Monday assorted links

1. New languages for Google Translate.

3. Eric Topol on the current state of the virus.

4. A guy on YouTube mimicking John Lennon, with Yoko and George Harrison, singing Paul McCartney solo songs. And now here is “John Lennon” doing “Band on the Run” album.

5. David Boaz honors George H. Smith. And David Henderson on George.

6. Management secrets of Anna Wintour (Bloomberg).

Infant Formula, Price Controls, and the Misallocation of Resources

I’ve been reluctant to write about the shortage of infant formula simply because it’s so tiring to say the same thing over and over again. Obviously, this is a classic case where the FDA should allow imports of any food or baby formula approved by a stringent authority. (Here’s the US Customs and Border Patrol bragging about how they nabbed 588 cases of infant formula from Germany and the Netherlands as if it were cocaine.) Scott Lincicome has an excellent run down which covers not just the FDA but the problems caused by trade regulation and the WIC program as well.

I’ve been reluctant to write about the shortage of infant formula simply because it’s so tiring to say the same thing over and over again. Obviously, this is a classic case where the FDA should allow imports of any food or baby formula approved by a stringent authority. (Here’s the US Customs and Border Patrol bragging about how they nabbed 588 cases of infant formula from Germany and the Netherlands as if it were cocaine.) Scott Lincicome has an excellent run down which covers not just the FDA but the problems caused by trade regulation and the WIC program as well.

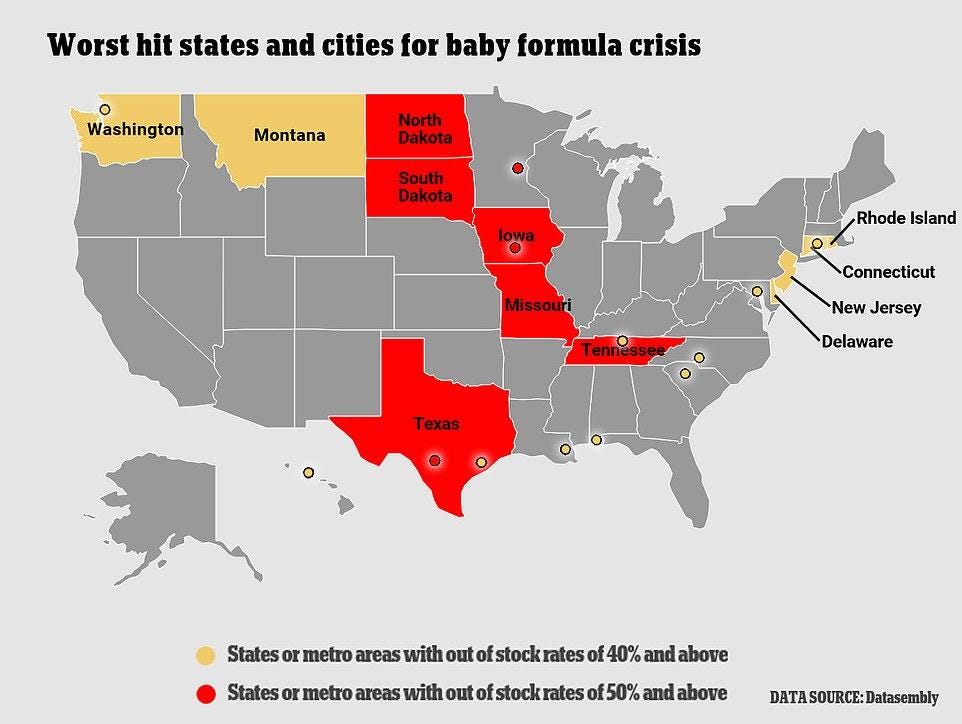

What I want to do is focus on something less discussed: Why does the shortage vary across the country and even city by city?

I believe one reason is implicit price controls, either due to fear of regulatory backlash, regulatory constraints through other programs, or a misplaced desire not to upset consumers.

Price controls create shortages–that much is well known–but they also create a misallocation of goods. No doubt you have seen pictures from the 1970s of long lines of cars waiting to get gasoline. But there weren’t lineups everywhere at all times–rather we had the strange situation where there were shortage of gasoline in some places while, just a hundred miles away, there was plenty. Or shortages one day and surpluses the next.

Prices rationally allocate goods across space and time in response to shifts in demand and supply. If demand increases in one place, for example, prices rise, creating an incentive to bring in supplies from elsewhere. A rising price signals where supplies are needed and creates an incentive to deliver. Or, as Tyler and I put it, A price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive. A price controlled below the market price creates a shortage and it also kills the signaling and incentive function of prices. The result is allocational chaos: Shortages in some places and times and excess supply in other places and times.

