Results for “corporate profits” 98 found

My Fall Industrial Organization reading list

This is only part one for the class, do not panic over whatever you think might be completely left out. That said, suggested additions are welcome, here goes:

Competition

Bresnahan, Timothy F. “Competition and Collusion in the American Automobile Industry: the 1955 Price War,” Journal of Industrial Economics, 1987, 35(4), 457-82.

Bresnahan, Timothy and Reiss, Peter C. “Entry and Competition in Concentrated Markets,” Journal of Political Economy, (1991), 99(5), 977-1009.

Asker, John, “A Study of the Internal Organization of a Bidding Cartel,” American Economic Review, (June 2010), 724-762.

Whinston, Michael D., “Antitrust Policy Toward Horizontal Mergers,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol.III, chapter 36, see also chapter 35 by John Sutton.

“Benefits of Competition and Indicators of Market Power,” Council of Economic Advisors, April 2016.

Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout, “The Rise of Market Power and its Macroeconomic Implications,” http://www.janeeckhout.com/wp-content/uploads/RMP.pdf. My comment on it is here: https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2017/08/rise-market-power.html

Me on intangible capital, https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2017/09/intangible-investment-monopoly-profits.html.

Traina, James. “Is Aggregate Market Power Increasing?: Production Trends Using Financial Statements,” https://research.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/workingpapers/17isaggregatemarketpowerincreasing.pdf

Shapiro, Carl. “Antitrust in a Time of Populism.” UC Berkeley, working draft from 24 October 2017, forthcoming in International Journal of Industrial Organization.

Klein, Benjamin and Leffler, Keith. “The Role of Market Forces in Assuring Contractual Performance.” Journal of Political Economy 89 (1981): 615-641.

Breit, William. “Resale Price Maintenance: What do Economists Know and When Did They Know It?” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (1991).

Bogdan Genchev, and Julie Holland Mortimer. “Empirical Evidence on Conditional Pricing Practices.” NBER working paper 22313, June 2016.

Sproul, Michael. “Antitrust and Prices.” Journal of Political Economy (August 1993): 741-754.

McCutcheon, Barbara. “Do Meetings in Smoke-Filled Rooms Facilitate Collusion?” Journal of Political Economy (April 1997): 336-350.

Crandall, Robert and Winston, Clifford, “Does Antitrust Improve Consumer Welfare?: Assessing the Evidence,” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 2003), 3-26, available at http://www.brookings.org/views/articles/2003crandallwinston.htm.

FTC, Bureau of Competition, website, http://www.ftc.gov/bc/index.shtml., an optional browse, perhaps read about some current cases and also read the merger guidelines.

Parente, Stephen L. and Prescott, Edward. “Monopoly Rights: A Barrier to Riches.” American Economic Review 89, 5 (December 1999): 1216-1233.

Demsetz, Harold. “Why Regulate Utilities?” Journal of Law and Economics (April 1968): 347-359.

Armstrong, Mark and Sappington, David, “Recent Developments in the Theory of Regulation,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, chapter 27, also on-line.

Shleifer, Andrei. “State vs. Private Ownership.” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 1998): 133-151.

Xavier Gabaix and David Laibson, “Shrouded Attributes, Consumer Myopia, and Information Suppression in Competitive Markets,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=728545.

Strictly optional most of you shouldn’t read this: Ariel Pakes and dynamic computational approaches to modeling oligopoly: http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/pakes/files/Pakes-Fershtman-8-2010.pdf

http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/pakes/files/handbookIO9.pdf

Economics of Tech

Farrell, Joseph and Klemperer, Paul, “Coordination and Lock-In: Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol.III, chapter 31, also on-line.

Weyl, E. Glenn. “A Price Theory of Multi-Sided Platforms.” American Economic Review, September 2010, 100, 4, 1642-1672.

Tech companies as platforms, Tyler Cowen chapter, to be distributed.

Gompers, Paul and Lerner, Josh. “The Venture Capital Revolution.” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Spring 2001): 145-168.

Paul Graham, essays, http://www.paulgraham.com/articles.html, and on Google itself, http://www.slate.com/blogs/blogs/thewrongstuff/archive/2010/08/03/error-message-google-research-director-peter-norvig-on-being-wrong.aspx

Acemoglu, Daron and Autor, David, “Skills, Tasks, and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings,” http://econ-www.mit.edu/files/5607

Robert J. Gordon and Ian Dew-Becker, “Unresolved Issues in the Rise of American Inequality,”http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~idew/papers/BPEA_final_ineq.pdf

Song, Jae, David J. Price, Fatih Guvenen, and Nicholas Bloom. “Firming Up Inequality,” CEP discussion Paper no. 1354, May 2015.

Andrews, Dan, Chiara Criscuolo and Peter N. Gal. “Frontier firms, Technology Diffusion and Public Policy: Micro Evidence from OECD Countries.” OECD working paper, 2015.

Mueller, Holger M., Paige Ouimet, and Elena Simintzi. “Wage Inequality and Firm Growth.” Centre for Economic Policy Research, working paper 2015.

Readings on blockchain governance, to be distributed.

Haltiwanger, John, Ian Hathaway, and Javier Miranda. “Declining Business Dynamism in the U.S. High-Technology Sector.” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, February 2014.

Organization and capital structure

Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson on the firm, if you haven’t already read them, but limited doses should suffice.

Gibbons, Robert, “Four Formal(izable) Theories of the Firm,” on-line at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=596864.

Van den Steen, Eric, “Interpersonal Authority in a Theory of the Firm,” American Economic Review, 2010, 100:1, 466-490.

Lazear, Edward P. “Leadership: A Personnel Economics Approach,” NBER Working Paper 15918, 2010.

Oyer, Paul and Schaefer, Scott, “Personnel Economics: Hiring and Incentives,” NBER Working Paper 15977, 2010.

Tyler Cowen chapter on CEO pay, to be distributed.

Cowen, Tyler, Google lecture on prizes, on YouTube.

Ben-David, Itzhak, and John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey, “Managerial Miscalibration,” NBER working paper 16215, July 2010.

Glenn Ellison, “Bounded rationality in Industrial Organization,” http://cemmap.ifs.org.uk/papers/vol2_chap5.pdf

Miller, Merton, and commentators. “The Modigliani-Miller Propositions After Thirty Years,” and comments, Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 1988): 99-158.

Myers, Stewart. “Capital Structure.” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Spring 2001): 81-102.

Hansemann, Henry. “The Role of Non-Profit Enterprise.” Yale Law Journal (1980): 835-901.

Kotchen, Matthew J. and Moon, Jon Jungbien, “Corporate Social Responsibility for Irresponsibility,” NBER working paper 17254, July 2011.

Strictly optional but recommended for the serious: Ponder reading some books on competitive strategy, for MBA students. Here is one list of recommendations: http://www.linkedin.com/answers/product-management/positioning/PRM_PST/20259-135826

Production

American Economic Review Symposium, May 2010, starts with “Why do Firms in Developing Countries Have Low Productivity?” runs pp.620-633.

Dani Rodrik, “A Surprising Convergence Result,” http://rodrik.typepad.com/dani_rodriks_weblog/2011/06/a-surprising-convergence-result.html, and his paper here http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/drodrik/Research%20papers/The%20Future%20of%20Economic%20Convergence%20rev2.pdf

Serguey Braguinsky, Lee G. Branstetter, and Andre Regateiro, “The Incredible Shrinking Portuguese Firm,” http://papers.nber.org/papers/w17265#fromrss.

Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, “Recent Advances in the Empirics of Organizational Economics,” http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp0970.pdf.

Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, the slides for “Americans do I.T. Better: US Multinationals and the Productivity Miracle,” http://www.people.hbs.edu/rsadun/ADITB/ADIBslides.pdf, the paper is here http://www.stanford.edu/~nbloom/ADIB.pdf but I recommend focusing on the slides.

Bloom, Nicholas, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen. “Management as a Technology?” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 22327, June 2016.

Syerson, Chad “What Determines Productivity?” Journal of Economic Literature, June 2011, XLIX, 2, 326-365.

David Lagakos, “Explaining Cross-Country Productivity Differences in Retail Trade,” Journal of Political Economy, April 2016, 124, 2, 1-49.

Casselman, Ben. “Corporate America Hasn’t Been Disrupted.” FiveThirtyEight, August 8, 2014.

Decker, Ryan and John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda. “Where Has all the Skewness Gone? The Decline in High-Growth (Young) Firms in the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 21776, December 2015.

Furman, Jason and Peter Orszag. “A Firm-Level Perspective on the Role of Rents in the Rise in Inequality.” October 16, 2015.

http://evansoltas.com/2016/05/07/pro-business-reform-pro-growth/

Furman, Jason. ”Business Investment in the United States: Facts, Explanations, Puzzles, and Policy.” Remarks delivered at the Progressive Policy Institute, September 30, 2015, on-line at https://m.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20150930_business_investment_in_the_united_states.pdf.

Scharfstein, David S. and Stein, Jeremy C. “Herd Behavior and Investment.” American Economic Review 80 (June 1990): 465-479.

Stein, Jeremy C. “Efficient Capital Markets, Inefficient Firms: A Model of Myopic Corporate Behavior.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 104 (November 1989): 655-670.

Sectors: finance, health care, education, others

Gorton, Gary B. “Slapped in the Face by the Invisible Hand: Banking and the Panic of 2007,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1401882, published on-line in 2009.

Erel, Isil, Nadault, Taylor D., and Stulz, Rene M., “Why Did U.S. Banks Invest in Highly-Rated Securitization Tranches?” NBER Working Paper 17269, August 2011.

Healy, Kieran. “The Persistence of the Old Regime.” Crooked Timber blog, August 6, 2014.

More to be added, depending on your interests.

Why are U.S. firms holding more cash?

Somehow I missed this 2014 paper when it came out:

This paper explores the hypothesis that the rise in intangible capital is a fundamental driver of the secular trend in US corporate cash holdings over the last decades. Using a new measure, we show that intangible capital is the most important firm-level determinant of corporate cash holdings. Our measure accounts for almost as much of the secular increase in cash since the 1980s as all other determinants together. We then develop a new dynamic dynamic model of corporate cash holdings with two types of productive assets, tangible and intangible capital. Since only tangible capital can be pledged as collateral, a shift toward greater reliance on intangible capital shrinks the debt capacity of firms and leads them to optimally hold more cash in order to preserve financial flexibility.

That is from Antonio Falato, Dalida Kadyrzhanova, and Jae W. Sim. Once again, it seems that intangible capital is one of the biggest underrated ideas in economics.

My Fall 2017 Ph.d Industrial Organization reading list

It is long, and thus below the fold…

- Competition

Einav, Lira and Levin, Jonathan, “Empirical Industrial Organization: A Progress Report,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, (Spring 2010), 145-162.

Bresnahan, Timothy F. “Competition and Collusion in the American Automobile Industry: the 1955 Price War,” Journal of Industrial Economics, 1987, 35(4), 457-82.

Asker, John, “A Study of the Internal Organization of a Bidding Cartel,” American Economic Review, (June 2010), 724-762.

Bresnahan, Timothy and Reiss, Peter C. “Entry and Competition in Concentrated Markets,” Journal of Political Economy, (1991), 99(5), 977-1009.

Whinston, Michael D., “Antitrust Policy Toward Horizontal Mergers,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol.III, chapter 36, see also chapter 35 by John Sutton.

“Benefits of Competition and Indicators of Market Power,” Council of Economic Advisors, April 2016.

Klein, Benjamin and Leffler, Keith. “The Role of Market Forces in Assuring Contractual Performance.” Journal of Political Economy 89 (1981): 615-641.

Bogdan Genchev, and Julie Holland Mortimer. “Empirical Evidence on Conditional Pricing Practices.” NBER working paper 22313, June 2016.

Sproul, Michael. “Antitrust and Prices.” Journal of Political Economy (August 1993): 741-754.

McCutcheon, Barbara. “Do Meetings in Smoke-Filled Rooms Facilitate Collusion?” Journal of Political Economy (April 1997): 336-350.

Crandall, Robert and Winston, Clifford, “Does Antitrust Improve Consumer Welfare?: Assessing the Evidence,” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 2003), 3-26, available at http://www.brookings.org/views/articles/2003crandallwinston.htm.

FTC, Bureau of Competition, website, http://www.ftc.gov/bc/index.shtml. Read about some current cases and also read the merger guidelines.

Parente, Stephen L. and Prescott, Edward. “Monopoly Rights: A Barrier to Riches.” American Economic Review 89, 5 (December 1999): 1216-1233.

Demsetz, Harold. “Why Regulate Utilities?” Journal of Law and Economics (April 1968): 347-359.

Armstrong, Mark and Sappington, David, “Recent Developments in the Theory of Regulation,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, chapter 27, also on-line.

Shleifer, Andrei. “State vs. Private Ownership.” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 1998): 133-151.

Farrell, Joseph and Klemperer, Paul, “Coordination and Lock-In: Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol.III, chapter 31, also on-line.

Xavier Gabaix and David Laibson, “Shrouded Attributes, Consumer Myopia, and Information Suppression in Competitive Markets,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=728545.

Strictly optional: Ariel Pakes and dynamic computational approaches to modeling oligopoly: http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/pakes/files/Pakes-Fershtman-8-2010.pdf

http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/pakes/files/handbookIO9.pdf

2. Organization

Gibbons, Robert, “Four Formal(izable) Theories of the Firm,” on-line at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=596864.

“Make Versus Buy in Trucking: Asset Ownership, Job Design, and Information,” by George P. Baker and Thomas N. Hubbard, American Economic Review, (June 2003), 551-572.

Van den Steen, Eric, “Interpersonal Authority in a Theory of the Firm,” American Economic Review, 2010, 100:1, 466-490.

Miller, Merton, and commentators. “The Modigliani-Miller Propositions After Thirty Years,” and comments, Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 1988): 99-158.

Myers, Stewart. “Capital Structure.” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Spring 2001): 81-102.

Hansemann, Henry. “The Role of Non-Profit Enterprise.” Yale Law Journal (1980): 835-901.

Optional: Charness, Gary and Kuhn, Peter J. “Lab Labor: What Can Labor Economists Learn From the Lab?” NBER Working Paper, 15913, 2010, Lazear, Edward P. “Leadership: A Personnel Economics Approach,” NBER Working Paper 15918, 2010, Oyer, Paul and Schaefer, Scott, “Personnel Economics: Hiring and Incentives,” NBER Working Paper 15977, 2010.

Cowen, Tyler, Google lecture on prizes, on YouTube.

3. Production

American Economic Review Symposium, May 2010, starts with “Why do Firms in Developing Countries Have Low Productivity?” runs pp.620-633.

Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, “Recent Advances in the Empirics of Organizational Economics,” http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp0970.pdf.

Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, the slides for “Americans do I.T. Better: US Multinationals and the Productivity Miracle,” http://www.people.hbs.edu/rsadun/ADITB/ADIBslides.pdf, the paper is here http://www.stanford.edu/~nbloom/ADIB.pdf but I recommend focusing on the slides.

Bloom, Nicholas, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen. “Management as a Technology?” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 22327, June 2016.

Syerson, Chad “What Determines Productivity?” Journal of Economic Literature, June 2011, XLIX, 2, 326-365.

Diego Restuccia and Richard Rogerson, “The Causes and Costs of Misallocation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Summer 2017, 31, 3, 151-174.

Dani Rodrik, “A Surprising Convergence Result,” http://rodrik.typepad.com/dani_rodriks_weblog/2011/06/a-surprising-convergence-result.html, and his paper here http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/drodrik/Research%20papers/The%20Future%20of%20Economic%20Convergence%20rev2.pdf

Serguey Braguinsky, Lee G. Branstetter, and Andre Regateiro, “The Incredible Shrinking Portuguese Firm,” http://papers.nber.org/papers/w17265#fromrss.

David Lagakos, “Explaining Cross-Country Productivity Differences in Retail Trade,” Journal of Political Economy, April 2016, 124, 2, 1-49.

Casselman, Ben. “Corporate America Hasn’t Been Disrupted.” FiveThirtyEight, August 8, 2014.

Decker, Ryan and John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda. “Where Has all the Skewness Gone? The Decline in High-Growth (Young) Firms in the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 21776, December 2015. NB: This paper and the three that follow have some repetition, so read them selectively rather than exhaustively.

Decker, Ryan and John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda. “The Secular Business Dynamism in the U.S.” Working paper, June 2014.

Haltiwanger, John, Ian Hathaway, and Javier Miranda. “Declining Business Dynamism in the U.S. High-Technology Sector.” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, February 2014.

Haltiwanger, John, Ron Jarmin and Javier Miranda. Where Have All the Young Firms Gone? Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, May 2012.

Song, Jae, David J. Price, Fatih Guvenen, and Nicholas Bloom. “Firming Up Inequality,” CEP discussion Paper no. 1354, May 2015.

Andrews, Dan, Chiara Criscuolo and Peter N. Gal. “Frontier firms, Technology Diffusion and Public Policy: Micro Evidence from OECD Countries.” OECD working paper, 2015.

Furman, Jason and Peter Orszag. “A Firm-Level Perspective on the Role of Rents in the Rise in Inequality.” October 16, 2015.

Mueller, Holger M., Paige Ouimet, and Elena Simintzi. “Wage Inequality and Firm Growth.” Centre for Economic Policy Research, working paper 2015.

http://evansoltas.com/2016/05/07/pro-business-reform-pro-growth/

Furman, Jason. ”Business Investment in the United States: Facts, Explanations, Puzzles, and Policy.” Remarks delivered at the Progressive Policy Institute, September 30, 2015, on-line at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20150930_business_investment_in_us_facts_explanations_puzzles_policies_slides.pdf

Scharfstein, David S. and Stein, Jeremy C. “Herd Behavior and Investment.” American Economic Review 80 (June 1990): 465-479.

Chen, Peter, Loukas Karabarbounis, and Brent Neiman. “The Global Rise of Corporate Saving.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 23133, February 2017.

4. Incentives

Edmans, Adam, Xavier Gabaix, and Dirk Jenter, “Executive Compensation: A Survey of Theory and Evidence,” NBER Working Paper 23596, July 2017.

Kaplan, Steven N. “Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance in the U.S.: Perceptions, Facts and Challenges.” Working paper, July 2012.

Robert J. Gordon and Ian Dew-Becker, “Unresolved Issues in the Rise of American Inequality,” http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~idew/papers/BPEA_final_ineq.pdf

Stein, Jeremy C. “Efficient Capital Markets, Inefficient Firms: A Model of Myopic Corporate Behavior.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 104 (November 1989): 655-670.

https://marginalrevolution.com/?s=short-termism

Ben-David, Itzhak, and John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey, “Managerial Miscalibration,” NBER working paper 16215, July 2010.

5. Sectors: finance, health care, tech, others

Gorton, Gary B. “Slapped in the Face by the Invisible Hand: Banking and the Panic of 2007,” http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1401882, published on-line in 2009.

Erel, Isil, Nadault, Taylor D., and Stulz, Rene M., “Why Did U.S. Banks Invest in Highly-Rated Securitization Tranches?” NBER Working Paper 17269, August 2011.

Philippon, Thomas. “Has the U.S. Finance Industry Become Less Efficient? On the Theory and Measurement of Financial Intermediation.” Working paper, September 2014.

Gompers, Paul and Lerner, Josh. “The Venture Capital Revolution.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 2001, 145-168.

Paul Graham, essays, http://www.paulgraham.com/articles.html.

Optional: consider subscribing to Ben Thompson’s Stratechery, periodic emails on the tech industry, note it is expensive.

Friedman, Milton. “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.” The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 1970.

Healy, Kieran. “The Persistence of the Old Regime.” Crooked Timber blog, August 6, 2014.

More to be added, depending on your interests.

Larry Summers on the new Republican tax plan

He summarizes the plan as follows:

The central concept put forward by Mr Ryan, which appears to have the support of Mr Trump, is to turn corporate income tax from a tax on the return to capital into a tax only on extraordinary profits. This would be done by taxing corporate cash flows. In addition to the major reduction of the overall rate, the system would change in three fundamental ways. First, all investment outlays can be written off in the year they occur rather than over time. Second, interest payments to bondholders, banks and other creditors will no longer be deductible. Third, companies will be able to exclude receipts from exports in calculating their taxable income and will not be permitted to deduct payments to foreign suppliers or affiliates from income.

I found this to be the paragraph I had not seen elsewhere:

Second, the tax change will capriciously redistribute income, increase uncertainty and place punitive burdens on some sectors. Think of a retailer who imports goods from abroad for 60 cents, incurs 30 cents in labour and interest costs, and then earns a 5 cent margin. With a 20 per cent tax, and no ability to deduct import or interest costs, the taxes will substantially exceed 100 per cent of profits even if there is some offset from a stronger dollar. Businesses that invest heavily, hire extensively and export a large part of their product will have negative taxable income on a chronic basis. It is hard to imagine that the political process will allow annual multibillion-dollar refunds, so they too may be victimised. Then there are the still unresolved questions of what the rules will be on interest deductibility for banks and of the treatment of businesses organised as partnerships that do not pay corporate taxes.

Here is the FT link, probably gated for most of you, WaPo link here. Summers also argues the plan will worsen inequality, strengthen the dollar (possibly leading to EM crises), lead to a trade war, and erode the long-term tax base.

Just to refresh your memories here is Jared Bernstein on the same plan (mixed but mostly negative), and Martin Feldstein (positive).

Floating exchange rates and tariffs

Not long ago I mentioned that a joint export subsidy and import tax would be offset by an appreciation of the real exchange rate. It’s worth pondering whether such results are the same for fixed and floating rates.

In the simplest model, the choice of exchange rate doesn’t matter. The real terms of trade adjust to the subsidy/tax mix under either regime, with the same final equilibrium.

That said, you might think that goods prices in international trade are nominally sticky in a way that exchange rates are not. Indeed you would be right, noting we don’t have a completely clear idea how much delivery lags and service quality changes sub in for some of (not all) the real price movements.

