Rorschach Economics

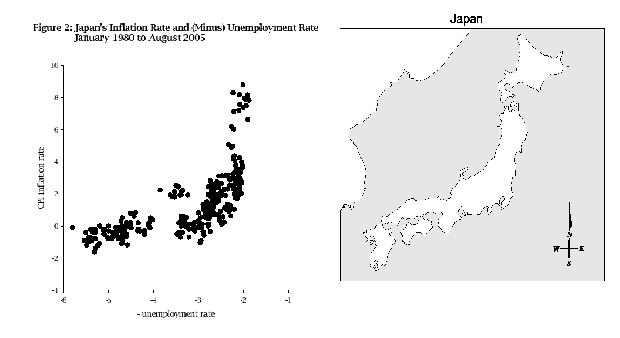

Gregor Smith of Queen’s University has discovered an amazing new relationship, Japan’s Phillips Curve Looks Like Japan. John Palmer of EclectEcon believes that the result may be systematic as he has discovered that Canada’s Phillip’s Curve looks like Canada.

Obviously these people are crazy. Smith and Palmer clearly do not understand Marshallian

macroeconomics – everyone knows that the Phillip’s Curve looks like this country.

Assorted links

1. Is Buffalo really hopeless?

2. Which paintings sell for more?, Financial Times Deutschland

3. Books to base your life on, by Ryan Holiday

4. One cheer for asset securitization, me on NPR Marketplace

5. Takes on fall books, on Slate, one segment is yours truly on the new Charles Taylor

Rational Expectations

I can report that the sugar high in children begins long before the sugar hits the bloodstream.

Why macroeconomics is not a science

The housing sector is down twenty percent and the price of oil is flirting with $90 a barrel, maybe $100 to come. Yet the quarterly growth rate was just reported at 3.9%, led by surges in consumer spending and exports. It is wrong to think we have turned the corner, but it is also wrong to think the doomsayers have been giving accurate predictions.

The economics of Halloween

A reform proposal from Kevin Hassett: "So let’s do something to reform Halloween. The first step would be for Halloween donors to give kids money instead of candy. Kids could then go to the supermarket the next day and binge on the candies they really like. That solution would get an A-plus in economics."

Linked here. But alas, in-kind transfers are often more efficient than cash gifts, and that holds for public policy as well. (Imagine giving "money to buy kidney dialysis," instead of "kidney dialysis," and see how many people fake kidney disease.) The candy transfer insures that a) mostly young kids do the asking, and b) at some point everyone just stops and goes home. I’ve long wanted to know how much movie attendance rises on Halloween evening, given that the real cost of going is suddenly and temporarily much lower.

Addendum: Here is a new paper on cash vs. in-kind transfers.

The economic value of teeth

Looks and height matter for economic outcomes, so why not teeth?

Healthy teeth are a vital and visible component of general well-being, but there is little systematic evidence to demonstrate any impact on the labor market. In this paper, we examine the effect of oral health on labor market outcomes by exploiting variation in access to fluoridated water during childhood. The politics surrounding the adoption of water fluoridation by local water districts suggests exposure to fluoride during childhood is exogenous to other factors affecting earnings. We find that children who grew up in communities with fluoridated water earn approximately 3% more as adults than children who did not. The effect is larger for women than men, and is almost exclusively concentrated amongst those from families of low socioeconomic status. Of the channels explored, we find that occupational sorting explains 14-23% of the effect, suggesting consumer and employer discrimination are the likely driving factors.

That is by Sherry Glied and Matthew Neidell; here is the paper on-line, note their findings are preliminary not final. Teeth seem to matter less for rich people because they have later chances to cover up — using money of course — for bad childhood teeth. The poor apparently remain stuck with their teeth problems. You might think that childhood exposure to fluoride is just proxying for quality of county and thus county human capital in some way, but the fluoride/earnings correlation seems to hold up even when variables are used to adjust for county quality. Can you dissent from a paper that writes:

…the anecdotes described above suggest that people who lack teeth may have trouble finding jobs.

I thank a loyal MR reader for the pointer.

Addendum: Here is Caplan (and Blinder) on the economics of teeth.

Borjas on Indoctrination

According to FIRE, The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education:

The University of Delaware subjects students in its residence halls to

a shocking program of ideological reeducation that is referred to in

the university’s own materials as a “treatment” for students’ incorrect

attitudes and beliefs….The university’s views are forced on students through a

comprehensive manipulation of the residence hall environment, from

mandatory training sessions to “sustainability” door decorations.

Students living in the university’s eight housing complexes are

required to attend training sessions, floor meetings, and one-on-one

meetings with their Resident Assistants (RAs). The RAs who facilitate

these meetings have received their own intensive training from the university, including a “diversity facilitation training” session at which RAs were taught, among other things,

that “[a] racist is one who is both privileged and socialized on the

basis of race by a white supremacist (racist) system. The term applies

to all white people (i.e., people of European descent) living in the

United States, regardless of class, gender, religion, culture or

sexuality.”

