Bailouts Forever

When interest rates rise, the price of long-term assets falls. Consequently, when the Fed began raising interest rates in 2022, the value of bonds and mortgages dropped, causing significant accounting losses for banks heavily invested in these assets. Silicon Valley Bank went bust, for example, because depositors fled upon realizing it was holding lots of Treasury bonds.

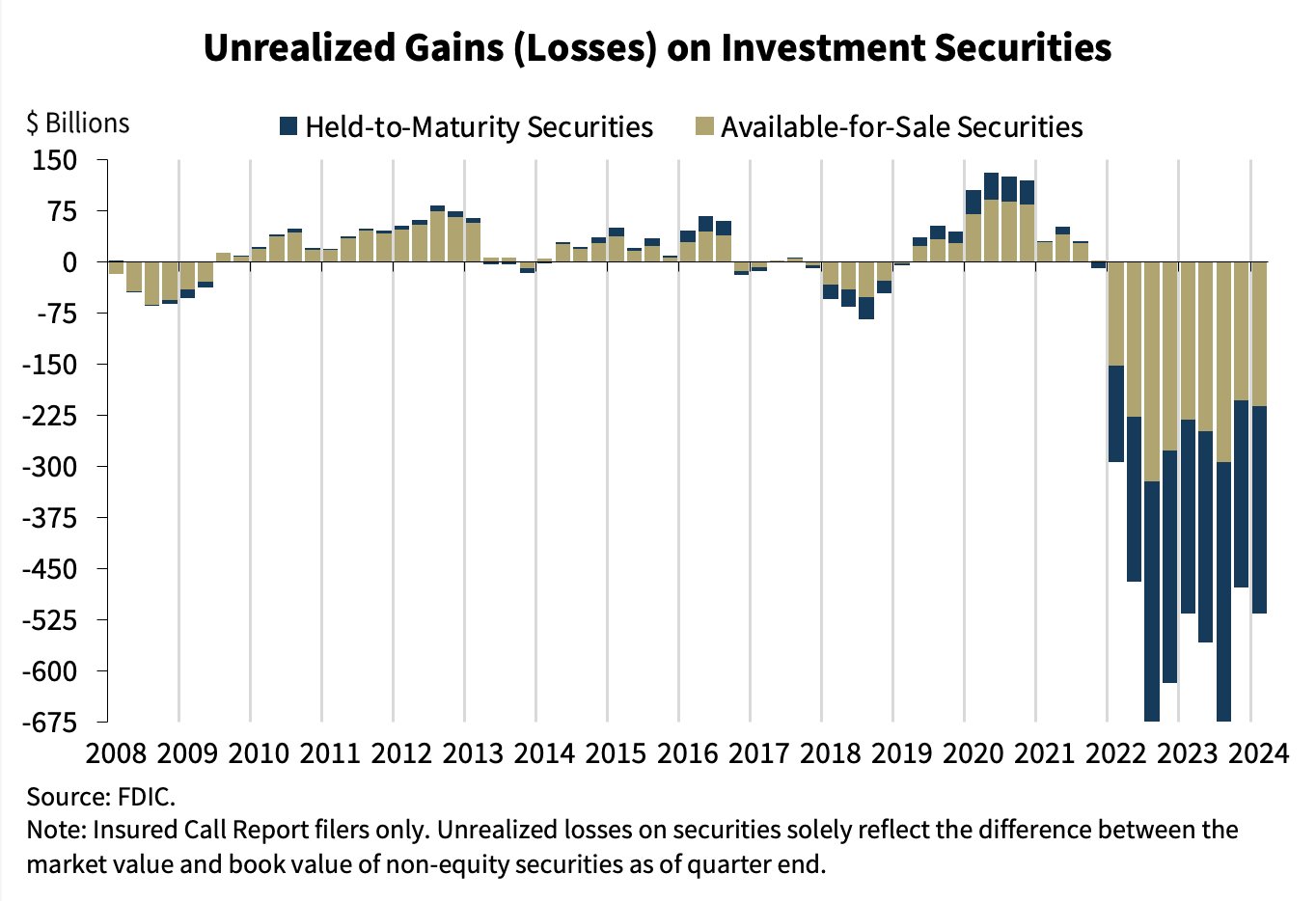

Interest rates remain high and many banks have large unrealized losses on their books. According to the latest FDIC data (see below) unrealized losses currently total $516.5 billion, far exceeding levels seen during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Price risk is not the same as default risk and if the banks can hold onto their assets until maturity then they will be solvent. The real danger, as with SVB, is if unrealized losses are combined with a deposit run. So far that doesn’t seem to be happening but it’s well within the realm of possibility.

