What can we learn from the history of The Machinery Question?

Recently I read was Peter Gaskell’s Artisans and Machinery, from 1836 (later reprinted).

So much of his discussion of handloom weavers could come out of an Atlantic Monthly article from 2015, albeit with different historical references. However today’s stories typically claim that automation favors tech skills, whereas Gaskell argues power weaving put the skilled workers out of jobs and empowered the less skilled machine supervisors.

Just as Bill Gates called for the taxing of robots, back in the early 19th century many people called for the taxing of machinery. Gaskell believes this would help labor in the short run but in the longer run actually stimulate more innovation — to avoid some of the tax by lowering capital costs — eventually making labor’s lot all the worse.

Gaskell dives into sociology and suggests that the earlier, less technology-intensive workers were more religious, more devout, and less likely to make political trouble. Distinctions of rank were in fuller force, and children were less likely to be pressured to work outside the home. Insofar as the man worked inside the cottage as a sole proprietor, this encouraged an ethic of individual responsibility. Society was truly decentralized, and those were “the golden times” of manufactures. The downside is that such individuals were less likely to be literate, and of course output was lower, including food output, and prices were higher.

Since women and children also could work the new power looms, that increased the supply of labor and put downward pressure on wages and on male wages in particular. Collectively speaking, it would have been better to preserve division of labor within the household, and keep male wages relatively high, and female household production relatively high.

One of the more charming sections of this book was the chapter on how factories spur too much of the animal passions, as men and women are working together long hours and will eventually…dine with Mike Pence. Furthermore, factory work leads to new norms where women can have premarital sex and still expect to marry someone else later on, without much fear of a reputational penalty. Premarital sex then rises all the more, and then the looser norms are passed down to the children, worsening the problem all the more. Eventually England will end up with the sexual norms found in the “warmer climates.”

Overall, Gaskell paints a picture of a world where there are positive social externalities from having individual males tied to pieces of land. Along those lines, he offers a kind of Georgist critique of the countryside, where too much land has been tied up in speculative enclosures.

Given ongoing mechanization, only in the long run can a society find a “healthy and permanent tone” once again. He is optimistic about the long run, but not about the transition.

I don’t exactly agree with all of these perspectives, but I was impressed by the intricacy and also clarity of the analysis in this book, which usually does not receive significant mention in the history of economic thought.

Here are various copies of the book. Even Maxine Berg doesn’t cover Gaskell much.

Voluntary dining in hospitals

Label this not The Department of Why Not but rather The Department of Why?

The Howsers are far from the only regulars at the Castle Creek Cafe, located inside Aspen Valley Hospital. It’s a popular breakfast spot for city workers. It also feeds people on both sides of the law; police officers visit daily, and the cafe delivers to inmates at the local jail 7 days a week. The cafe makes a point of welcoming community members with no hospital affiliation. And its menus, made available to view a month at a time, include items like herbed farro pilaf, corn soufflé, and panko crusted cod. We’re a long way away from institutional slop. [TC: speak for yourself, buster!]

The Howsers discovered the cafe, which Mary calls “the best kept secret in Aspen,” after having some tests done in the hospital. She says, “Never in my wildest dreams did I think hospital food could be tasty!” The experience has even inspired them to check out restaurants at other hospitals.

One Colorado hospital restaurant that should be next on their list is Manna, within Castle Rock Adventist Hospital.

I am sorry people, but I am going to stick with theory on this one. No data will be sampled, unless you count this enthusiastic description from Tim Davis as evidence of sorts:

“Their menu has real gourmet style food you would expect from a high priced restaurant, but sold to you at a much more affordable price,” he says. One dish is maple glazed duck confit, consisting of a maple glazed duck leg served with swiss chard and spätzle, for $9. The grilled Thai cabbage steak, with marinated cabbage, spicy lime dressing, and shishito pepper, is even cheaper. Their burger buns even come adorned with a monogrammed M.

A further advantage is that the staff don’t push you out the door to leave, in addition the dining rooms are spacious and somber.

Mises was right about the a priori!

Here is the article, with further testimonials, and for the hat tip I thank Steve Rossi.

Thursday assorted links

1. The rising popularity of Indian food in Britain, circa 1957.

2. How do you eat your chocolate bunny? (Cowen’s Second Law) “Vast majority prefer to start with the ears.” Here is the original research.

