Results for “unemployment” 701 found

Larry Summers on technological unemployment in history

This bit is from the Q&A session:

LS: So, I guess I think there is both a, you know, Keynes as usual I think was pretty smart and you know, Keynes began his essay on economic possibilities for our grandchildren by saying that there was this really pressing cyclical problem that had to do with demand which was really important but not all that profoundly fundamental. And there was this more fundamental thing which was that technology was marching on and he thought the dis-employment effects would show up as everybody working 15 hour weeks. And it doesn’t look like that’s quite what they’re showing up as. But the basic idea that technological progress comes with reduced labor input, sometimes it’s early retirement, sometimes it’s people who aren’t able to get themselves employed, sometimes, it’s lower hours, but that is basically the story of the last 150 years.

So, I would not back off of my putting a lot of weight on technology as something important here.

The talk and dialogue (pdf) are on macro more generally, interesting throughout. In general I believe there should be more transcribed and summarized dialogues, both the NBER and Brookings have had intellectual success with that format.

Claims about electricity adoption and technological unemployment

This is from a recent working paper (pdf) by Miguel Morin:

When the adoption of a new labor-saving technology increases labor productivity, it is an open question whether the economy adjusts in the medium-term by decreasing employment or increasing output. This paper studies the effects of cheaper electricity on the labor market during the Great Depression. The first-stage of the identification strategy uses geography as an instrument for changes in the price of electricity and the second-stage uses labor market outcomes from the concrete industry—a non-traded industry whose location decisions are independent of the instrument. The paper finds that electricity was an important labor-saving technology and caused an increase in capital intensity and labor productivity, as well as a decrease in the labor share of income. The paper also finds that firms adjusted to higher labor productivity by decreasing employment instead of increasing output, which supports the theory of technological unemployment.

You will note of course that the short-, medium- and long-run effects here are quite different, and of course electricity is a major boon to mankind. Still, technological unemployment is not just the fantasy of people who have failed to study Ricardo.

Here is a short summary of the paper, via Romesh Vaitilingam.

What is China’s Unemployment Rate?

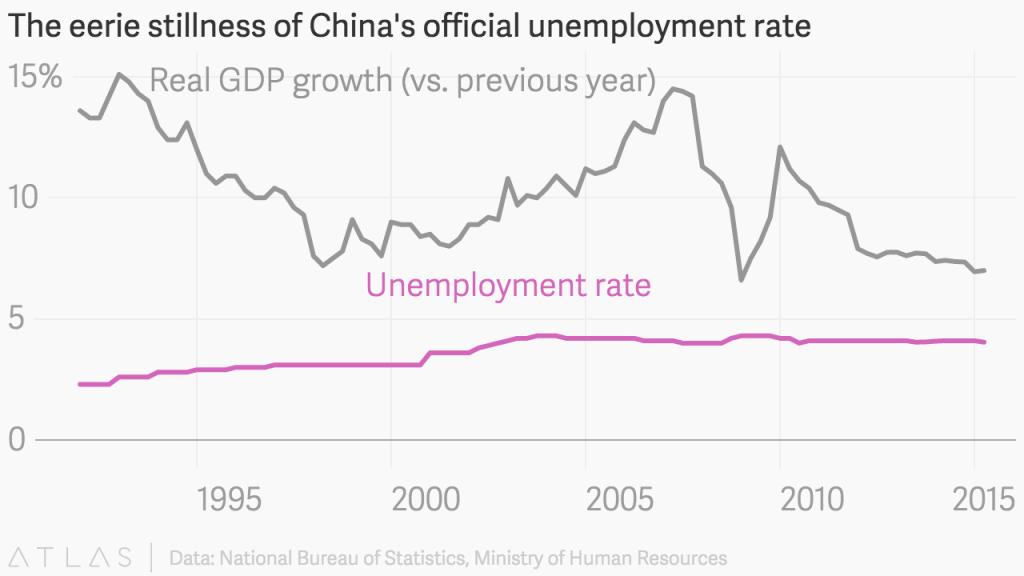

What is China’s Unemployment Rate? 4.1% For what month, what year? Doesn’t matter the answer is still 4.1%. That’s a slight exaggeration but for the last 3 years the unemployment rate has been 4.1% almost every month. Indeed, since 2002 the official unemployment rate has varied between 3.9% and 4.3%, an absurdly smooth series.

