problems adjusting. Of course, we did eventually get over it in the longer run, and it was much better for everyone. But it took, arguably, fifty or sixty years for us to make that transition. I think this future wave of inequality, which is already underway, will be a lot like that. It will take us decades to make the transition. Those decades will bring a lot of problems. But I think that in the much longer run—which is not what the book is about—it will be much more positive than it will seem during the transition era. I think this period fits quite nicely with historical precedent.

There is also this:

In the U.S., New York City is probably the most unequal place we’ve got. And I find it striking how many people believe, first, that inequality is terrible, and that this vision for the future is horrible, and, at the same time, think, “Oh, I love New York City!”

We already have places with extreme inequality, but life there goes on, and we don’t recoil in horror. The non-wealthy parts of New York are very vital, and have the best of humanity in them. We have intuitions [about equality and inequality] that are derived from American post-war history. I don’t want to dismiss those intuitions altogether, but I think we need to be more skeptical of them.

India fact of the day

Drawn from a tweet:

At $72m, India’s mission to Mars less expensive than many NY/London apartments.

You can verify that Indian number here. How about some Mumbai buildings while we are at it?

Learning to Compete and Cooperate

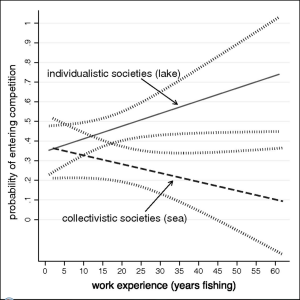

What drives individualism and competitiveness as opposed to collectivism and cooperation? Leibbrandt, Gneezy and List have a great paper studying this question with an ingenious  experiment. LGL study two types of fishermen in Northeastern Brazil. The two types live within ~50km of one another but one type are lake fishermen and the other sea fishermen. Lake fishing favors individual fisherman in small boats while sea fishing favors team production on larger boats.

experiment. LGL study two types of fishermen in Northeastern Brazil. The two types live within ~50km of one another but one type are lake fishermen and the other sea fishermen. Lake fishing favors individual fisherman in small boats while sea fishing favors team production on larger boats.

LGL ask the fisherman to participate in a simple experiment, throw 10 tennis balls into a bucket. The participants choose how they are paid, 1 monetary unit per successful attempt or 3 units per successful attempt if they have more successes than an unknown competitor (chosen randomly and without their knowledge to avoid social effects; in case of a tie they are paid 1 unit per success). Fishermen could earn 1-2 days of income for less than an hour of work depending on how successful they were and the payment scheme chosen.

Perhaps you won’t be too surprised to learn that 45.6% of the lake fishermen chose to compete compared with just 27.6% of the sea fishermen. What makes the paper great is all the secondary tests the authors do to understand this result at a deep level. The result, for example, is not due to differences in throwing ability or risk preferences.

You might suspect that the different choices about whether to compete or not are driven by cultural differences. But that too is incorrect. The authors, for example, show that women–who do not fish in either the sea or lake villages–do not show differences in the choices to compete (both chose to compete less than the men but at the same rates in lake or sea villages).

Instead, what the authors demonstrate is that differences in the choice to compete or not appear to be learned differences. First, the lake villagers who chose to compete are among the most successful lake fishermen–that is, they have learned that competition increases income. In the sea villages there is no correlation between choosing to compete and fishing income.

Instead, what the authors demonstrate is that differences in the choice to compete or not appear to be learned differences. First, the lake villagers who chose to compete are among the most successful lake fishermen–that is, they have learned that competition increases income. In the sea villages there is no correlation between choosing to compete and fishing income.

Finally, and most tellingly, there is a dose-response relationship between competition and learning. In particular, the choice to compete or not increases with fishing experience with the experienced lake fisherman choosing to compete more and the experienced sea fishermen choosing to compete less (as shown at left).

The paper appears on the surface to be affirming the importance of cultural differences and to be agreeing with the kind of literature that stresses the idea of self-interest and individualism as western and contingent. Yet, in fact, the paper is suggesting that at a deeper level so-called cultural differences may not be transmitted down through the generations but instead are learned responses to very particular production techniques. Note that such learned responses may change rapidly as production techniques change and that the sea and lake villages are both unusual in the modern world in relying on just one dominant production technique with few other options for learning.

More generally, learning needs to be added to incentives, genetics, and culture as an independent yet entangled determinant of choice.

Do children brought up in the same family share the same environmental influences?

