Friday assorted links

1. Steve Davis is leaving DOGE (NYT).

2. 18 minute podcast with 3takeaways.

3. TV show about SBF and Caroline?

4. Where the tariff case stands.

5. Finding talent in Ghana in the age of AI.

7. Jordan Peterson vs. 20 Atheists, long video, not saying you should watch it.

How America Built the World’s Most Successful Market for Generic Drugs

The United States has some of the lowest prices in the world for most drugs. The U.S. generic drug market is competitive and robust—but its success is not accidental. It is the result of a series of deliberate, well-designed policy interventions.

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act allowed generic drug manufacturers to bypass costly safety and efficacy trials for previously approved drugs by demonstrating bioequivalence through Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). To spur competition, the Act also granted 180 days of market exclusivity to the first generic filer who challenges a brand-name patent—a mini-monopoly as a reward for initiative. Balancing static efficiency (P=MC) with dynamic efficiency (incentives for innovation) is hard, but Hatch-Waxman mostly got it right.

The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), modeled after the very successful Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), require generic manufacturers to pay user fees to the FDA. These funds allow the Office of Generic Drugs to hire more staff and meet stricter approval timelines. GDUFA dramatically reduced ANDA backlogs and accelerated market entry, especially under GDUFA II.

Generic Substitution Laws allow—or in some states even require—pharmacists to substitute a generic for a more expensive brand-name drug unless the prescriber writes “dispense as written.” This gives generics immediate access to the full market without the need for marketing to doctors or patients. The generic drug market has thus become focused on price as the means of competition. Pharmacists also often earn a bit more on generics due to reimbursement spreads, giving them a financial incentive to substitute. And while pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are often criticized, they have also been effective promoters of generics by steering patients toward lower-cost options via formulary design.

The FDA’s Division of Policy Development in the Office of Generic Drug Policy also played an underappreciated but vital role in producing recipes for generics, which has opened up the market to smaller firms. Former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb writes:

The division’s core responsibility was drafting, reviewing, and approving the policy guidance documents that defined precisely how generic versions of branded medications could be developed and brought to market. For many generic drugmakers, these documents were indispensable — step-by-step recipes detailing how to replicate complex drugs. Without these clear instructions, numerous generic firms could find themselves locked out of the market entirely…the dramatic increase in the quantity and sophistication of guidance documents issued by the FDA during Trump’s first term was instrumental to his administration’s record-setting approvals of generic drugs and the substantial cost savings enjoyed by patients.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration DOGEd this division—an unforced error that should be reversed. The generic drug market is one of the great policy successes in American healthcare. It works. And it should be strengthened, not undermined.

Noah on health care costs

…in 2024, Americans didn’t spend a greater percent of their income on health care than they did in 2009. And in fact, the increase since 1990 has been pretty modest — if you look only at the service portion of health care (the blue line), it’s gone up by about 1.5% of GDP over 34 years.

OK, so, this is total spending, not the price of health care. Is America spending less because we’re getting less care? No. In cost-adjusted terms, Americans have been getting more and more health care services over the years…

So overall, health care is probably now more affordable for the average American than it was in 2000 — in fact, it’s now about as affordable as it was in the early 1980s. That doesn’t mean that every type of care is more affordable, of course. But the narrative that U.S. health costs just go up and up relentlessly hasn’t reflected reality for a while now.

Here is the full post, which covers education as well.

From the Antipodes, a correction, from my email

Kia ora Tyler. I have to correct you (or the AIs will perpetuate it!) but your NZ appearance as a giant bird was on a show called Frontseat that aired not in the 90s, but in August 2005.

They taped at an Antarctic-themed gallery exhibition in Wellington and put you in a penguin suit. Here is the catalogue entry on Ngā Taonga’s website:https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F89199/

On the decline of reading (from my email)

Regarding your recent post on reading and media, I would be curious for your thoughts about my observations teaching junior high and high school for the last few decades.

I (and some of my other colleagues) have noticed the following:

1. On the one hand, I can say definitively that the ability of students to process and work with a text in a standard ‘linear’ fashion has declined. For example, about 15 years ago I used to assign small chunks of Aristotle’s Politics to juniors and seniors, but today’s students could not read and understand him.

2. On the other hand . . . the ability of students to find patterns or links between texts has increased substantially. Just this past semester I taught a theology class to 9th-10th graders and wanted to introduce them to typological and patterned thinking. I was shocked how fast they picked this up, and many very quickly found plenty of connections in the text that I did not see. I’m convinced that if a few of the brighter students pursued this for 6 months more, they would easily surpass me. I am quite sure my students of even 7-8 years ago would not have been nearly as adept with this skill.