In other news, Hypertext has an issue devoted to Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig’s The Banker’s New Clothes. Admati and Hellwig write:

The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act in the United States promised the end of bank bailouts and “too-big-to-fail” institutions. The European Union’s 2014 legislation for dealing with banks likely to fail was claimed to provide “a framework” to “deal with banks that experience financial difficulties without either using taxpayer money or endangering financial stability.” In November 2014, Mark Carney, at the time the governor of the Bank of England and chair of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), a body of financial regulators from around the world, announced triumphantly that an agreement about new rules for the thirty largest and most complex, “globally systemic” financial institutions would prevent bailouts in the future. Many people in politics and the media believed these claims.

Two From the Tabarrok Brothers

Maxwell Tabarrok offers an excellent review of an important paper.

Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century is a 2018 paper by Ufuk Akcigit, John Grigsby, Tom Nicholas, and Stefanie Stantcheva that provides some answers. They collect and clean new datasets on patenting, corporate and individual incomes, and state-level tax rates that extend back to the early 20th century. The headline result: taxes are a huge drag on innovation. A one percent increase in the marginal tax rate for 90th percentile income earners decreases the number of patents and inventors by 2%. The corporate tax rate is even more important, with a one percent increase causing 2.8% fewer patents and 2.3% fewer inventors.

Especially useful is Max’s back of the envelope calculation putting this result in the context of other methods to increases innovation.

Read the whole thing.

For something completely different, Connor Tabarrok offers an update on Charlotte the Stingray:

A “miracle pregnancy” picked up by national news brought huge business to a small-town aquarium, but months after the famous stingray was due, there are still no pups. Are we being scammed by a fish?

I particularly liked this line:

Taking all of this into account, my stance is that even if they got it on, it’s unlikely that this shark will have to dish out any child support to Charlotte’s pups.

Read the whole thing.

Are MR readers more interested in tax policy or virgin birth stingrays? We shall see.

Nationalism in Online Games During War

We investigate how international conflicts impact the behavior of hostile nationals in online games. Utilizing data from the largest online chess platform, where players can see their opponents’ country flags, we observed behavioral responses based on the opponents’ nationality. Specifically, there is a notable decrease in the share of games played against hostile nationals, indicating a reluctance to engage. Additionally, players show different strategic adjustments: they opt for safer opening moves and exhibit higher persistence in games, evidenced by longer game durations and fewer resignations. This study provides unique insights into the impact of geopolitical conflicts on strategic interactions in an online setting, offering contributions to further understanding human behavior during international conflicts.

That is from a new paper by Eren Bilen, Nino Doghonadze, Robizon Khubulashvili, and David Smerdon. Imagine if there is some addition Sino-Indian conflict right before the Ding vs. Gukesh WCC match…

For the pointer I thank various MR readers.

Why some additional regulation would help crypto

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one part of the argument, which focuses on the bill that recently passed the House but may stall in the Senate:

As for the policy details: Is this a good bill? Mostly, yes. Without a coherent regulatory framework, the US crypto sector won’t be competitive with those of other nations. That damages the potential for American innovation, encourages some entrepreneurs to take their businesses abroad, and could eventually limit the integration of crypto with mainstream financial infrastructures, which would put the US financial sector at a disadvantage.

The bill has the critical provision of requiring crypto infrastructures to be sufficiently decentralized, at least if that infrastructure is to fall under the jurisdiction of the CFTC rather than the SEC. These decentralized crypto infrastructures, which would include Bitcoin and the Ethereum network, are considered to be “digital commodities,” and are granted greater freedom. Such assets are not like shares of Apple stock, where the buyer expects a very particular kind of corporate responsibility and predictable financial reporting. So the bill stipulates that, for many crypto assets, initial issuance must involve tighter disclosure and regulation, with a role for the SEC. Over time, as the blockchain for that asset became more mature and well-established, regulation would relax.

Any particular proposal for such rules will necessarily involve some ambiguities and be susceptible to being gamed (by companies) or abused (by regulators). What is considered “adequate” decentralization, for example, is ultimately a subjective question. Still, this bill seems like a reasonable place to start for crypto regulation.

The alternative to such regulations of course is complete regulatory discretion, which is currently part of the status quo. And here is Alex’s recent post on crypto regulation.