But there is a subtler difference as well. In a world of floating exchange rates, terms of trade move around more, in real terms, than if exchange rates were fixed. Call it noise, bubbles, or whatever, but sometimes nominal exchange rates have a “mind of their own,” and real exchange rates move much of the way with them.

For that reason, companies that engage in international trade have to be more robust to possible “taxes” — which include unfavorable exchange rate movements — than under the fixed rate regime. As a quick shorthand, I would say those companies need to have more market power to put up with the exchange rate volatility, though you can give the required corporate properties a few different twists, typically involving fixed costs, sunk costs, option values and the like rather than just market power in its simplest conception (it’s complicated.)

In other words, floating exchange rates, especially when there is a historical experience of ongoing real exchange rate volatility, will mean companies are more tariff-robust.

This is one reason why the Trump protectionist talk, while it is 110% bad, and bad for American foreign policy as well, and bad for uncertainty, and bad bad bad bad bad, and sometimes connected to bad bad bad people as well (did I say bad? It’s BAD!), won’t quite have the negative economic impact that many people think.

Think back to the mid-80s, when the USD went from 3.45 Deutschmarks to 1.7 Deutschmarks in what, less than two years’ time? That was the equivalent of a huge tax on Mercedes-Benz as an exporting firm. Did Mercedes like that? No. Did they manage? Well, mostly, sort of. Of course they had a fair amount of market power at the time, they would have less today.

A five percent tariff, relative to the built-in adjustments possible in light of changes in floating exchange rates, is for the most part manageable, at least on narrow economic grounds. Much of that five percent ends up as a tax on the monopoly profits of exporters. You can google and read up on “exchange rate pass-through.”

You will note that some of this argument draws on earlier research by Paul Krugman, though I am not suggesting he necessarily agrees with my application or interpretation; here are his recent remarks.

The foreign policy and presidential signaling and uncertainty-related issues, not the narrow economics, are still the main problem with a five or ten percent trade tax, and they are reason not to go down this route. But it is worth being clear on the economics. The oversimplified statement of the neglected insight here is “floating exchange movements tax trade all the time.”

Bengt Holmström, Nobel Laureate

Again, I’ll be refreshing this post throughout the morning, keep on hitting refresh. Here is Bengt Holmström’s home page, which includes a CV, short biography, and links to research papers. Here is his Wikipedia page. He has taught for a long time at MIT, was born in Finland, and is one of the most famous and influential economists in the field of contracts and industrial organization. Here is the Swedish summary. Here is a video explanation. This is a nice short bio of how he was influenced by his private sector experience, recommended, not just the usual take on him.

One key question he has considered is when incentives should be high-powered or when they should be more blunt. It is now well known that you get what you pay for; see Alex’s excellent summary on this and related points.

His most famous paper is his 1979 “Moral Hazard and Observability.” What are the optimal sharing rules when the principal can observe outcomes but not efforts or inputs? And how might those sharing rules lead to a less than optimal result? This is probably the most elegant and most influential statement of how direct incentives and insurance value in a contract can conflict and hinder efficiency. A simple example — what about deductibles in a health insurance contract? Yes, they do encourage the customer to internalize the value of staying in better health. But they also limit the insurance value of a contract. That a first best outcome will not be created in this situation was part of what Holmstrom showed, and he showed it in a relatively tractable way.

If you are thinking about CEO compensation, you might turn to the work of Holmström, the Swedes have a good summary of this paper and point:

…an optimal contract should link payment to all outcomes that can potentially provide information about actions that have been taken. This informativeness principle does not merely say that payments should depend on outcomes that can be affected by agents. For example, suppose the agent is a manager whose actions influence her own firm’s share price, but not share prices of other firms. Does that mean that the manager’s pay should depend only on her firm’s share price? The answer is no. Since share prices reflect other factors in the economy – outside the manager’s control – simply linking compensation to the firm’s share price will reward the manager for good luck and punish her for bad luck. It is better to link the manager’s pay to her firm’s share price relative to those of other, similar firms (such as those in the same industry).

That is again a result about how incentives and insurance interact. When do you pay based on perceived effort, and when on the basis of observed outcomes, such as profits or share price? Holmström has been the number one theorist in helping to address issues of this kind.

“Moral Hazard in Teams,”1982, is a very famous and influential paper, here is the working paper version. Holmström showed that the optimal incentive scheme has to consider time consistency. Sometimes good incentive schemes impose penalties on the workers/agents to get them to work harder. But let’s say you had a worker-owned and worker-run firm. If the workers fail, will the workers/owner impose punishments on themselves? Maybe not. Thus in a fairly general class of situations you need an outside residual claimant to impose and receive the penalty. This is Holmström trying to justify one feature of the capitalist system against socialists and Marxists.

A Fine Theorem has an excellent post on his work.

“Managerial Incentive Problems: A Dynamic Perspective” is another goodie, this one from 1999. The key point is that repeated interactions, for instance with a manager, can make incentive problems worse rather than better. The more the shareholders monitor a manager, for instance, and the more that is over a longer period of time, perhaps the manager has a greater incentive to manipulate signals of value. When are career incentives beneficial or harmful? This paper is the starting point in thinking through this problem. Here is one of the possible traps: if a worker fully reveals his or her quality to the boss, the boss will use that information to capture more surplus from the worker. So many workers don’t let on just how talented they are, so they can slack more, rather than being caught up in the dragnet of a ‘super-efficient” incentives scheme. I have long found this to be a very important paper, it is probably my favorite by Holmström.

This 1994 investigation, based on personnel data from within firms, is actually way ahead of its time in terms of empirical methods. It is certainly known but he never received full credit for it.

Holmström and Hart together have a very nice piece surveying the theory of contracts and theories of the firm. With John Roberts, he has a very nice (and highly readable!) survey of economic work on theories of the boundary of the firm, recommended on the field more generally. Not his most famous piece, but if you are looking in the applied direction, here is his survey piece with Steven Kaplan on mergers.

With Jean Tirole has has a 1997 paper “Financial Intermediation, Loanable Funds, and the Real Sector.” This was an important precursor of the later point about how collateral constraints really can matter. Firms and banks should be well-capitalized! This piece was significantly influenced by the Nordic financial crises of the 1990s and it was prescient regarding later events in the United States and elsewhere.

His liquidity-based asset pricing model, with Jean Tirole, did not in its published form “take off” in the world of finance, but it is an excellent and important piece, worth revisiting as part of the puzzle of why the world has so many super-low interest rates today.

Holmström has since written much more about banking and agency problems. His very latest piece is on banks as secret keepers, and it tries to model and explain the fundamental nature of banking and its fixed value liabilities. Here is his piece on why financial panics are so likely to involve debt. With Jean Tirole, he wrote a well-known paper on why government supply of liquidity services sometimes may be justified.

Here is his 2003 survey paper, with Steven Kaplan, on what is right and wrong in U.S. corporate governance. It is a more applied side than what you often see from him. The piece claims that, even in light of the scandals of that time, American corporate governance is not broken and will probably become better yet, though it could stand some improvement, including on the regulatory side. Overall I view his co-authorships with Kaplan as suggesting that his overall stance toward corporations is more influenced by Chicago-style thinking than is oftetn the case at MIT. Read his defense of asset securitization for instance.

Congratulations to Bengt Holmström!