In contrast to the unemployment rate, China’s GDP growth rate has had massive swings. As a piece in Quartz puts it the unemployment rate exhibits an eerie stillness.

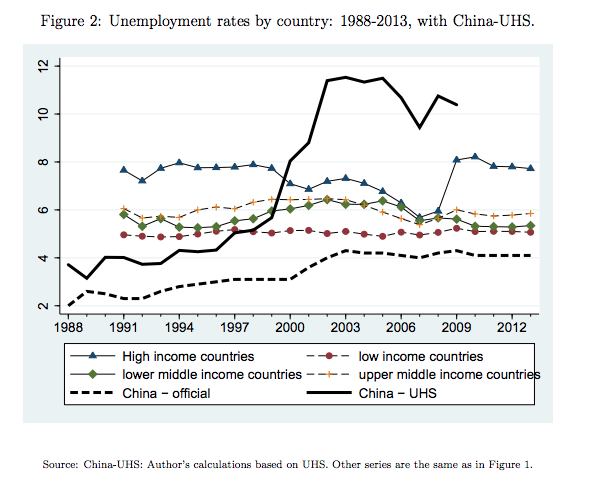

A new NBER working paper uses a newly available household survey and finds a very different series–the China-UHS series shown in black below. According to these estimates China’s unemployment rate shot up to around 11% in 2002 and has been nearly that high at least until 2009 when unfortunately the new series ends.

So how high is Chinese unemployment today? No one knows but it could well be closer to 10% than to 4.1%.

Keep an eye on China and don’t be surprised by the unexpected. In China it’s not just the unemployment rate that is more volatile than it appears.

Declining Desire to Work and Downward Trends in Unemployment and Participation

That is the next (and for me final) NBER paper from the macro workshop, by Barnichon and Figura, the pdf is here. Their main claim is quite startling, and very important if true. Here is the abstract:

The US labor market has witnessed two apparently unrelated trends in the last 30 years:a decline in unemployment between the early 1980s and the early 2000s, and a decline in labor force participation since the early 2000s. We show that a substantial factor behind both trends is a decline in desire to work among individuals outside the labor force, with a particularly strong decline during the second half of the 90s. A decline in desire to work lowers both the unemployment rate and the participation rate, because a nonparticipant who wants to work has a high probability to join the unemployment pool in the future, while a nonparticipant who does not want to work has a low probability to ever enter the labor force. We use cross-sectional variation to estimate a model of nonparticipants’ propensity to want a job, and we find that changes in the provision of welfare and social insurance, possibly linked to the mid-90s welfare reforms, explain about 50 percent of the decline in desire to work.

We conjecture that two mechanisms could explain these results. First, the EITC expansion raised family income and reduced secondary earnersís (typically women) incentives to work. Second, the strong work requirements introduced by the AFDC/TANF reform would have, through a kind of “sink or swim” experience, left the “weaker” welfare recipients without welfare and pushed them away from the labor force and possibly into disability insurance.

Optimal life cycle unemployment insurance

It seems we should index unemployment benefits to a person’s age. For the liquidity-constrained, human capital-investing young, we don’t want to rush them into unsuitable jobs. The older workers — that’s another matter. Michelacci and Ruffo report:

We argue that US welfare would rise if unemployment insurance were increased for younger and decreased for older workers. This is because the young tend to lack the means to smooth consumption during unemployment and want jobs to accumulate high-return human capital. So unemployment insurance is most valuable to them, while moral hazard is mild. By calibrating a life cycle model with unemployment risk and endogenous search effort, we find that allowing unemployment replacement rates to decline with age yields sizeable welfare gains to US workers.

The AER version is here. Ungated versions are here. Elsewhere Ben Casselman considers some ways that unemployment has changed, and what that may mean for benefits.