In fact, price controls in a capitalist economy give you a window onto a planned economy. If you think of communism as a system of universal price controls this allocation chaos is the essence of why a communist state cannot rationally allocate resources.

Tyler and I discuss allocational chaos in our chapter on price controls in Modern Principles of Economics. See also this excellent video.

Russia fact of the day

Russia has stopped publishing detailed monthly trade statistics. But figures from its trading partners can be used to work out what is going on. They suggest that, as imports slide and exports hold up, Russia is running a record trade surplus.

On May 9th China reported that its goods exports to Russia fell by over a quarter in April, compared with a year earlier, while its imports from Russia rose by more than 56%. Germany reported a 62% monthly drop in exports to Russia in March, and its imports fell by 3%. Adding up such flows across eight of Russia’s biggest trading partners, we estimate that Russian imports have fallen by about 44% since the invasion of Ukraine, while its exports have risen by roughly 8%.

Here is more from The Economist, and that is why the ruble has maintained its value:

As a result, analysts expect Russia’s trade surplus to hit record highs in the coming months.

Why don’t nations buy more territories from each other?

Here is a rather underwhelming list of such purchases in recent times. West Germany buys three islands from the Netherlands in 1963? Pakistan buys Gwadar from Muscat and Oman in 1958. America buys the Danish West Indies in 1916. In 1947, though the Soviet Union bought part of Lapland in Finland to enable a hydroelectric plant.

We all know about the Louisiana Purchase. But that’s it since 1916!? Is Wikipedia failing us? I don’t think so.

Are there really no good Coasean trades between the two Irelands? Israel and the Palestinians? Armenia and Azerbaijan? How about Chile selling Bolivia a wee bit of coastline? I can think of a few reasons why territory purchases are these days so hard to pull off.

1. Incoming revenue is subject to a fiscal commons effect. Some crummy noble does not get to spend it on himself. And voters take government revenue for granted in most cases, and so do not perceive an increase in their expected retirement benefits from selling land to foreign powers.

2. In earlier times, a lot of land transactions were motivated by “they’re going to take it from us anyway, sooner or later.” Did Napoleon really think he could hold on to all that land? No. He wisely got out, though sadly subsequent French governments did not do “buy and hold.” Not to mention the Florida Purchase Treaty and Guadalupe Hidalgo. At least until lately, wars of conquest have been in decline and that has meant a corresponding decline in country-to-country land transactions as well.

3. First mass media and then social media have succeeded in making land boundaries more focal to the citizenry. Say Northern Ireland today wanted to sell a single acre to the Republic of Ireland. This would be seen as a precedent, rife with political implications, and it would be hard to evaluate the transaction on its own terms. Trying to sell a county would be all the more so. Just look at the map — should there really be so much of “Northern” Ireland to the south of ROI? Donegal, Derry, etc. — status quo bias, are we really at an optimum point right now?

4. Contested territories today often involve low levels of trust. Selling pieces of the Irelands back and forth is likely enforceable (but does ROI want any of it?), but an Israel-Palestine deal is not. Israel prefers to simply move the goalposts by increasing the settlements in the westward direction. What is really the gain from pressuring one of the Palestinian leaders to sign a piece of paper recognizing this? Most likely it would ensure his assassination and simply enflame tensions further. Both parties might prefer unilateral action over a deal.

5. Land in general is far less valuable than in earlier times. In theory, that could make it either easier or harder to sell land, but if some of the transactions costs (see above) are constant or rising in magnitude, that will make it harder. Let’s say Colombia raised the funds to buy back part of the Darien gap — whoop de doo! The country has plenty of empty land as it is. The whole notion of Lebensraum, and I don’t just mean in its evil Nazi form, has taken a beating since World War II.

6. Russia and China block some deals that might make sense, or maybe America blocks them too. Just run a Google search on “Arctic.” China is doing the investing, but we won’t let them own it. Russia doesn’t want America to own it. Everything thinks Canadian control or ownership doesn’t amount to much. Indigenous groups claim parts of it, but they cannot exercise effective control. And so the whole region and issue festers and stagnates.

7. Consider a deal that does make sense: the U.S. buying Greenland from the Greenlanders and also Denmark. Can we really in essence pay the 56,000 or so residents to give up their country and territory? I am no expert on the politics there, but I suspect they are unwilling to vote their pocketbook. (For one thing, I don’t see them posting a price on eBay or holding a garage sale.) How about skipping the vote and just offering them free condos in Miami? Let’s do it! Still, you can see the problem.

What else? And can you think of any current issues where a transactional approach might actually work?