Maybe not. Here is a fascinating 2011 paper (pdf) from Robert Plomin and Denise Daniels, and here is part of the abstract:

…environmental differences between children in the same family (called ‘‘nonshared environment’’) represent the major source of environmental variance for personality, psychopathology, and cognitive abilities. One example of the evidence that supports this conclusion involves correlations for pairs of adopted children reared in the same family from early in life. Because these children share family environment but not heredity, their correlation directly estimates the importance of shared family environment. For most psychological characteristics, correlations for adoptive ‘‘siblings’’ hover near zero, which implies that the relevant environmental influences are not shared by children in the same family. Although it has been thought that cognitive abilities represent an exception to this rule, recent data suggest that environmental variance that affects IQ is also of the nonshared variety after adolescence.

My favorite part of the paper is the section which discusses how siblings represents a non-shared environment for each other. For instance my sister grew up with a slightly younger brother and I grew up with…a slightly older sister, which is a somewhat different proposition.

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

What are the ethics of the cyborg cockroach? (Franz Kafka edition)

At the TEDx conference in Detroit last week, RoboRoach #12 scuttled across the exhibition floor, pursued not by an exterminator but by a gaggle of fascinated onlookers. Wearing a tiny backpack of microelectronics on its shell, the cockroach—a member of the Blaptica dubiaspecies—zigzagged along the corridor in a twitchy fashion, its direction controlled by the brush of a finger against an iPhone touch screen (as seen in video above).

RoboRoach #12 and its brethren are billed as a do-it-yourself neuroscience experiment that allows students to create their own “cyborg” insects. The roach was the main feature of the TEDx talk by Greg Gage and Tim Marzullo, co-founders of an educational company calledBackyard Brains. After a summer Kickstarter campaign raised enough money to let them hone their insect creation, the pair used the Detroit presentation to show it off and announce that starting in November, the company will, for $99, begin shipping live cockroaches across the nation, accompanied by a microelectronic hardware and surgical kits geared toward students as young as 10 years old.

And what is the problem exactly?

The roaches’ movements to the right or left are controlled by electrodes that feed into their antennae and receive signals by remote control—via the Bluetooth signals emitted by smartphones. To attach the device to the insect, students are instructed to douse the insect in ice water to “anesthetize” it, sand a patch of shell on its head so that the superglue and electrodes will stick, and then insert a groundwire into the insect’s thorax. Next, they must carefully trim the insect’s antennae, and insert silver electrodes into them. Ultimately, these wires receive electrical impulses from a circuit affixed to the insect’s back.

Gage says the roaches feel little pain from the stimulation, to which they quickly adapt. But the notion that the insects aren’t seriously harmed by having body parts cut off is “disingenuous,” says animal behavior scientist Jonathan Balcombe of the Humane Society University in Washington, D.C. “If it was discovered that a teacher was having students use magnifying glasses to burn ants and then look at their tissue, how would people react?”

The full story is here, interesting throughout and with a video too.

Trade, Development and Genetic Distance

Trade increases development but the main driver appears not to be comparative advantage and the standard microeconomic “gains from trade” but rather factors emphasized by Adam Smith and Paul Romer such as the increasing returns to scale that drives innovation and investment in R&D and also the ways in which trade increases exposure to and adoption of foreign ideas.

It’s much easier, however, to trade goods than ideas. The price of wheat shows strong convergence around the world by the 19th century but even simple ideas like hand-washing transmit much more slowly. Complex ideas like the rights of women, the rule of law or the corporate form transmit even more slowly. Thus, one of the barriers to development is barriers to the transmission of ideas.

Enrico Spolaore and Romain Wacziarg have done pioneering work uncovering some of the deep factors of development by using genetic distance as a measure of the difficulty of communicating ideas. Spolaore and Wacziarg have a short paper in Vox summarizing their methods and findings.

[G]enetic distance is like a molecular clock – it measures average separation times between populations. Therefore, genetic distance can be used as a summary statistic for divergence in all the traits that are transmitted with variation from one generation to the next over the long run, including divergence in cultural traits.

Our hypothesis is that, at a later stage, when populations enter into contact with each other, differences in those traits create barriers to exchange, communication, and imitation.

…Our barriers model implies that different development patterns across societies should depend not so much on the absolute genetic distance between them, but more on their relative genetic distance from the world’s technological frontier. For example, when studying the spread of the Industrial Revolution in Europe in the 19th century, what matters is not so much the absolute distance between the Greeks and the Italians, but rather how much closer Italians were to the English than the Greeks were. Indeed, we show that the magnitude of the effect of genetic distance relative to the technological frontier is about three times as large as that of absolute genetic distance. When including both measures in the regression, genetic distance relative to the frontier remains significant while absolute genetic distance becomes insignificantly different from zero. The effects are large in magnitude – a one-standard-deviation increase in genetic distance relative to the technological frontier (the US in the 20th century) is associated with an increase in the absolute difference in log income per capita of almost 29% of that variable’s standard deviation.