Oliver Hart, Nobel Laureate

Here is Hart’s most famous piece, with Sandy Grossman, 1986, “The Costs and Benefits of Ownership.” Think of it as an extension of Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson, also two Nobel Laureates (hey, that’s a lot of prizes for one topic area…)

Why does one party ever purchase residual rights in the assets of another party? Say for instance there is a factory firm and a coal mining firm. The coal can be treated in a particular way to be more suitable for use in the factory. If the factory firm buys out the coal mining company, the incentives for coal treatment differ, that is the key insight behind this model. You can think of this as a very important modification of the Coase Theorem. It does matter who owns the asset. Why? If the coal mining company owns the coal, it has one set of incentives to make ex ante improvements in the values of those assets; if the factory firm owns the coal mine, it has another set of incentives. Part of the work in this paper is done by a bargaining axiom — if you own an asset outright, you keep a greater share of the proceeds from improving the value of that asset. Ownership should thus migrate to those parties who have the greatest ability to improve value.

And that is a very fundamental improvement on the Coase theorem, which suggests ownership won’t matter when there is ex post contractibility. This paper showed that for ownership not to matter there must also be ex ante contractibility about value-improving investments at earlier stages in the game, an unlikely assumption to hold.

This is a tricky paper to master. It has all kinds of assumptions built in about ownership, control, and residual claimancy, which do not move together in simple ways. Eventually Hart (working with others) cleaned up the assumptions and produced a more transparent model of this process. This paper is a — I should say the — starting point for thinking about mergers, vertical integration, and other questions of corporate ownership and contract and control. Bengt Holmström of all people wrote a very nice appreciation of the paper.

What about Grossman, I hear you wondering? I would have guessed he would have shared in the Prize, as he has other seminal papers about information and much of Hart’s key work is co-authored with him. On the bright side for him, he has made hundreds of millions of dollars running a hedge fund.

Hart is a true gentleman and he has a very nice British accent. He is very highly respected by his peers. Here is his Wikipedia page. Here is his home page, he is now at Harvard but spent part of his career at MIT. Here is his vita. Here is Hart on Google Scholar. Here is the Nobel survey essay from Sweden. Here is a video explanation.

His second best known piece is “Property Rights and the Nature of the Firm,” with John Moore, 1990. This is again a model and series of parables about ownership and the allocation of rights, but with some twists on the earlier Grossman and Hart piece. The key point is to not allow inessential agents to achieve blocking power of value creation. The authors tell a story about a venture with a tycoon, a boat owner, and a chef, all of whom might organize a voyage together. The tycoon and the boat owner are essential, so one of them should own the boat, and then they can split most of the surplus from the voyage and pay the chef his or her marginal product. Value creation then proceeds. Alternatively, if the chef owns the boat, he has potential blocking power and the surplus has to be split three ways. That may result in some loss of value, due to a tougher bargaining problem, higher transactions costs, and a chance there won’t be enough surplus to cover the most significant investments. Parties who create a lot of value should own things is the central message here, and this is another key paper for thinking about contracts, ownership, and what kind of business arrangements induce investment in idiosyncratic assets, yet another follow-up on the work of previous Laureates Coase and also Oliver Williamson.

In case you hadn’t figured it out by now, Oliver Hart is basically a theorist in his major lines of research.

Another famous paper by Grossman and Hart is “Takeover Bids, the Free Rider Problem, and the Theory of the Corporation.” One of Alex’s most interesting papers is an extension of this work, so I suspect he’ll be covering it in detail. In a nutshell, this model helps explain why a lot of value-maximizing takeover don’t happen, or why it is hard to buy up a whole city block and renovate it. Let’s for instance a corporation currently is valued at $80 a share, and a raider has a good plan to make the company worth $100 a share. The raider then comes along and offers you, a shareholder, $90 for each of your shares. Will you sell? Well, it depends what you think the other shareholders will do. But you might not sell, instead seeking to hold on for the ride. If others sell, you can get $100 in value instead of $90. But if everyone feels this way, then no one sells and the bid fails. Then you might sell at $90 after all, but then no one will sell after all…and so on. A tough problem, but this is a very important piece in understanding the limitations of various kinds of takeovers. Right now my security device won’t let me link to the paper but try googling the title.

Hart’s 1983 paper with Sandy Grossman was at the time a breakthrough and highly rigorous means of modeling the principal-agent problem. It is in Econometrica and quite hard for many people to read. Economists had been modeling principal-agent problems through the notion of a participation constraint. Have the contract give incentives, subject to the proviso that it is still worthwhile for the agents to be involved in the trades. But Mirrlees had pointed out this can give misleading results when there is not automatically a unique solution to the problem at hand. Grossman and Hart reconceptualized the math into a convex programming problem. Theorists love the paper, and it was highly influential when it came out.

Here is Hart and Moore on incomplete contracts and renegotiation. This paper is connected to the Nobel Prize for Jean Tirole two years ago. How can you write a contract so a) parties will make the appropriate relationship-specific investments, and b) it doesn’t have to be renegotiated all of the time? Again, Hart’s work is obsessed with this idea of value maximization within corporate endeavors and possible obstacles to such value maximization.

By the way, here is Hart, with Shleifer and Vishny, on why the private sector probably should not be allowed to own and run prisons. The incentive to cut costs is too strong! Government ownership will instead, in their view, create more value maximization because the government won’t have the same profit incentive to skimp on quality along various margins. This paper has been highly influential in recent debates over private ownership of prisons, which recently was countermanded at the federal level at least. You also probably wouldn’t want Air Force One owned by the private sector, though you do want it to be designed and produced by the private sector. This paper helped produce a framework for understanding the reasons why.

Hart’s 1979 piece on shareholder unanimity asks the important theory question of whether all shareholders will desire that firms maximize profits if markets are incomplete and some firm shares also serves secondary “insurance” purposes of helping protect against adverse states of the world. For instance, say there is no insurance market in wheat. You might use the shares of a wheat-producing firm for that purpose, and desire, for insurance purposes that the value of the firm covary with the value of wheat in ways that differ from simple firm profit-maximization. The upshot of this literature is that firm profit maximization is not as simple or as self-evident an assumption as people used to think.

By the way, here are the two Laureates together, on “A Theory of Firm Scope.” Here is their long, joint survey on theory of contracts.

Congratulations to Oliver Hart!

Peter Navarro outlines the Trump economic plan

To score the benefits of eliminating trade deficit drag, we don’t need any complex computer model. We simply add up most (if not all) of the tax revenues and capital expenditures that would be gained if the trade deficit were eliminated. We have modeled only the impacts of implicit profits and wages, not any other economic aspect of the increased activity.

Trump proposes eliminating America’s $500 billion trade deficit through a combination of increased exports and reduced imports. Again assuming labor is 44 percent of GDP, eliminating the deficit would result in $220 billion of additional wages. This additional wage income would be taxed at an effective rate of 28 percent (including trust taxes), yielding additional tax revenues of $61.6 billion.

In addition, businesses would earn at least a 15% profit margin on the $500 billion of incremental revenues, and this translates into pretax profits of $75 billion. Applying Trump’s 15% corporate tax rate, this results in an additional $11.25 billion of taxes.

Emphasis is added by this author.

Here is the full document (pdf). Here is my earlier profile of Peter Navarro. For the pointer I thank the excellent Binyamin Appelbaum.

Addendum: Scott Sumner comments.

