The home bias in sovereign ratings

There is a new and intriguing paper on this topic, by Andreas Fuchs and Kai Gehring, the abstract is this:

Credit rating agencies are frequently criticized for producing sovereign ratings that do not accurately reflect the economic and political fundamentals of rated countries. This article discusses how the home country of rating agencies could affect rating decisions as a result of political economy influences and culture. Using data from nine agencies based in six countries, we investigate empirically if there is systematic evidence for a home bias in sovereign ratings. Specifically, we use dyadic panel data to test whether, all else being equal, agencies assign better ratings to their home countries, as well as to countries economically, politically and culturally aligned with them.

While most of the variation in ratings is explained by the fundamentals of rated countries, our results provide empirical support for the existence of a home bias in sovereign ratings. We find that the bias becomes more accentuated following the onset of the Global Financial Crisis and appears to be driven by economic and cultural ties, not geopolitics.

The paper has been covered by FT Alphaville, by China Daily, and by Der Spiegel (in German).

Neumark and Wascher on minimum wages and youth unemployment

Here is the abstract from their piece from 2003 (pdf):

We estimate the employment effects of changes in national minimum wages using a pooled cross-section time-series data set comprising 17 OECD countries for the period 1975-2000, focusing on the impact of cross-country differences in minimum wage systems and in other labor market institutions and policies that may either offset or amplify the effects of minimum wages. The average minimum wage effects we estimate using this sample are consistent with the view that minimum wages cause employment losses among youths. However, the evidence also suggests that the employment effects of minimum wages vary considerably across countries. In particular, disemployment effects of minimum wages appear to be smaller in countries that have subminimum wage provisions for youths. Regarding other labor market policies and institutions, we find that more restrictive labor standards and higher union coverage strengthen the disemployment effects of minimum wages, while employment protection laws and active labor market policies designed to bring unemployed individuals into the work force help to offset these effects. Overall, the disemployment effects of minimum wages are strongest in the countries with the least regulated labor markets.

Argentina tries to stave off a continuing financial crisis

Argentina has introduced new restrictions on online shopping as part of efforts to stop foreign currency reserves from falling any further.

…Items imported through websites such as Amazon and eBay are no longer delivered to people’s home addresses. The parcels need to be collected from the customs office.

Believe it or not, there is several hours wait at the customs office. There is more here, via Counterparties.

Assorted links

1. Explaining how the Mini-Med plans are possible under ACA.

2 The absence of net neutrality in some developing economies.

3. Rizwan Muazzam Qawwali (video, intense).

4. Volokh Conspiracy will join The Washington Post. And a few articles on Ezra Klein and all that stuff, here and here and here and Krugman here.

5. What is on the horizon for ACA? Read especially the second part of the post on potential crises to come.

6. Dube on the minimum wage and poverty.

7. Good update on North Carolina and unemployment insurance, good graphs too.

How Many Homicides were there in 2010?

How many homicides were there in 2010 in the United States? Well, that’s easy. Let’s just do some Googling:

Between the smallest and largest figures there is a difference of 3,292 deaths or 25%!

The differences are striking but not entirely arbitrary or without explanation. I assume the second figure adds late additions to the 2010 data and so should be considered more authoritative but that is a relatively small difference.

The difference between 2 and 3 is puzzling and seems to be that the number in 2 is drawn from the Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) statistics on victims while the larger figure is drawn from homicide reports in the UCR. Not all agencies collect the more detailed statistics in the SHR while the UCR is nearly complete. Thus the victim figure is smaller than the report figure (this doesn’t appear to conform exactly to where the data is supposed to be sourced but it’s what the FBI tells me). It’s unclear why the FBI would report both figures when they know one is misleading.

The difference between 3 and 4 comes from different definitions of homicide. The FBI collects data on crimes. If a killing is ruled justified, i.e. not a crime, it doesn’t go into the FBI homicide statistics. The CDC collects data from death certificates which list as homicide any death caused by “injuries inflicted by another person with intent to injure or kill, by any means.” Thus, the CDC data includes justifiable homicide. In 2010 according to the FBI there were 387 justifiable homicides by law enforcement and 278 by private citizen for a total of 665 justifiable homicides, so that accounts for some but not all of the difference.

(By the way, the 278 justifiable homicides in 2010 by private citizens compared to 387 by law enforcement and 14,720 unjustifiable homicides would seem to be an important context for many claims about stand your ground laws. N.b. this doesn’t mean that the laws couldn’t be associated with more unjustifiable homicides).