Our model implies that after a major innovation, such as the Industrial Revolution, the effect of genealogical distance should be pronounced, but that it should decline as more and more societies adopt the innovations of the technological frontier (which, in the 19th century, was the UK). These predictions are supported by the historical evidence. The figure below shows the standardised effects of genetic distance relative to the frontier for a common sample of 41 countries, for which data are available at all dates. The figure is consistent with our barriers model. As predicted, the effect of genetic distance – which is initially modest in 1820 – rises by around 75% to reach a peak in 1913, and declines thereafter.

Figure 1. Standardised effect of genetic distance over time, 1820-2005

Further small steps toward designer babies

A personal-genomics company in California has been awarded a broad U.S. patent for a technique that could be used in a fertility clinic to create babies with selected traits, as the frontiers of genetic enhancement continue to advance.

The patented process from 23andMe, whose main business is collecting DNA from customers and analyzing it to provide information about health and ancestry, could be employed to match the genetic profile of a would-be parent to that of donor sperm or eggs. In theory, this could lead to the advent of “designer babies,” a controversial idea where genes would be selected to boost the chances of a child having certain physical attributes, such as a particular eye or hair color.

The technique potentially could also be used to create healthier babies, by screening out donors with genes that are predisposed to disease, either on their own, or in combination with the recipient’s genes.

The awarding of the patent “is a massive addition to what is currently being done” in fertility clinics, said Sigrid Sterckx of the Bioethics Institute Ghent in Belgium, who co-wrote a commentary on the 23andMe patent in the journal Genetics in Medicine on Thursday. “It indicates a different attitude, not just about disease-related traits, but nondisease traits.” 23andMe, based in Mountain View, Calif., says that while its new patent encompasses trait selection in babies, through a tool called the Family Traits Inheritance Calculator, it has no plans to apply it to that end.

As I understand the article, this works only when there is a sperm or egg donor, although a potential marrying couple could use it ex ante (“come on Biff, let’s just try it, I’m just curious. I’ll always love you.”) My view has long been that most people, if they have the chance, are willing to embrace and also use eugenics, albeit with some reframing and rebranding. Eugenics was a very popular idea with Progressives earlier in the twentieth century, and also with economists (in particular, pdf), and ultimately the Nazi connection will be seen as a bump in the road. Competition with the Chinese will help push Americans toward this ideological shift. I am more skeptical myself, as I see greater value in the genetic outliers and I fear their disappearance or diminution. I also am relatively skeptical about the quality of the processes — legal and otherwise — which are likely to govern such experiments. In any case, you can think of this as the next step after “early intervention.” Why don’t we call it “very early intervention”?

The story is here, and if you need to get through the gate, enter “Gautam Naik”, the author of the article, into news.google.com.

My interview with Eric John Barker

It is here in excerpts, mostly about Average is Over, but with some twists, here is one part:

TC:…That’s right, and Obi-Wan also tells Luke, “Finish your training in the Dagobah system,” right? How many times did he tell him? Yoda tells him. Yoda. What does Luke do? He tells Yoda to get lost. So I think as humans we’re somewhat programmed to be a bit rebellious and to not want to be controlled, which is perfectly understandable given that others are trying to control us as often as they are. But that’s going to mean in those new settings, which we’ve never biologically evolved to handle, we’re going to screw up an awful lot. Just like Luke did not finish his training in the Dagobah system.

Eric’s very interesting blog you will find here.

Your robot anesthesiologist (the forward march of progress)

A new system called Sedasys, made by Johnson & Johnson, JNJ -1.31% would automate the sedation of many patients undergoing colon-cancer screenings called colonoscopies. That could take anesthesiologists out of the room, eliminating a big source of income for the doctors. More than $1 billion is spent each year sedating patients undergoing otherwise painful colonoscopies, according to a RAND Corp. study that J&J sponsored.

J&J hopes the potential savings from using Sedasys will appeal to hospitals and clinics and drive machine sales, which are set to begin early next year. Sedasys “is a great way to improve care and reduce costs,” J&J CEO Alex Gorsky said in an interview.

Anesthesiologists’ services usually cost more than the $200 to $400 generally charged by physicians performing the actual colon-cancer screenings, says health-plan CDPHP in New York state. An anesthesiologist’s involvement typically adds $600 to $2,000 to the procedure’s cost, according to a research letter published online by JAMA Internal Medicine in July.

By contrast, Sedasys would cost about $150 a procedure, according to people familiar with J&J’s pricing plans. Hospitals and clinics won’t buy the machines, instead paying a fee each time they use the device, these people say. The $150 would cover maintenance and all the costs of performing the procedure except the sedating drug used, which would add a few dollars, one of the people says.