Regulation and Rents

Here’s James Bessen writing in the Harvard Business Review:

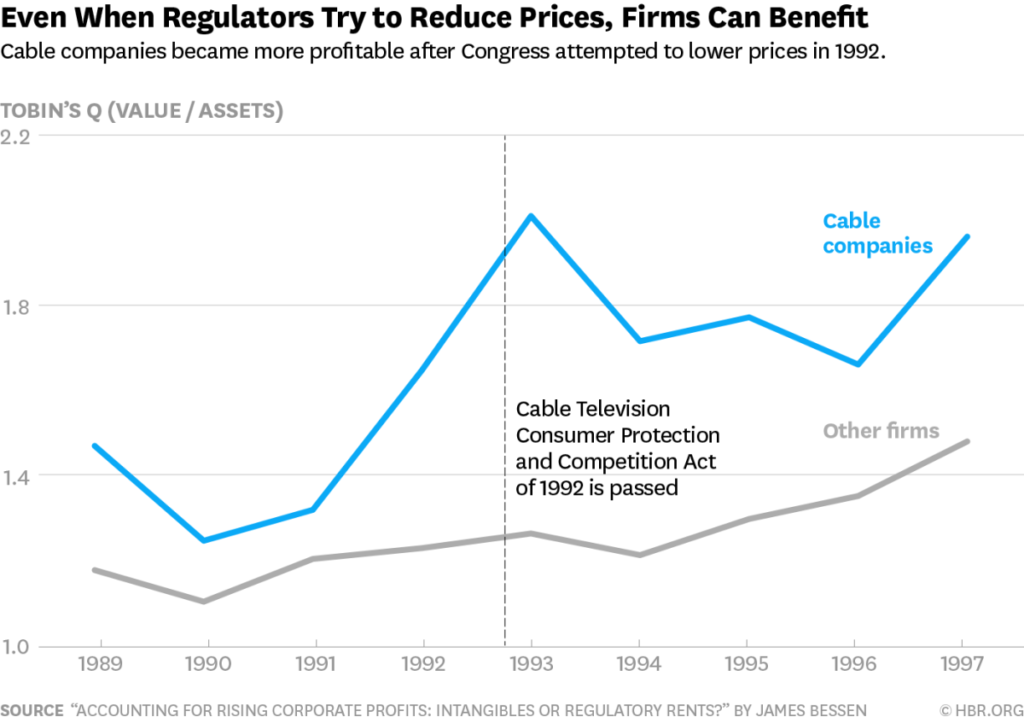

…in 1992 Congress passed the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act in response to high cable TV rates. Regulators expected cable prices to fall by 10%. Instead, however, cable companies changed their programming bundles, prices did not fall, and corporate valuations increased. The chart below shows that the aggregate market value of cable companies relative to assets (Tobin’s Q) rose following the Act, compared to valuations of other firms.

Regulation doesn’t seem to have reduced profits in the cable industry and may have increased profits. Is there a general lesson here? In a new paper, Bessen finds that the answer is yes:

The pattern around the 1992 Cable Act is representative: I find that firms experiencing major regulatory change see their valuations rise 12% compared to closely matched control groups. Smaller regulatory changes are also associated with a subsequent rise in firm market values and profits.

This research supports the view that political rent seeking is responsible for a significant portion of the rise in profits. Firms influence the legislative and regulatory process and they engage in a wide range of activity to profit from regulatory changes, with significant success. Without further research, we cannot say for sure whether this activity is making the economy less dynamic and more unequal, but the magnitude of this effect certainly heightens those concerns.

Addendum: Reed Hundt, chairman of the FCC from 1993 to 1997, discusses cable TV regulation during this period in the comments.

Why Germany doesn’t like negative interest rates

The business models of German financial institutions depend critically on the presence of positive nominal interest rates. The International Monetary Fund noted in its latest Financial Stability Report that the pre-tax profits of German and Portuguese banks are most affected by negative rates.

German life insurers are also vulnerable. They have to guarantee a minimum rate of return, which is now 1.25 per cent a year. This is hard to do when the yield of the 10-year German government bond is only 0.13 per cent. Germany and Sweden are the two EU countries where life insurers face the biggest gap between market rates and guaranteed rates. To achieve the promised returns, the insurers have to take on more risk, for example by buying corporate bonds or tranches of complex financial products. If, or rather when, the next financial crisis arrives and triggers a change in the valuation of these assets, we may find that sections of the German financial sector are insolvent.

Of the German banks, the Sparkassen and the mutual savings banks are most affected. They are classic savings and loans outlets in that they lend locally and fund themselves through savings. Credit demand is more or less fixed. So when savings exceed loans, as they now do in Germany, the banks deposit their surplus with the ECB at negative rates — known as “penalty rates” in Germany. They cannot offset the losses by cutting interest rates on savings accounts because of the zero lower bound. Savers would switch from accounts to cash in safe deposit boxes.

That is from the always superb Wolfgang Münchnau at the FT. Regulatory and federalistic issues are another and underdiscussed reason why the eurozone is not an optimal currency area.

China fact of the day

Given that non-financial total corporate debt is estimated by McKinsey to amount to $12.5tn, Chinese companies are paying on a nominal basis some $812bn in interest payments each year. In real terms, this amounts to $1.35tn. This is not only significantly more than China’s projected total industrial profits this year; it is slightly bigger than the size of a large emerging economy such as Mexico.

The entire FT discussion is here.

Adjudicating the Krugman-Bernanke debate on secular stagnation

Here is Krugman’s long and complex post, do read it carefully. Here are a few points:

1. Bernanke said that non-secular stagnation in other countries might cause capital outflows and thus exchange rate depreciations in the potentially ss (secular stagnation) countries, thereby boosting their exports and demand.

2. Krugman argues in return that those real interest rate differentials will be offset by expected exchange rate appreciation, so the capital outflows won’t be so profitable. Why switch funds from a stagnating Europe to a non-stagnating India, if expected euro appreciation will wipe out potential profits in India from the point of view of an investor in Europe?

3. I think that is the wrong comparison of interest rates and the wrong metric of expected currency appreciation.

4. Rather than looking at real interest rate differentials, take the market’s implied prediction for the euro to be the forward-futures exchange rates. These futures rates match the differences in nominal rates on each currency across the relevant time horizons. Those equilibrium relationships hold true with or without secular stagnation, whether in one country or in “n” countries, and from those relationships you cannot derive the claim that expected currency movements offset cross-border differences in real rates of return.

4b. (It is the nominal rate here because, from the point of view of a European investor, your final real return in terms of your own unit of account depends on a combination of the nominal rate abroad, combined with expected future currency conversion rates. Got that?)

5. In that setting, rates of return in non-ss countries still will drive capital flows toward those countries (and an exchange rate depreciation, and thus higher exports, for the origin country, in this case the eurozone.)

6. The best way to speak of the non-ss countries, for international economics, is that their corporate sectors offer nominal expected rates of return which are relatively high, compared to their nominal government bond rates. Once you see this as the correct terminology, it is obvious that capital still will flow outwards to the non-ss countries, even with expected exchange rate movements. The excess profits are there, capital flows out, the euro weakens or appreciates less strongly, and eurozone exports are stimulated, as Bernanke had analyzed.

7. Theory aside, some of the empirics suggest exchange rates often are close to a random walk (pdf), as opposed to being predicted by nominal interest rate differentials. This still supports the Bernanke hypothesis.

8. Yes, I am familiar with the Frankel (1979) strand of the literature on how real interest differentials can forecast currency changes, but it is actually a theoretical puzzle that domestically measured real interest rates (sometimes) have had this explanatory power. And most importantly in this literature high real rates of return tend to predict currency appreciation, not depreciation, so funds should flow all the more to the higher return venues. It is not a rigorous relationship in any case. And on top of that Mishkin (1984), among others, has shown such an equalization on the real interest rate, across borders, is rejected by the data.

9. So I agree with Bernanke. We should not think of real interest rate differentials as being washed out by expected currency movements. And then the flow of investment abroad can break the secular stagnation chain of reasoning.

