Tuesday assorted links

1. Writing an economics paper using LLMs entirely. Sort of.

2. The most beautiful words in the English language? The o3 list is better.

3. The macroeconomics of tariffs and retaliation. The real news here is the claim that, in the absence of foreign retaliation, the tariffs will make America better off. Typically I am skeptical of such conclusions, due to the importance of more dynamic factors, including those of public choice, but in any case I expect that finding will be underreported.

4. China’s One Child Policy lowered fertility more than we used to think.

5. Daniel Muñoz on Coleman Hughes and the norm of colorblindness. A very good piece.

Has Clothing Declined in Quality?

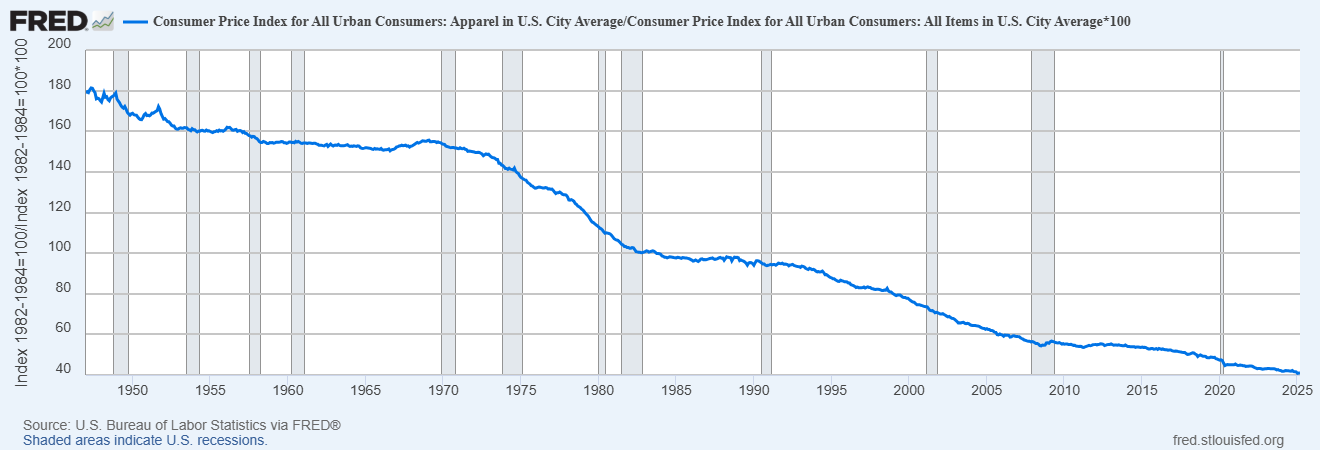

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) recently tweeted that they wanted to bring back apparel manufacturing to the United States. Why would anyone want more jobs with long hours and low pay, whether historically in the US or currently in places like Bangladesh? Thanks in part to international trade, the real price of clothing has fallen dramatically (see figure below). Clothing expenditure dropped from 9-10% of household budgets in the 1960s (down from 14% in 1900) to about 3% today.

Apparently, however, not everyone agrees. While some responses to my tweet revealed misunderstandings of basic economics, one interesting counter-claim emerged–the low price of imported clothing has been a false bargain, the argument goes, because the quality of clothing has fallen.

The idea that clothing has fallen in quality is very common (although it’s worth noting that this complaint was also made more than 50 years ago, suggesting a nostalgia bias, like the fact that the kids today are always going to hell). But are there reliable statistics documenting a decline in quality? In some cases, there are! For example, jeans from the 1960s-80s, for example, were often 13–16 oz denim, compared to 9–11 oz today. According to some sources, the average garment life is down modestly. The statistical evidence is not great but the anecdotes are widespread and I shall accept them. Most sources date the decline in quality to the fast fashion trend which took off in the 1990s and that provides a clue to what is really going on.

Fast fashion, led by firms like Zara, is a business model that focuses on rapidly transforming street style and runway trends into mass-produced, low-cost clothing—sometimes from runway to store within weeks. The model is not about timeless style but about synchronized consumption: aligning production with ephemeral cultural signals, i.e. to be fashionable, which is to say to be on trend, au-courant and of the moment.

