Facts about Starbucks against free bathrooms charge them all

In May 2018, in response to protests, Starbucks changed its policies nationwide to allow anybody to sit in their stores and use the bathroom without making a purchase. Using a large panel of anonymized cellphone location data, we estimate that the policy led to a 7.3% decline in store attendance at Starbucks locations relative to other nearby coffee shops and restaurants. This decline cannot be calculated from Starbucks’ public disclosures, which lack the comparison group of other coffee shops. The decline in visits is around 84% larger for stores located near homeless shelters. The policy also affected the intensive margin of demand: remaining customers spent 4.1% less time in Starbucks relative to nearby coffee shops after the policy enactment. Wealthier customers reduced their visits more, but black and white customers were equally deterred. The policy led to fewer citations for public urination near Starbucks locations, but had no effect on other similar public order crimes. These results show the difficulties of companies attempting to provide public goods, as potential customers are crowded out by non-paying members of the public.

That is from a new paper by Umit Gurun, Jordan Nickerson, and David H. Solomon. Can there be any doubt about the excellence of Kevin Lewis?

Tim Ferriss did a podcast with me

Mostly he interviews me, the final segment is me interviewing him, the best part in my view. And they sent me this:

Thank you so much for being on the podcast! It was such a great interview. I just released it.Please see links below:Show notes on Tim’s blog: https://tim.blog/2020/03/05/tyler-cowen/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/p/B9XzpOTHSmX/

*The Origins of You: How Childhood Shapes Later Life*

That is the new forthcoming book by Jay Belsky, Avshalom Caspi, Terrie E. Moffitt, and Richie Poulton, which will prove one of the best and most important works of the last few years. Imagine following one thousand or so Dunedin New Zealanders for decades of their lives, up through age 38, and recording extensive data, and then doing the same for one thousand or so British twins through age 20, and 1500 American children, in fifteen different locales, up through age 15. Just imagine what you would learn!

You merely have to buy this book. In the meantime, let me give you just a few of the results.

The traits of being “undercontrolled” or “inhibited,” as a toddler are the traits most likely to persist up through age eighteen. The undercontrolled tend to end up as danger-seeking or impulsive. Those same individuals were most likely to have gambling disorders at age 32. Girls with an undercontrolled temperament, however, ran into much less later danger than did the boys, including for gambling.

“Social and economic wealth accumulated by the fourth decade of life also proved to be related to childhood self-control.” And yes that is with controls, including for childhood social class.

Being formally diagnosed with ADHD in childhood was statistically unrelated to being so diagnosed later in adult life. It did, however, predict elevated levels of “hyperactivity, inattentiveness, and impulsivity” later in adulthoood. I suspect that all reflects more poorly on the diagnoses than on the concept. By the way, decades later three-quarters of parents did not even remember their children receiving ADHD diagnoses, or exhibiting symptoms of ADHD (!).

Parenting styles are intergenerationally transmitted for mothers but not for fathers.

For one case the authors were able to measure for DNA and still they found that parenting styles affected the development of the children (p.104).

As for the effects of day care, it seems what matters for the mother-child relationship is the quantity of time spent by the mother taking care of the child, not the quality (p.166). For the intellectual development of the child, however, quality time matters not the quantity. By age four and a half, however, the children who spent more time in day care were more disobedient and aggressive. At least on average, those problems persist through the teen years. The good news is that quality of family environment growing up still matters more than day care.

But yet there is so much more! I have only scratched the surface of this fascinating book. I will not here betray the results on the effects of neighborhoods on children, for instance, among numerous other topics and questions. Or how about bullying? Early and persistent marijuana use? (Uh-oh) And what do we know about polygenic scores and career success? What can we learn about epigenetics by considering differential victimization of twins? What in youth predicts later telomere erosion?

I would describe the writing style as “clear and factual, but not entertaining.”

You can pre-order it here, one of the books of the year and maybe more, recommended of course.