How much did cutting unemployment benefits help the labor market?

Quite a bit. There is a new NBER Working Paper on this topic by Hagedorn, Manovskii, and Mitman, showing (once again) that most supply curves slope upward, here is one key part from the abstract:

In levels, 1.8 million additional jobs were created in 2014 due to the benefit cut. Almost 1 million of these jobs were filled by workers from out of the labor force who would not have participated in the labor market had benefit extensions been reauthorized.

There is an ungated copy here (pdf). Like the sequester, this is another area where the Keynesian analysts simply have not proven a good guide to understanding recent macroeconomic events.

Good sentences about male and female technological unemployment

I think that if you look only at males in isolation, you will see this in the data. That is, men are working much less than they used to. For some men, this leisure is very welcome, but for others it is not. In that sense, I think that we should look at the [technological unemployment] fears of the early 1960s not as quaint errors but instead as fairly well borne out.

For women, the story since the 1960s is different. In the economy as a whole, the share of labor devoted to preparing food, washing clothes, and cleaning house has gone down. Also, a higher share of the remaining work in these areas is coming from the market, via restaurants and cleaning services, rather than from unpaid female labor. The upshot is that, from the 1960s to about 2000, we saw a continuation of the trend for women to increase their share of market work and reduce their non-market labor. So, while men were increasing their leisure, women were increasing their market work. Combining men and women, you would not see a decline in market work.

It seems that around 2000, the trend for more market work by women reached its peak, making the trend toward technological unemployment more visible. From now on, what was happening to men before will be what happens to the total labor force. That is, leisure will go up, and some of it will be less than voluntary.

That is from Arnold Kling.

Was there mismatch unemployment during the Great Recession?

I remember this question being debated extensively circa 2009-2011, and those who said there was a (limited) role for mismatch unemployment were mocked pretty mercilessly. Well, Sahin, Song, Topa, and Violante have a piece in the new American Economic Review entitled “Mismatch Unemployment.” (You can find various versions here.) It’s pretty thorough and state of the art. Their conclusion:? “…mismatch, across industries and three-digit occupations, explains at most one-third of the total observed increase in the unemployment rate.” The people thrown out of work could not be matched as well as the unemployed workers of the past.

Much of the matching problem was for skilled workers, college graduates, and in the Western part of the country. Geographical mismatch unemployment did not appear to be significant. Now, “at most one-third” is not the main problem, but it is not small beans either. That’s a lot of people out of work because of matching problems.

Again, the Great Recession arose from a confluence of supply and demand problems.

Immigration Granger-causes neither unemployment nor growth

So argues a new paper (pdf) by Ekrame Boubtane, Dramane Coulibaly, and Christophe Rault, the abstract is here:

This paper examines the causality relationship between immigration, unemployment and economic growth of the host country. We employ the panel Granger causality testing approach of Konya (2006) that is based on SUR systems and Wald tests with country specific bootstrap critical values. This approach allows to test for Granger-causality on each individual panel member separately by taking into account the contemporaneous correlation across countries. Using annual data over the 1980-2005 period for 22 OECD countries, we find that, only in Portugal, unemployment negatively causes immigration, while in any country, immigration does not cause unemployment. On the other hand, our results show that, in four countries (France, Iceland, Norway and the United Kingdom), growth positively causes immigration, whereas in any country, immigration does not cause growth.

This result reflects two broader lessons. First, at the margin the major benefits from migration are to the migrants. Second, again at the margin, most policy changes matter less than you think they will.

Hat tip goes to Ben Southwood.

Why is there so much unemployment in Gaza?

Assaf Zimring writes to me:

Since we tend to associate high unemployment with any economic calamity, people don’t seem to think a lot about why we see very high unemployment in Gaza. But I am puzzled by it. How come an economy with such tremendous shortages fails to employ 40% of its workers in an attempt to meet these shortages?

Has the (by now, fairly loose) blockade pushed the MPL to zero for 40% of workers? Is it uncertainty that stops investment? Did large aid payments (in some years – 50% of GDP) cause some kind of a Dutch disease of an epic scale (though I am not sure that would lead to unemployment)? I wonder if you have any thoughts about that.