ESG Versus Innovation

Some wise words on ESG and innovation from the excellent Bart Madden:

Excessive focus on looking good in the short term via ESG metrics can be at cross-purposes with a long-term planning horizon keyed to innovation. A sizable portion of a firm’s major innovations may not move the needle much as to ESG metrics but may score high in the eyes of customers as to value creation (and quite possibly improve their customers’ ESG performance). Recent research reveals a tendency during quarterly earnings conference calls for those managements who have reported weaker-than-expected profits to talk less about financial results and more about their ESG progress.31 Keep in mind that innovation is the key to sustainable progress that jointly delivers on financial performance and taking care of future generations through environmental improvements.

Addendum: Bart has a history of smart investing.

Sunday assorted links

1. Sheikh Khalifa of UAE passes away (NYT).

2. George H. Smith has passed away.

3. The Economist on India’s economy, a good feature story.

4. Regulatory obstacles to flying electric vehicles (WSJ).

5. Is current comedy favoring the right wing?

How much should you criticize other people?

I mean in private conversation, not in public discourse, and this is not to their faces but rather behind their back. And with at least a modest amount of meanness, I am not talking about criticizing their ideas. Here are some reasons not to criticize other people:

1. “Complain less” is one of the very best pieces of wisdom. That is positively correlated with criticizing other people less, though it is not identical either.

2. If you criticize X to Y, Y wonders whether you criticize him to others as well. This problem can increase to the extent your criticism is biting and on the mark.

3. Criticizing others is a form of “devalue and dismiss,” and that tends to make the criticizing people stupider. If I consider the columnists who pour a lot of energy into criticizing others, even if they are sometimes correct, it isn’t so pretty a picture where they end up.

4. If X criticizes Y, it may get back to Y and Y will resent X and perhaps retaliate.

5. Under some moral theories, X is harming Y if X criticizes Y, Y doesn’t find out, and Y faces no practical penalties from that criticism (for an analogy, maybe a wife is harming her husband if she has a secret affair and he never finds out about it).

Here are some reasons to criticize others:

4. Others may deserve the criticism, and surely there is some intrinsic value in speaking the truth and perhaps some instrumental value as well.

5. Criticizing others is a way of building trust. In a three-way friendship with X, Y, and Z, if X establishes that he and Y can together criticize Z, that may boost trust between Y and X, and also increase X’s relative power in the group. Criticizing “Charles Manson” doesn’t do this — you’ve got to take some chances with your targets.

6. Criticizing others may induce people to fear you in a useful way. They may think if they displease you, you will criticize them as well.

7. Perhaps something or somebody is going to be criticized no matter what. If you take the lead with the criticism, that is a signal of your leadership potential.

What else? Is there anything useful written on this topic?

I favor bird consequentialism

We have to be more willing to disrupt current animal habitats when building wind or hydroelectric power. That means, to put it bluntly, that we have to be more willing to kill animals. Erecting wind turbines, for instance, often leads to the death of some number of birds. To favor more wind turbines is not to support the death of more birds; it is to support a more robust long-term supply of green energy — which would benefit birds (and of course humans too)…

I favor a much more proactive policy agenda to boost the welfare of animals. That could include subsidies to new “artificial meat” technologies, more research into animal diseases and pandemics, even research into the possibility of bringing back extinct animals through genetic engineering. The US should also have more consistent enforcement of animal cruelty laws.

Protecting birds by limiting wind power is about the most damaging way to try to serve nature and the environment. It is a way of pretending to care about birds. It is also an illustration of how so many institutions are so dedicated to protecting entrenched interests — whether they are in the political or natural world.

Here is the rest of my Bloomberg column. Bell the cat! You should be the one who gets to kill the bird. And while we’re at it, let’s ban octopus farms too.

Who is rich in America?

We now know who is rich in America. And it’s not who you might have guessed.

A groundbreaking 2019 study by four economists, “Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century,” analyzed de-identified data of the complete universe of American taxpayers to determine who dominated the top 0.1 percent of earners.

The study didn’t tell us about the small number of well-known tech and shopping billionaires but instead about the more than 140,000 Americans who earn more than $1.58 million per year. The researchers found that the typical rich American is, in their words, the owner of a “regional business,” such as an “auto dealer” or a “beverage distributor.”

That is from Seth Stephens-Davidowitz (NYT), who covers some other interesting wealth/happiness topics as well.

Covid and reverse discrimination

Earlier in the pandemic, you might have had various theories about who was most likely to infect you, who was most likely not to be vaccinated/boosted, or who was most likely to have been going around without proper mask precautions. Perhaps you went to some greater lengths, either large or small, to avoid those people or to take greater precautions around them. Today, at least in most of the United States, we have entered the funny “reverse discrimination” phase of the pandemic. The higher status the person, the more you should beware! In the last few weeks, some of the higher status people I know have come down with Covid (they are all fine, to be clear), and at much higher rates than “people I know” were getting Covid before.