Revisiting Latino economic assimilation

Here is a new paper by Giovanni Peri and Zachariah Rutledge

Using data from the United States spanning the period between 1970 and 2017, we analyze the economic assimilation of subsequent arrival cohorts of Mexican and Central American immigrants, the more economically disadvantaged group of immigrants. We compare their wage and employment probability to that of similarly aged and educated natives across various cohorts of entry. We find that all cohorts started with a disadvantage of 40-45 percent relative to the average US native, and eliminated about half of it in the 20 years after entry. They also started with no employment probability disadvantage at arrival and they overtook natives in employment rates so that they were 5-10 percent more likely to be employed 20 years after arrival. We also find that recent cohorts, arriving after 1995, did better than earlier cohorts both in initial gap and convergence. We show that Mexicans and Central Americans working in the construction sector and in urban areas did better in terms of gap and convergence than others. Finally, also for other immigrant groups, such as Chinese and Indians, recent cohorts did better than previous ones.

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Friday assorted links

1. Who are the Masters of Their Domains?

2. Austan Goolsbee on the vulnerability of the U.S. economy to coronavirus: so many face-to-face services (NYT).

4. More on the effective Taiwanese response to the coronavirus. And on the South Korean testing response.

Women in Economics: Janet Yellen

Here’s a great new video on Janet Yellen from our team at MRU. In addition to Yellen, the video features Ben Bernanke and Christina Romer, who is tremendous. Other videos in the series are on Anna Schwartz and Elinor Ostrom with more on the way. The video is excellent but my favorite MRU video with Yellen has her in superhero mode.

Instructors, feel free to use these videos in any of your classes. Of course, you can also find these videos integrated with our textbook.

By the way, here is Adams and Yellen’s classic paper on bundling (ungated) and you can find an introduction to bundling in this video.

Transcript of my Stanford talk on *Stubborn Attachments*

You will find it here, along with the video link, previously covered on MR without the transcript. Recommended, this was an almost entirely fresh talk. Here is my beginning paragraph:

I’d like to do something a little different in this talk from what is usually done. Typically, someone comes and they present their book. My book here, Stubborn Attachments. But rather than present it or argue for it, I’d like to try to give you all of the arguments against my thesis. I want to invite you into my internal monologue of how I think about what are the problems. It’s an unusual talk. I mean, I think talks are quite inefficient. Most of them I go to, I’m bored. Why are you all here? I wonder. I feel we should experiment more with how talks are presented, and this is one of my attempts to do that.

In the Q&A I also discuss how to eat well in the Bay Area.

Further results on social security wealth and inequality

From a recent paper by John Sabelhaus and Alice Henriques Volz:

…the present value of Social Security benefits for everyone who has paid anything into the system was $73.3 trillion in 2019. Thus, the present value of Social Security benefits is estimated to be roughly double all other household-sector pension and retirement account assets combined, and approximately three-fourths the size of all conventionally measured household net worth. Social Security is also an important retirement wealth equalizer, as employer-sponsored pension and retirement accounts accrue disproportionately to high wealth families.

…the bottom 50 percent of persons aged 35 to 44 in 2016 had average Bulletin net worth of only $13,500. However, the same group had average expected SSW of nearly $40,000, the difference between a PDV of benefits around $125,000 and a PDV of taxes around $85,000. Again, this is unsurprising given that low wealth individuals have much lower lifetime incomes, and the Social Security tax and benefit formulas are inherently progressive, even though differential mortality offsets some of that redistribution….although incorporating SSW into household wealth has a substantial impact on wealth inequality levels, it does not change overall trends in top wealth shares. While the top ten percent share of SCF Bulletin wealth (within age-sorted and person-weighted) increased from 58 percent to 66 percent between 1995 and 2016, the expanded wealth share that includes both DB wealth and SSW increased from 40 percent to 47 percent.

That is via the excellent David Splinter, one of the most important economists working today, and here is his new paper Presence and Persistence of Poverty in U.S. Tax Data. And here is the previous MR post on wealth inequality and social security.

From a scientist, coronavirus pictures to ponder

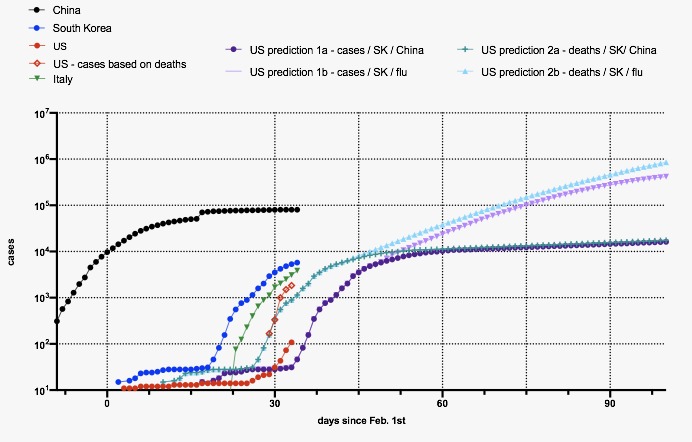

Figure legend

– Plotted in log scale!