The FBI (3) and NVSS (4) figures track each other closely over time but its important to be aware of the differences and to be consistent in one’s calculations.

Which kinds of music are encouraged by streaming vs. downloads?

Let’s compare iTunes downloads to a mythical perfect streaming service which lets you listen to everything for a fixed fee each month or sometimes even for free. In the interests of analytical clarity, I will oversimplify some of the actual pricing schemes associated with streaming and consider them in their purest form.

Streaming seems to encourage the demand for variety, so the website vendor wants to make browsing seem really fun, perhaps more fun than the songs themselves. (An alternative view is that the information produced by streaming services, and the recommendations, allow for in-depth exploration of genres and that outweighs the “greater ease of sampling of variety” effect. Perhaps both effects can be true for varying groups of listeners with somehow the “middle level of variety-seeking left in the lurch, relatively speaking.)

The music creators are incentivized to create music which sounds very good on first approach. Otherwise the listener just moves on to further browsing and doesn’t think about going to your concert or buying your album.

Streaming, with its extremely large menu, also means commonly consumed pieces will tend to be shorter or more easily broken into excerpts. This will favor pop music and I think also opera, because of its arias.

Advertising is a more important revenue source for streaming than it is for downloads. The music promoted by streaming services thus should contribute to the overall ambience and coolness of the site, and musicians who can meet that demand will find that their work is given more upfront attention. It encourages music whose description evokes a response of “Oh, I’ve never had that before, I’d like to try it.” Even if you don’t really care about it.

People who purchase advertised products are, on average, older than the people who purchase music. Streaming services thus should slant product and product accessibility on the site toward the musical tastes of older people.

Since streaming divides up revenues among a greater number of artists, that should encourage solo performers with low capital costs, who can keep their (tiny) share all for themselves. It also may require that the artists on streaming services can make a living or partial living giving concerts, even more so than under the previous world order.

This music industry source suggests that streaming boosts album sales in a way that downloads do not. It also questions whether that boost will be long-lived, as streaming services take over more of the market.

When the marginal cost of more music is truly zero, does that make musical choices more or less socially influenced?

Hannah Karp shows that in the new world of streaming, mainstream radio stations are responding by playing the biggest hits over and over again. Ad-supported media require the familiar song to grab and keep the attention of the listener. Risk-aversion is increasing, which probably pushes some marginal listeners, who are interested in at least some degree of exploration, into further reliance on streaming.

The top 10 songs last year were played close to twice as much on the radio than they were 10 years ago, according to Mediabase, a division of Clear Channel Communications Inc. that tracks radio spins for all broadcasters. The most-played song last year, Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines,” aired 749,633 times in the 180 markets monitored by Mediabase. That is 2,053 times a day on average. The top song in 2003, “When I’m Gone” by 3 Doors Down, was played 442,160 times that year.

So the differing parts of the market are interdependent here.

What do you think?

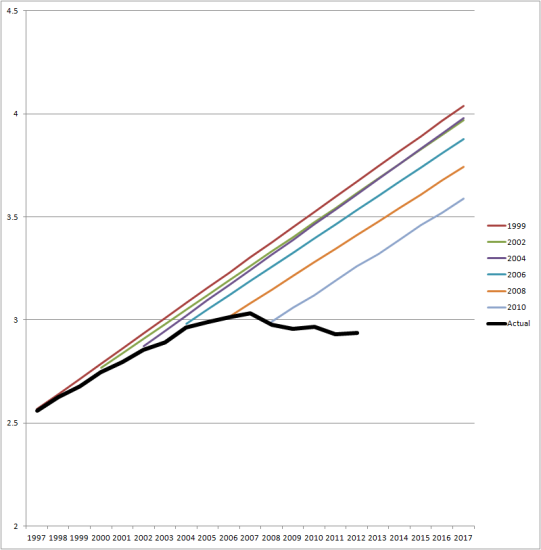

Traffic Forecasts

Official DOT forecasts of road traffic with actual road traffic.

Hat tip to Andrew Gelman, who compares it with some other famous forecasts.

Good Marc Andreessen piece on the broader implications of Bitcoin

Marc writes:

Think about content monetization, for example. One reason media businesses such as newspapers struggle to charge for content is because they need to charge either all (pay the entire subscription fee for all the content) or nothing (which then results in all those terrible banner ads everywhere on the web). All of a sudden, with Bitcoin, there is an economically viable way to charge arbitrarily small amounts of money per article, or per section, or per hour, or per video play, or per archive access, or per news alert.