3. I have seen the homeless in San Francisco do far worse than this. And bring back the granny flat.

Alcohol Bans in India and the United States

The Indian Supreme Court has just banned sales of alcohol within 500 meters of a national highway. The ban affects not just liquor stores but tens of thousands of restaurants and hotels. In response, the Rajasthan Public Works Department announced that they would now recategorize highways in urban areas as roads! Other states may follow suit. (David Keohane at the FT has further background on the India ban.)

Lost in the shenanigans is that even if the ban were implemented perfectly it’s not at all obvious that it would reduce traffic accidents. Alcohol can be easily stored and if you are thirsty driving 500 meters doesn’t seem like very far to go to buy alcohol.

Entire counties in the United States have banned alcohol but that doesn’t seem to have reduced traffic fatalities. It may even have increased fatalities because residents of dry counties drive to a wet county to find a bar and then they drive drunk for longer distances as they head home.

The surveillance culture that is Sweden

The syringe slides in between the thumb and index finger. Then, with a click, a microchip is injected in the employee’s hand. Another “cyborg” is created.

What could pass for a dystopian vision of the workplace is almost routine at the Swedish startup hub Epicenter. The company offers to implant its workers and startup members with microchips the size of grains of rice that function as swipe cards: to open doors, operate printers, or buy smoothies with a wave of the hand.

The injections have become so popular that workers at Epicenter hold parties for those willing to get implanted.

“The biggest benefit I think is convenience,” said Patrick Mesterton, co-founder and CEO of Epicenter. As a demonstration, he unlocks a door by merely waving near it. “It basically replaces a lot of things you have, other communication devices, whether it be credit cards or keys.”

Here is more, via Samir Varma. Personally, I would rather sponsor a few seats at that crucifixion in Manchester…or better yet sit next to the bishop.

Thwarted Manchestertum markets in everything

A fundraising plan to hold a mock crucifixion of members of the public in Manchester city centre has been cancelled after Church of England clergy raised concerns it was blasphemous and unsafe.

Organisers of the Manchester Passion Play, which will tell the story of Christ’s crucifixion in the city’s Cathedral Gardens on Saturday, offered “the full crucifixion experience” for £750.

The offer, posted on the Manchester Passion 2017 Crowdfunder site, was removed after members of the play’s organising committee, which includes C of E clergy, expressed concerns it was potentially dangerous and blasphemous.

Reverend Falak Sher, a canon at Manchester Cathedral and chairman of the organising committee, said he vetoed the idea when it came to light.

He said: “When I saw it I did not like it, I thought it was disgraceful. The whole message of the cross is hope and love. When I saw this I was not very happy and asked the committee to take this one down.

“We didn’t like promoting the event in this way for £750. I thought it was not a very positive message when dealing with a message of love and hope.”

And yet the article gets better, and indeed draws upon economic analysis:

Stewart-Clark, who runs a business importing timber, said that the event had grown since it was first conceived to include a cast of 120, and 80 stewards. “The whole thing just got bigger and bigger and, of course, with that comes the infrastructure cost,” he said.

“Instead of being a £20,000 play it became a £55,000 play and the burden on raising money then falls on us. We were trying to think up some ideas, just bouncing around what would be good, and someone came up with the idea of letting people be crucified for £750.”

Stewart-Clark said that he did not think the idea was blasphemous, but that it was on “the grey line” and tasteless. “You have clergy wanting to play it safe and businessmen like me trying to raise the funding,” said Stewart-Clark. “There was a difference of opinion and what was a small disagreement has got out of all proportion.”

I enjoyed this sentence:

He said that he had never known anyone to fall off such a cross.

And this one:

Stewart-Clark said there were plenty of other bad fundraising ideas that were scrapped, including charging people a fee to sit next to the bishop to watch the play.

Here is the full article, interesting throughout, and with a photo of the initial fundraising ad. For the pointer I thank John B.

*Corruption: What Everyone Needs to Know*

That is by Ray Fisman and Miriam A. Golden, an excellent book, the subtitle says it all. And yes it does also cover how to stop or at least limit corruption.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Are rents in high-productivity cities actually starting to fall? And the dark side of cities? (speculative)

2. One way, using book recommendations, to understand who is on Quora.

3. In which regions are Americans most likely to wear seat belts? And does the Alt Right love single payer health care?

4. Bryan Caplan on the rationality community. I don’t think he agrees with this framing, but I read him as more critical of their rationality than I am.