– US cases based on deaths: estimated number of real cases using SK‘s current death rate of 0.6%

– US prediction 1a: predicted lower lower bound trajectory based on SK and China (assumes containment and large amount of testing )

– US 2a: upper bound, same assumptions as 1a

– US prediction 1b: no serious containment, trajectory similar to flu, lower bound

– 2b: Higher bound for flu-like trajectory

As I read this picture, it seems to suggest that the returns to properly done containment can be high. What do you all think?

Thursday assorted links

1. “The NWMC nongovernmental organization provides soft propaganda while they operate alongside the Russian military and imbed military tactics into foreign Russian populations through their corporate entity Wolf Holding of Security Structures.” (Huh?)

2. The heroism of Chinese doctors in Wuhan (WSJ, though I believe the paywall is off on this one). Recommended.

3. MIE: “A Coronavirus Pop-Up Shop Has Opened on Florida Avenue.”

5. Dan Klein on Smith, Hume, and Burke. And here.

6. Michael Strain on what to do (Bloomberg).

Our new world of classical music concerts

The line in the men’s room was to wash hands, not to use the other facilities. During the concert, there was remarkably little coughing compared to usual times. Is this because?:

1. The coughers were self-quarantining at home (there were more empty seats than usual).

2. Potential coughers didn’t want their seat neighbors to think of them as infecting pariahs.

3. Potential coughers abstained for fear of having to think, if they are coughing, that they might have coronavirus.

In any case, the elasticity of coughing with respect to self-reputation is higher than I had thought.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8-nWq6pqag

Yana and I were pleased to have watched from a private box (to be clear, we had a private box because the other people did not show up).

The Consequences of Treating Electricity as a Right

In poor countries the price of electricity is low, so low that “utilities lose money on every unit of electricity that they sell.” As a result, rationing and shortages are common. Writing in the JEP, Burgess, Greenstone, Ryan and Sudarshan argue that “these shortfalls arise as a consequence of treating electricity as a right, rather than as a private good.”

In poor countries the price of electricity is low, so low that “utilities lose money on every unit of electricity that they sell.” As a result, rationing and shortages are common. Writing in the JEP, Burgess, Greenstone, Ryan and Sudarshan argue that “these shortfalls arise as a consequence of treating electricity as a right, rather than as a private good.”

How can treating electricity as a right undermine the aim of universal access to reliable electricity? We argue that there are four steps. In step 1, because electricity is seen as a right, subsidies, theft, and nonpayment are widely tolerated. Bills that do not cover costs, unpaid bills, and illegal grid connections become an accepted part of the system. In step 2, electricity utilities—also known as distribution companies—lose money with each unit of electricity sold and in total lose large sums of money. Though governments provide support, at some point, budget constraints start to bind. In step 3, distribution companies have no option but to ration supply by limiting access and restricting hours of supply. In effect, distribution companies try to sell less of their product. In step 4, power supply is no longer governed by market forces. The link between payment and supply has been severed: those evading payment receive the same quality of supply as those who pay in full. The delinking of payment and supply reinforces the view described in step 1 that electricity is a right [and leads to] a low-quality, low-payment equilibrium.

The Burgess et al. analysis coheres with my observations in India where “wire anarchy” is common (see picture). It’s obvious that electricity is being stolen but no one does anything about it because it’s considered a right and a government that did do something about it would be voted out of power.

The stolen electricity means that the utility can’t cover its costs. Government subsidies are rarely enough to satisfy the demand at a zero or low price and so the utility rations.

The consequences for electricity consumers, both rich and poor, are severe. There is only one electricity grid, and it becomes impossible to offer a higher quantity or quality of supply to those consumers who are willing and sometimes even desperate to pay for it.

Moreover,the issue is not poverty per se.

…the vast majority of customers in Bihar expect no penalty from paying a bill late, illegally hooking into the grid, wiring around a meter, or even bribing electricity officials to avoid payment. These attitudes are in stark contrast to how the same consumers view payment for private goods like cellphones. It is debatable whether cellphones are more important than electricity, but in Bihar we find that the poor spend three times more on cellphones than they do on elec-tricity (1.7 versus 0.6 percent of total expenditure).