10. Bernanke is not arguing that “currency movements and export boosts will set everything right.” I take him to be suggesting “if the problem were so fully one of the demand-side, currency movement and export boosts could set everything right.” But since it seems they can’t set everything right, we should infer it is not a problem of the demand side only. That is a subtle but important difference in argumentation.

11. Personally, I favor supply-side over demand-side analysis for the long run.

The 2014 Nobel Laureate in economics is Jean Tirole

A theory prize! A rigor prize! I would say it is about principal-agent theory and the increasing mathematization of formal propositions as a way of understanding economics. He has been a leading figure in formalizing propositions in many distinct areas of microeconomics, most of all industrial organization but also finance and financial regulation and behavioral economics and even some public choice too. He is a broader economist than many of his fans realize.

Tirole is a Frenchman, he teaches at Toulouse, and his key papers start in the 1980s. In industrial organization, you can think of him as extending the earlier work of Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson with regard to opportunism and recontracting, but applying more sophisticated and more mathematical forms of game theory. Tirole also has been a central figure in procurement theory and optimal contracts when there is asymmetric information about costs. The idea of mechanism design runs throughout his papers in many different guises. Many of his papers show “it’s complicated,” rather than presenting easily summarizable, intuitive solutions which make for good blog posts. That is one reason why his ideas do not show up so often in blogs and the popular press, but they nonetheless have been extremely influential in the economics profession. He has shown a remarkable breadth and depth over the course of the last thirty or so years.

His possible pick had been heralded for some numbers of years now, this award should not be considered a surprise at all. You will note that the Swedes mention Jean-Jacques Laffont, who died a decade ago, and who co-authored many of the key papers in this area with Tirole. Such a mention is considered a nod in the direction of implying that Laffont, had he lived, would have shared in the prize.

Here is Tirole’s home page. Here is Tirole on Wikipedia. Here is a short biography. Here is Tirole on scholar.google.com. Here is the press release. Here is background from the Swedes. Here is the 54-page document on why he won, one of the best places to start. Here is the Twitter commentary.

One idea of Tirole’s I use frequently has to do with renegotiability. Let’s say a regulator and a monopolist agree to a scheme of regulation and provision, creating some surplus for both parties. As time passes, will each side of that bargain stick with the original agreement? A simple example here is the defense contractor. After a procurement contract is written, sometimes the supplier has the incentive to conduct a hold-up, to report that costs are higher than expected, and to ask for more money in return for timely fulfillment of the contract. Of course this is a contract breach, but if no other supplier can step in and do the job, it may be optimal for the government to give in to these demands to some degree. The question then is: how should the contract best be designed in advance, so as to prevent this problem from popping up later on? Or should the renegotiation simply be allowed? Anyone wishing to tackle these questions likely would start with the papers of Tirole on this topic. For one thing, these papers help explain why a second-best optimal contract may offer some rents to agents and appear to give the agent “too good a deal.”

Some of his key papers focus on asymmetric information about costs. Say a firm knows its costs and the regulator can only guess. Ideally the regulator would likely to make the firm price at marginal cost, but the firm will pretend marginal cost is higher than it really is. The regulator and the firm thus play a game. Tirole figured out with rigor which principles govern how this game works and what a second-best regulatory solution might look like. With Laffont, here is his key paper in that area. David Baron made contributions to this area as well. Again, there is a potential argument for an “agent rent,” to limit the incentive of the agent to lie too much about costs, for fear of losing that rent if the cooperative relationship breaks down.

Tirole, writing sometimes with Rey, wrote some important papers on vertical agreements and how they can be used to extend market power, for instance when can buying up parts of a supply chain help extend monopoly power? His paper with Oliver Hart figures out some of the conditions under which vertical acquisitions can help foreclose a market. With Rey, Tirole surveys the literature on vertical relations and foreclosure.

This early 1984 paper, with Drew Fudenberg, laid out the conditions when firms should overinvest in capacity to deter competitive entry, or when firms should instead look “lean and mean” for entry deterrence. The underlying analysis has shaped many a business school discussion.

I am a fan of this 1996 paper on how we can think of firms as credible ways of carrying reputations in a collective sense. For instance the existence of a firm called “Google” transmits real information about the qualities of the people you deal with when you are transacting with members of the Google firm. This was an important addition to the usual Coasean vision of thinking of a firm in terms of economizing transaction costs.

He has written some key papers on financial intermediation, collateral, and the agency problems associated with lending, here is one well-cited paper by him and Holmstrom. Here is a non-gated version (pdf). A key argument is that a decline in the value of the collateral in a lending relationship can lower efficiency and also output, and this can help explain some features of business cycles. This 1997 paper was well ahead of its time and it remains one of Tirole’s most widely cited works. Arguably it is relevant for recent financial crises.

He has a 1994 book with Mathias Dewatripont on the prudential regulation of banks and how to apply the proper incentives to make sure banks do not take too much risk at public expense. Obviously this also has since become a much more important topic. How many of you know his 1996 paper with Rochet on “Interbank Lending and Systemic Risk“? They show the contradictions which can plague a “too big to fail” policy and the attempts of central banks to maintain a “creative ambiguity” about what kinds of bailouts will occur, using rigorous game theory of course.

With Rochet, he has a well-known paper on platform competition, laying out the basics of how these “two-sided” markets work. Think of internet or payment portals which must get both sides of the market on board. What are the efficiency properties of such markets and what are the game-theoretic issues? In this setting, how do for-profits compare to non-profits? Competition to monopoly? Rochet and Tirole laid out some of the basics here, here is their survey piece on the field as a whole. Alex’s post above has much more on these points, and Joshua Gans covers this area too, here is Vox.

In public choice economics, he and Laffont have an important paper on when regulatory capture is actually likely to occur. I have yet to see the insights of this paper incorporated into the rest of the literature adequately. His paper on the internal organization of government considers the relative appropriateness of high- vs. low-powered incentives as applied to government employees, among other matters. His 1999 paper with Mathias Dewatripont, “Advocates,” shows in game-theoretic terms why something like the Anglo-American system of competing lawyers might make sense as the best way of discovering information and adjudicating the truth. This paper shows how career concerns affect bureaucratic incentives and what is the optimal degree of specialization within a government bureaucracy.

He has thought very deeply about the nature of liquidity and what is the optimal degree of liquidity in a securities market. There can be some side benefits to illiquidity, namely that it forces parties to stay committed to an economic relationship. This must be weighed against the more obvious benefits of liquidity, which include having better benchmarks for measuring managerial performance, namely stock price (see this paper with Holmstrom). This kind of analysis can be applied to the question of whether the shares of a firm should stay privately traded or be put on a public exchange. This 1998 paper, with Holmstrom, is a key forerunner of the current view that the global economy does not have enough in the way of safe assets.

Here is his paper on vertical structure and collusion in bureaucracies (pdf). Here is his very useful survey article, with Holmstrom, on the theory of the firm.

His textbook on Industrial Organization is a model of clarity and remains a landmark in the field, even though it came out almost thirty years ago.

He has written a book on telecommunications regulation (with Laffont) although I have never read that material.

In finance he wrote this key 1985 paper, deriving the conditions under which you can have an asset bubble in a market with rational expectations. The problem of course is that the price of the asset tends to keep rising, relative to the size of the economy as a whole, and eventually it becomes impossible to keep on buying the asset. This has to mean an eventual crash, unless the growth rate of the economy exceeds the general rate of return on assets. This paper helped us think through some issues which recently have resurfaced with the work of Thomas Piketty. His earlier 1982 paper on speculation is also relevant to this topic. Most economists think of Tirole as game theory, finance, and industrial organization, but his contributions to finance are significant as well.

