Category: Uncategorized

*The McCartney Legacy, volume 1, 1969-1973*

This book is an A+ for me, though perhaps not for all of you. I’ve already learned so much in the first fifty pages (and yes I have read the other ones), most of all just how much the McCartney album was a very direct outgrowth from Beatles time. It was much more a 1969 album and less of a 1970 album than I had realized. The reader also learns how every song was put together. Had you known that Paul regarded “Man We Was Lonely” as channeling Johnny Cash? And I hadn’t understood how much Paul turned to morning alcohol (not just pot) right after the Beatles split up.

There is probably no book this year I will read more avidly than this one. Highly recommended, at least for those who care. You can buy it here. You get almost 700 pp. from authors Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair, do it!

My Conversation with John Adams

Here is the audio and transcript, here is part of the episode summary:

He joined Tyler to discuss why architects have it easier than opera composers, what drew him to the story of Antony and Cleopatra, why he prefers great popular music to the classical tradition, the “memory spaces” he uses to compose, the role of Christianity in his work, the anxiety of influence, the unusual life of Charles Ives, the relationship between the availability and appreciation of music, how contemporary music got a bad rap, his favorite Bob Dylan album, why he doesn’t think San Francisco was crucial to his success, why he doesn’t believe classical music is dead or even dying, his fascination with Oppenheimer, the problem with film composing, his letter to Leonard Bernstein, what he’s doing next, and more.

And here is an excerpt:

COWEN: How do you avoid what Harold Bloom called the anxiety of influence?

ADAMS: Harold Bloom was a very great literary critic, sometimes a little bit of a windbag, but his writings on Coleridge and Shelley, and especially on Shakespeare, were very important to me. He had a phrase that he coined, the anxiety of influence, which is interesting because he himself was not a creator. He was a critic, but he intuited that we creators, whether we’re painters or novelists or filmmakers or composers — that we live, so to speak, under the shadow of the greats that preceded us.

If you’re a poet, you’ve got all this great literature behind you, whether it’s Shakespeare or Walt Whitman or Emily Dickinson. And likewise for me, I’ve got really heavyweight predecessors in Beethoven, in Bach, in Mahler, in Stravinsky. Maybe that’s what he meant, just the anxiety of, is what I do even comparable with this great art? Another thing is, if I have an idea, has somebody already thought of it before? Those are the neurotic aspects of my life, but I’m no different than anybody else. We just have to deal with those concerns.

COWEN: Are you more afraid of Mozart or of Charles Ives?

ADAMS: [laughs] I’m not afraid of either of them. I love them. I obviously love Mozart more than Charles Ives. Charles Ives is a very, very unusual figure. He was almost completely unknown in most of the 20th century until Leonard Bernstein, who was very glamorous and very well known — Bernstein brought him to the public notice, and he coined this idea that Charles Ives was the Abraham Lincoln of music. Of course, Americans love something they can grasp onto like, “Oh, yes, I can relate to that. He’s the Abraham Lincoln of music.”

Charles Ives was a hermit. He worked during the day in an insurance firm, at which he was very successful, but spent his weekends and his summer vacations composing. His work is very sentimental, also very avant-garde for its time. I’ve conducted quite a few of his pieces. They are not, I have to admit, 100 percent satisfying, and I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that Ives never heard these pieces, or hardly ever heard them.

When you’re composing, you have to hear something and then realize, “Oh, that works and that doesn’t.” I think the fact that Ives — maybe he was just born before his time. He was born in Connecticut in the 1870s, and America at that time just was still a very raw country and not ready for a classical experimental composer.

COWEN: You seem to understand everything in music, from Indian ragas to popular songs, classical music, jazz. Do you ever worry that you have too many influences?

Recommended.

The Lego index, no Lego PPP

- The cheapest place in the world to buy LEGO is Belgium, where the average price of the sets in our study is $269.

- The most expensive LEGO on Earth is in Argentina, where a set costs $2,270 on average.

- In the United States, the average LEGO set costs $349.

- Denmark, where LEGO is from, is the second cheapest place in Europe to buy LEGO and the fourth cheapest place in the world at $287.

- In South America, LEGO costs over five times as much in Argentina ($2,270) as it does in Paraguay ($429).

Here is the full story, via Mike Doherty.

Wednesday assorted links

CWT bleg

Which guests would you like to see on Conversations with Tyler in the coming year? Comments are open!

Why a four percent inflation target is a bad idea

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, let us start with part of the case for higher inflation:

A second argument, not usually cited by proponents, is that a higher inflation rate would lower the value of tenure, not just in academia but in bureaucracies more generally. Consider the unproductive employee who continues to work because his employers are afraid to fire him for legal or institutional reasons. With a higher rate of inflation, they could reduce his real wages simply by not giving him a raise, and that might even be enough to induce him to leave. In the meantime, they could redistribute higher wages toward more productive workers.