So behave accordingly, have a beer with your garbage collector, and I suspect this moment won’t last but another week or two.

Slovakian Asks Good Questions About American Suburbs

My questions are:

What do you actually do? Are you always stuck inside? What did you do when you were a child and couldn’t drive?

Why do you have these sorts of strange regulations? Are your officials so incompetent? Is this due to lobbying from car or oil companies? I don’t get it.

Why is there no public transport? It seems like the only thing is the yellow school bus, idk.

He says there can be only one family houses. Why? Why can’t you have idk a commie block in the middle of such a suburb? Or row houses or whatever.

Why are there no businesses inside these? I mean, he says it’s illegal, just why? If I lived in such a place, I’d just buy a house next to mine and turn it into a tavern or a convenience store or whatever. Is that simply not possible and illegal?

These places have front and backyards. But they’re mostly empty. Some backyards have a pool maybe, but it’s mostly just green grass. Why don’t you grow plants in your yards? Like potatoes, cucumbers, tomatoes or whatever. Why do you own this land, if you never use it?

Originally from Reddit.

Saturday assorted links

1. Thomas Schelling 1963-64 syllabus and final exam.

3. Transitioning to post-quantum cryptography?

6. “The FDA won’t allow European formulas to be sold here because of inane labeling concerns…”

7. “New funding effort will deploy a corps of scientist ‘scouts’ to spot innovative ideas.”

8. Biden administration seeking to stymie charter schools (NYT). #TheGreatForgetting

What I’ve been reading

1. Paul Strathern, The Florentines: From Dante to Galileo. It is not just Dante and Galileo, there is also Boccaccio, Petrarch, Machiavelli, Giotto, Botticelli, Leonardo, Fra Filippo Lippi, Michelangelo, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, and many more, all from one small region of Italy. This book doesn’t answer how that all happened, but it is perhaps the best survey of the magnitude and extent of what happened, recommended and readable throughout, good as both an introduction and for the veteran reader of books about Florence. While we are at it, don’t forget Pacioli and the first treatise on double-entry bookkeeping.

2. Geoff Dyer, The Last Days of Roger Federer: And Other Endings. A hard book to explain, mostly it is about how careers end or collapse or implode, only some of it is about Federer. “De Chirico lived till he was ninety but produced little of value after about 1919.” Calling a book a “tour de force” almost certainly means it isn’t, but this book…is a tour de force.

3. Mason Currey, Daily Rituals: How Artists Work. One or two-page sections on the work habits of famous artists, the selection of names is intelligent and this book is like potato chips in the good sense of the term.

4. Asa Hoffman with Virginia Hoffman, The Last Gamesman: My Sixty Years of Hustling Games in the Clubs, Parks and Streets of New York. A fun look back at the NYC chess world of the 1970s and trying to make a living as a chess and Scrabble hustler. I knew Hoffman a bit back then, and even as a kid I wondered “is this guy happy?” In the book he says he has largely been happy! I am still wondering. Maybe the secret is to play a game many discrete times where your losses are temporary and swamped by rapidly forthcoming wins? I am reminded of the words of the recently deceased grandmaster and centenarian Yuri Averbakh (NYT): “The main thing was that I never obtained great pleasure from winning,’’ he wrote. “Clearly, I did not have a champion’s character. On the other hand, I did not like to lose, and the bitterness of defeat was in no way compensated for by the pleasure of winning.”

5. Christopher Duggan, The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy since 1796. A good and very useful general introduction to the history of the latter part of the story of Italy.

What should I ask Vaughn Smith?

I will be doing a Conversation with him so what should I ask? He is a carpet cleaner. And there is this:

“So, how many languages do you speak?”

“Oh, goodness,” Vaughn says. “Eight, fluently.”

“Eight?” Kelly marvels.

“Eight,” Vaughn confirms. English, Spanish, Bulgarian, Czech, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian and Slovak.

“But if you go by like, different grades of how much conversation,” he explains, “I know about 25 more.”

Vaughn glances at me. He is still underselling his abilities. By his count, it is actually 37 more languages, with at least 24 he speaks well enough to carry on lengthy conversations. He can read and write in eight alphabets and scripts. He can tell stories in Italian and Finnish and American Sign Language. He’s teaching himself Indigenous languages, from Mexico’s Nahuatl. to Montana’s Salish. The quality of his accents in Dutch and Catalan dazzle people from the Netherlands and Spain.

He also has been:

…a painter, a bouncer, a punk rock roadie and a Kombucha delivery man.

Here is the full profile of Vaughn Smith. And here on YouTube. So what should I ask him?

Friday assorted links

1. Umbrex presents Tyler Cowen on Talent.

3. The guys behind the Turkish drones (New Yorker).

5. Catherine Rampell on the inflation conspiracy theory. #TheGreatForgetting