Burgess et al. frame the issue as “treating electricity as right,” but one can can also understand this equilibrium as arising from low state capacity and corruption, in particular corruption with theft. In corruption with theft the buyer pays say a meter reader to look the other way as they tap into the line and they get a lower price for electricity net of the bribe. Corruption with theft is a strong equilibrium because buyers who do not steal have higher costs and thus are driven out of the market. In addition, corruption with theft unites the buyer and the corrupt meter reader in secrecy, since both are gaining from the transaction. As Shleifer and Vishny note:

This result suggests that the first step to reduce corruption should be to create an accounting system that prevents theft from the government.

Burgess et al. agree noting, “reforms might seek to reduce theft of electricity and nonpayment of bills” and they point to programs in India and Pakistan that allow utilities to cut off entire neighborhoods when bills aren’t paid. Needless to say, such hardball tactics require some level of trust that when the bills are paid the electricity will be provided and at higher levels of quality–this may be easier to do when there are other sources of authority such as trusted religious leaders.

In essence the problem is that the government is too beholden to electricity consumers. If the government could commit to a regime of no or few subsidies, firms would supply electricity and prices would be low and quality high. But if firms do invest in the necessary electricity infrastructure the government will break its promise and exploit the firms for temporary electoral advantage. As a result, the consumers don’t get much electricity. The government faces a time consistency problem. Independent courts would help to bind the government but those often aren’t available in developing countries. Another possibility is a conservative electricity czar who, like a conservativer central banker, doesn’t share the preferences of the government or the voters. Again that requires some independence.

In short, to ensure that everyone has access to high quality electricity the government must credibly commit that electricity is not a right.

*Very Important People*

The author is Ashley Mears and the subtitle is Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit. I loved this book, my favorite of the year so far.

Haven’t you ever wondered why more books shouldn’t just take social phenomena and explain them, rather than preening their academic feathers with a lot of non-committal dense information? Well, this book tries to explain the Miami club where renting an ordinary table for the night costs 2k, with some spending up to 250k, along with the underlying sociological, economic, and anthropological mechanisms behind these arrangements. Here is just a start on the matter:

Any club, whether in a New York City basement or on a Saint-Tropez beach, is always shaped by a clear hierarchy. Fashion models signal the “A-list,” but girls are only half of the business model. There are a few different categories of men that every club owner wants inside, and there is a much larger category of men they aim to keep out.

Or this:

Bridge and tunnel, goons, and ghetto. These are men whose money can’t compensate for their perceived status inadequacies. The marks of their marginal class positions are written on their bodies, flagging an automatic reject at the door.

A clever man can try to use models as leverage to gain entry and discounts at clubs. A man surrounded by models will not have to spend as much on bottles. I interviewed clients who talked explicitly about girls as bargaining chips they could use at the door.

The older, uglier men may have to pay 2k to rent a table for the evening, whereas “decent-looking guys with three or four models” will be let in for free with no required minimum. And:

Men familiar with the scene make these calculations even if they have money to spend: How many beautiful girls can I get to offset how I look? How many beautiful girls will it take to offset the men with me? How much money am I willing to spend for the night in the absence of quality girls?

How is this for a brutal sentence?:

Girls determine hierarchies of clubs, the quality of people inside, and how much money is spent.

Here is another ouch moment:

…I revisit a second critical insight of Veblen’s on the role of women in communicating men’s status. In this world, girls function as a form of capital. Their beauty generates enormous symbolic and economic resources for the men in their presence, but that capital is worth far more to men than to the girls who embody it.

if you ever needed to be convinced not to eat out at places with beautiful women, this book will do the trick. Solve for the equilibrium, people…

You can pre-order here. (By the way, I’ve been thinking of writing more about “lookism,” and why opponents of various other bad “isms” have such a hard time extending the campaign to that front.)

Wednesday assorted links

1. Productivity claims made by Daniel Gross, channeled by Erik Torenberg.

2. L. Summers on the appropriate response to the coronavirus.

3. Gender and the consulting academic economist.

4. New Steve Davis and Kevin Murphy economics podcast.

5. New Zealand birds are capable of statistical inference.

Donald Trump tweets my column

But they really knew who was going to win! https://t.co/WZnOx6ZHmW

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 4, 2020

Please don’t even try reading the comments on this post.