It doesn’t make sense to criticize fast fashion for lacking durability—by design, it isn’t meant to last. Making it durable would actually be wasteful. The product isn’t just clothing; it’s fashionable clothing. And in that sense, quality has improved: fast fashion is better than ever at delivering what’s current. Critics who lament declining quality miss the point—it’s fun to buy new clothes and if consumers want to buy new clothes it doesn’t make sense to produce long lasting clothes. People do own many more pieces of clothing today than in the past but the flow is the fun.

So my argument is that the decline in “quality” clothing has little to do with the shift to importing but instead is consumer-driven and better understood as an increase in the quality of fashion. Testing my theory isn’t hard. Consider clothing where function, not just fashion, is paramount: performance sportswear and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

There has been a massive and obvious improvement in functional clothing. The latest GoreTex jackets, for example, are more than five times as water resistant (28 000 mm hydrostatic head) compared to the best waxed cotton technology of the past (~5 000 mm) and they are breathable (!) and lighter. Or consider PolarTec winter jackets, originally developed for the military these jackets have the incredible property of releasing heat when you are active but holding it in when you are inactive. (In the past, mountain climbers and workers in extreme environments had to strip on or off layers to prevent over-heating or freezing while exerting effort or resting.) Amazing new super shoes can actually help runners to run faster! Now that is high quality. Personal protective equipment has also increased in quality dramatically. Industrial workers and intense sports enthusiasts can now wear impact resistant gloves which use non-Newtonian polymers that stiffen on impact to reduce hand injuries.

Moreover, it’s not just functional clothing that has increased in quality. For those willing to look, there is in fact plenty of high-quality clothing readily available. From Iron Heart, for example, you can buy jeans made with 21oz selvedge indigo denim produced in Japan. Pair with a high-quality Ralph Lauren shirt, a Mackinaw Wool Cruiser Jacket and a nice pair of Alden boots. Experts like the excellent Derek Guy regularly highlight such high-quality options. Of course, when Derek Guy discusses clothes like this people complain about the price and accuse him of being an elitist snob. Sigh. Tradeoffs are everywhere.

Moreover, it’s not just functional clothing that has increased in quality. For those willing to look, there is in fact plenty of high-quality clothing readily available. From Iron Heart, for example, you can buy jeans made with 21oz selvedge indigo denim produced in Japan. Pair with a high-quality Ralph Lauren shirt, a Mackinaw Wool Cruiser Jacket and a nice pair of Alden boots. Experts like the excellent Derek Guy regularly highlight such high-quality options. Of course, when Derek Guy discusses clothes like this people complain about the price and accuse him of being an elitist snob. Sigh. Tradeoffs are everywhere.

Critics long for a past when goods were cheap, high quality, and Made in America—but that era never really existed. Clothing in the past was more expensive and often low quality. To the extent that some products in the past were of higher quality–heavier fabric jeans, for example–that was often because the producers of the time couldn’t produce it less expensively. Technology and trade have increased variety along many dimensions, including quality. As with fast fashion, lower quality on some dimensions can often produce a superior product. And, of course, it should be obvious but it needs saying: products made abroad can be just as good—or better—than those made domestically. Where something is made tells you little about how well it’s made.

The bottom line is that international trade has brought us more options and if today’s household were to redirect the historical 9 – 10 % share of income to clothing, it could absolutely buy garments that are heavier, better-constructed, and longer-lived than the typical mid-century mass-market clothing.

Tabarrok on the Movie Tariff

The Hollywood Reporter has a good piece on Trump’s proposed movie tariffs:

Even if such a tariff were legal — and there is some debate about whether Trump has the authority to impose such levies — industry experts are baffled as to how, in practice, a “movie tariff” would work.

“What exactly does he want to put a tariff on: A film’s production budget, the level of foreign tax incentive, its ticket receipts in the U.S.?” asks David Garrett of international film sales group Mister Smith Entertainment.