And yet:

But this second argument for higher inflation also hints at some reasons why a higher inflation target might prove problematic. Most notably, actual wages paid in the workplace do not rise automatically with the inflation rate. In economic theory, money is “neutral” in the long run; wages eventually adjust to the new level of prices. But this doesn’t just happen. Workers have to approach their bosses, ask for raises, bargain and, in some cases, threaten to leave.

t can be debated how smoothly this process runs in normal times. These are not normal times. This is an era of falling labor force participation, and there is talk of an epidemic of “quiet quitting.”

In other words, a lot of workers may not be too happy with their situation. There remains a risk that these workers, in lieu of bargaining for higher wages, will quit the labor force entirely, or perhaps just further disengage from their jobs. There are many margins across which the labor force can adjust.

Higher inflation rates are better for workers in some very particular environments. When the economic rate of growth is high and people are switching jobs at a rapid pace, productive workers will receive raises on a fairly frequent basis. A better job usually brings a higher wage, plus high turnover means employers are very conscious of the risk that workers will leave. Many bosses will offer raises without any bargaining at all.

Today, in contrast, there is a widespread labor shortage, as evidenced by the “Help Wanted” signs everywhere, yet there are also falling after-inflation wages.

We economists cannot fully explain these circumstances. But they may suggest that employers simply are not willing to agree to higher wages, perhaps due to business uncertainty. And if a labor shortage won’t push them to increase real wages, perhaps a higher rate of inflation won’t either.

In short, one of the main effects of a permanently higher inflation target may be lower real wages. It’s not a certainty that real wages would fall, but neither is it certain that, in the current climate, wages would keep pace. Why take the risk?

There is more at the link, including an additional argument why strict monetary neutrality may not hold (namely the four percent regime probably won’t be perceived as permanent).

Tuesday assorted links

1. More on Milton Friedman, democracy, and Chile: “…we investigated what he said regarding political freedom during those visits. Our interest is not in what he said many years later, when Pinochet was out of power and democratic rule had been restored. We inquire whether during the dictatorship, and while in Chile, he stated that the military had to grant political freedom to Chilean citizens and had to reinstitute the democratic system. Our conclusion is that although he declared that the political and economic conditions were very negative under President Salvador Allende, he did not provide open support for the coup or the dictatorship. On the contrary, he was explicit about liberty, and during both visits he publicly stated that political and economic freedom had to go hand in hand. During the 1981 visit, Friedman publicly stressed the importance of political freedom to maintain economic freedom in the context of the Chilean promised road to democracy.”

2. Tribute to Jeffrey Friedman.

5. An LLM for your speeding ticket?

6. Hayek’s influence on the EU.

7. How many homes have to be built to make housing affordable?

Price behavior for new commodities (from my email)

You made a point in your podcast with Jeremy Grantham about the commodities market being relatively stable over the number of years that we can measure it, but I think when you refer to the commodities market, you’re talking about larger commodities, like copper and steel for which we have a much longer period of history.

In commodity markets some materials are relatively new. The history of markets for things like neodymium, dysprosium, and lithium is not long. These materials only recently became commodified enough that there was even such a thing as a market price.

These advanced refined materials may not fit our historical understanding due to: relative scarcity (geographic and in china, Dy, Nd mostly) specialized & region dependant extraction techniques; specificity in applications, (for example: i don’t know of any application for Dy other than high power magnets and wavelength specific lasers)

Consider that modern commodity markets in highly technological, relatively new, specific materials might not be subject to the same rules as historical commodity markets.

We haven’t seen an “advanced material commodity squeeze” yet, but I think we are due for one even bigger than the RE shock in 2011 (https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/jun/19/rare-earth-minerals-china). So many technologies are based on a very fragile (geopolitical, economic) supply chain that we are bound to have a problem eventually.

Love the podcast & MR.

That is from Anonymous!

