Month: January 2014

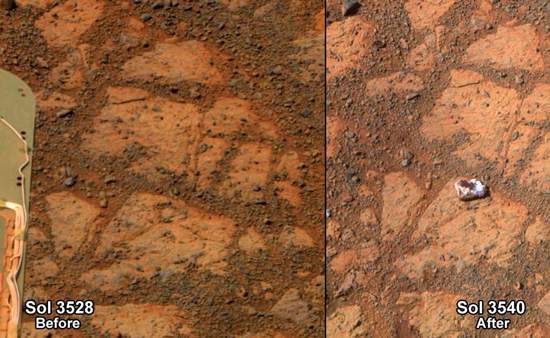

Please explain this new white rock to me, #Mars, #SmallSteps

The link is here, and for the pointer I thank Gordon. At least it’s not a watch.

Do High Interest Rates Defend Currencies During Speculative Attacks?

That is the question posed by a paper (pdf) by Aart Kraay of the World Bank, written in 2001 and focusing mainly on fixed exchange rate scenarios. It seems the high rates do not protect currency values, here is the abstract:

Do high interest rates defend currencies during speculative attacks? Or do they have the perverse effect of increasing the probability of a devaluation of the currency under attack? Drawing on evidence from a large sample of speculative attacks in developed and developing economies, this paper argues that the answer to both questions is ”no”. In particular, this paper documents a striking lack of any systematic association whatsoever between interest rates and the outcome of speculative attacks. The lack of clear empirical evidence on the effects of high interest rates during speculative attacks mirrors the theoretical ambiguities on this issue.

This study (jstor) from the JPE, by Lahiri and Vegh, shows mixed results and also explains why the higher interest rates may be counterproductive. They increase public debt service and may predict higher future inflation, thereby worsening some of the constraints and possibly hastening a further speculative attack.

Here is an Allan Drazen survey on raising interest rates to defend a currency (pdf), much of which focuses on the signaling effect. He argues the non-signaling effects are generally weak and when it comes to the signaling effects it can cut either way. Needing a large rate hike to defend a currency is in some ways a negative signal as well. The empirics are discussed starting on p.51 and one result seems to be short-term benefits and medium-term deterioration, following a big interest rate hike to protect a currency. Again, you will note this estimation is drawn from a lot of fixed rate countries and it may apply to floating rate scenarios only with qualifications.

You will find other relevant readings here.

The big news, of course, is that the Turkish central bank yesterday announced a 425bp rate hike, to stem a currency crisis. There is FT Alphaville on the move here, more readings here. The markets seem to like this move, at least at first, but based on what we know from the literature, we should not be too quick to think this will succeed.

Markets in everything

For only 23,500 euros (who says you can’t take it with you?):

Sweden’s Catacombo Sound System is a funeral casket that eternally plays the deceased’s choice of tracks while they’re six feet under.

Created by Pause Ljud & Bild, the system consists of three different parts. Firstly, users create an account through the online CataPlay platform, which connects to Spotify and enables customers to curate a playlist for their own coffin or get friends and family to choose the tracks when they’re gone. The CataTomb is a 4G-enabled gravestone that receives the music from CataPlay and display the current track — along with details and tributes to the deceased — through a 7-inch LCD Display. Finally, the CataCoffin is where the parted will themselves enjoy two-way front speakers, 4-inch midbass drivers and an 8-inch sub-bass element that deliver dimensional high-fidelity audio tailored to the acoustics of the casket. The video below explains more about the concept…

Of course I want Brahms’s German Requiem, the Rudolf Kempe recording. I am afraid, however, that I (in some form) will last longer than Spotify does.

For the pointer I thank Michael Rosenwald.

Assorted links

1. Ike Brannon reviews Average is Over. And Acemoglu, Autor, et.al. consider whether the IT revolution is really so strong in the numbers.

2. I’ve been arguing for a while that the GOP has no real intention of repealing Obamacare. Patrick Brennan summarizes the new GOP plan. Brad DeLong adds comment.