Details, as so often with Trump, are vague. What precisely constitutes a “foreign” production is unclear. Does a production need to be majority shot outside America — Warner Bros’ A Minecraft Movie, say, which filmed in New Zealand and Canada, or Paramount’s Gladiator II, shot in Morocco, Malta and the U.K. — to qualify as “foreign” under the tariffs, or is it enough to have some foreign locations? Marvel Studios’ Thunderbolts*, for example, had some location shooting in Malaysia but did the bulk of its production in the U.S, in Atlanta, New York and Utah.

…“The only certainty right now is uncertainty,” notes Martin Moszkowicz, a producer for German mini-major Constantin, whose credits including Monster Hunter and Resident Evil: The Final Chapter. “That’s not good for business.”

A movie producer is quoted on the bottom line:

“Consistent with everything Trump does and says, this is an erratic, ill conceived and poorly considered action,” says Nicholas Tabarrok of Darius Films, a production house with offices in Los Angeles and Toronto. “It will adversely affect everyone. U.S. studios, distributors, and filmmakers will suffer as much as international ones. Trump just doesn’t seem to understand that international trade is good for both parties and tariffs not only penalize international companies but also raise prices for U.S. based companies and consumers. This is an ‘everyone loses, no one gains’ policy.”

Guatemala vs. El Salvador

Guatemala has a slight edge on GNP per capita, according to World Bank sources $5762 vs. $5391, noting the gap has grown a bit since these 2023 measurements.

When I visited El Salvador, people spoke enviously of the economy of Guatemala. Over the last twenty-two years, the gdp growth rate in Guatemala has averaged 3.5%, and the country still is growing in that range. El Salvador recently was growing at 3.18%, but historically has had much lower growth rates.

Guatemala, with over eighteen million people, has greater scale. El Salvador has somewhat over six million people. Guatemala is above replacement rates with its TFR at 2.3, El Salvador is below replacement at 1.7. Both countries lose people to the United States.

By most measures, Guatemala has a better economy than El Salvador, albeit to a modest degree. You would put both countries at the same general level of economic development. Overall democracy is in better shape in Guatemala.

One hears much more about El Salvador these days, partly for “culture war” reasons. But putting aside Panama, it is Guatemala that has to count as the relative economic success story of Central America. There is room for plenty more progress, but this is by no means a hopeless situation.

Who’s next?

The United Arab Emirates will introduce artificial intelligence to the public school curriculum this year, as the Gulf country vies to become a regional powerhouse for AI development.

The subject will be rolled out in the 2025-2026 academic year for kindergarten pupils through to 12th grade, state-run news agency WAM reported on Sunday. The course includes ethical awareness as well as foundational concepts and real-world applications, it said.

The UAE joins a growing group of countries integrating AI into school education. Beijing announced a similar move to roll out AI courses to primary and secondary students in China last month.

The Gulf state has invested extensively in data centers used to train AI models and has set up an AI investment fund that people familiar with the project said could swell to more than $100 billion in a few years.

Here is more from Sara Gharaibeh at Bloomberg. Via Anecdotal.

Latin America is swinging to the traditional, non-Trumpian right

With the far right ascendant in much of the west, it is notable that Latin America is not turning the same way, to a Trumpian closed economy. It is favouring leaders with more traditional agendas, based on free markets and open economies. This increases the region’s chances of escaping its damaging growth slump and attracting capital in this post-American exceptionalism world.

Lady Liberty of the Pacific

Instead of re-opening Alcatraz as super-max prison we should build a statue to America. I suggest “Lady Liberty of the Pacific”. The spirit of Columbia ala John Gast’s American Progress carrying a welcoming beacon-lamp in her raised right hand and a coiled fibre-optic cable in her left representing Bay Area technology.

Monday assorted links

How are economics publications changing?

This study examines publications in three leading general economics journals from the 1960s through the 2020s, considering levels and trends in the demographics of authors, methodologies of the studies, and patterns of co-authorship. The average age of authors has increased nearly steadily; there has been a sharp increase in the fraction of female authors; the number of authors per paper has risen steadily; and there has been a pronounced shift to articles using newly generated data. All but the first of these trends have been most pronounced in the most recent decade. The study also examines the relationships among these trends.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Daniel Hamermesh.