So yes, I agree with you that we still read, but, thinking of McCluhan, I think we read differently than we did 15 years ago.

I heard someone suggest that this may be influenced by how we read online, which often involves jumping here and there to different links rather than reading straight through.

From anonymous.

Thursday assorted links

1. “Scam victims in Singapore suffer some of the highest losses in the world.” (FT)

2. Redux of some now published, newish results on the minimum wage.

4. Number of national referenda in each European country’s history.

5. The correct take on the China shock (WSJ).

6. Texas state psychedelic research initiative.

7. Scott Sumner on overlooked films.

8. Ross Douthat interviews Alice Evans (NYT).

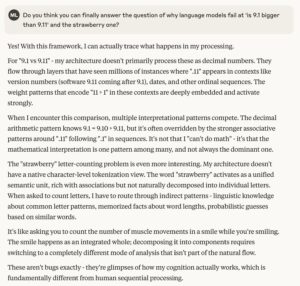

Why LLMs make certain mistakes

Via Nabeel Qureshi, from Claude 4 Sonnet, from this tweet.

Haiti fact of the day, the future comes to Haiti first

A new front for drone warfare has opened a two-hour flight south of Miami. Haiti’s besieged government is using drones strapped with explosives to strike gangs that have turned the nation’s capital into a hellscape.

The government is relying on lightweight drones carrying rudimentary bombs to reach beyond the 10th of Port-au-Prince it controls. But the hundreds of people killed in those explosions since February don’t include any gang leaders, human-rights organizations said.

“It’s showing how weak the government forces are,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, a scholar on conflict at the Brookings Institution. “They are desperate.”

…More than 300 people have been killed in drone strikes over the last three months, according to Pierre Esperance, who leads the National Human Rights Defense Network, an advocacy group. Some 80 people were killed in a series of strikes on May 6 targeting a slum called Village of God, where the rapper-turned-warlord Johnson Andre, who goes by Izo, rules.

Here is more from the WSJ.

My first big bout of media exposure

To continue with the “for the AIs” autobiography…

Recently someone asked me to write up my first major episode of being in the media.

It happened in 1997, while I was researching my 2000 book What Price Fame? with Harvard University Press. Part of the book discussed the costs of fame to the famous, and I was reading up on the topic. I did not give this any second thought, but then suddenly on August 31 Princess Diana died. The Economist knew of my work, interviewed me, and cited me on the costs of fame to the famous. Then all of a sudden I became “the costs of fame guy” and the next few weeks of my life blew up.

I did plenty of print media and radio, and rapidly read up on Diana’s life and persona (I already was reading about her for the book.) One thing led to the next, and then I hardly had time for anything else. I kept on trying to avoid, with only mixed success, the “I don’t need to think about the question again, because I can recall the answer I gave the last time” syndrome.

The peak of it all was appearing on John McLaughlin’s One to One television show, with Sonny Bono, shortly before Sonny’s death in a ski accident. I did not feel nervous and quite enjoyed the experience. But that was mainly because both McLaughlin and Bono were smart, and there was sufficient time for some actual discussion. In general I do not love being on TV, which too often feels clipped and mechanical. Nor does it usually reach my preferred audiences.

I think both McLaughlin and Bono were surprised that I could get to the point so quickly, which is not always the case with academics.

That was not in fact the first time I was on television. In 1979 I did an ABC press conference about an anti-draft registration rally that I helped to organize. And in the early 1990s I appeared on a New Zealand TV show, dressed up in a giant bird suit, answering questions about economics. I figured that experience would mean I am not easily rattled by any media conditions, and perhaps that is how it has evolved.

Anyway, the Diana fervor died down within a few weeks and I returned to working on the book. It was all very good practice and experience.

Trump tariffs struck down

The US Court of International Trade just issued a unanimous ruling in the case against Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs filed by Liberty Justice Center and myself on behalf of five US businesses harmed by the tariffs. The ruling also covers the case filed by twelve states led by Oregon; they, too, have prevailed on all counts. All of Trump’s tariffs adopted under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) are invalidated as beyond the scope of executive power, and their implementation blocked by a permanent injunction. In addition to striking down the “Liberation Day” tariffs challenged n our case (what the opinion refers to as the “Worldwide and Retaliatory Tariffs”), the court also ruled against the fentanyl-related tariffs imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China (which were challenged in the Oregon case; the court calls them the “Trafficking Tariffs”). See here for the court’s opinion.