3. Pete Seeger doing “Rock Island Line. And on banjo, “Little Birdie.” An obituary is here. “Wimoweh” is here.

4. State-level regulations are coming for Bitcoin.

5. Vision care insurer will cover Google Glass. Related information is here.

Why the Worst Get on Top – India Edition

Consider this extraordinary figure: 30 percent of members of parliament have criminal cases pending against them…the answer to why political parties in India nominate candidates with criminal backgrounds is painfully obvious: because they win (see figure 1). In the 2004 or the 2009 parliamentary elections, a candidate with no criminal cases pending had—on average—a 7 percent chance of winning. Compare this with a candidate facing a criminal charge: he or she had a 22 percent chance of winning. Granted, this simple comparison does not take into account numerous other factors such as education, party, or type of electoral constituency. Nevertheless, the contrast is marked.

Writing at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace blog, Milan Vaishnav goes on to note that those with criminal backgrounds appear to have ready access to cash and in addition their toughness appeals to voters:

In contexts where the rule of law is weak and social divisions are highly salient, politicians often use their criminal reputation as a badge of honor—a signal of their credibility to protect the interests of their parochial community and its allies, from physical safety to access to government benefits and social insurance.

…The appeal of candidates who are willing to do what it takes—by hook or crook—to protect the interests of their community provides some intuition for why the odds of a parliamentary candidate winning an election actually increase with the severity of the charges, with slightly diminishing returns in the most severe instances…

How average is perceived as being over

If you actually take a close look at the numbers, it turns out that of the people who identified as middle class in 2008, nearly a third of them now identify as lower middle or lower class.1 This is even more dramatic than it seems. Class self-identification is deeply tied up with culture, not just income, and this drop means that a lot of people—about one in six Americans—now think of themselves as not just suffering an income drop, but suffering an income drop they consider permanent. Permanent enough that they now live in a different neighborhood, associate with different friends, and apparently consider themselves part of a different culture than they did just six years ago.

There is more here, from Kevin Drum.

Does Medical Malpractice Law Improve Health Care Quality?

Maybe not so much. That is a new paper by Michael Frakes and Anupam B. Jena, the abstract is here:

Despite the fundamental role of deterrence in justifying a system of medical malpractice law, surprisingly little evidence has been put forth to date bearing on the relationship between medical liability forces on the one hand and medical errors and health care quality on the other. In this paper, we estimate this relationship using clinically validated measures of health care treatment quality constructed with data from the 1979 to 2005 National Hospital Discharge Surveys and the 1987 to 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System records. Drawing upon traditional, remedy-centric tort reforms—e.g., damage caps—we estimate that the current liability system plays at most a modest role in inducing higher levels of health care quality. We contend that this limited independent role for medical liability may be a reflection upon the structural nature of the present system of liability rules, which largely hold physicians to standards determined according to industry customs. We find evidence suggesting, however, that physician practices may respond more significantly upon a substantive alteration of this system altogether—i.e., upon a change in the clinical standards to which physicians are held in the first instance. The literature to date has largely failed to appreciate the substantive nature of liability rules and may thus be drawing limited inferences based solely on our experiences to date with damage-caps and related reforms.

There is an ungated version of the paper here.

Assorted links

1. More Pentagon chatter about robots. And man-machine co-authored sonnet. Video about robots who attend weddings.

2. Should we allow state-based visas? I wrote back to Adam Ozimek: “thanks, I will link to this, suppose I don’t yet have an original comment as to whether the more immigrants vs. potential balkanization trade-off is worth it…”

3. What characterizes the 2013-2014 job market stars in economics?

4. Economic development and the dangers of stories.

5. The business model behind Vox. And are the best things in life W.E.I.R.D.?

Assortative mating and income inequality

Jeremy Greenwood, Nezih Guner, Georgi Kocharkov and Cezar Santos have a new NBER Working Paper, the abstract is this:

Has there been an increase in positive assortative mating? Does assortative mating contribute to household income inequality? Data from the United States Census Bureau suggests there has been a rise in assortative mating. Additionally, assortative mating affects household income inequality. In particular, if matching in 2005 between husbands and wives had been random, instead of the pattern observed in the data, then the Gini coefficient would have fallen from the observed 0.43 to 0.34, so that income inequality would be smaller. Thus, assortative mating is important for income inequality. The high level of married female labor-force participation in 2005 is important for this result.