AI-assisted time saved at work so far

Between 1 and 5% of all work hours are currently assisted by generative AI, and respondents report time savings equivalent to 1.4% of total work hours.

That is from a 2025 paper by Alexander Bick, Adam Blandin, and David J. Deming.

Emergent Ventures, 9th India cohort

Ari Dutilh is a 19-year-old entrepreneur, community builder, and photographer. This grant is to help continue our work on UltraRice, a project to solve malnutrition in India by using ultrasonic treatment to create cost-effective, nutrient-scalable rice.

Rukmini S is Founder and Director of Data For India. Rukmini is an award-winning data journalist and won her first EV prize for her pandemic podcast, ‘The Moving Curve’. Her first book, ‘Whole Numbers & Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About Modern India’ awon literary awards.

Sworna Jung Khadka is an ESG entrepreneur. Stalwart International Private Limited is an agro startup funded by Emergent Ventures which leases unused government owned lands and non-agricultural but arable lands for the production of Cassava, drought resistant crops.

Suryesh Kumar Namdeo is a Senior Research Analyst at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, working on biosecurity policy and science diplomacy projects. He has received his EV grant to support his research and conference travels in biosecurity policy in India.

Susan Thomas – XKDR Forum aims to help litigants in India get more predictability about how their legal cases will progress in Indian courts. They propose to publish specific metrics of case progression, at a quarterly frequency, by developing a database of commercial cases from multiple courts in India. You can read more about XKDR Forum’s work in this field here.

Jayesh Rohatgi is an entrepreneur and law student at LSE, with an educational startup, Dialogue Dynamics. Targeting top independent schools globally, Dialogue Dynamics focuses on the four most critical sub-skills of communication: presenting viewpoints, strategic questioning, identifying misinformation, and mastering persuasion.

Aakash Agrawal is a neuroscience and AI researcher who investigates the neural mechanisms that enable fluent reading. He aims to leverage his research and develop gamified cognitive tasks to help children improve their reading skills without adult supervision.

Ada Choudhry is an 18-year-old student from Bareilly, India, who received an EV grant to build AI supply chain platforms under the mentorship of Shell executives. The goal is to reduce supply chain risk and improve procurement data quality. She will be beginning her undergraduate studies at Minerva University in San Francisco, and you can look through her portfolio here!

Aditya Kedlaya is a hardware product designer and entrepreneur from Bangalore. He received his EV grant to develop prototypes of carbon capture modules through his startup. He founded Matterak Technologies to design, develop and deploy products related to decarbonization including carbon capture, infrastructure for carbon neutral fuels production and energy efficient hardware.

Adon Banker, is 16 years old and currently enrolled in the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program at Chatrabhuj Narsee School, Mumbai, with a major in Computer Science. His project, the Jewish Virtual Museum, aims to create a lasting legacy for the Bene Israel community in the history of India. He also will develop an application that analyzes antisemitism globally in real-time using Twitter data.

Aishwarya Das, from Bangalore, is the co-founder of Dirac Labs, a spin-off from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His team is developing quantum magnetometers for GPS-free navigation.

Akash Kumar Seth, a software developer, is working on freeCodeProjects.org, which will help potential students become job-ready under the mentorship of experienced developers absolutely free.

Ayush Majumdar, 22, originally from Calcutta, is a writer and translator currently translating the works of Rabindranath Tagore.

Chetan Kandpal works in computer science, cognitive science, and now neuroscience, and his research delves into human social dynamics, particularly how information transmission and normative assumptions are influenced by the presence of agents in multi-agent environments. Chetan received the EV grant for the opportunity to present his work on social dynamics at MIT.

Balaji Bangolae Lakshmikanth, Dr. Lakshmi Santhanam, and Deepika Gopal are the founders of Renkube, a deep-tech solar startup to lower cost and increase safety. The EV grant will support their efforts in creating a Fire Prediction and Prevention solution for rooftop solar installations, aimed at preventing fire accidents and improving overall safety.

Digvijay Singh is building large scale diagnostics (LSDs) at Drizzle Health to eliminate epidemics by testing large volumes of food, water, and eventually air in real-time.