Another potential use of Bitcoin micropayments is to fight spam. Future email systems and social networks could refuse to accept incoming messages unless they were accompanied with tiny amounts of Bitcoin – tiny enough to not matter to the sender, but large enough to deter spammers, who today can send uncounted billions of spam messages for free with impunity.

Finally, a fourth interesting use case is public payments. This idea first came to my attention in a news article a few months ago. A random spectator at a televised sports event held up a placard with a QR code and the text “Send me Bitcoin!” He received $25,000 in Bitcoin in the first 24 hours, all from people he had never met. This was the first time in history that you could see someone holding up a sign, in person or on TV or in a photo, and then send them money with two clicks on your smartphone: take the photo of the QR code on the sign, and click to send the money.

There is more here, interesting throughout.

Robert J. Barro on aggregate demand

There has been a recent kerfluffle over whether Robert Barro rejects the notion of aggregate demand, which he had written with quotation marks as “aggregate demand.” Scott Sumner surveys the back and forth.

I say use The Google to find out what Barro really thinks and indeed he has written a whole piece on the topic (jstor), namely “The Aggregate-Supply/Aggregate Demand Model,” from the mid 1990s, and here is the abstract:

In recent years, many macroeconomic textbooks at the principles and intermediate levels have adopted the aggregate-supply/aggregate-demand (AS-AD) frame- work [Baumol and Blinder, 1988, Ch. 11; Gordon, 1987, Ch. 6; Lipsey, Steiner, and Purvis, 1984, Ch. 30; Mankiw, 1992, Ch. 11]. The objective was to allow for supply shocks in a Keynesian framework and to generate more satisfactory predictions about the behavior of the price level. The main point of this paper is that the AS-AD model is unsatisfactory and should be abandoned as a teaching tool.

In one version of the aggregate-supply curve, the components of the AS-AD model as usually used are contradictory. An interpretation of the model to eliminate the logical inconsistencies makes it a special case of rational-expectations macro models. In this mode, the model has no Keynesian characteristics and delivers the policy prescriptions that are familiar from the rational-expectations literature.

An alternative version of the aggregate-supply curve leads to what used to be called the complete Keynesian model: the goods market clears but the labor market has chronic excess supply. This model was rejected long ago for good reasons and should not be resurrected now.

If you read the paper, you will see three things. First, Barro is fully aware of “AD-like” phenomena and does not reject that notion. Second, Barro seems to prefer the IS-LM model to AS-AD, albeit with some caveats about possible false predictions of IS-LM and also noting in footnote two that he prefers his own presentation in his 1993 text. Third, Barro’s criticism is (whether you agree or not) that AD-AS collapses too readily into standard rational expectations models and doesn’t really provide an independent foundation for sticky price macroeconomics. In a nutshell “The AS-AD model is logically flawed as usually presented because its assumption that the price level clears the goods market is inconsistent with the Keynesian underpinnings for the aggregate-demand curve.”

Krugman had written this:

If you read Barro’s piece, what you see is a blithe dismissal of the whole notion that economies can ever suffer from am inadequate level of “aggregate demand” — the scare quotes are his, not mine, meant to suggest that this is a silly, bizarre notion, in conflict with “regular economics.”

I believe that is not a good characterization of Barro’s views and it is also an object lesson in the importance of the Ideological Turing Test. I would cite not only this piece, but also forty years of journal articles, many of which study the importance of nominal shocks and demand, albeit without (in general) using textbook AD-AS terminology. Indeed, Barro working with Herschel Grossman is one of the founding fathers of quantity-constrained Keynesian sticky-price macro and he is still citing this work favorably in his mid-1990s piece; see for instance Barro and Grossman (1971, 1974) and also their book from 1976: “This is a textbook on macroeconomic theory that attempts to rework the theory of macroeconomic relations through a re-examination of their microeconomic foundations. In the tradition of Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money…”

On the UI issue, I would note that the multiplier from transfers is likely unimpressive relative to the multiplier from government consumption.

Harford Strikes Back

Tim Harford is speaking about his new book, The Undercover Economist Strikes Back, at Cato at noon on Thursday Jan. 23. I will be commenting. More info and to register here.