At the first link you will find some interesting papers by Assaf on the Gaza blockade and other Gaza shocks. One option of course is simply that hardly anyone is really employed, although there is massive underemployment in grey and black market economies, including for the digging of tunnels and subsistence agriculture.

Why are so many people still out of work?: the roots of structural unemployment

Here is my latest New York Times column, on structural unemployment. I think of this piece as considering how aggregate demand, sectoral shift, and structural theories may all be interacting to produce ongoing employment problems. “Automation” can be throwing some people out of work, even in a world where the theory of comparative advantage holds (more or less), but still this account will be partially parasitic on other accounts of labor market dysfunction. For reasons related to education, skills, credentialism, and the law, it is harder for some categories of displaced workers to be reabsorbed by labor markets today.

Here are the two paragraphs which interest me the most:

Many of these labor market problems were brought on by the financial crisis and the collapse of market demand. But it would be a mistake to place all the blame on the business cycle. Before the crisis, for example, business executives and owners didn’t always know who their worst workers were, or didn’t want to engage in the disruptive act of rooting out and firing them. So long as sales were brisk, it was easier to let matters lie. But when money ran out, many businesses had to make the tough decisions — and the axes fell. The financial crisis thus accelerated what would have been a much slower process.

Subsequently, some would-be employers seem to have discriminated against workers who were laid off in the crash. These judgments weren’t always fair, but that stigma isn’t easily overcome, because a lot of employers in fact had reason to identify and fire their less productive workers.

Under one alternative view, the inability of the long-term unemployed to find new jobs is still a matter of sticky nominal wages. With nominal gdp well above its pre-crash peak, I find that implausible for circa 2014. Besides, these people are unemployed, they don’t have wages to be “sticky” in the first place.

Under a second view, the process of being unemployed has made these individuals less productive. Under a third view (“ZMP”), these individuals were not very productive to begin with, and the liquidity crisis of the crash led to this information being revealed and then communicated more broadly to labor markets. I see a combination of the second and third forces as now being in play. Here is another paragraph from the piece:

A new paper by Alan B. Krueger, Judd Cramer and David Cho of Princeton has documented that the nation now appears to have a permanent class of long-term unemployed, who probably can’t be helped much by monetary and fiscal policy. It’s not right to describe these people as “thrown out of work by machines,” because the causes involve complex interactions of technology, education and market demand. Still, many people are finding this new world of work harder to navigate.

Tim Harford suggests the long-term unemployed may be no different from anybody else. Krugman claims the same. (Also in this piece he considers weak versions of the theories he is criticizing, does not consider AD-structural interaction, and ignores the evidence presented in pieces such as Krueger’s.) I think attributing all of this labor market misfortune to luck is unlikely, and it violates standard economic theories of discrimination or for that matter profit maximization. I do not see many (any?) employers rushing to seek out these workers and build coalitions with them.

There were two classes of workers fired in the great liquidity shortage of 2008-2010. The first were those revealed to be not very productive or bad for firm morale. They skew male rather than female, and young rather than old. The second affected class were workers who simply happened to be doing the wrong thing for shrinking firms: “sorry Joe, we’re not going to be starting a new advertising campaign this year. We’re letting you go.”

The two groups have ended up lumped together and indeed a superficial glance at their resumes may suggest — for reemployment purposes — that they are observationally equivalent. This discriminatory outcome is unfair, and it is also inefficient, because some perfectly good workers cannot find suitable jobs. Still, this form of discrimination gets imposed on the second class of workers only because there really are a large number of workers who fall into the first category.

Here is John Cassidy on the composition of current unemployment. Here is Glenn Hubbard with some policy ideas.

The North Carolina unemployment insurance experiment may be looking up

The benefits have been stopped, and there has been much recent debate over how well this is working to stimulate reemployment. This new study is from Kurt Mitman, who is a doctoral candidate at U. Penn and an NBER research associate, here is his summary:

1. Evidence from the establishment survey confirms a substantial increase in employment in North Carolina following the unemployment insurance reform.