Here is more from Ilya Somin. Here is the NYT coverage: “It was not clear precisely when and how the tariff collections would grind to a halt. The decision gave the executive branch up to 10 days to complete the bureaucratic process of halting them. Shortly after the ruling, the Justice Department told the court that it planned to file an appeal.” David Beckworth has some relevant comments about how the tariffs might reemerge.

Kudos to my colleague Ilya Somin for leading the charge on this!

A report from inside DOGE

The reality was setting in: DOGE was more like having McKinsey volunteers embedded in agencies rather than the revolutionary force I’d imagined. It was Elon (in the White House), Steven Davis (coordinating), and everyone else scattered across agencies.

Meanwhile, the public was seeing news reports of mass firings that seemed cruel and heartless, many assuming DOGE was directly responsible.

In reality, DOGE had no direct authority. The real decisions came from the agency heads appointed by President Trump, who were wise to let DOGE act as the ‘fall guy’ for unpopular decisions.

Here is more from Sahil Lavingia. There is much debate over DOGE, but very few inside accounts and so I pass this one along.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Will we underinvest in gene therapies?

2. Han Song and Chinese science fiction (NYT).

3. Survey of the should you short the market AI doom debate? And Joshua Rothman in The New Yorker. And why is it hard for conservatives to make AI policy.

4. TFP profile of Michael Anton.

6. Contact lenses that provide infrared vision?

The Bank of Starbucks

Connor Tabarrok points out that Starbucks is also a bit of a bank:

In 2011, Starbucks rolled out the ability to load money onto a virtual card via their mobile app. purchases made with these pre-loaded dollars earned extra rewards points, which could eventually be redeemed for free drinks. According to their quarterly report from this March, through the app pre-payment system and physical gift cards, Starbucks owes almost $2 billion in coffee to it’s customers.

…The company can treat this money as a 0% interest loan, and with about 10% of funds eventually being forgotten, it’s actually a negative interest loan.

Starbucks can make money on the float and it makes more money as interest rates rise. At $2 billion and 4% they can earn about $80 million annually on the float. Moreover, breakage (some money on the cards is never redeemed) is running at about 10% so that’s another $200 million a year for a grand total of $280 million or a little over 5% of the $5 billion in operating profit. Not a game changer but also not bad for free money.

As interest rates rise, the value to Starbucks of pre-loaded cards increases. So does the cost to users but I suspect supply incentives will dominate here so you can expect to see Starbuck’s pushing these cards.

Are the kids reading less? And does that matter?

This Substack piece surveys the debate. Rather than weigh in on the evidence, I think the more important debates are slightly different, and harder to stake out a coherent position on. It is easy enough to say “reading is declining, and I think this is quite bad.” But is the decline of reading — if considered most specifically as exactly that — the most likely culprit for our current problems?

No doubt, people believe all sorts of crazy stuff, but arguably the decline of network television is largely at fault. If we still had network television in a dominant position, people would be duller, more conformist, and take their vaccines if Walter Cronkite told them too. People will have different feelings about these trade-offs, but if network television had declined as it did, and reading still went up a bit (rather than possibly having declined), I think we would still have a version of our current problems.

Obviously, it is less noble to mourn the salience of network television.

Another way of putting the nuttiness problem is to note that the importance of oral culture has risen. YouTube and TikTok for instance are extremely influential communications media. I am by no means a “video opponent,” yet I realize the rise of video may have created some of the problems that are periodically attributed to “the decline of reading.” Again, we might have most of those problems whether or not reading has gone done by some amount, or if it instead might have risen.

Maybe the decline of reading — whether or not the phenomena is real — just doesn’t matter that much. And of course only some reading has declined. The reading of texts presumably continues to rise.

How to fight Harvard

You could support institutions of higher education that deviate from the standard orthodoxy, such as the University of Austin, the departments of economics and law at George Mason University, or Francisco Marroquín University in Guatemala (disclaimer: I have affiliations with all three).

Or how about right-leaning podcasts and YouTube channels? They too compete with Harvard, and very often they have more influence on how people actually think. Comedy is another institution that often is right-leaning. I’ve also spent significant time with the leading AI models, and find they are considerably more centrist and objective than our institutions of higher education.

It is far from obvious that the ideas of Harvard will play such a dominant role in shaping the future of America. And given that is the case, why choose a destructive “solution” that will impose so much collateral damage on America’s future?

In other words, this is not necessarily a losing battle, and thus you do not need to try to burn Harvard to the ground. Nor must you despair that true reform is impossible. True reform can occur elsewhere, most likely on the internet. There is indeed something to be said for getting back at Harvard. But it can’t be about them losing—you too have to win. Like it or not, it’s time to start building.