Here is more. As you might expect, anesthesiologists are convinced this is a bad idea.

Behavioral biases in charitable giving, installment #1637

People pay more attention to the number of people killed in a natural disaster than to the number of survivors when deciding how much money to donate to disaster relief efforts, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

…Their model estimated that about $9,300 was donated per person killed in a given disaster. The number of people affected in the disasters, on the other hand, appeared to have no influence on the amount donated to relief efforts.

The summary article is here, and the gated published version is here. I do not see an ungated copy. Here is a related paper (pdf) on how disasters drive aid decisions.

For the pointer I thank Bill Benzon.

Colin Camerer wins a MacArthur Genius grant

The notice is here. Camerer is an economist at CalTech, a founding pioneer of neuroeconomics, and a former child prodigy, the standard set of links on him is here. You can follow Colin on Twitter here.

And don’t neglect these three winners (among others):

— Jeremy Denk, 43, New York City. Writer and concert pianist who combines his skills to help readers and listeners to better appreciate classical music.

— Angela Duckworth, 43, Philadelphia. Research psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania helping to transform understanding of just what roles self-control and grit play in educational achievement. [TC: Duckworth’s home page is here and her research focuses on conscientiousness as a major factor behind educational success]

— Vijay Iyer, 41, New York City. Jazz pianist, composer and bandleader and writer reconceptualizing the genre through compositions for his ensembles, as well as cross-disciplinary collaborations and scholarly writing.

New markers of political and managerial hubris

Gillian Tett reports:

The number of “linguistic biomarkers” associated with hubris was highest for Mr Blair, followed by Thatcher – with Mr Major a long way behind. Hubris increased both in the speeches of Mr Blair and of Thatcher – with a particularly marked rise after periods of war (in the former case, this was the conflict in Iraq; for the latter, the Falklands war.) Mr Blair started using words such as “I”, “me” and “sure” more.

…Niamh Brennan and John Conroy, a professor and a graduate student, analysed the letters to shareholders issued by the chief executive of a European bank that expanded very dramatically during the boom and then suffered massive losses. Their analysis showed that during the eight years that he was in power, this chief executive also displayed rising hubris in his speech, with excessive optimism and a growing use of the royal “we”.

“From a total of 148 sentences identified as being good news, 57 per cent was attributed to the chief executive himself, while only 39 per cent was attributed to the company and a further 4 per cent to outside parties,” they write. But the chief executive “did not attribute any bad news to themselves or the company but stated it was the result of external factors.”

This research program is in its early stages.

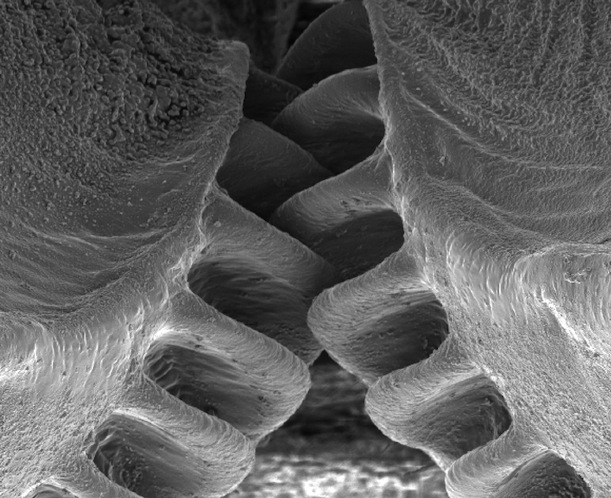

Insect Gear

The only functional gears ever found in nature belong to a small insect. The gears lock the insect’s back legs together giving it a synchronized and powerful jump. The electron microscope picture of the gears is stunning:

The original paper is here and you can find a summary with more pictures of the gear in action here.

The case of the disappearing teaspoons

That is the title of a new research paper, by Lim, Hellard,and Aitken, and here are some of the key results:

Subjects 70 discreetly numbered teaspoons placed in tearooms around the institute and observed weekly over five months.

Main outcome measures Incidence of teaspoon loss per 100 teaspoon years and teaspoon half life.

Results 56 (80%) of the 70 teaspoons disappeared during the study. The half life of the teaspoons was 81 days. The half life of teaspoons in communal tearooms (42 days) was significantly shorter than for those in rooms associated with particular research groups (77 days). The rate of loss was not influenced by the teaspoons’ value. The incidence of teaspoon loss over the period of observation was 360.62 per 100 teaspoon years. At this rate, an estimated 250 teaspoons would need to be purchased annually to maintain a practical institute-wide population of 70 teaspoons.

For the pointer I thank Tord Mule, guitar shredder.