Just to show his breadth, here is his paper with Roland Benabou on incentives and when they undermine the intrinsic desire to do a good job. For instance if you pay kids to get good grades, will that backfire and kill off their own reasons for wanting to do well? Alex covers that paper in more detail. This other paper with Benabou, “Self-Confidence and Personal Motivation,” is a great deal of fun. It analyzes the benefits of overconfidence, namely greater motivation, and shows how to weigh those benefits against the possible costs, namely making more mistakes. It shows Tirole dipping a foot into the waters of behavioral economics and again reflects his versatility in terms of fields. I like this sentence from the abstract: “On the supply side, we develop a model of self-deception through endogenous memory that reconciles the motivated and rational features of human cognition.” Again with Benabou, here is his paper on willpower and personal rules, very much in the vein of Thomas Schelling.

Here is Tirole on intellectual property and health in developing countries, with plenty on policy.

It’s an excellent and well-deserved pick. One point is that some other economists, such as Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmstrom, may be disappointed they were not joint picks, this would have been the time to give them the prize too, so it seems their chances have gone down.

Overall I think of Tirole as in the tradition of French theorists starting with Cournot in 1838 (!) and Jules Dupuit in the 1840s, economics coming from a perspective with lots of math and maybe even some engineering. I don’t know anything specific about his politics, but to my eye he reads very much like a French technocrat in terms of approach and orientation.

Jean Tirole is renowned as an excellent teacher and a very nice person.

From the comments, on Bob Shiller and CAPE

For context, CAPE is the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio. On that topic, 3rdMoment writes:

While I have great respect for Shiller, I don’t understand his confidence that the CAPE is likely to return to it’s historical average of around 16. There are several reasons why we might expect the average CAPE going forward to be higher than in the past:

1. The average levels of CAPE in most of the last century appear, with hindsight, to have been puzzlingly low. This is the well-known “equity premium puzzle.”

2. There has been a large shift in corporate payout mix, from virtually all dividends in the past, to a roughly equal mix of dividends and share repurchases today. This by itself will add a couple of points to CAPE even if nothing else changes, (as shown in this post by the anonymous blogger who tweets as “Jesse Livermore”): http://www.philosophicaleconomics.com/2013/12/Shiller/

3. Some other accounting changes to the definition of profits might raise the CAPE as well, again see the linked blog post above.

4. Lower information and transaction costs and the rise of index investing have dramatically lowered the cost of maintaining a globally diversified portfolio. This decreases the raw rate of return for any given required rate of realized returns. For example if the costs of investing in equities fall by just 50 basis points, this would allow the required raw earnings yield to fall from 5% to 4.5%, corresponding to a rise in CAPE from 20 to 22, without changing realized returns for investors.

5. The real “risk free” return on treasuries seems to be very low by historic standards. Real returns on other forms of debt also appear low. This lowers the return stocks need to be attractive by comparison.

6. Large corporate cash balances, a “global savings glut,” lower rates of real economic growth, possible “secular stagnation,” all seem to point to the idea that real returns are somewhat harder to get than the past.

Some of these reasons are more certain than others, but taken together they seem to show that we have good reason to expect CAPE levels significantly above the historical average going forward.

Are there any countervailing reasons offsetting the list above, factors that would tend to make CAPE lower than in the past? I can’t really think of any. And I haven’t seen anybody else offering any.

Are real rates of return negative? Is the “natural” real rate of return negative?

Here is a long and very interesting post by Paul Krugman, also referencing a recent talk by Larry Summers. There is also this older Krugman post, and here is Gavyn Davies, and also Ryan Avent. And Scott Sumner. Do read and listen to these, there is much in there to ponder. I do very much agree with the claim that lower rates of return make recovery more difficult and for the longer haul as well. And I am happy to welcome these thinkers, or in the case of Krugman re-welcome, to stagnationist ideas.

I cannot, however, agree with the central arguments about negative real interest rates, and the necessity for negative natural rates of interest (there are a variety of interlocking claims here, so do read them for yourself. I am not sure any brief summary can quite reproduce the arguments, which are also not fully clear).

As I frame the data, we have had negative real rates on government securities, but positive rates on many other investments in the U.S. The difference reflects a very high real risk premium, which of course we would like to lower, and the differences also reflect some degree of investment segmentation. The positive rates on these other investments are evidenced by recent broad stock market gains, observed rates of productivity growth (low but clearly positive), high internal corporate hurdle rates, and so on. The “average vs. marginal” distinction is an important one, but still I don’t see how it can be used to push us away from seeing relevant real rates of return as positive. Nor do I think monopoly is widespread enough for that assumption to be a game-changer. Even Apple competes with Samsung and others in its major product lines.

Given the multiplicity of real rates in the American economy, I get nervous when I read about the real rate or the natural rate. (Don’t forget Sraffa [1932] and also Arnold Kling discusses the different issue of varying rates across people. Interfluidity questions whether the idea of a natural rate makes sense at all.) I also get nervous when I do not see serious talk about the embedded risk premium in the observed structure of market rates. I grow more nervous yet when the average vs. marginal question is not spelled out more explicitly.

In my view very negative real rates of return would not be a “natural rate” giving rise to full employment through a better equilibration of planned savings and investment. Given a pretty flat employment to population ratio, very negative real rates of return across the economy as a whole would have to mean negative economic growth and other attendant difficulties.

And no, I don’t think that output shrinkage associated with the persistently negative real interest rate would be expansionary through liquidity trap mechanisms; for one thing the negative wealth effect and the higher risk premium likely would offset the positive velocity effect on currency balances. The velocity effect on currency balances, from inflation, just isn’t that strong. At persistent negative rates of return we are much more likely to see an interdependence of AS and AD and some kind of cascading collapse of both. Or maybe it is simply better to say the framework has broken down than to try to squeeze one’s own predictions out of that set up.

Furthermore if you think destruction will help you ought then think that capital obsolescence will pull us out of Hansen’s long-term stagnation within five to ten years. On top of all that, I worry about the apparent “out of equilibrium” assumptions embedded in a model that has both a) negative real rates of return on investment and b) those investments being made in the first place, given that storage costs don’t seem to be enormously high.

I don’t mean this in a rude or polemic way, but the arguments we have been reading do not yet make sense.

Here is a claim I do find possible, although it is not one I am pushing. That would be a neo-Wicksellian argument that rates of return on capital are positive but low, and investors need low and indeed very negative borrowing rates to reflate the economy, given how high the risk premium is. I don’t read Krugman as promoting that view (note his citation of Samuelson’s OLG model for instance), although I think that is what the argument will have to boil down to. Otherwise it ends up being a call for output destruction, which, while I do understand how in some models at some margins that can help, I don’t think at current margins is going to be anything other than an unmitigated disaster. Literally.

I see it this way. If you are postulating a stagnation across the longer run, ultimately it will have to boil down to supply side deficiencies. The simple way to explain the mediocre recovery is to tack on slow growth assumptions to the underlying demand deficiencies. But that would constitute a big concession to real business cycle theory and it would put Thiel-Mandel-Gordon-Cowen stagnationist views in the driver’s seat, all the more so over time. The look back to Alvin Hansen is an effort to work in some (very much needed) stagnationist ideas, while at the same time doubling down on a demand-side perspective.

That just isn’t going to work.