George Borjas writes:

Why am I super-sensitive to this? Because as a young boy I myself went through a one-year course in ideological reorientation. I attended an elite elementary Catholic school in Havana. Castro took over, the Catholic school was shut down, and I got transferred to a revolutionary school where the entire day was spent teaching Marxist-Leninist ideology. Luckily, this lasted only a year and I continued my education in Miami (where the entire school day was instead spent talking about the upcoming football game). I am certain that the blind zealotry that I saw in the young teacher’s eyes that year turned me off from that particular way of viewing the world for the rest of my life. One can only hope that many of the students forced to attend the re-education programs at Delaware and other universities react in the same way.

I’d be interested to hear from anyone with first hand experience of the University of Delaware program.

Clive Crook is blogging

Here, some of the early posts are responses to Krugman and DeLong. Clive has been the FT’s Washington columnist since April 2007 and is formerly of The Economist.

Assorted Links

- The

Impact of Milton Friedman on Modern Monetary Economics. A nice review by Edward Nelson and Anna Schwartz of Friedman’s thought and influence over monetary policy that also, in the author’s words, sets the record straight on Paul Krugman’s ‘Who was Milton Friedman.’

- The world may be getting smaller but big Americans are sinking the boats at Disney’s It’s a Small World.

- The Ayn Rand Lexicon is now online.

Carmen Laforet

Nada, her book, is even better, a true case of a rediscovered classic, now out in a first-rate English translation.

America fact of the day

America has 62 percent of the world’s [scientist] stars as residents, primarily because of its research universities which produce them.

Here is the paper, and, addended, here are non-gated versions.

School Choice: The Findings

This new Cato book is a good introduction to the empirical literature on vouchers and charter schools. For my taste it places too much weight on standardized tests, but admittedly that is the main way to compare educational results over time or across countries. I believe the lax nature of government schooling in the U.S. often leaves the upper tail of the distribution free to dream and create, but I would not wish to push that as an argument against vouchers. If you’re interested in bad arguments against vouchers, and their rebuttals, Megan McArdle offers a long post.

Can super-agents raise player salaries?

Robert, a loyal MR reader, asks:

I was recently

reading about ARod’s decision to leave the Yankees. The article

mentioned "superagent Scott Boras." It’s widely believed in the sports

community that Boras has the ability to increase the salaries beyond

what they would get with a regular agent. Considering that there are

only 30-odd teams that might want a player, I find it hard to believe

that an agent could make such a big difference.

I know more about Mark Alarie than ARod, but super-agents may matter through the following mechanisms:

1. The super-agent manages an otherwise incompetent or unruly player. The agent is about improving the quality of the player as much as extracting surplus from the team.

2. A super-agent, especially if he has repeat business with teams, may credibly certify the unobservable qualities of players, even star players.

3. Boras may be very good at marketing his players to management and getting owners to open up their pocketbooks.

4. If Boras represents multiple stars, clubs will be reluctant to cross him. The equilibrium here is tricky. But if the agent has discretionary power to steer a player to one equal offer or the other, and the club reaps surplus from each player, a club may overbid for one player to stay on the agent’s good side and receive favorable discretionary treatment later on. Repeat dealings with the agent also mean that the club is more likely to follow through on its implicit commitments to both the player and the agent.

5. Robert suggests that some (non-super) agents may in fact be in league with the owners, not the players.

Can you think of other possible mechanisms?

Addendum: Here is J.C. Bradbury on Boras. And here is a New Yorker story on Boras, courtesy of John de Palma.

How To Talk About Books You Haven’t Read

What a wonderful title. This new sensation, by French intellectual superstar Pierre Bayard, tells how to liberate our reading habits from the oppression of our most formidable peers (we carry around books to look cool) and more importantly from our own ever-more-demanding selves, which pursue the perfect reading experience but for largely misconceived and self-destructive Freudian reasons; rather than improving our reading, we should instead perfect a new kind of "anti-reading," and as part of a broader program of reconciling antinomies, de-objectifying the book, revising Barthes to fit a new and partially unhidden world where structures can be liberating, and uncovering the not yet fully recognized Proustian roots of the modern sensibility.

Highly recommended, it comes out tomorrow.

What does a post under the fold signal?

Lee, a loyal MR reader (by RSS, it seems), writes:

I am also protesting these partial posts! They are mildly inconvenient!

Sadly, when part of an MR post is below the fold, only the top part is fed into RSS. The vast majority of our posts are full posts, I use partial posts for two reasons.

First, sometimes I wish to keep a more important or more typical post close to the top of the page. This signals to new readers what we are about; I don’t want Eric Maskin visiting MR for the first time and thinking it is a blog mostly about romantic piano music. Keeping an older post toward the top of the page also keeps the comments flowing.

Second, putting a post under the fold signals that the post will not interest most of you. In equilibrium, only those of you who really care about the post title should incur the cost of either clicking on the bottom part or leaving RSS and visiting the site, and then clicking, to read it. You are supposed to be put off from reading it (except for the few dedicated Nyiregyhazi fans who read MR, are there any?; it does not suffice to share his addictions). But perhaps I am naive here, and telling people "this is quirky stuff that won’t interest most of you" in fact generates interest.

But not today: Ideally, I would have put most of this post…er…under the fold.