The who and how of campaign spending on Meta

Trump targets horse riding, Biden targets football, and RFK Jr. targets comedy.

Trump also can claim Ted Nugent fans, here is the full story. Via A.

AI passes the restaurant review Turing test

Surprisingly easy, it turned out. In a series of experiments for a new study, Kovács found that a panel of human testers was unable to distinguish between reviews written by humans and those written by GPT-4, the LLM powering the latest iteration of ChatGPT. In fact, they were more confident about the authenticity of AI-written reviews than they were about human-written reviews.

Here is the full story, via Sarah Jenislawski.

Thursday assorted links

1. Alex Ross on Yuja Wang (New Yorker).

2. More on the South Korean gender gap.

3. Kyla Scanlon now has a book.

4. The San Francisco highway to NIMBYism.

5. Aristotle suggests a reverse Turing test (video). And Sam Hammond on the new California AI bill.

Money for Blood and Short Term Jobs

The excellent Tim Taylor on a new paper on plasma donation:

John M Dooley and Emily A Gallagher take a different approach in “Blood Money: Selling Plasma to Avoid High-Interest Loans” (Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming, published online May2, 2024; SSRN working paper version here). They are investigating how the opening of a blood plasma center in an area affects the finances of low-income individuals. As background, they write:

“Plasma, a component of blood, is a key ingredient in medications that treat millions of people for immune disorders and other illnesses. At over $26 billion in annual value in 2021, plasma represents the largest market for human materials. The U.S. provides 70% of the global plasma supply, putting blood products consistently in the country’s top ten export categories. The U.S. produces this level of plasma because, unlike most other countries, the U.S. allows pharmaceutical corporations to compensate donors – typically about $50 per donation for new donors, with rates reaching $200 per donation during severe shortages. The U.S. also permits comparatively high donation frequencies: up to twice per week (or 104 times per year)…”

Not too surprisingly, plasma donors tend to be young and poor and they use plasma donation to substitute away from non-bank credit like payday loans.

I am struck by Tim’s thoughts on how this connects with labor markets and regulation:

…I find myself thinking about the financial stresses that many Americans face. Being paid a few hundred dollars for a series of plasma donations isn’t an ideal answer. Neither is taking out a high-interest short-term loan; indeed, taking out a loan at all may be a poor idea if you aren’t expecting to have the income to pay it back. In the modern US economy, hiring someone for even a short-term job involves human resources departments, paperwork, personal identification, bookkeeping, and tax records. These rules have their reasons, but the result is that finding a short-term job that pays for a few days work isn’t simple, even if though most urban areas have a semi-underground network of such jobs.

Roger Miller’s classic 1964 song, “King of the Road,” tells us that “two hours of pushin’ broom/ Buys an eight by twelve four-bit room.” Even after allowing for a certain romancing of the life of a hobo in that song, the notion that a low-income person can walk out the door and find an two-hour job that pays enough to solve immediate cash-flow problems–other than donating plasma–seems nearly impossible in the modern economy.

My Conversation with the excellent Michael Nielsen

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Michael Nielsen is scientist who helped pioneer quantum computing and the modern open science movement. He’s worked at Y Combinator, co-authored on scientific progress with Patrick Collison, and is a prolific writer, reader, commentator, and mentor.

He joined Tyler to discuss why the universe is so beautiful to human eyes (but not ears), how to find good collaborators, the influence of Simone Weil, where Olaf Stapledon’s understand of the social word went wrong, potential applications of quantum computing, the (rising) status of linear algebra, what makes for physicists who age well, finding young mentors, why some scientific fields have pre-print platforms and others don’t, how so many crummy journals survive, the threat of cheap nukes, the many unknowns of Mars colonization, techniques for paying closer attention, what you learn when visiting the USS Midway, why he changed his mind about Emergent Ventures, why he didn’t join OpenAI in 2015, what he’ll learn next, and more.

And here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Now, you’ve written that in the first half of your life, you typically were the youngest person in your circle and that in the second half of your life, which is probably now, you’re typically the eldest person in your circle. How would you model that as a claim about you?

NIELSEN: I hope I’m in the first 5 percent of my life, but it’s sadly unlikely.

COWEN: Let’s say you’re 50 now, and you live to 100, which is plausible —

NIELSEN: Which is plausible.

COWEN: — and you would now be in the second half of your life.