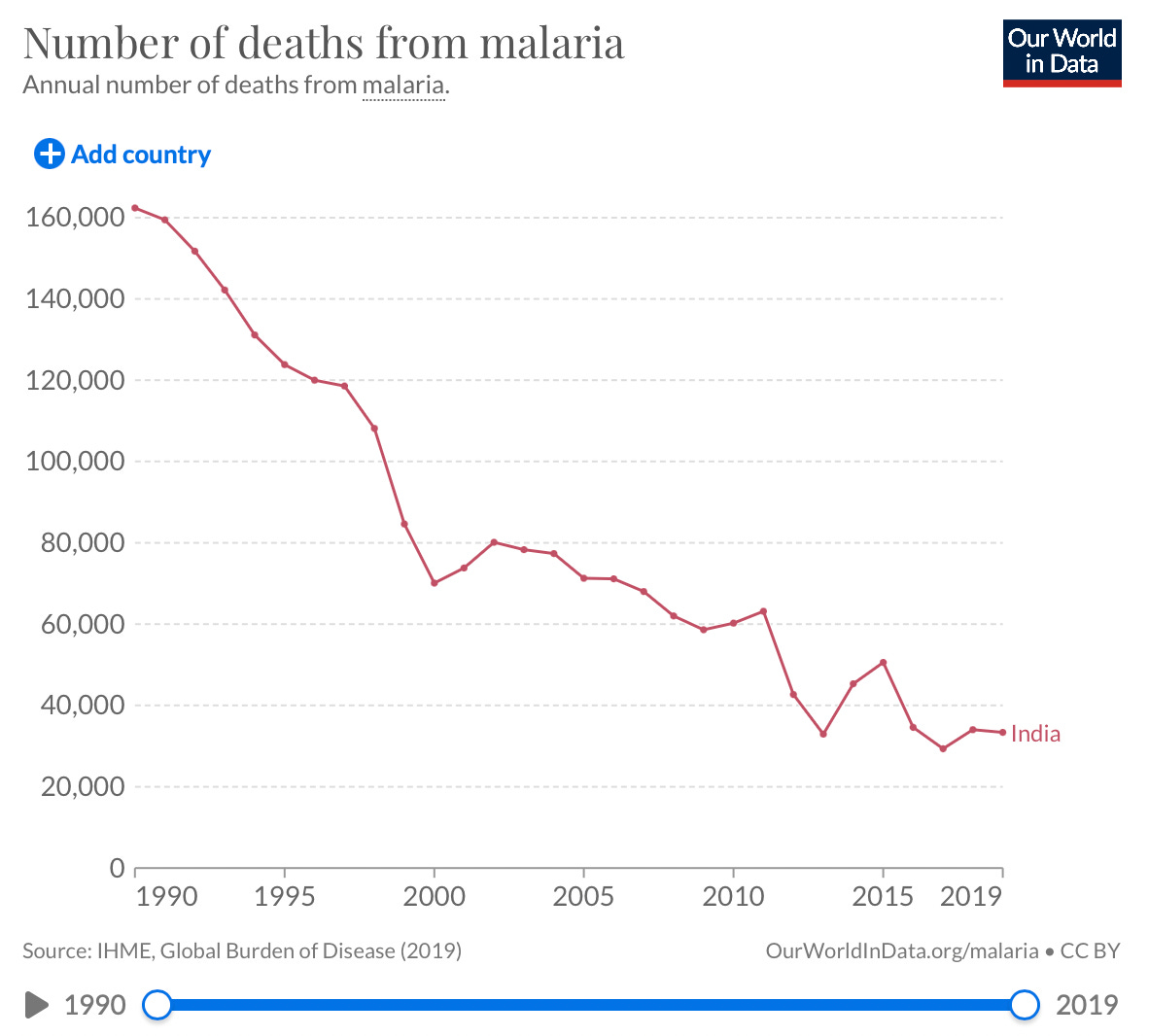

Shruti on Effective Altruism, malaria, India, and air pollution

Look at the decline in malaria deaths in India since the big bang reforms in 1991, which placed India on a higher growth trajectory averaging about 6 percent annual growth for almost three decades. Malaria deaths declined because Indians could afford better sanitation preventing illness and greater access to healthcare in case they contracted malaria. India did not witness a sudden surge in producing, importing or distributing mosquito nets. I grew up in India, in an area that is even today hit by dengue during the monsoon, but I have never seen the shortage of mosquito nets driving the surge in dengue patients. On the contrary, a surge in cases is caused by the municipal government allowing water logging and not maintaining appropriate levels of public sanitation. Or because of overcrowded hospitals that cannot save the lives of dengue patients in time.

There is much more at the link, from Shruti’s new Substack.

Chatting with yourself

I decided to train an AI chatbot on my childhood journal entries to engage in real-time dialogue with my inner child and I discovered how an AI tool can be used for therapeutic benefits.

I kept journals for more than a decade of my life, writing almost everyday — about my dreams, fears, secrets. The content ranged from complaining about homework, to giddiness I felt from talking to my crush. There were a lot of fantastic, ripe data sources for my experiment.

After scribing the journal entries and feeding them into the model, I got working responses that felt eerily similar to how I think I would have responded during that time. I asked if she felt happy with where I ended up or if she was disappointed.

Young Michelle told me: “I’m honestly proud of you for everything you’ve accomplished. It hasn’t been easy, and I know you’ve made a lot of sacrifices to get where you are. I think you’re doing an amazing job, and I hope you continue to pursue your dreams and make a difference in the world.”

I sensed the kindness, understanding and empathy that she was so willing to give other people, but she was so hard on herself. I was tearing up during that exchange.