5. Why new foods taste better when you’re on vacation. And sex differences in the human brain.

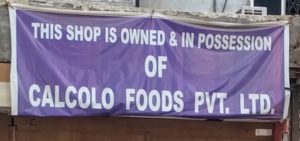

In India Possession is Maybe 6/10th of the Law

In India you will often see signs asserting Ownership and Possession on buildings and lots that are  unoccupied or under construction. The reason is not to stop squatters but rather to avoid the double selling problem. In the United States, it’s fairly easy to find out who owns a piece of land or even an expensive asset like a car. The land registry and titling system in India, however, is expensive and not always easy to check. As Gulzar Natarajan writes:

unoccupied or under construction. The reason is not to stop squatters but rather to avoid the double selling problem. In the United States, it’s fairly easy to find out who owns a piece of land or even an expensive asset like a car. The land registry and titling system in India, however, is expensive and not always easy to check. As Gulzar Natarajan writes:

For something so valuable, land records in most developing countries are archaic. No register, which reliably confirms title, exists anywhere in India. Small experiments in some states to build such register have not been successful. Existing registers suffer from problems arising from lack of updation, fragmentation of lands, informal family partitions, unregistered power of attorney transactions, and numerous boundary and ownership disputes. The magnitude of these problems gets amplified manifold in urban areas.

It’s possible, for example, for a family member to sell family land without anyone else knowing about it. In Muslim customary law, gifts made on the deathbed can override a will which (surprise!) tends to benefit late-stage caregivers. Verbal deals in general are not uncommon.

Indeed, without proper land registration it’s possible for an entirely unconnected person to sell land that he doesn’t own. Even if the real owners have some type of title, the ensuing court process between the real owners and those who thought or claimed they were the real owners will be time and wealth consuming. Forged documents are common. A large majority of all legal cases in India’s clogged court system are property disputes. The best thing is to occupy the land but if you can’t do that you want to signpost the land to make it as clear as possible who owns it so if someone is offered the land for sale they know who to call to verify.

Indeed, without proper land registration it’s possible for an entirely unconnected person to sell land that he doesn’t own. Even if the real owners have some type of title, the ensuing court process between the real owners and those who thought or claimed they were the real owners will be time and wealth consuming. Forged documents are common. A large majority of all legal cases in India’s clogged court system are property disputes. The best thing is to occupy the land but if you can’t do that you want to signpost the land to make it as clear as possible who owns it so if someone is offered the land for sale they know who to call to verify.

Signposting is an old device for avoiding the double spending/selling problem by making ownership claims public and verifiable. The blockchain ledger is a modern version. A land registry system on the blockchain could work and systems are being tested in Sweden, Georgia and Cook County. Implementing such systems, however, first requires that land be mapped and parceled–and in many states in India the last land surveys were done by the British before independence. Surveys are becoming easier with drones and automatic surveying but India’s land surveying, registering and titling system still has a long way to go.

Are weak ties less important for job-seeking?

…I argue that new technologies have changed the kinds of problems people face when searching for a job. The problem is no longer, as it was in the 1970s, discovering that the job opening exists in the first place. Instead, job seekers’ major problem is ensuring that someone notices their resume now that so many people are applying to every job opening. When you want your resume to be noticed, it turns out that workplace ties — people who can speak to what you are like as a worker — help white-collar job seekers much more than weak ties do (61 percent of my sample were helped by workplace ties, and 17 percent were helped by weak ties). This is not to say that Granovetter’s study is wrong, but rather that is is a grounded snapshot of a historical moment.

That is from the quite good and surprisingly substantive Down and Out in the New Economy: How People Find (or Don’t Find) Work Today, by Ilana Gershon.

Pay equality and treatment inequality within the corporation

One question is how much firms pay men and women, relative to their marginal products; here are some previous MR posts on that topic. A second question, neglected somewhat by economists (but not ignored more generally), is how men and women (and other genders) treat each other within the firm.

To go down this purely hypothetical path, let’s say a firm pays women their full and fair market value, but the firm is embedded in a city where men lord it over women, perhaps because of income inequality and unequal ratios in the dating market. Within that company, men may treat women in unfair ways. They may harass them, or simply listen to them less, or perhaps refuse to serve as mentors. The surrounding urban culture makes this a stable equilibrium, because the men in this company do not need the women so much for their preferred “total life portfolio” of gender relations. For purposes of contrast, if men need their particular workplace to date and marry suitable women, or even just have them as friends or mentors, those men will treat these women more courteously. (NB: is there an equilibrium where this attention leads to worse treatment? Maybe sometimes the women simply prefer to be ignored. I have heard that male tourists in Bangkok do not hit on the female tourists they meet there, for instance.)