NIELSEN: Yes. I can give shallow reasons. I can’t give good reasons. The good reason in the first half was, so much of the work I was doing was kind of new fields of science, and those tend to be dominated essentially, for almost sunk-cost reasons — people who don’t have any sunk costs tend to be younger. They go into these fields. These early days of quantum computing, early days of open science — they were dominated by people in their 20s. Then they’d go off and become faculty members. They’d be the youngest person on the faculty.

Now, maybe it’s just because I found San Francisco, and it’s such an interesting cultural institution or achievement of civilization. We’ve got this amplifier for 25-year-olds that lets them make dreams in the world. That’s, for me, anyway, for a person with my personality, very attractive for many of the same reasons.

COWEN: Let’s say you had a theory of your collaborators, and other than, yes, they’re smart; they work hard; but trying to pin down in as few dimensions as possible, who’s likely to become a collaborator of yours after taking into account the obvious? What’s your theory of your own collaborators?

NIELSEN: They’re all extremely open to experience. They’re all extremely curious. They’re all extremely parasocial. They’re all extremely ambitious. They’re all extremely imaginative.

Self-recommending throughout.

The Milei speech at Hoover (in Spanish)

I haven’t listened yet, but I am told he goes through an exegesis of Coase on the lighthouse…

Here is a Jon Hartley summary, he also talks about the Lakers and the Celtics.

New Malcolm Gladwell book

Wednesday assorted links

1. Rave review for Richard Flanagan’s Question.

2. Longer novels are more likely to win literary awards.

3. Typing Chinese on a QWERTY keyboard.

4. “ChatGPT is used most frequently in India, China, Kenya and Pakistan, with 75%, 73%, 69% and 62% of respondents, respectively, reporting using ChatGPT daily or weekly” Link here.

5. Mark Koyama on Geoffrey Hodgson.

6. William Shoki on South Africa (NYT). And Jeffrey Paller on the South African elections.

Monaco on the Marin Headlands

The Dalmation Coast in Croatia, the Amalfi Coast in Italy and Monaco’s coast on the Mediterranean Sea are often found on lists of the most beautiful coastlines in the world. Here are some pictures. Hard not to agree. The fourth picture is of the Marin coastline near San Francisco. It’s also beautiful but is it obviously more beautiful than the other coastlines? Personally, I don’t think so. But one thing is different. Far fewer people are enjoying the Marin coast. Why? Because fewer people live there. Can something be beautiful if there is no one to see it?

There is something to be said for protecting natural wilderness but must we do so on some of the most valuable land in the world?

I agree with Market Urbanism, “Quite simply, we must build Monaco on the Marin Headlands.”

Hat tip to Bryan Caplan who makes the point about beauty in his excellent, Build, Baby, Build.

Croatia

Amalfi

Monaco

Marin:

What film or literature is useful for making sense of the AI moment?

That is a reader query, I take it there is no point in my trotting through the obvious picks, starting with I, Robot and Her. Sophisticates will ponder Stanislaw Lem’s Cyberiad, which very well understood the quirky and semi-religious potential in LLMs, even though he was writing in Communist Poland a very long time ago (those people loved to talk about cybernetics).

Have you ever pondered the 1994 Sandra Bullock movie Speed? I think at this point it is not a spoiler to report “It revolves around a bus that is rigged by an extortionist to explode if its speed falls below 50 miles per hour.” And yes, this is a Hollywood movie of the 1990s, so it does end in a kiss.

Here is a visual mapping of how science fiction has made sense of AI. Am I neglecting any other non-obvious picks?

Urban design taken seriously?

Why does “how would you design a city so that more people fall in love?” feel like an absurd question? It shouldn’t be https://t.co/Z2GfCYEOjo

— Tyler Alterman (@TylerAlterman) April 28, 2024

GPT-4o suggested:

“1. **Serendipity Corners**:

– Implement areas designed to encourage unexpected encounters. For example, interactive art installations or quirky features can serve as conversation starters. These could change frequently to keep the city dynamic, such as rotating sculptures or murals with interactive elements like touch-activated sound…

3. **Social Puzzles**:

– Install public games or puzzles that require collaboration from multiple people. This could be anything from giant chess boards to augmented reality treasure hunts that encourage teams to work together to solve clues scattered throughout the city.”

Claude’s answers were along broadly similar lines. For an economic answer, how about “raise the city income tax on working”? Love is not taxed, but work income is. Furthermore, these days it is relatively difficult to strike up romantic relationships in many kinds of workplaces. (Of course you would need offseting “stay in the city” subsidies, in balanced budget fashion.) Taxing female education is another bad idea, but if the unconstrained goal is to increase the number of love matches that might work too.

What else?