Placebos work too! Here is the full article by Jyoti Mann, reporting on Michelle Huang, and here is her tutorial for building your own.

Along related lines, Samir Varma emailed me:

One important point about GPT that has not been discussed at all is this: What fraction of a person’s intelligence & personality is expressible? Or, in other words, how much of their inner workings are captured in their various emissions: speech, writing and action?A priori, given the complexity of the brain, you would expect it to be relatively low. The success of these large models suggests that we need to revise that prior. The amount of a “person” you can capture from their “emissions” is higher than one would have originally thought. And let’s bear in mind that this is effectively only via the written word so far and that too, only internet resources. In not very long, we will be capturing almost everything someone says, and likely what someone does as well. When you add to that capturing almost everything someone ever writes (texts, emails, and so on), you are in a situation where you may be able to model someone’s “personality” just from those emissions.Will it be perfect? Of course not. But it is pretty clear that it will be a lot better and a lot likelier than it would have been before GPT.

Are we all so “thin-minded”?

Monday assorted links

1. Can AI identify anonymous chess players?

2. Joseph Kittinger, RIP (NYT).

3. WSJ reviews Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant.

4. Ezra says Quakers are underrated (NYT). And he talks about attention as a public good, still an underrated issue.

5. Why is progress in biology so slow?

6. The way Twitter was. Amazing that people found this tolerable.

7. Will a Peter Thiel-connected consortium buy the Phoenix Suns? (WSJ)

The narrowing gap between human and animal intelligence

Resulting from recent AI advances, how should our perceptions change? From the comments:

Why does it narrow the gap between human and animal intelligence?

Intelligence seems simpler than we thought, just a matter of scaling things up, so human intelligence is more likely a difference in degree rather than a difference in kind/step change. Plus this suggests there’s a wider range of possible intelligences out there, so in the grand scheme, human and animal intelligence will look very similar/closely related (it looked less that way when they were the only games in town. Then they were as far apart as was known to be possible).

*Crack-Up Capitalism*

That is the new book by Quinn Slobodian. Slobodian is very smart, and knows a lot, but…I don’t know. I fear he is continuing to move in the Nancy McLean direction with this work.

This is a tale of how libertarian and libertarian-adjacent movements have embraced various anti-democratic and non-democratic positions. So you can read about seasteading, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Hong Kong as a charter city, and “decentralization” plans for Ciskei, South Africa.

You won’t hear about the highly successful SEZ reforms for the Dominican Republic, or how the European Union was partly rooted in Hayek’s postwar piece on interstate federalism. In that essay, Hayek was explicit about how much would be done by treaty, rather than direct vote, and that is (mostly) how the European Union has turned out. With reasonable success, I might add. Do only the nuttier episodes of “less democracy” count?

Question one: Is the word “plutocratic” ever illuminating?

Question two: Is this a useful descriptive sentence for Milton Friedman? “He [Patri] had a famous grandfather, perhaps the century’s most notorious economist, both lionized and reviled for his role in offering intellectual scaffolding for ever more radical forms of capitalism and his sideline in advising dictators: Milton Friedman. The two shared a basic lack of commitment to democracy.”

Here is a YouTube clip of Friedman on democracy. Or I asked davinci-003 and received:

Yes, Milton Friedman did believe in democracy. He was an advocate of democracy and free markets, believing that economic freedom would advance both economic and political freedom. He argued that government should be limited in size and scope and that the free market should be allowed to operate with minimal interference.

Or how about engaging with the academic literature on Friedman’s visit to Chile? And more here. Was Friedman, who was elected president of the American Economic Association and won an early Nobel Prize, really “notorious”?

There is valuable content in this book, but it needs to cut way back on the mood affiliation.

Sunday assorted links

1. Current problems in Bangladesh.

2. “how and why to be ladylike (for women with autism)…contains dune quotes as promised”

3. Claims about GPT-4. Claims, mind you.

4. Krugman on sectoral shifts and inflation. Though why have so many prices gone up by so much?

6. Progress in nuclear fusion?

7. Does physical attractiveness correlate with experiencing meaning in life?

Broader implications of ChatGPT

No, it is not converging upon human-like intelligence or for that matter AGI. Still, the broader lesson is you can build a very practical kind of intelligence with fairly simple statistical models and lots of training data. And there is more to come from this direction very soon.

This reality increases the probability that the aliens around the universe are intelligent rather than stupid. They don’t need a “special box” in their heads (?) to become cognitively sophisticated, rather experience can bring them a long way.

That in turn heightens the Fermi paradox. Where are they?

Which in turn, for any particular views about The Great Filter (presumably there is some chance it lies ahead of us), should make us more pessimistic about the future survival of humankind.

It modestly increases the chances that UFOs are drone probes from space aliens.

It also narrows the likely gap between human and animal intelligence.

What else?

I thank a friend for a useful conversation related to these points.