If you can’t make it to the Cato Institute, you can watch this event live online at www.cato.org/live.

Here is Cato’s announcement.

In his new book, Tim Harford attempts to demystify macroeconomics in the same way his earlier bestseller, The Undercover Economist, demystified microeconomics. Using his characteristic conversational style, Harford will discuss abstract macroeconomic ideas, explaining the most common models of recessions and the difficulty of discriminating between them on empirical grounds. For example, was the crisis of 2008 driven by supply- or demand-side factors? And why do failures of the financial sector seem to have such severe economic consequences? He will not shy away from other topics, including income inequality, or the growing interest in alternative measures of economic well-being, such as self-reported happiness. Please join us for a discussion of what macroeconomists believe about the economy and of why those beliefs often seem to lead to bad public policy.

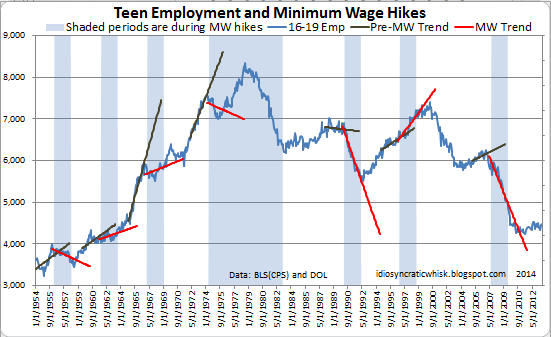

Teen employment and the minimum wage: sixty years of experience

Kevin Erdmann relates:

There is much more here. Kevin concludes: “Is there any other issue where the data conforms so strongly to basic economic intuition, and yet is widely written off as a coincidence?”

Where are the missing gains from trade?

There is a new and probably important paper by Marc J. Melitz and Stephen J. Redding on this topic. For this piece I find a segment in the middle to be more illuminating than the abstract:

Trade has a fractal-like property in this model, in which there are gains from trade at each intermediate stage of production. If one falsely assumes a single stage of production, when production is in fact sequential, these gains from trade at each intermediate stage show up as an endogenous increase in measured domestic productivity. As the number of production stages converges towards infinity, the welfare gains from trade become arbitrarily large. This captures the idea that trade involves myriad changes in the organization of production throughout the economy and the welfare costs from forgoing this pervasive specialization can be large.

As the domestic trade share for an individual production stage becomes arbitrarily small, the welfare gains from trade also becomes arbitrarily large. This captures the idea that some countries may have strong comparative advantages in some stages of production and the welfare losses from forgoing this specialization can be large.

Here is an ungated version of the paper. I would note this idea holds out the hope of integrating the technology diffusion literature with the more traditional international trade theory approaches.

Will Wilkinson, we miss ye

Here is part of Will’s new post:

…the fact is, mundane liberalism is flatly incompatible with the security state, as we know it. That anyone spurred to action against the illiberal security state by the democratic jusificatory ethos of mundane liberalism has come to seem a little “libertarian,” and may even therefore confess some personal “libertarian” sympathies, suggests to me a problem with “liberalism” as it is embodied in actual political discourse and practice. It suggests that liberalism is effectively a corrupt form of statist institutional conservatism, and that the democratic justificatory ethos of mundane liberalism has somehow survived within the ethos of “libertarianism,” even if, as an explicit doctrinal matter, libertarians are generally hostile to the ideas of democracy and the legitimate liberal state. It’s nice that libertarians have kept liberalism alive, but it would be even nicer if it were possible for liberals to espouse liberalism without therefore being confused for libertarians.

We all hope for more.

F.A. Hayek, *The Market and Other Orders*

That is the new University of Chicago Press volume of Hayek’s collected works, this time volume 15. It is the best single-volume introduction to Hayek’s thought, if you are going to buy or read only one. It has the best of the early essays, as you might find in Individualism and Economic Order, and then the best later essays which build upon those earlier insights.

Here is Bruce Caldwell’s introduction to the volume, for e-purchase. The book’s table of contents is here. Here is our MRU course on Friedrich Hayek.

Assorted links

1. Fun Twitter source of German words.

2. Not safe for work uses of Google Glass.

3. “Cataluña tiene un superávit de 4.000 millones.”

4. The true power of the Blockchain?

5. Update on The Orange County Register.

6. Too negative, too polemic, and too unreasonable, but if you wish to read an argument that Jane Austen was not in fact a game theorist, here goes.