Druhin Lamba is a BS-MS student in Mathematics and Computing at IIT Roorkee. He received his EV grant for education and career development.

Khushi Mittal is a 20-year-old from Lucknow and is interested in propulsion systems. She received an EV grant to take a gap year from University of Alberta in Canada and move to Bangalore to work on her projects related to aerospace and build a hardware community with the Wayfarers group.

Manas Goyal, a 23-year-old Impact Finance entrepreneur, is the founder of All Asia NetBanking, a platform dedicated to providing accessible and seamless banking solutions. He received an EV grant to develop a new, innovative model that simplifies access to unified banking solutions. Currently based in the US at MIT, Manas is focused on making banking easier and more accessible for everyone.

I thank Shruti Rajagopalan for the information and selection. And here is Nabeel’s AI engine for other EV winners. Here are the other EV cohorts.

Trump proposes 100% tariff on movies shot outside the United States

Here is one link. Of course the proposal is not easy to understand. If it is a Jason Bourne movie, do they add up the number of scenes shot abroad and consider those as a percentage of the entire movie? Does one scene shot abroad invoke the entire tariff? o3 guesstimates that about half of major Hollywood releases are shot abroad to a significant degree, with many more having particular scenes shot abroad.

Imagine the new Amazon release: “James Bond in Seattle.” And it actually would be Seattle — do they have baccarat there?

Furthermore, virtually all foreign films are shot abroad rather than in the U.S. The incidence in this case is interesting. Assuming the movie would have been made anyway, most of the tax burden falls on the producer, not the American consumer, because the marginal cost of sending the extra units of the film to America is low. Nonetheless lower American revenue will force those films onto lower budgets. Possibly Canadian and also English movies will suffer the most, because they are most likely to have the U.S. as their dominant market.

Of course the U.S: is by far the world’s number one exporter of movies, so we are vulnerable to retaliation on this issue, to say the least.

Facts about robots

The robot is also just a fraction of the expense of integrating automation into a factory. A robot that stacks goods on to pallets can cost up to $150,000 to install when sensors, safety fencing, conveyors and other infrastructure are taken into account, according to Jorg Hendrikx, chief executives of robotics marketplace Qviro. Such costs put robotics out of the reach of many US manufacturers.

Just 20 per cent of factories with between 50 and 150 employees have a robot, half the rate of those with more than 1,000 staff, according to the US Census Bureau.

Sunday assorted links

1. Some underrated effects on AI on privacy-related issues.

2. How far are you from India, measured in units of India?

3. Roots of Progress blog-building fellowship.

4. Naipaul memories.

5. “Despite rising income inequality, intergenerational mobility remained largely stable in both countries.” [Sweden and the US]

6. Todd Kashdan makes the case for the “48 percent aligned.”

Not De Minimis

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick:

Ending the “de minimis loophole” is a big deal. This rule allowed foreign companies to avoid paying tariffs on small shipments, giving them an unfair advantage over American small businesses. To small businesses across the country: we have your back.

The Value of De Minimis Imports by Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal:

A U.S. consumer can import $800 worth of goods per day free of tariffs and administrative fees. Fueled by rising direct-to-consumer trade, these “de minimis” shipments have exploded in recent years, yet are not recorded in Census trade data. Who benefits from this type of trade, and what are the policy implications? We analyze international shipment data, including de minimis shipments, from three global carriers and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Lower-income zip codes are more likely to import de minimis shipments, particularly from China, which suggests that the tariff and administrative fee incidence in direct-to-consumer trade disproportionately benefits the poor. Theoretically, imposing tariffs above a threshold leads to terms-of-trade gains through bunching, even in a setting with complete pass-through of linear tariffs. Empirically, bunching pins down the demand elasticity for direct shipments. Eliminating §321 would reduce aggregate welfare by $10.9-$13.0 billion and disproportionately hurt lower-income and minority consumers.

In other words, eliminating the de minimis rule is a significant tax on poorer Americans.

Frankly, it’s also a pain in the ass to have your international shipments delayed at broker (who often charges you exorbitant rates, more than the customs tax) and then have to go down to the customs office to pay the stupid tax. Yes, I am speaking from experience.