That is quite a significant effect. There are ungated versions of the paper here. Here is a related post by Alex.

Addendum: Kevin Drum offers additional comment.

Wealth and PISA scores: why doesn’t money help U.S. performance more?

The data was provided to The WorldPost by Pablo Zoido, an analyst at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the group behind PISA. It shows that students’ wealth does not necessarily make them more competitive on an international scale. In the United States, for example, the poorest kids scored around a 433 out of 700 on the math portion of PISA, while the wealthiest ones netted about a 547. The lower score comes in just below the OECD average for the bottom decile (436), but the higher score also comes in below the OECD average for the top decile (554).

“At the top of the distribution, our performance is surprisingly bad given our top decile is among the wealthiest in the world,” said Morgan Polikoff, a professor at the University of Southern California’s School of Education who reviewed the data.

The data also makes for some jarring comparisons: Canada’s fourth decile performs as well as Chile’s top socioeconomic tier. Taiwan’s bottom sliver performs about as well as Montenegro’s wealthiest 10 percent. Vietnam’s bottom 10 percent slightly eclipses Peru’s top 10 percent. And the poorest kids in Poland perform about on par with Americans in the fourth decile.

The article is by Diehm and Resmovitz, pictures at the link, hat tip goes to @ModeledBehavior. One possible implication is that the so-so U.S. performance on these tests is about culture in a way that just doesn’t reduce to poverty for the lower deciles.

Are recessions a good time to boost the minimum wage?

One empirical regularity is that many minimum wage boosts come during recessions or downturns, as many of you pointed out here. Yet I take this repeated pattern to be an argument for having a low, zero, or quite “fettered” minimum wage.

Let’s think through the economics. One of the main pro-minimum wage arguments — arguably the #1 argument — cites labor market monopsony. Let’s say you have a monopsonistic employer who holds back on bidding for more labor, out of fear that hiring more labor raises the price paid on all labor units of a certain quality (by assumption, there is no perfect price discrimination here). The minimum wage can get you out of this trap. By forcing the higher wage on all workers in any case, the employer now doesn’t hesitate to hire more of them because the “fear of bidding up the price of labor” effect is gone or diminished. And that is how, in some situations, a higher minimum wage can boost employment.

Now let’s say the economy is in a demand-driven downturn, which creates a surplus in the labor market. Now, to get more workers, the monopsonist firm does not have to raise the wage and it can get more workers at the prevailing wage. But employers just don’t want more workers, because of demand-side constraints. So employers could in fact hire more workers without pushing up wage rates at all, once again that is for all units of labor of a particular quality. Yes there is still monopsony, but the potential wage effects of hiring more labor are muted by the labor surplus. And that means boosting the minimum wage won’t create the beneficial hiring effects which operate in the more traditional monopsony scenario, explained in the paragraph directly above.

In other words, if you think we are now seeing a slow labor market for demand-side reasons, you should be skeptical of the monopsony argument for minimum wage hikes, at least for the time being.

By the way, demand-side problems often wreck the notion that the EITC and minimum wage are complements.

The bottom line is that a lot of the arguments for a higher minimum wage are inconsistent with or in tension with a demand-driven labor market slowdown. And I don’t exactly see the world rushing to point this out.

Here is my earlier argument that slow labor markets are the worst times to boost minimum wages. Here is my earlier post drawing a parallel between minimum wages (government-enforced sticky wages) and privately-enforced sticky wages. Here is an excerpt from that post:

I know many economists who will argue: “let’s raise the state-imposed minimum wage. Employers will respond by creating higher-productivity jobs, or by paying more, and few jobs will be lost.” I do not know many Keynesians who will argue: “In light of the worker-imposed minimum wage, employers will respond by creating higher-productivity jobs, or by paying more, and few jobs will be lost.”