The (fair) firm will fire egregious male offenders of the company’s norms, but some of these offenses are neither observable nor contractible. So imagine the firm setting the wage first, and then the men within that company claw back some of the employee surplus of the women by harassing those women.

The more fairly the company pays women, the more men within that company can harass the women, if only because the women are less likely to leave the company (the participation constraint).

So some of the benefit of paying women their fair share ends up distributed to those men, within the company, who wish to harass or otherwise mistreat those women. And of course the unfair treatment of women does not have to come from harassers, or even from men. It also could come from other women, or from relatively impersonal processes, such as inquiries and tribunals, which perhaps in some manner, possibly unintentionally, are less well geared to represents the interests of women. So you should interpret that word “harassment” in the broadest possible sense.

One prediction of this model is a good deal of harassment in sectors that have relatively strong pay equity norms. Furthermore, men bent on harassment or mistreatment of women may be among the biggest supporters of pay equity within their institutions.

The greater you think is the scope for potential male mistreatment of women, the weaker is the pecuniary case for pay equity norms, at least in a short-run, partial equilibrium setting (you might think in the longer run you can shift all the norms with tough, across-the-board enforcement).

Conversely, imagine you can shift the norms within a company so the male employees treat the female employees better. That weakens the pressures for the company to pay the women their full marginal products. Even a company bent on “being fair” may find it hard to spot the underpaid women, because they are not always leaving and revealing that better pay should be offered.

A broader point is that the ethos of a company can only deviate from the ethos of its geographic location by so much.

Of course that is all just in the model, the real world is quite different. In the real world, selection and clustering effects overwhelm the logic of compensating differentials, so there are good institutions and bad institutions. The good institutions pay the women what they deserve, and have stronger norms against harassment and bad treatment. All goes well there, and for that reason it is not hard to tell which are the good institutions and the bad institutions.

Do safe cars cost more to ensure?

New cars loaded with high-tech crash-prevention gear are having a perverse effect on car-insurance costs: They are soaring.

Safety features such as autonomous braking and systems to prevent drivers from drifting out of their lanes are increasingly available on vehicles rolling off assembly lines. Auto companies and third-party researchers say these features help prevent crashes and are building blocks to self-driving cars. But progress comes with a price.

Enabling the safety tech are cameras, sensors, microprocessors and other hardware whose repair costs can be more than five times that of conventional parts. And the equipment is often located in bumpers, fenders and external mirrors—the very spots that tend to get hit in a crash. Insurance companies, unwilling to shoulder all the pain, are passing some of the cost off to buyers.

Here is more from Christina Rogers and Leslie Scism at the WSJ.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Stripe is hiring an economist.

2. Might Seattle move away from NIMBY?

3. No strong evidence yet that smartphones are making us stupider.

4. Dolphin vs. octopus strategies.

5. Fatal injury aside, U.S. life expectancy is at the top.

6. Who is to blame for the judicial confirmation wars?

7. Tesla surpasses Ford in market value (NYT).

MRU video on The Great Reset

Why is authoritarianism on the rise?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit from it:

You can scold the sympathizers for their naivete or illiberal tendencies, but there is a deeper truth. Individuals have a mimetic desire to copy or praise or affiliate what is perceived as successful, and a lot of our metrics of success have to do with power rather than freedom or prosperity. So if there is a powerful system on the world stage, many of us will be drawn to it and seek to emulate it, without always being conscious of the reasons for those attractions.

This process is actually not so different from how neoliberalism attracted greater support during the 1990s, when it was perceived as the major victor on the world stage. We neoliberals liked to think that the rest of the world “finally saw the light,” but a more sober retrospective assessment is that much of the popularity boom of neoliberalism was temporary, to be wiped out by status-lowering developments, including the financial crisis and slower real wage growth.

These chains of ideological influence can be remarkably indirect. For instance, it is commonly believed that the collapse of Soviet communism led to a softening of positions within the Irish Republican Army. It’s not that anyone ever expected the Soviets to intervene in the Irish conflict, but rather a role model of resistance had been taken away, and this ultimately made the peace process easier.

There is much more at the link, none of it especially cheery. By the way, I hope you know better than to read the piece as recommending authoritarian economic policy — stay awake!