2. The increase in payroll employment reported by the sample of North Carolina employers is smaller than the increase in employment reported by workers in the household survey.

3. The increase in employment [is] driven by the private service sector.

4. A comparison of the growth in employment between North Carolina and the adjacent states in Figure 5 reveals a similar growth in the post-reform period between the two Carolinas, which is much faster growth than in Virginia.

5. Results in Table 3 reveal a mild tendency toward higher weekly hours post reform and little change in wages and earnings.

The full piece is here (pdf). This seems to me our best understanding of the admittedly limited data to date.

Neumark and Wascher on minimum wages and youth unemployment

Here is the abstract from their piece from 2003 (pdf):

We estimate the employment effects of changes in national minimum wages using a pooled cross-section time-series data set comprising 17 OECD countries for the period 1975-2000, focusing on the impact of cross-country differences in minimum wage systems and in other labor market institutions and policies that may either offset or amplify the effects of minimum wages. The average minimum wage effects we estimate using this sample are consistent with the view that minimum wages cause employment losses among youths. However, the evidence also suggests that the employment effects of minimum wages vary considerably across countries. In particular, disemployment effects of minimum wages appear to be smaller in countries that have subminimum wage provisions for youths. Regarding other labor market policies and institutions, we find that more restrictive labor standards and higher union coverage strengthen the disemployment effects of minimum wages, while employment protection laws and active labor market policies designed to bring unemployed individuals into the work force help to offset these effects. Overall, the disemployment effects of minimum wages are strongest in the countries with the least regulated labor markets.

Unemployment benefits and Google job search

I had not known of this Scott R. Baker and Andrey Fradkin paper until recently, here is the abstract:

The large-scale unemployment caused by the Great Recession has necessitated unprecedented increases in the duration of unemployment insurance (UI). While it is clear that the weekly payments are beneficial to recipients, workers receiving benefits have less incentive to engage in job search and accept job offers. We construct a job search activity index based on Google data which provides the first high-frequency, state-specific measure of job search activity. We demonstrate the validity of our measure by benchmarking it against the American Time Use Survey and the comScore Web-User Panel, and also by showing that it varies with hypothesized drivers of search activity. We test for search activity responses to policy shifts and changes in the distribution of unemployment benefit duration. We find that search activity is greater when a claimant’s UI benefits near exhaustion. Furthermore, search activity responses to the passage of bills that increase unemployment benefits duration are negative but short-lived in most specifications. Using daily data, we estimate that an increase by 1% of the population of unemployed receiving additional benefits results in a decrease in aggregate search activity of 1.7% lasting only one week.

One way (not the only way) of reading these results is to wonder if some of the unemployed feel they ought to increase their shirking in response to an extension of benefits, but they actually don’t really want to do so. They shirk a bit more, for a short while, not to feel like fools, and then return either to active search or fruitless despondent search, as the case may be. For better or worse, habit dies hard.

For the pointer I thank John Horton.

Conor Sen, by the way, tells us that “ask for a raise” is at a post-recession high on Google Trends.

Kebko on North Carolina’s unemployment insurance experiment

#5: I think Evan is being a bit too broad with his interpretation of the labor market in North Carolina. There have been two distinct phases of labor force adjustments:

1) Between the passage of the law and its implementation, there was a small decrease in unemployment. But, mostly, on net, there was a decrease in employment and a corresponding decrease in labor force participation. The movement was from employment to not-in-labor-force. I don’t know if there is a straightforward way to interpret this, but I don’t believe Evan is addressing it cleanly in the article.

2) After the implementation of the law, labor force participation stabilized. Since that time, there has been a decrease in unemployment and an increase in the Employment to Population ratio. People are moving from unemployment to employment.

The first phase could have a number of interpretations. The second phase is clearly what opponents of Emergency Unemployment Insurance would have predicted. At this point, I think we still need to give it a few months to see if the rebound in the employment to population ratio continues. If it does, then this article by Evan will have been unfortunate.

Here is my post on the issue, with some graphs: http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2013/12/a-natural-experiment-on-emergency.html