Addendum: By the way, here are some graphs and regressions about the minimum wage and recessions, from Kevin Erdmann. I think he is attempting the impossible, but you still might find it instructive to look at some of the pictures.

The new Ezra Klein venture at Vox

You can find Ezra’s words here. Do read the whole thing, here is one excerpt:

Today, we are better than ever at telling people what’s happening, but not nearly good enough at giving them the crucial contextual information necessary to understand what’s happened. We treat the emphasis on the newness of information as an important virtue rather than a painful compromise.

The news business, however, is just a subset of the informing-our-audience business — and that’s the business we aim to be in. Our mission is to create a site that’s as good at explaining the world as it is at reporting on it.

Matt Yglesias, Dylan Matthews, and Melissa Bell (and others to follow) will be coming along. Here is David Carr on the venture.

Addendum: The jobs ad is quite useful:

Project X (working title) is a user’s guide to the news produced by the beat reporters and subject area experts who know it best.

We’ll have regular coverage of everything from tax policy to True Detective, but instead of letting that reporting gather dust in an archive, we’ll use it to build and continuously update a comprehensive set of explainers of the topics we cover. We want to create the single best resources for news consumers anywhere.

We’ll need writers who are obsessively knowledgeable about their subjects to do that reporting and write those explainers — as well as ambitious feature pieces. We’ll need D3 hackers and other data viz geniuses who can explain the news in ways words can’t. We’ll need video producers who can make a two-minute cartoon that summarizes the Volcker rule perfectly. We’ll need coders and designers who can build the world’s first hybrid news site/encyclopedia. And we’ll need people who want to join Vox’s great creative team because they believe in making ads so beautiful that our readers actually come back for them too.

Sound like you? Then apply now.

And Ezra explains more here.

Meeting one’s higher calling?

From Madurai, Robyn Eckhardt reports:

Onion, cauliflower, fenugreek, garlic, egg white, potato, mushroom and masala are just some of the variations on dosa offered by the 49-year-old Mr. Karthikeyan, who took over the business from his father after earning a master’s degree in economics. “What could I do? There was no one else,” he explained as he unhurriedly worked five griddles simultaneously — four for dosai and one for fried dishes like masala powder-seasoned hard-boiled eggs with onion, cilantro and curry leaves. “Back then, a dosai cost a quarter of a rupee,” he said. Today Ayyappan charges 10 rupees and up.

There is more here, via these sources.

Assorted links

Economic data on hitmen

The sample is pretty limited, but here is what they find:

The killers typically murder their targets on a street close to the victim’s home, although a significant proportion get cold feet or bungle the job, according to criminologists who examined 27 cases of contract killing between 1974 and 2013 committed by 36 men (including accomplices) and one woman.

…The reality of contract killing in Britain tended to be striking only in its mundanity, according to David Wilson, the university’s professor of criminology. He said: “Far from the media portrayal of hits being conducted inside smoky rooms, frequented by members of an organised crime gang, British hits were more usually carried out in the open, on pavements, sometimes as the target was out walking their dog, or going shopping, with passersby watching on in horror.”

Researchers found that the average cost of a hit was £15,180, with £100,000 being the highest and £200 the lowest amount paid. The average age of a hitman was 38 with the youngest aged 15 and the oldest 63.

The youngest, Santre Sanchez Gayle from north London, shot dead a young woman at point-blank range with a sawn-off shotgun in 2010 after she answered her front door. The oldest was David Harrison who, also in 2010, shot the owner of a skip-hire business in his Staffordshire home.

Most hits involved a gun, with three victims stabbed, five beaten to death and two strangled. The most conspicuous weapon was used in the killing of David King, a widely feared underworld figure known as “Rolex Dave”, who in 2003 was shot five times as he emerged from a Hertfordshire gym by hitman Roger Vincent and his accomplice David Smith, both 33. The killing was the first time an AK-47 assault rifle – apparently belonging to the Hungarian prison service – had been used on a British street.

For the pointer I thank Mike Brown. By the way, those records are focused on Birmingham, England, which perhaps is not like Lodi, New Jersey in this regard.

The original work is cited as appearing in the Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, but I do not seem to find the article at that link.